Karl Radek marks Lenin’s note ‘On The Tasks Of Our Delegation,’ as of great importance for the Comintern. Written in December, 1922 for Radek and other comrades attending the The Hague Peace Conference, it deals concretely with the ever-present threat of a new imperialist war, a war Radek feels the working class and the Comintern unprepared for. Transcribed here for the first time.

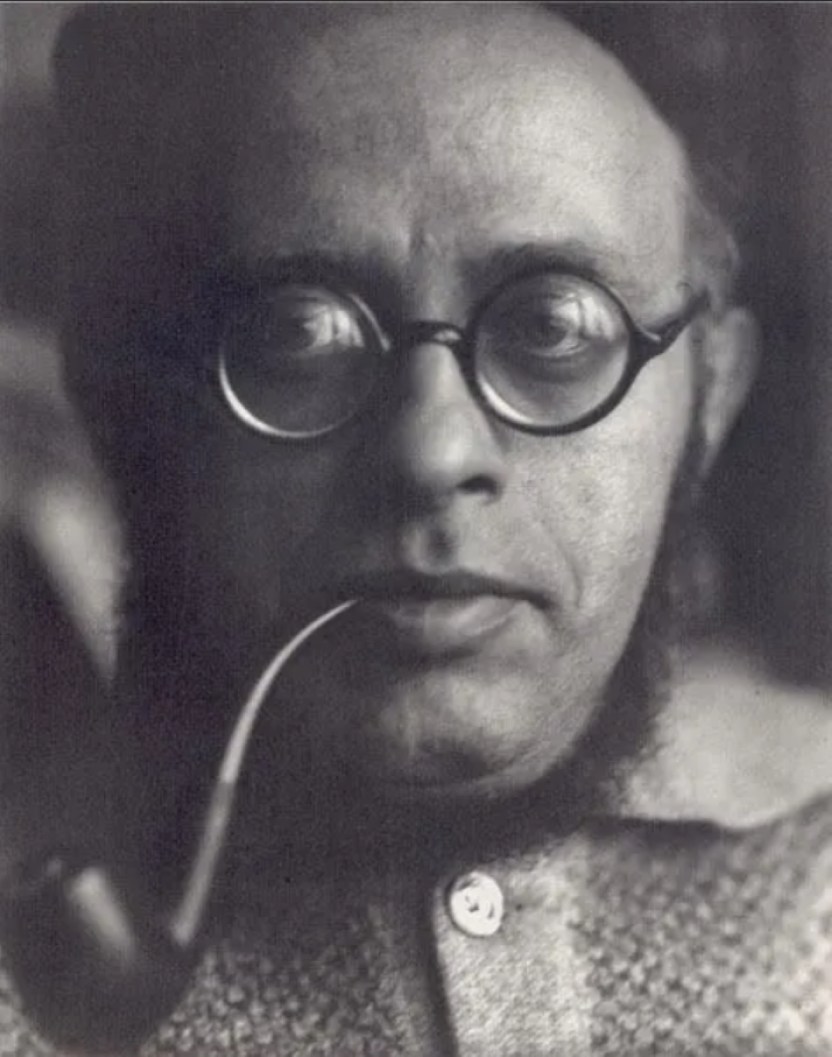

‘Lenin’s Last Political Teachings’ by Karl Radek from the Daily Worker. Vol. 2 No. 91. July 3, 1924.

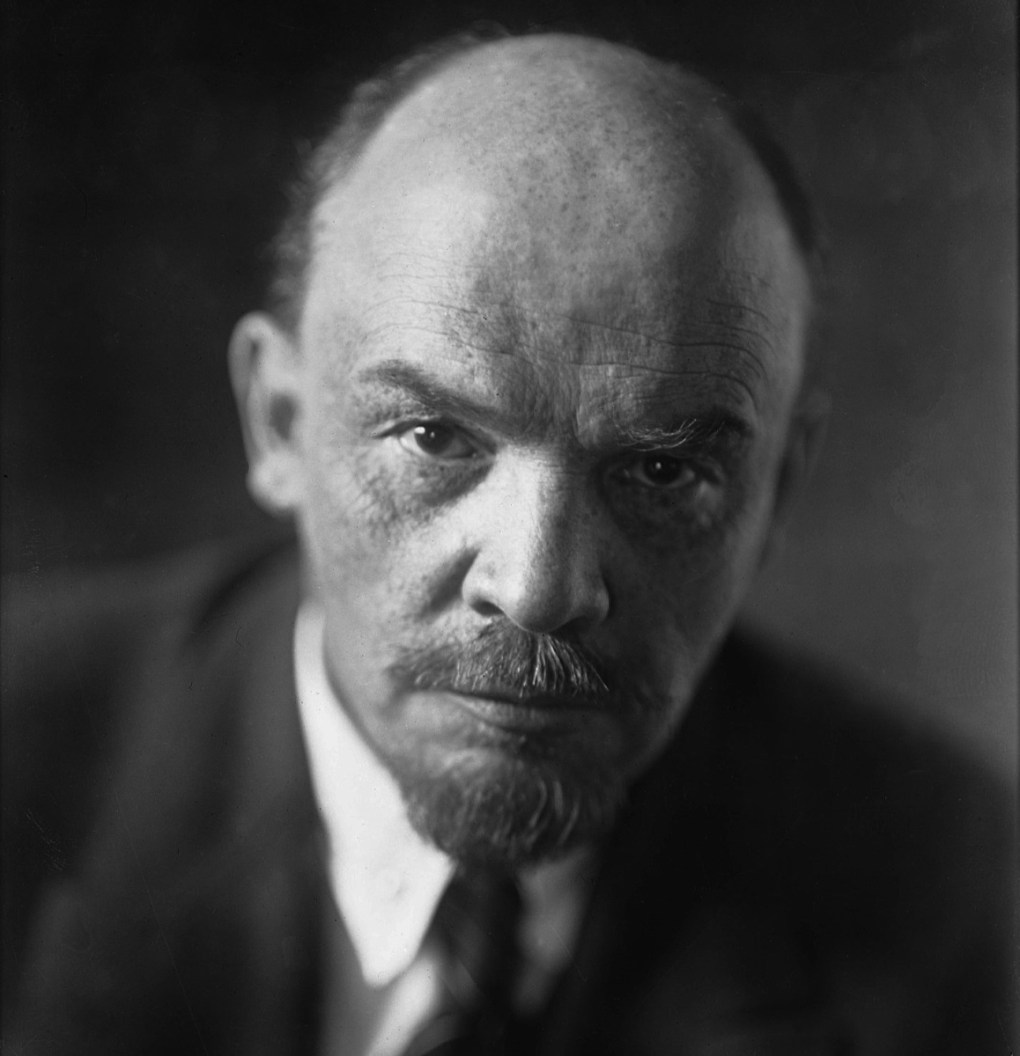

WHEN the All-Russian Central Trade Union Council sent a delegation to the International Peace Conference at the Hague which was convened by the Amsterdam International in December, 1922, Vladimir Ilyitch, Lenin, exhausted by the work for the World Congress of the Comintern just ended, was unable to take part in the consultations held by the Congress of the Comintern of the Russian Communist Party with the delegation of the Trade Union Council with regard to the tactics to be adopted by our delegation. Lenin discussed this question with some of the members of the Congress of the Comintern and drew up a sketch of theses, which was handed me on the day I left for the Hague. These theses may be regarded as Lenin’s last utterance on general questions of Comintern policy. They are of such eminent importance that they must not only be brought to the notice of the broadest masses of revolutionary workers, but must be studied and thought out with the utmost care, to the end that the Comintern and its sections shall draw the concretest practical conclusions therefrom.

Lenin at once seized the bull by the horns. He declared that “none but the completest fools and most hopeless liars could suppose” that we could reply to a war by revolution or strike: “It is impossible to reply to a war by a strike, just as it is impossible to reply to a war by a ‘revolution’ in the plain and literal sense of the word.”

Four years of war and six years of peace lie behind us, and the peace years have not been much better than the war years. Not only do the majority of the reformist leaders quiet the masses of the workers by declaring that they will not be thrown into the jaws of war again as cannon fodder, but the masses of the workers themselves regard a fresh war as impossible, because they are afraid of the possibility. Great masses of workers in western Europe take part in the pacifist demonstrations held under the slogan of “Never again war!” The rejection of the idea of the possibility of war by the masses who have not yet attained to class-consciousness awakens among the communists an over-estimation of their own powers, and an over-estimation of the revolutionary energy of the proletariat. It is for this reason that they frequently, as Lenin observes, make “entirely wrong and frivolous assertions about war against war.”

The great realist and strategist of the proletarian struggle did not shut his eyes to the disagreeable truth: “We give the masses no actual living idea of how a war can break out. On the contrary, the dominating press hushes this question up to such an extent and spreads such a daily veil of lies over it, that the weak socialist press is completely powerless in comparison, the more in that it has always adopted a wrong viewpoint on the subject, even in peace times. Even the communist press is at fault in this respect in most countries.”

Those who peruse our communist press attentively will be aware that it devotes a comparatively large amount of attention to questions of international politics, but with few exceptions publishes but little concrete material on the economic sub-structure of all international conflicts, altho there is an abundance of this material in the international bourgeois press and literature. How many communist newspapers there which devote any attention to the excellent works published by Delaisy on the reparation question, and on the role played in the reparation question by the German and French trusts? How many of our communist newspapers follow up the struggle between the American and English naptha trusts, one of the motive powers of international post-war politics? Works dealing concretely with these questions are read with the greatest interest by the workers. Three editions of my pamphlet on the Genoa conference were sold out in Germany within a few months. The heads of the party pay less attention to these questions. At the time of the beginning of the Ruhr struggle an excellent pamphlet was written by two young German Communists, Friedrich and Leonid, dealing with this struggle. This met every requirement demanded by Lenin for such pamphlets. It was short, running into about thirty pages, and it was based on accurate and clearly out-lined facts. But it was two months before the party issued this pamphlet. In Russia we published a great deal of material on the Ruhr struggle, but “The Young Guard,” which undertook the publication of these brochures, could not bring them out for many months. We could cite dozens of similar examples. And we do not even accomplish the most necessary work towards enlightening the communist vanguard of the proletariat as to the approaching dangers. I give another example. An English war specialist on the question of chemical warfare, Major Lafargue, published a book in the English language: “The Riddle of the Rhine,” in which he drew a frightful picture of war chemistry and its attendant dangers. This book should be in the hands of every communist agitator. It should be popularized in pamphlets and in thousands of articles. But there has not been one single communist newspaper in the west which has taken any notice of it. Our revolutionary council of war has now had this book published in the Russian language. But our newspapers make no comment on it. No practical difficulties lie in the way of our propaganda and agitation in questions of international policy. In the Comintern we possess a number of comrades thoroly versed in international politics, as for instance comrade Van Ravenstein in Holland and comrade Newbold in England, who are among the best informed writers on the connections between the English business world and English imperialist policy. And then we have the Polish comrade Lapinski, whose works on foreign policy represent the best analysis of international relations which I have had the opportunity of reading, and comrade Rothstein, who possesses a thoro and concrete knowledge of English foreign policy. Here in Russia we can count among the members of the Comintern such competent and energetic comrades as comrade Voytinsky for questions of the Far East, comrade Brike for the Near East and comrade Tivel for Indian questions. The reports issued by these comrades show their competent knowledge of their subject, but at present these reports are only accessible to a limited circle. They could be of great importance for wide circles of propagandists and agitators in the Comintern. It is merely a question of overcoming a certain inertia with regard to the organization of the matter. A wider knowledge of such reports would ensure that ten or twenty of the most advanced workers in all countries could obtain a clear knowledge of the questions of international politics, and would be able to enlighten hundreds, thousands, and millions of workers.

It need not be said that even the best organized propaganda work cannot protect the masses of workers from the war danger. If class conditions do not give rise to a wave of revolution in every country, we are not safe against the impending danger of a world war, of a war which may come despite the fact that even the capitalists fear it. As Lenin rightly puts it: a war may break out any day with no further cause than a quarrel between England and France with regard to some detail of their agreement with Turkey, or between America and Japan over some unimportant difference referring to a question of the Pacific Ocean, or between any of the other great powers with regard to disagreements about colonies, tariffs, or general commercial politics.”

If revolution does not develop in the most important capitalist countries before these latter, having recovered from the world war of 1914, plunge afresh into another world war, then the masses of the workers will again be confronted by the question of defense of native country, a question which, as Lenin observes: “the overwhelming majority of the workers will inevitably solve in favor of their own bourgeoisie.” This is a very hard truth. It is difficult to proclaim this truth after all the lessons of the war, after ten million victims have been sacrificed, after half of the globe has been devastated. But I am convinced that Lenin is perfectly right. When it comes to a world war, the bourgeoisie will not only force the masses of the people to take part in it, but will be successful in deceiving them as to its real nature. And what then? “The boycott of war is an imbecile phrase. Communists are forced to take part in every reactionary war,” declares Lenin. And why they must take part in it he further explains definitely by saying that the sole possible means of combatting war is “the maintenance or formation of an illegal organization of all revolutionists taking part in the war for the purpose of carrying on unceasing work against the war.” It might be thought that this is no very great task. But when we recollect the situation in all countries after the outbreak of the war in 1914, when month after month passed away, and there was still no organization of revolutions fighting against the war; when we remember that the whole war dragged out to its end and still there was no country except Russia successful in creating such an organization to any mass extent, then it must become clear to us that it would be of tremendous importance, and constitute an enormous stride forwards, if we communists could rise as one man against war, as a compact, international organization. The preparation for the formation of such an organization demands closest study of the total political experience gained during the last war, and requires that the communist workers shall become thoroly familiar with every shade of opinion formed during the war in the camp of Socialism, and which form the fundamental principles on which political action will be based in the future.

The tenth anniversary of the outbreak of war is approaching. On this day millions of workers will be better able to mediate over the lessons taught by the last ten years than they can on ordinary work days. The Comintern must utilize this moment for conducting an extensive campaign of propaganda and agitation on the lines laid down by Lenin’s last teaching.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v02a-n091-jul-03-1924-DW-LOC.pdf