The second of two in-depth article on art in Soviet Russia by French anarchist art historian Jacques Mesnil brings his critic’s eye to the vehicles for, and tendencies of, art emerging in Soviet Russia.

‘Art Tendencies in Soviet Russia’ by Jacques Mesnil from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 6 No. 6. May 15, 1922.

The distinguished French critic, having shown in his last article (see Soviet Russia for May 1) the care devoted by the Soviet Government to preserving and expanding its art museums, now takes up the question of the prospects for a new art under Communism as practiced in Russia.

WE are now prepared to take up another part of our subject, for this acquisition of new knowledge, this clash of ideas, this registry of new impressions, this germination of new and fertile seeds in virgin spirits, of which we spoke in our рrevious article, must necessarily also awaken the creative faculties.

In what way has it been attempted to encourage this awakening and what are the first artistic manifestations of the great social transformation that has acted more or less profoundly on all spirits?

The phase now under observation is still that of primitive chaos, in which it is hard to distinguish light from shade. We shall necessarily meet with much confusion, much mere fumbling.

At the outset, let us state that even the first rudiments of the art in which the Communist society would have expressed itself in the most direct manner, the most tangible manner—I mean architecture—are entirely absent.

To be sure, in this respect Russia is one of the worst prepared countries. Under Tsarism, architecture had retained an entirely traditional aspect, and was not even national in its character. Since Peter the Great, the imported European styles had not ceased to reign and to predominate; chiefly the Italian and French. In the architecture of the mansions of the rich, in that of the administration buildings, this double tradition was in force; on the one hand there was a style imitated from the French Empire* style, on the other, one taking its inspiration from Palladio. With these there were joined, particularly in the construction of the churches, an imitation of the ancient Russian styles, from the Byzantian to the national style of the 16th century.

None of the great problems of modern architecture had even been touched; banks, department stores, cooperative offices, people’s houses, railroad stations, great educational institutions, none of these had been particularly studied; and even the German influence, in spite of its proximity and in spite of the active propaganda by which it was being spread through books, had exerted but a slight influence in Russia. Notwithstanding the extraordinary development of theatrical art in Russia and the particular interest attached to everything connected with the theatre, the architectural problems raised by this art seem to have been completely neglected in favor of the problems of stage management and scene painting. Here again there is not a trace of the continued and fertile effort made in this direction in Germany.

Similarly, the new methods of construction, such as reinforced concrete, have been very little used in architectural works as such, and have not been studied at all from the standpoint of their artistic possibilities. Since the Revolution, not only has nothing been constructed (which will be understood), but nothing important has even been planned; an over-ambitious attempt to expand the city of Moscow was quickly abandoned.

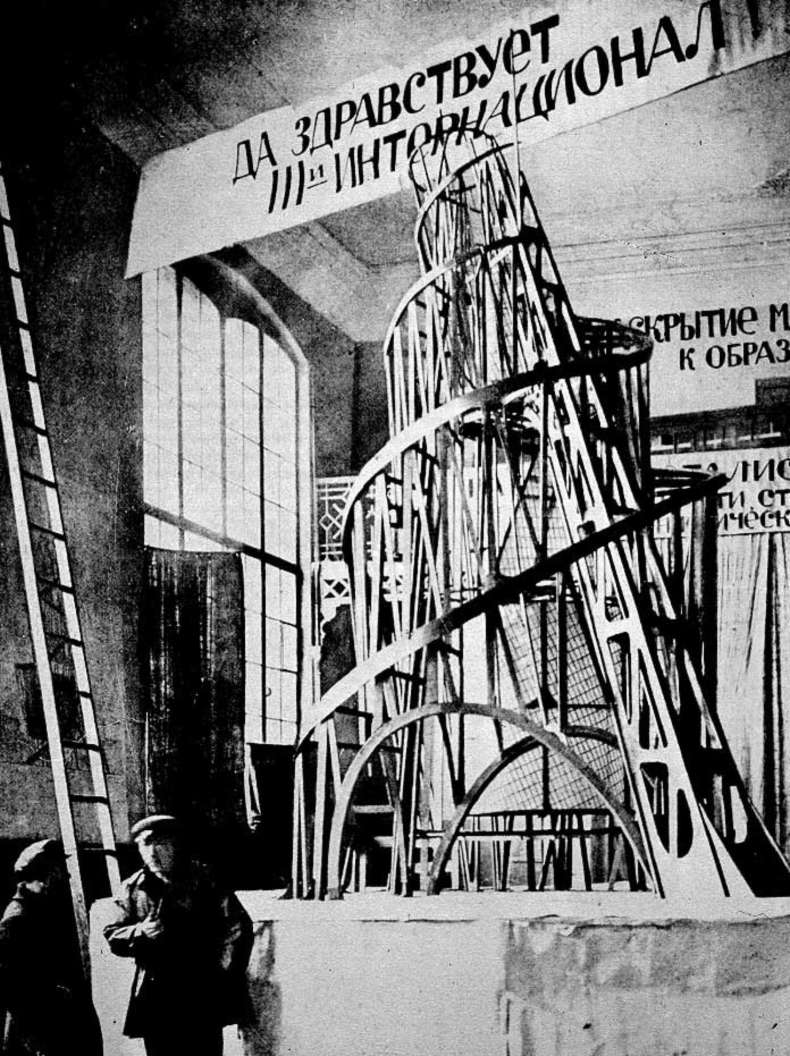

Monument of the Third International

Last Summer there was exhibited at the Technical Exposition connected with the Trade Union Congress a model of a monument of the Third International, in my opinion a disjointed work devoid of any artistic plan. This monument, consists of a great spiral of metal, presenting the same appearance of a gigantic scaffolding as does Eiffel Tower, in the interior of which there are suspended geometrical solids of glass, with ribs of iron or of brass; below, a cylinder about 80 meters in diameter, destined to hold the Congress Hall of the Third International, rooms for stenographers, a library, a restaurant; above it, a pyramid for the sessions of the Executive Committee; then a cylinder, somewhat smaller, for the radio station; and finally, at the top, an electric light and power station, in a hemisphere; each of these solids was intended to revolve; the great cylinder would perform one complete revolution per year, the pyramid one every month, the smaller cylinder one every day, the hemisphere one every minute. This movement was to symbolize the constant movement of the International, while the glass was to stand for the clarity characteristic of this institution, and so forth.

This notion was the work of an artist who was not an architect originally, but a painter, Tatlin, a young professor of the Petrograd Academy, who has played an important part in the artistic world since the Revolution. Taking futurism as his point of departure, Tatlin finds the machine much more interesting than the man, and would like to impart to art a mechanical rather than an organic basis; he confuses machine technique with art and wipes out all the dividing lines between the arts. He has substituted for plastic art a sculptural painting, inventing what he calls “counter-relief”, by the aid of which he represents “machine quintessences”, making use of all possible kinds of substances and objects: wood, glass, tin, screws, electric armatures, microscope lenses, etc.

Criticism of Tatlin

As a matter of fact, it is hard to see what connection all this may have with Communism or with proletarian art. This fanatical admiration of the machine is quite a “futuristic” trait, derived directly from an over-industrial civilization, produced by capitalism in the last phase of its evolution, and from the materialism, in the nonphilosophical sense of the word, which is the consequence of this civilization. The Italian futurists are much more logical than Tatlin, since they directly associate with their art their nationalistic imperialism and their love of war for war’s sake. The pyrotechnical hymns of Marinetti would harmonize perfectly with the machine quintessences of Tatlin.

At the beginning of the Revolution there was a mental confusion, which was inevitable, between the so-called revolutionary tendencies in art and those tendencies in politics that were designated by the same names. This confusion was inevitable because it existed before the Revolution, and because it has been accepted everywhere in our day. In the socialist papers, all precise ideas in the field of art are most often absent, and support is given to extremist tendencies, to “advanced” art, merely because of the verbal analogy, without giving thought for a moment to the fact that in reality the thing thus designated is in most cases a product, an expression of the system that is being fought; and, on the other hand, artists as yet not recognized consider themselves to be revolutionaries and seek the support of persons who run no risk of receiving the stamp of academic approval.

Lunacharsky’s Attitude Toward Art Innovations

Lunacharsky, who is admitted, as we have seen, to be a man of taste and intellectual refinement even by an outright adversary of his political ideas, encourages the tendencies to innovation in art and apparently hesitates to refuse assistance to the young talents. And this is not because he is laboring under any illusions as to the real value of these artistic movements; he has himself said, on the subject of futurism, that it is “a continuation of bourgeois art with the addition of certain revolutionary postures.” But Lunacharsky does not wish to run the risk of throwing out the wheat with the chaff.

He left a free hand to all the futurists, cubists, expressionists, suprematists, imaginists, etc., who confused the triumph of the revolution with their own triumph. These artists had thus obtained for themselves a position of first importance in the artistic organization of the new régime, which was the easier for them since they were attached to this régime, either by conviction, or because they saw in it an opportunity to advance themselves under more favorable conditions than under any other régime. They exerted a preponderant influence in the Collegium of Fine Arts, of the Commissariat of Public Instruction. The former imperial academies were suppressed; in the new institutions, the professors are elected by the students: as the so-called “advanced” tendencies in art predominate among the young, the majority of the professors elected by them belong to the post-Impressionist generation.

Umansky, in his book on the “New Art in Russia” (Neue Kunst in Russland), defines the artistic evolution of Russia in the last few years as follows: “From the representation of nature to pure artistic creation; from the static to the dynamic; from the impressionist disintegration of the object to its increasingly severe analysis; by excluding everything that is temporary and accidental, toward an architectonic moulding of the image; from the empirical world of the phenomenon to the transcendental world; from the monothematic to the polythematic; from the rhythm of nature to the modern rhythm of mechanism; from the imitation of nature to a personal artistic creation, independent of the model.”

In many ways, this program is the antithesis of popular art. The so-called vanguard artists had every opportunity to develop this program in the numerous State expositions organized by them and in public festivals to which they had been appointed as decorators.

Fields for the New Artist

In 1918, the festival of the first anniversary of the Revolution (October 25 O.S.—November 7 N.S.) was organized almost entirely by the guilds of “expressionist” artists; the painters produced gigantic decorations covering the entire facades of buildings, completely changing the character of structures and even of parks, substituting the violent color-play of Russian toys and stage scenes, or ancient church designs in the national style, for the facades of uniform tint and European outline, of the modern houses.

The decoration of propaganda trains also furnished them with a pretext for giving free play to their fantasy. They organized a special museum for their works; finally, they have had numerous expositions: in 1919 there were not less than 13 such expositions at Moscow, including 28,000 works, and more than 300,000 admission tickets were distributed.

In May, 1918, a great government competition was held for plans of about sixty new monuments to the great revolutionists of the world (in the scientific and artistic field, as well as in the social field). Not much is now left of the plaster casts that were set up on the squares of Moscow. Nothing was definitely carried out, owing to lack of the necessary material, and also because the plans were in general of mediocre value.

Nor has much remained of the festive decorations, even in the memory of the people, and these attempts seem to have left an impression more of amazement than of admiration.

The propaganda posters, the object of which was above all didactic, but which might have acquired more than a temporary value if executed artistically, are not in general of great merit and are hardly worth more than the war posters of the various countries that were dragged into the great World War.

The efforts of the artist innovators seem to have been somewhat more fruitful in the field of decorative art; there, the element of representation, of formulation of the external object, is no longer resent, or rather, there is no longer any reason or conciliating it with the artistic treatment, there is no longer an opposition between the object of nature and art; the object itself is the substance of art and the creative spirit no longer needs to conciliate contrary elements of nature, but to harmonize its inspiration with the primary motive of the work. The decorative art studios, particularly the “First Studio of Moscow”, under the direction of Malyevich, the “suprematist” painter, exhibited in July and August, 1919, works in textiles and pottery, the former of which appear really to have been quite remarkable. The young expressionist artists attempted to make popular among the people the decorative motives invented by them, and the peasant women executed embroideries from their models.

But it does not seem that these attempts had any permanent effect: the activity of the decorative art studios has slowed down; the recent products of ceramic art, which I saw last year, particularly the cups made for the Third Congress of the International, were not of great artistic value and were more attractive by their lively colors than by the rhythm of their lines and the general harmony of their forms and ornamental motives.

To-day there is a visible reaction in Russia against the preponderant influence of the futurists, etc. The recent regulations, issued last year, are an evidence of this; an entrance examination has been provided for, which must be passed by all who entered the Academy after 1918. It is held that these students have not given sufficient guarantee of serious talent. I have heard it said that Tatlin, who has played an important part since the Revolution, has been a disintegrating influence in the Academy, even in a material sense.

The Theatre of Today

The effect of the Revolution has thus far been far more important in the theatre than in the plastic arts. The Russians are peculiarly gifted for the theatre, and this is true in every direction, in singing, in acting, in dancing, in scene painting, and in dramatic creation.

We have had a number of echoes of this condition in the West: the Russian ballet has had great success, as is well known, at Paris and elsewhere; the Bat Theatre of Moscow (Chauve-Souris), which divided in two and came to Paris last Winter to give its performances, has revealed a type of vaudeville theatre far above our own in quality.

But all this, I repeat, is only a simple reflection of theatrical art as it exists in Russia, as it can be appreciated only in Russia, in spite of the obstacles placed by material difficulties in the way of actual realization. It is difficult to form an idea here of what the theatre is in Russia, not only in its most refined manifestations, but also as a whole. I was in Russia after the theatrical season, I witnessed chiefly popular performances, carried on with insufficient means, on stages that were too small, with too few performers, a diminished orchestra—when there was any orchestra at all, and not merely a piano—and yet all these performances have left unforgettable memories with me, for the actors do not play their part, they live it, they enter into it absolutely, they are transformed into the persons they represent. Never do you feel that they are trying to distinguish themselves at the expense of the work. This conscience, this religious spirit, which is one of the characteristics of the Russian people, is observable here also. And this trait of character will be the more appreciated by those who know what are the conditions under which actors now work in Russia.

Hardships of the Actors

Exhausted by material privations, frequently fainting with fatigue between the acts, obliged to walk miles on foot from their homes to the theatre, because of the lack of tramway services or the impossibility of sitting down, since the cars may be filled with workers, they are obliged to give lessons or benefit performances, in the attempt to increase the insufficient rations furnished them by the State. They must possess an extraordinary love for their art to give themselves up to it as they do, body and seul, and to communicate such powerful impressions to us.

The theatre is truly popular in Russia, not only because it draws crowds, but also because it draws from the bosom of the people its best elements. Some of its greatest actors, such as Shalyapin, for example, are a direct offspring of the people. And you must have heard Shalyapin sing a worker’s song, and carrying away a whole theatre full of workers to join with him in the chorus, to be able to understand the intimate contact which exists between the people and him, and the exceptional artistic gifts of this people—for nowhere could you find an improvised chorus that would ` make such an ensemble effect and sing with such depth of sentiment.

At any moment, the theatrical calling becomes apparent in the bosom of the masses; therefore the Soviet Republic has done everything in its power to encourage the growth and recognition of such talent. It is one of the principal tasks of the institution destined to develop proletarian culture (an institution called for short Prolekult) to seek out those of artistic talent and to furnish them the means of expressing this talent.

As soon as artistic, musical, theatrical or other aptitude has been discovered in a worker, he is permitted to work only in the morning in the factory; in the evening he goes to practice in the Proletkult headquarters, and if it is considered there that his talent is a good one and that he should be given permission to devote himself entirely to art, he ceases to work in the factory, in order to complete his education in the Proletkult.

The Number of Russia’s Theatres

After the Revolution, a great number of new theatres was established, not only in the great cities, the capitals of provinces, but even in the small towns and villages. There are now 2197 theatres in the Soviet Republic; 268 People’s Houses have a theatre attached; besides, there are in the villages and country districts 3452 small Artistic Soviets, which occasionally give performances. In 1916 there were about 70 theatres of artistic worth throughout Russia and 130 or 140 mediocre theatres; the latter have been eliminated. To-day, there is a regular theatrical craze; everybody wants to learn to dance, to play, to impersonate.

Many stage managers and theatrical operators of the old régime still remain, either by adapting themselves to the new situation, which is less brilliant and lustrous than once it was, or by espousing it enthusiastically because of the unheard of prospects it opens up. The latter is the case with Meyerhold, who on the eve of the Revolution still believed the theatre was made for a select minority and staged splendid and subtle spectacles at Petrograd in the presence of the Court, while he now advocates a theatre of the masses, made for and by the people.

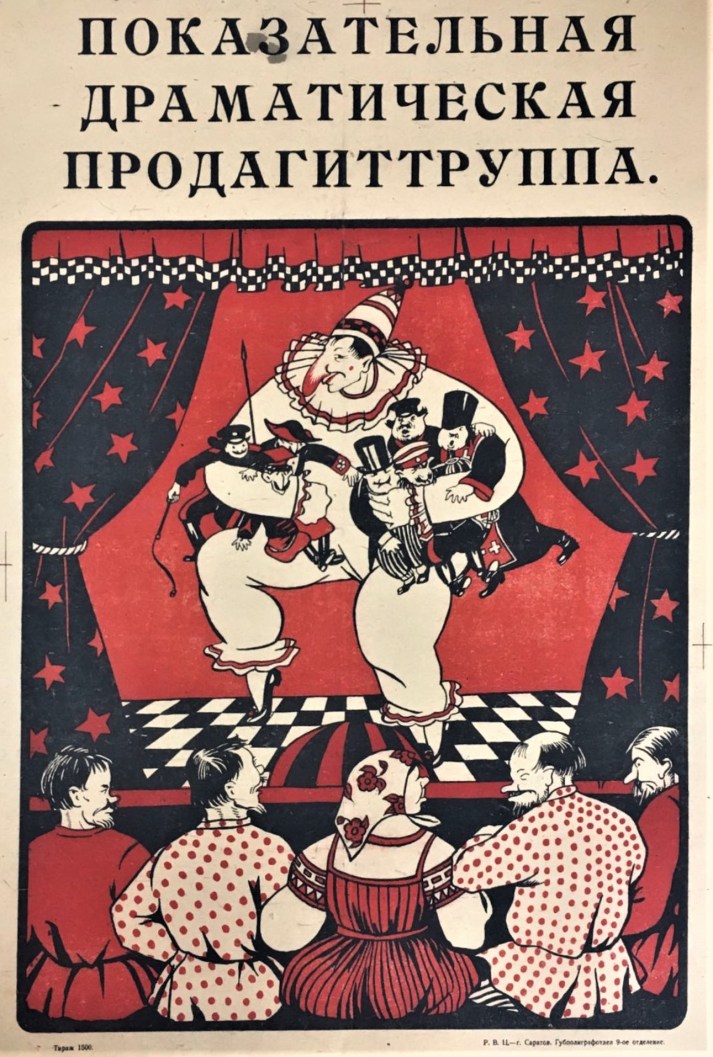

Meyerhold is now one of the most influential persons in official circles as far as the organization of the theatre is concerned. He has created the “First Theatre of the R.S.F.S.R.”, which is considered as the revolutionary enterprise раг excellence in this field. With the greatest care he staged Les Aubes, by Verhaeren, which did not meet with success with the people; then a piece by Maykovsky, entitled Mysteria-Bouffe, which bears the stamp and at present best represents the tendencies of Meyerhold; the very title is a synopsis of these tendencies; on the one hand there is a return to the “mysteries”, to the mass theatre of the Middle Ages; on the other hand, to give it animation, the improvised buffoonery of the old Italian theatre, of the Commedia dell’ Arte, is resorted to. This piece, as far as the subject is concerned, is a bit of propaganda intended to present the Soviet Government, as compared with all preceding systems of government, as the best in existence. Meyerhold flits lightly from subject to subject without any strain. The thing that interests him is stage settings, the great mass movements.

The Audience Become Actors

In Russia there is now a tendency to realize a dream that not only Russians are now dreaming: to extend the art of the theatre outside of the narrow limits of the atmosphere of a single hall, out into the public square; to make the masses participate, to fuse the spectator with the actor.

Kel, who is at the head of the center for political education through the theatre, last Summer stated his plan to André Julien} as follows: “We must create a theatre in which the masses will take part in the dramatic creation. The center for physical and military education, which is obligatory for all, will aid in the preparation of the masses toward this end; it is necessary to bring together the two currents of physical and artistic culture, in order to realize the motto of the ancients: Mens sana in corpore sano. The author will build the skeleton of the piece; the stage manager will adjust the ensemble and the general effect. At the moment the crowd is to take part in the action, the spectators will be carried away to sing with the actors, to live in the performance; they will be seized, as is the artist, with the desire for creation.” Is this plan feasible, and will it lead to anything more than disorder and cacophony, unless everything has been precisely arranged in advance? I must leave to others the giving of a reply to this question—the more since I have not had an opportunity to witness any of these open air performances in which the masses take part, which have been described by several of the authors who recently traveled in Russia, particularly by Arthur Holitscher in his remarkable book, Drei Monate in Sowjet-Russland. Holitscher was present at а performance to commemorate the November Revolution of 1917, which featured the taking of the Winter Palace at Petrograd, making use of the very spot at which this event took place. Nothing was lacking; neither the armed revolutionists, rallying by the thousands from all the adjacent streets, nor the rifle shots, nor the rattle of the machine guns, nor even, at the end, the cruiser firing on the Palace from the Neva. And the spectacle was so impressive, the enthusiasm of the crowd so great, the life which it emanated so kindling, so infectious, that the passive spectators who watched from the windows of the neighboring houses felt themselves conquered by this formidable force and asked, being seized by physical agitation, whether this was not the Revolution itself which they were witnessing. This final use of brute and material emotion, in order to bring reality to the sublimated emotion of the dramatic work, which is intended chiefly to touch the soul, is it a desirable thing? I do not think so, from the artistic standpoint; but it certainly indicates an extraordinary talent on the part of the improvised actors, on the part of this entire crowd, which enters so thoroughly into the play, that it seems to forget that it is merely playing, and thus brings back to life the action that it is supposed merely to mimic.

Meyerhold Contrasted with Stanislavsky

You understand what is Meyerhold’s general direction. Stanislavsky, who was and is still the director of the Art Theatre at Moscow, has not been converted to these ideas. He retains his respect for the finished work of art, in which nothing is left to the chance improviser, and is much concerned with a perfection of execution, doing full justice to the work, that will be as painstaking in the details of stage management as in the play of the actors. In his theatre, in which everything is a result of reflection, in which they live by art and for art, it is not customary even to applaud. This is the principle of absolute non-participation, physically, of the spectator in the dramatic action; we are dealing here with the precise opposite of Meyerhold’s tendencies.

I shall not allow myself the vagary of designating Meyerhold’s tendency as more advanced, and Stanislavsky’s as more conservative; these are terms that have not much meaning in art. But, I must note that Meyerhold’s method, although it may appear to be more popular, does not seem to meet with any particular favor with the people as a whole. The people continue to think much of the old masterpieces; when the celebrated actor Yuryev, of the Grand Theatre at Petrograd, resumed performances of Oedipus Rex, in May, 1918, he had an enormous success, which impelled him to restage Macbeth, Don Carlos, Othello, King Lear, all of which met with equal success.

Leo Matthias, in his interesting study on the theatre in Soviet Russia, translated and printed in L’Art Libre (September, 1921), also points out this preference of the public for the old repertoire and particularly for the plays of Ostrovsky, the most popular of the Russian dramatic authors (1823-1886). Ostrovsky is a peculiarly Russian writer, who, in plays that have an extremely simple plot, put on the stage a great number of characteristic types such as one meets, of every day life, types borrowed chiefly from the merchant class of Moscow, with which he was well acquainted.

This tendency of the Russian public to value plays for their dramatic quality and not for their subject or their greater or less timeliness, modernity or novelty, furthermore speaks in their favor and proves that they have a true artistic sense.

It would be bold to attempt to draw from all these remarks and observations, which are necessarily incomplete, a conclusion of any general application, or any prediction as to the artistic future of Russia.

The Future Difficult to Foretell

But what I have learned, and what I have tried to set down here, is the wealth and generosity of this human soil, the fertility of this people, the multiplicity of the possibilities of these talents for the future.

The Russian people really seem to have the character that is displayed in the works of its writers: Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Gorky, and so many others; their works are capable of moving us far more profoundly than the works of French, German, or English authors. There is a more serious voice, more gripping, more sincere, more profound, more directly human, that speaks to us through them; it is the voice of the Russian people, an unspoiled people, uncorrupted by the reading of the newspapers, by the flickering of the moving pictures, a people whose profound life has not been varnished over and hidden by a uniform veneer of superficial notions and acquired opinions. Often, in reading accounts of the life of these people, or in hearing tales of the events in its present history, I have thought of the peoples of the end of the later Middle Ages, whose spirit I sought not so long ago to trace in the archives and monuments of Florence. Like them; the Russian people is capable of brutalities, excesses that frighten us, but also of great movements of pity, of love, of enthusiasm; like them it is religious; like them it is profoundly artistic.

A movement as formidable as this revolution, which has stirred the profoundest layers of the population and called them to political activity, which has forced them in some way to take part in public affairs, even though they were formerly held down tightly by an autocratic power; a revolution which has brought an entire world of new ideas, not in words, not in books reserved for the initiated, but in actual living reality, and which everywhere has raised passionate discussions, cannot but exercise an enormous influence on the collective and individual life and on the work of art which is its expression.

There is no doubt that art in Russia will reflect this convulsion of the social foundation; we may expect a magnificent efflorescence from the soil thus agitated to its depths. But, again, let us not be too much in a hurry, and let us not expect the miracle of a blossoming conjured up by charm before the new seeds shall have found a soil of comparative stability in which to germinate.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v6-7-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201922.pdf