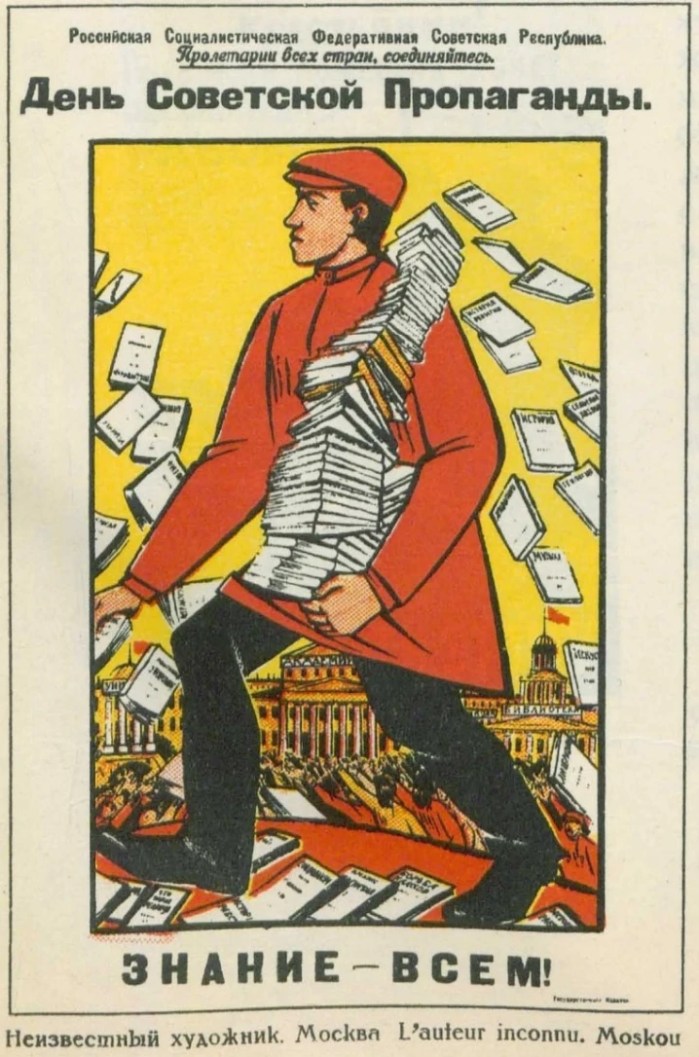

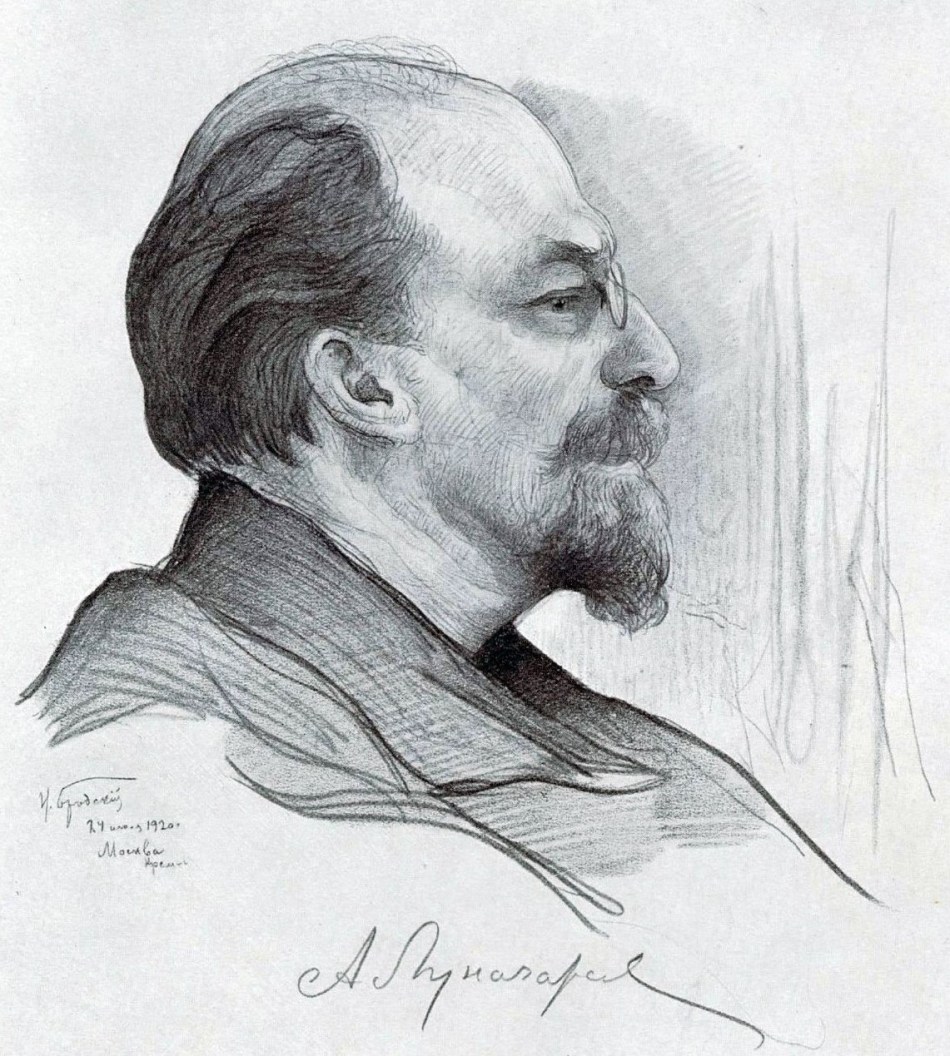

The first of two in-depth article on art in Soviet Russia by French anarchist art historian Jacques Mesnil looks at how works from the Ancien Régime was viewed, appropriated, and safeguarded by the new Soviets under the direction of Anatoly Lunacharsky.

‘Art Under the Proletariat’ by Jacques Mesnil from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 6 No. 5. May 1, 1922.

(The distinguished French critic takes up in this article the preservation of past beauty; an article from his pen in the next issue will take up the future of art in Russia.)

IN speaking of art in present day Russia one must guard against a failing common to many of the advocates and opponents of the Soviet system, a state of mind altogether too common to-day, as in all moments of great convulsion: the tendency to expect miraculous things, the belief in marvels, not as it was held in the middle ages, in a juvenile form, in its direct material aspect, but, in accordance with the character of our knowing age—at least such the age considers itself to be—in a more abstract, more spiritual, more symbolic form. To-day, people believe in the possibility of radical and sudden transformations in the psychology of an entire nation, in the instantaneous creation, by the mere fact of revolution, of an artistic renaissance, in the spontaneous generation of works of art bursting from a socially convulsing soil. And this state of mind is characteristic both of the defenders and adversaries of the regime that issues from the Russian Revolution. Some time ago I read in Le Flambeau, a magazine appearing in Belgium, a long article by Boris Sokolov, a well-known anti-Bolshevik, who made use of the absence of a great rebirth of artistic creation in Russia since the November Revolution in order to blacken the regime which resulted from the Revolution and to prove its sterility from the standpoint of general culture. To speak in this fashion is to show that one has no historical knowledge whatsoever, that one has never reflected on the past: I do not know of any great artistic awakening which was contemporary with a violent movement of social transformation. Not to go too far afield in our search for examples, let us ask whether the French Revolution immediately produced anything really new or powerful in art, comparable with the great social convulsion brought about by the Revolution? It did not. People then admired classic art, the revival of the Greeks and Romans; not only their form, but even their subjects and myths were imitated and adapted more or less to the ideas of the day: Republican faiences were manufactured, of no greater or less artistic value than most of the propaganda posters put out to-day.

The great change in literature and in art was not to come about until thirty years later, and was destined to be the work of the new generation, born after the Revolution, who had breathed its air and absorbed its dominant ideas from childhood, who had grown up in the midst of the immediate memories of its heroic struggles and in the atmosphere of the great events that followed upon it: in France it is the Romantic movement which represents the revolution in art. And the forces released by the revolution find their artistic expression in this movement; when they ceased actively to influence the masses and to bring about new uprisings, in this moment of calm these forces developed all their dynamic power in the domain of the spirit.

Consider also other great social transformations, such as the formation of Communes in the middle ages, and you will find that there also the blossoming of art follows at a certain distance upon the political events, and that they continued far beyond the culmination of the economic development.

Particularly when we consider a Communist society, as was the Commune of the middle ages, and as will be the society toward which the Russian revolution is working, there is a further material cause preventing the immediate blossoming of a new art; this is the fact that in any Communist society the predominant art is necessarily architecture, which is the immediate and direct response to the common life, while sculpture and painting are as it were the adornments of architecture, calculated to complete the total impression. And the great works of architecture cannot be created except in periods of comparative calm, when the wealth of the community is large enough and the labor forces numerous enough to make the erection of buildings possible.

My task will therefore be limited by the very nature of the case, and when I start out to speak of the present day art in Soviet Russia I shall be obliged to consider particularly the two modes of action that are now possible; the preservation of the monuments of existing art, and the effort to educate, to prepare for the creation of new works; preservation of the past and preparation for the future, these two ideas fully embrace the tasks now facing the guiding spirits of the Russian Revolution. I shall take up these two points in order.

I.

When you travel in Russia you are struck by the fact that the Revolution has destroyed so little, even in the places where it was most active; there are the traces of machine gun bullets on the facades of public structures and even on houses that served as shelters for one hostile faction ог the other; some houses were burned down, very few of them to be sure, much fewer than the houses that deteriorate and go to pieces because of the economic poverty of the country, blockaded and unable to make the necessary repairs, even such as are indispensable in the case of a city built on marshy soil, as is Petrograd.

But nowhere is there anything comparable to the destruction produced by the war, anything that would even remotely resemble Reims or Arras.

The only city in which art monuments have been seriously damaged is Yaroslav, and here we are dealing not with the work of the revolution, but with that of counter-revolutionists in the pay of the Entente Governments, whose official representatives had leisure to carry on their plots under the cover of diplomatic immunity, ready to starve the Russian people, in the hope of overthrowing the Soviet Government, as clearly appears from the facts as reported by René Marchand.

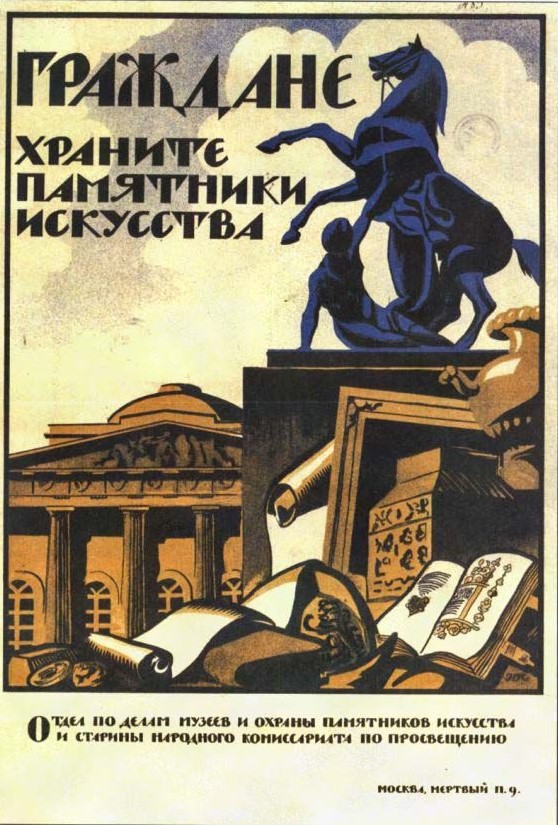

The iconoclastic tendencies observable in the French Revolution are not to be found in the Russian Revolution: there is nothing here resembling the destruction of statues representing personages of the Old Testament, in the galleries of Notre-Dame-de-Paris, which were destroyed because they were taken for statues of the kings of France. To be sure, emblems of the tsarist regime have been torn down in certain places, but Lunacharsky, People’s Commissar for Public Instruction, has succeeded in having all those objects spared which had any historic or artistic value, and the double eagles of the Russian Empire are still perched over the Kremlin.

Certain modern statues of Russian generals that were particularly hated as representatives of the tsarist régime of oppression of the people have been destroyed, but none of them was of any real artistic value. The painted and carved effigies of the former rulers were saved wherever they had any esthetic value, and the losses in this field are insignificant.

Even the opponents of the Government recognize this fact. You should read in this connection the curious book of Polovtsev: Art Treasures in Russia under the Bolshevist Regime. The author is a savage opponent of the Bolsheviki, as is proved by that sentence in his book in which he resents the excellent good taste displayed by Lunacharsky. Polovtsev, visiting the old imperial palace at Pavlovsk, cries out: “I could never understand how a man of such fine discrimination and such highly developed esthetic culture could voluntarily become a member of this gang of savage orangoutangs who had seized the power and were abusing it in order to destroy everything that makes life tolerable.” Polovtsev was in Russia for about a year after the Revolution of November, 1917, and he was engaged chiefly in guarding the imperial palaces in the neighborhood of Petrograd, particularly at Pavlovsk. His testimony is onesided but not dishonest. From the facts which he himself observed, and which he recounts with precision, it is clear that he always received the assistance he asked from the authorities, and that his petitions to the Bolsheviki, superiors as well as assistants, were always finally granted, “They fully understood,” the author himself writes, “that my work was based on an abstract idea, and they always yielded to this idea.” Would he have found under other systems of government so many superior and subaltern officials who were inclined to yield to an abstract idea? I doubt it.

The old palaces and Summer residences of the tsars in the neighborhood of Petrograd have therefore not only not been destroyed or pillaged, but much encouragement has been given to the work of cataloguing their furnishings and collections, and the palaces have been turned into museums, open to the public since June, 1918. Before we take leave of Mr. Polovtsev, let us borrow from him also an account of the impressions he received from these first visits, which are so indicative of the serious and reflective character of the Russian people (pages 273-274):

“In June, 1918, we opened to the public the palaces of Tsarskoye Selo, Pavlovsk, Gatchina and Peterhof, two or three days each week, and there were immense crowds to visit them. At Tsarskoye more than eight thousand persons came on Sunday and, in order to save the floors, Lukovsky had slippers made out of some old matting which would fit over any size of shoe. We were afraid that the soldiers would never consent to put on these slippers, but we were mistaken. Once, when a man refused to put them on, all those who were grouped around the guide declared that they would not enter the museum until this person had submitted to the rules. At Pavlovsk, I had broken in a certain number of guides, but as they were sometimes overworked, I used to help them on holidays. We had to remind the public that they must not touch objects or furnishings, but if there were аny infractions they were due only to oversight, and I have never met with a single case of intentional vandalism. In all the Summer there was only one case when a visitor had to be expelled from any of these palaces, and although we often heard such exclamations as: ‘That’s the way they lived,’ or: ‘I can see that their life must have been pretty soft in halls like these!’ I was especially struck by the number of intelligent questions that were addressed to me and the desire to learn shown by many persons. Teachers’ Congresses, Art History courses, organizations of all kinds, arrange excursions to these palaces; but we always prepared in advance to receive these floods of visitors, and I have often been much touched by letters from persons whose names I have forgotten, who asked me for some information, and who referred to the explanations I had given them in the apartments at Pavlovsk.” Another characteristic which distinguishes the Russian Revolution from the French Revolution and which has aided in preserving works of art is the absence of any strong anti-religious current; the Revolutionists showed themselves to be quite tolerant toward the clergy: the churches remain open and have retained all the ostentatious splendor that is characteristic of the orthodox worship: the priests continue to display their rich trumpery, and not only the works of art but also objects of worship which are precious only for their materials are preserved in a nation which could make excellent use of these materials in barter with foreign countries.

Another cause for astonishment in my eyes was to find the personnel of the museums almost unchanged. After reading the newspapers in Western Europe, I had imagined that all the intellectuals, the whole “Intelligentsia,” had been exiled or had refused to cooperate with the new system. As far as the custodians of art museums and art objects are concerned, this is entirely untrue: the first historian of Russian art, the painter Igor Grabar, is stationed at the Tretyakov Museum, devoted to Russian painting in Moscow, and has charge of the whole museum; the staff of the Ermitage Museum at Petrograd is almost intact. “The Master of the Ceremonies,” Count Tolstoy, who managed this museum under Tsarism, has fortunately been replaced by the custodian of the section of Ceramics and Goldsmith Work, the young and energetic Troinitsky, who continues to devote immense energy to the conservation, increase, and reorganization of this museum, one of the finest in the world; the Ermitage also has obtained an excellent addition to its forces in the person of the painter Alexandre Benois, who is very well known in Russia, the founder of the society Mir Iskusstva (The World of Art), who had an exposition this Summer in Paris and who also had some pictures in the Autumn Salon. Alexandre Benois, who had always been unrecognized under the tsarist régime, has become the chief custodian of the section of painting. Count Zubov, who founded an Institute for the History of Art in 1911, remains at the head of his “Socialist” Institute. I have spoken to all these scholars and have had an opportunity to converse with them at length. I spent a day with Zubov at Pavlovsk in the Palace and in the splendid park of which Polovtsev speaks at such length; I visited the gallery of the Ermitage several times, accompanied by its custodians. I may therefore speak with full knowledge of the condition of these museums, of the changes through which they have passed in these latter years, of their present organization, and of the circumstances of the custodians.

From Petrograd, when it was exposed to an attack from the sea, when Russia was still at war with Germany, a portion of the Ermitage collections were evacuated, particularly the precious objects and a great number of the Southern Russian antiquities. Under the Kerensky régime, it was decided to transfer all the rest to Moscow. In September and October, 1917, two trains, bearing more than 800 cases, were dispatched from Petrograd. A third consignment was to complete the transfer, but did not take place because of the Bolshevik Revolution, which came at just that time.

There remained at the Ermitage only the ancient sculptures, and almost all the modern sculptures, the prints, and the glasses.

At Moscow, where the cases were piled in the Kremlin and in the Historical Museum on the Red Square, contiguous with the Kremlin, these masterpieces were exposed to great danger during the November Revolution, in the midst of street fights and bombardments that were concentrated precisely on these points, but fortunately nothing was damaged.

Plan to Divide Up Collections

Later, the Ermitage collections, in their Moscow shelter, were exposed to another risk: that of being divided among various Russian cities; in certain circles, which had great influence on the Commission for Museums and Monuments, attached to the Commissariat of Public Instruction, the idea of decentralization was very strong, with the object of creating a great number of centers of culture. It was pointed out, not without reason, that the predominance granted to Petrograd as an intellectual center was quite artificial. Created at the whim of an autocrat who doted on Western civilization, this city had usurped the place of Moscow, the ancient capital, and the tsars who succeeded Peter the Great had made every effort to accumulate at Petrograd all the art treasures which they were able to purchase with the wealth produced by the exploitation of the people. But in 1905, Petograd had revealed itself as a revolutionary city; it had been abandoned by the Court, which no longer felt secure in this city, becoming more and more modern, and where the industrial element was beginning to acquire immense importance, and had gone to live in the palaces of the environs during the Summer, and on the shores of the Black Sea in the Winter.

A strong feeling was aroused in certain circles at that time, in favor of bringing the seat of the Government to Moscow, and the Bolsheviki have not done anything more revolutionary in this respect than carry out intentions which in their origin were not of a revolutionary nature at all.

Having become a capital, Moscow, of course, sought to obtain institutions of culture, particularly museums, that were more complete than those that they already had, particularly in the matter of European art up to the end of the 18th century, for the Rumyantsev Gallery of paintings is quite inadequately supplied in this field.

Furthermore, the Bolsheviki are inclined, as I have said above, to multiply the numbers of centers of culture and to make of the museums above all establishments for popular instruction and education. Among the museum custodians on the other hand, there predominates the idea of preserving art works and engaging in special studies, to be carried out by connoisseurs and technical men: they naturally are in favor of an accumulation of works in a single place, and to retaining them in the place that is traditionally theirs. Besides, there is a great number of museum officials in Russia, as one may learn from Polovtsev’s book, who have a certain affection for the historical memories under which the collections were accumulated and for the princes who collected them.

The Ermitage Collections Returned in 1920

The result is two diametrically opposed points of view, and a struggle between the custodians representing the old régime and the new Central power. In the specific case of the Ermitage, more for material than for spiritual reasons; there was not sufficient space available at Moscow, any more than in any of the provincial cities; it would have been necessary to construct buildings, and in view of the famine of materials and foodstuffs, in the midst of the political preoccupation with the defense of the Government, attacked from all sides, this was impossible. It was therefore decided that the Ermitage collections should again take their place in their traditional home as soon as Petrograd should no longer be menaced by bands armed by counter-revolutionaries.

The operation of transfer was carried out efficiently and with dispatch, thanks to the intervention of the Commissariat of War. In two days, November 15-17, 1920, all the cases were put on special trains, which arrived at Petrograd on the 18th. On the morning of the 19th, the Ermitage was again in possession of its treasures, and beginning with November 28, the Rembrandt Gallery was again open to the public. By January 1, 1921, the gallery of paintings had been completely restored to its former state and has since been regularly open to the public on Thursdays and Sundays.

This shows how much truth there is in the legends concerning Bolshevik vandalism and the uses to which the canvasses of Rembrandt were said to have been put.

As to the attitude taken by the learned staff of the museums toward the Central Government, this has certainly been much improved by the change in government: under Tsarism their dependence was very definite and they were much more subject to arbitrary acts on the part of the central authority. The Ermitage at present has a supervisory council consisting of all the custodians, members of the Academy, and professors, a body which appoints the new custodians or assistants by election, makes transfers, in short, itself regulates internal affairs. The custodians enjoy a great degree of independence, each in his section, and they are dependent on the director only in administrative matters.

From the start, the custodians very definitely announced their intention not to meddle in politics, but to remain independent as to the technical affairs in their specific branches. The speculation cherished by certain artists, after the revolution—as we shall see below—to profit by the confusion due to the analogous names of certain political and art tendencies, in order to have a preponderant influence granted them officially, led at first to conflicts with the custodians of the Ermitage, who held their ground and refused to admit cubists, futurists, or suprematists, to install themselves as masters in a museum intended primarily for the works of the old art (although it has since become accessible to 19th century works that were formerly excluded).

The socialization of great private estates, the seizure of the most important private collections, as well as imperial palaces, residences and parks, has considerably increased the number and the extent of the public museums: the Ermitage has grown by two kilometers of galleries borrowed from the Winter Palace, permitting a much better hanging of its collections, which have been increased by new specimens, obtained chiefly from the imperial palaces, where many works were buried, and from private collections. But in general, the great private collections have been retained as characteristic units, in their former state. Thus the Yusupow and Stroganov palaces at Petrograd have preserved, in the framework of their 18th century architecture, almost all the paintings belonging to them, which constitute an integral portion of their furnishings.

Private Collections at Moscow.

Similarly, the very modern collections gathered by the great Moscow industrials, Morozov and Shchukin, have remained intact, and it is still possible to see the Maurice Denis and Matisse canvases in the places originally assigned them.

Moscow thus possesses two really great museums of modern French painting, from Manet to Picasso and the cubists, such as may not be found even in Paris, and you must now go to Moscow if you would fully appreciate the work of Gauguin.

The owners of collections who have remained in Russia have not been driven from their homes; they have remained as custodians of their collections on the condition that they make them accessible to the public at regular intervals; they have simply been limited to a smaller number of dwelling rooms. Morozov himself tells this in an interview published some time ago by Felix Fénéon in the Bulletin de la Vie Artistique, issued by the Bernheim Galleries, Paris.

The museums are becoming centers of artistic education, connected with the organization of proletarian culture that will be spoken of later; they give courses and lectures; the custodians and assistants serve as guides to groups of workers and pupils.

All this is necessarily still at а rudimentary stage. For the most part the professors and guides are people of the old régime who are more inclined to maintain ancient memories than to open up the souls of their hearers in the spirit of the tasks of the new time. Comrade Nathalie Trotsky, who is particularly busy in this department, and with whom I had a long conversation on this subject, is fully aware of the necessity of educating a new staff, which, while completely equipped with the necessary technical knowledge, will have a different mentality and will not speak to the people with melancholy longings for the splendor that has been handed down from the old régime, but will bring out the full human value of the art works and will interest the public in the creative artist and in the very source of his inspiration as found in the life around him and in the soul of the people.

Comrade N. Trotsky, who is imbued with the new spirit, frequently encounters the resistance and the misunderstanding of the “specialists” in this matter. Here, as in all other things, the work of revolutionary creation cannot be accomplished in one day nor brought about by any sudden shock. The good will of the people will not be found lacking: in its desire to obtain instruction and develop its mind, it will respond enthusiastically to every attempt in this direction. Although the population of Petrograd has gone down more than half, and although the Ermitage is now open only twice a week (instead of six times before the war), the number of visitors is about ten thousand a month, while it was eighteen thousand before the war; in other words, the relative number has increased considerably.

In spite of economic difficulties, poverty, the lowered vitality necessarily resulting from insufficient nutrition, the Russian people are hungry for knowledge, for experience, for acquisition of the things of which they have been too long deprived, in the domain of the spirit.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v6-7-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201922.pdf