A major address by Bebel given in Munich on April 7th, 1906 in which he discusses the political situation in Germany, the imperialist struggle for Morocco, Russia’s Revolution, militarism and and Great Power diplomacy, colonialism, and the International.

‘The Political Situation in Europe’ by August Bebel from International Socialist Review. Vol. 7 No. 1. July, 1906.

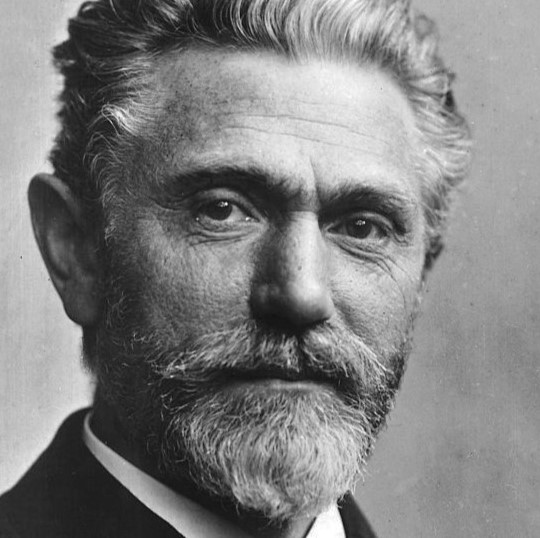

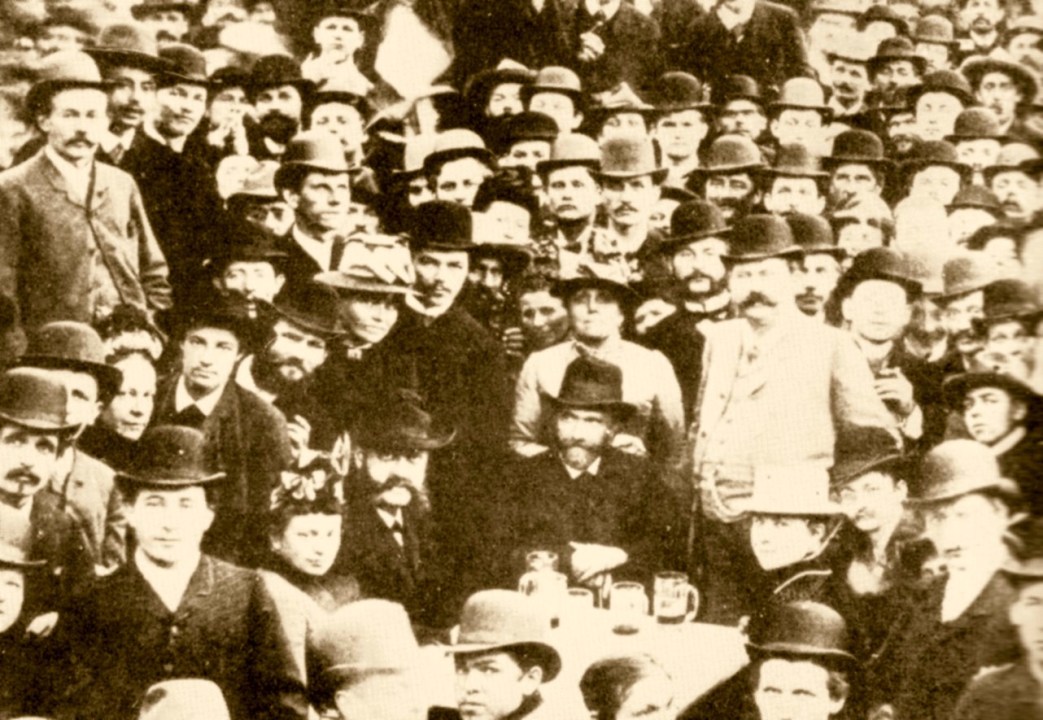

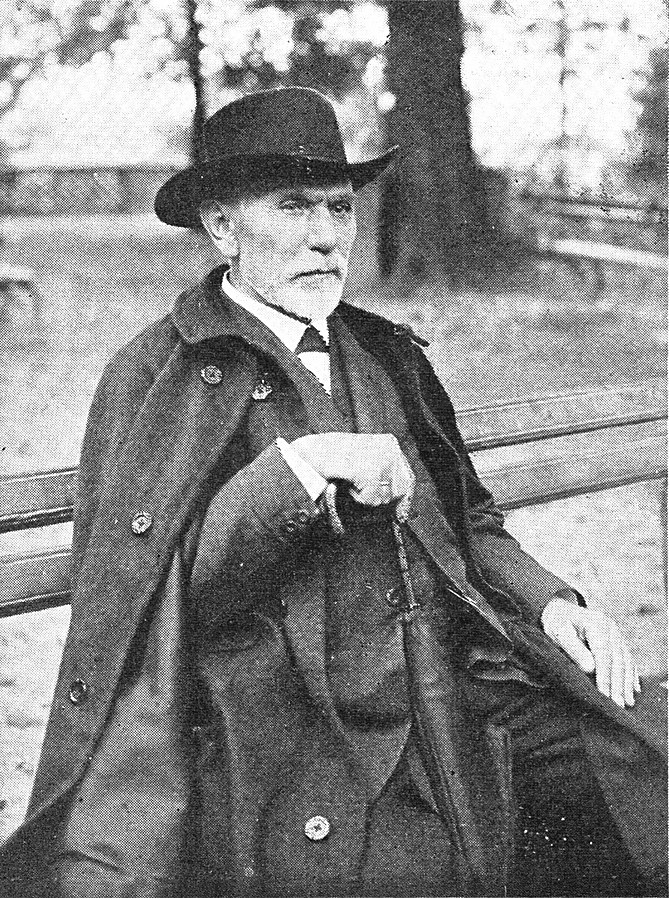

Not since the Congress of the Social Democratic Party which took place in the summer of 1902, have the Socialists of Munich had an opportunity to hear an address by August Bebel, leader of the German Social Democracy ; and consequently, although the meeting at which Bebel was to speak was called for eight o’clock, the great hall of the Kindlkeller was well filled at six, and at seven the crowd had become so dense that the doors were shut by the police. From five o’clock in the afternoon a steady stream of workingmen had been pouring into: the building; an hour later every seat on the floor was occupied. Late comers were either obliged to stand or to take a back place in the galleries. Shortly before eight Bebel appeared, a storm of applause bursting forth as he slowly made his way to the platform. August Bebel was 66 years old on the 22d of February; his hair and beard are white, but he is still Bebel the “ever-young.” His step has lost none of its elasticity; he is as agile in his movements and gestures as a man of thirty years, and his voice retains all its extraordinary carrying qualities and power. Slightly below the middle size, spare in figure, and unassuming in dress, there is but little in Bebel’s external appearance to suggest the political genius and orator: like our own Lincoln and Wendell Phillips, we must hear him speak to be disillusioned. He spoke as follows:

The world of the ruling classes is always fighting for peace; we are assured by all governments that peace must be maintained for peace is necessary to the labor of civilization, — peace is the most valuable possession of mankind. Yet in contradiction to this assurance, all the nations of the world are striving to outdo one another in the construction of the most elaborate and costly armaments that have ever been known to history.

If we ask the ruling powers how they manage to bring their assurances of peace into harmony with their preparations for war, we are told that in order to have peace it is first necessary to be armed to the teeth. But no nation trusts another, and no one takes the assurance that peace is desired seriously. The world of the ruling classes indeed requires peace; its dominant principle is on the one hand labor, and on the other hand profits from labor and the accumulation of capital. To-day, no country in Europe, if forced to depend upon its own resources, would be able to exist; and however much we Socialists are reproached for our international tendencies, the capitalistic world is itself compelled more and more to realize the spirit of internationalism. Each nation must enter into relations with other countries for the mutual exchange of industrial, agricultural and natural products. For this reason we have every reason to believe that the most obvious duty of the ruling classes is to maintain peace. And yet, every moment some question or another arises and seems to threaten the entire civilized world with a sudden outburst of hostilities.

Hand in hand with the work of exchanging the products of one nation with those of another goes the endeavor to conquer new markets in all quarters of the globe;—an endeavor which has also made its appearance in Germany. But as a matter of fact, everything in the shape of colonial territory that is worth the trouble of annexing has long been annexed. Like the poet in the fable, when it came to dividing up Germany arrived too late. From my present standpoint, there was no harm in that; for we exchange our products with civilized nations, not with Hottentots and Zulus. In 1905, Germany’s foreign trade mounted up to the fabulous totals of thirteen thousand million marks (three billion dollars), and now I ask, what are the countries with which we have commercial relations? During the last few months there has been a great deal of discussion in regard to our relations with England, and not a few of our fellow countrymen suffer under the delusion that our first and foremost duty is to strain every effort to drag England down from the position which she holds to-day, and above all to make an attempt to seize for Germany one or more of the English colonies; for it is said in confidence that the colonies now owned by Germany are not fit to grow cabbage on. Yet twenty-four per cent of the foreign trade of Germany is with England, and in spite of all differences of opinion between the two countries, it increases from year to year, — an unanswerable proof that the material interests of nations are more powerful than personal likes or dislikes. Our trade with the United States amounts to some fifteen or sixteen hundred million marks ($375,000,000). From America we obtain for the most part raw materials and foodstuffs that are absolutely indispensable to our welfare; for at home we are unable to raise and produce all that is necessary to supply our needs. Besides England and America, we have commercial relations with Russia, Austria, France, — in short, we can prove statistically that by far the greater part of our foreign trade is with the leading civilized nations of the world.

From this point of view, and considering their mutual necessities of life, it is madness for civilized nations to wish to measure their strength with one another in the battle-field, instead of by way of peaceful competition. And yet those questions are constantly arising, as a result of which the world is confronted with the danger that some day the very thing that is dreaded most by all may happen, and a general conflagration burst forth between the leading powers. Such a question, which made a sudden appearance about two years ago, was

THE MOROCCO DISPUTE.

Morocco, a barbarian Mohammedan state in North Africa, is a country of extensive area and large population, two-thirds of whom, however, do not acknowledge their own Sultan, let alone any foreign ruler. It is a backward country, — backward in industry no less than in civilization, — although beyond doubt it possesses many possibilities of development. Since it is situated so close to France and Spain, it is not to be wondered at that these countries were anxious to establish themselves there. England also was greatly interested in Morocco, and at on time it almost appeared as if there was going to be war between England and France for supremacy in that country, But to everybody’s surprise an agreement was entered into by France and England, April 8, 1904, according to which, in spite of their strongly opposed interests, France agreed to recognize England’s position in Egypt and the Sudan, and England agreed to give France free hand in Morocco. There was a clause in the treaty which to a certain extent injured German interests, but, strange to say, Prince von Bülow declared at that time in the Reichstag, that Germany had no cause to be dissatisfied: for even if France did take charge of the affairs of Morocco, German industrialists were perfectly free to compete there if they chose. We may say in passing that German trade with Morocco amounts to about four million marks (less than $1,000,000) a year, — a mere bagatelle compared to the 13,000 million marks of German international trade.

But the situation soon changed. It now appeared that what Prince von Bulow had praised as an acquisition, was after all of doubtful advantage. And as a matter of fact, the treaty contained a clause, according to which Germany was given the right to trade in Morocco for a period of thirty years only. We too thought that there was something wrong in this, but were of the opinion that the danger to which the nation would be exposed by a hostile interference in the affairs of Morocco was wholly out of proportion to the value of the object to be gained. However, the Morocco affair soon became a question of this nature. In a French document the suspicion is voiced that an attempt was made to convince the German Emperor that in consequence of the unfortunate outcome of the war with Japan, Russia would no longer take the part of France. And it is quite possible that this suspicion was founded on fact; for a short time afterwards an event took place such as had never before happened in the intercourse between nations, —at least for the sake of a matter of such small importance. The German Emperor sailed to Tangier and talked to the representatives of the Sultan of Morocco in such a manner as could only heighten their feeling of self-importance and at the same time arouse a most unpleasant impression in France and England. It was not until the occurrence of this event that Prince von Bulow began to talk about an impending catastrophe; and Delcassé, the French Minister of foreign affairs, is said to have inquired of the British government if it would be willing to support France in case of a war with Germany.

It is a long time since England and Germany have been on friendly terms. A whole series of events, among others the celebrated telegram to President Paul Kriiger, has tended to estrange Germany and England more and more from one another. The result of the Morocco question has been to cause England and France to become permanent friends, — to the injury of Germany. As was only to be expected, Italy and Russia also took the part of France, so that finally Germany was able to reap no other advantage than the abolition of the clause limiting her right of freedom of trade in Morocco to thirty years. All the rest is only of value to France and Spain. And it is for this reason that Prince von Bülow now tries to minimize as much as possible the significance of the Morocco question, — the same von Bülow who last summer is said to have inquired of the General Staff if it were prepared to begin the war! But this most recent declaration of von Bülow’s stands in decided contradiction to the tendency of German foreign policy of recent years; and I fear that it has not had the effect of increasing the prestige of Germany and her diplomacy. We must also remember that during the entire tremendous

REVOLUTIONARY STRUGGLE IN RUSSIA,

Germany has done everything in her power to be of service to the reaction. (Cries of shame!) Germany has even gone so far as to anticipate every wish of the Russian government, besides agreeing to allow a Russian loan to be raised here; and as a reward Russia has just opposed the German claims in Algeciras in a most ostentatious and insolent manner. A more humiliating situation is scarcely to be imagined; but the Russian government knows only too well that Germany is at its beck and call. The heart of our ruling classes, especially the East Prussian agrarian nobility, is with the Russian government. The East Prussian nobility looks upon the Russian autocracy as its ideal, and expects, in case a serious struggle should burst forth in Germany between the government and the people, that if the former should prove too weak to withstand the will of the latter, that Russia would assist it with her Cossacks.

The Prussian nobility is the incarnation of all reaction, the representative of whatever is opposed to the welfare of the people, the enemy of all economic progress. So long as Russia remains a despotism, it is her endeavor to uphold similar political conditions in all adjacent countries. But the war with Japan and the revolution at home have now combined to weaken Russian absolutism, and the ruling classes in Germany, the Emperor, von Bülow, and the East Prussian nobility view with regret the events that are taking place in Russia, and would welcome the day they could see the old conditions restored, — that is, if the old conditions were capable of being restored! But that is a thing of the past. The Russian revolution will not come to an and until the autocracy has been succeeded by a more reasonable social order.

For us, the general situation is not very edifying. We have not one friend left except Austria; but Austria has fallen far behind the times in financial affairs, and in military entanglements financial power is a very important matter. Still, from this point of view, poverty has its advantages. The development of military strength has grown to a colossal extent. In 1900 a conference was held at The Hague to discuss the question of disarmament, and now Russia comes along with

A SECOND PEACE CONFERENCE

— more banqueting and pacific resolutions — and armaments to be increased on sea and land. (Laughter.) There is much reason for laughter; the pacific resolutions will remain written in black and white for the entertainment of future generations no less than of the present. For ten years the idea has been officially promulgated, that Germany also must live up to her interests as a World Power, and we have been told that whenever opportunity offered our national importance was to be clinched by a demonstration. And so we tried to demonstrate in Morocco, — only it did not all turn out quite as was expected. In 1896, the majority in the Reichstag, including even the Conservatives, declared that we had no inclination to compete with other nations in costly armaments, if for no other reason than because the necessary funds were lacking. But since that time, one after another the bourgeois parties have capitulated; and a few weeks ago the naval programme was voted for by all except the Social Democrats. For eight years Germany has endeavored to become at least a second-rate sea-power. In 1905, we expended the enormous sum of twelve thousand fifty-eight million marks on the army and navy; and all the while the national debt has been constantly increasing. Such management as this is enough to bring on a catastrophe even in times of peace. The committee on taxes is searching everywhere for new sources of revenue. And the Clericals are now discussing the expediency of a so-called military tax, in case the present objects of taxation prove insufficient. This is the same Clerical party that in 1900 introduced a paragraph into the naval bill, stipulating that if the naval budget should exceed one hundred and seventeen millions, the surplus should not be raised through indirect taxation. The new proposals for additional revenue are

INDIRECT TAXES

which must be borne by the masses of the people. The taxes that ought to be levied, namely, on incomes, property and inheritances are conspicuous by their absence. During the recent debate on the naval budget, the property tax suggested by the Freisinnige ` Volkspartei, which would have yielded forty millions, was rejected, — likewise the tax on all incomes of over five thousand marks by the Social Democratic group. We want those people to pay who claim that patriotism demands that Germany should require a huge army and navy. We want them to be patriotic not in word but in action. The State is at bottom a great mutual insurance company, and the premiums should be paid in proportion to the services rendered. Since the army is an organization for the defense of the interests of the propertied classes, — it is also employed in the struggle against the “enemy at home”, — and since the navy serves a similar purpose, justice demands that both should be paid for by the classes who seek their protection. But direct taxes on property and incomes are paid by no ruling class, with the exception of the English bourgeoisie. At the time of the struggle in South Africa with its tremendous drain on the finances of England, the English middle class, (and in Germany this must be said to their credit by a Social Democrat) increased the tax on incomes in order to meet the extraordinary expenses of the war, — and in England incomes of less than three thousand marks ($700) a year are free from taxation. In this way the English bourgeoisie were enabled to raise no less than one thousand one hundred millions in direct taxes. It is true that at the same time a duty on grain was also adopted; but whereas we paid here at that time a duty of three and a half marks per double hundredweight, the English duty was only one-seventh of that amount. Moreover, although the English duty on grain was abolished at the end of two years, our duty has been increased to five and a half marks, or almost sixty: per cent. This is the work of the agrarian nobility. Thus while in a nation also ruled by the bourgeoisie, not only the principle of noblesse oblige prevails, but also the principle that the possession of property brings with it responsibility to the public; in our country, the society for the promotion of the interests of the navy, which recruits the majority of its members from the most fashionable circles, had the unparalleled impudence to demand that the entire surplus of the duty on grain, which had been set aside for a pension fund for widows and orphans (30-40 million marks), should be devoted to the building of new warships! I cannot conceive of anything more infamous than that such a desire should be expressed by the wealthy classes of a nation.

Thus armaments have everywhere taken a new lease of life. It is an interesting question how things would turn out

IF WAR WERE REALLY DECLARED.

All the nations of Europe are in debt, and their indebtedness 1s increasing from year to year. What is yielded by taxation just suffices to make both ends meet in time of peace. But how would this be in case of a war? Germany would now place five million men in the field as compared to the one and a half million of 1870. Mobilization alone would cost 700 million marks, of which only the 120 million deposited in the Juliusturm are available. The expenses of the first month have been estimated at 1,400 million marks, and if we were obliged to carry on the war for a year, the cost would be 22,000 million marks. Where is the money to come from? The wealthy classes will not furnish it, and the issue of paper money would immediately be followed by its depreciation. Even granted that we were victorious, does anyone believe that there is a nation to be found capable of paying an adequate indemnity, as was the case in 1870-71? We would have to enslave the inhabitants of entire France in order to clear off the debt. It is also possible that the pension funds would be used for the same purpose. We have been in the habit of granting pensions to the disabled, but considering the increased effectiveness of modern weapons there would now be an appalling number of wounded, and where are the funds to be obtained? We must also remember that of the 5 million troops 314 million individuals would at once cease all productive work. In a war of the future we would have both France and England against us: they would blockade the North sea and the Baltic; trade, both import and export, would stagnate; the millions of workers who remained in the factories would be thrown out of employment; and as a result of the interruption in the importation of the necessities of life, there would be a sudden rise in prices. How would the capitalistic world be able to face such a situation? It is probable that it would be at the end of its tether.

Two years ago in the Reichstag, when I similarly described the probable effects of a European war, and in my reply to Prince von Bülow declared that such a situation would signify that the last hour of the capitalistic order had come, Von Bülow answered: “This we know, and because we know it we will avoid war.” But if that is the case, why these endless preparations for war? We also have a

COLONIAL POLICY,

and our colonies are a heavy expense. If we had to pay for our foreign trade a tithe of what we pay for our colonial trade, we would go bankrupt in one year. We are told that the navy is for the protection of our colonies; but in case of a war we could not even protect our commerce. Our sea coast requires no fleets for its defense; but our trading vessels could be captured and our commerce destroyed. With our navy shut up in the harbors, England could, if she chose, take possession of every one of our colonies.

We Social Democrats are considered enemies of our native country. I have just shown how profound the love of the Jingo patriots is for their native country, so long as it does not cost them anything. When it comes to paying, their patriotism evaporates. They increase both navy and army, and thereby create new sinecures to be occupied by the sons of the nobility and bourgeoisie. The masses pay, and in time of war their sons are the food for powder. The nobility and bourgeoisie are also enthusiastic for colonial expansion, for officials are needed there too. We stand for

THE INTERNATIONAL INTERESTS OF CIVILIZATION.

We are not of the opinion that there will be a general dissolution of civilized nations; but we are opposed to the unheard-of burdens that are laid upon the shoulders of the workers of every nation to pay for the creation of instruments of destruction. We wish to employ this wealth for the furtherance of civilization. We believe that the common interests of nations are growing from year to year, in spite of the endeavors of the ruling classes to erect barriers of protective duties between them. Just as we have a national house of representatives, so should civilized nations have an international parliament for the arbitration of disputes. If we are told that this is idealism, our reply is that all that exists to-day was once idealism. Christianity also is international, and tells us of a God who allows the sun to shine on both the just and the unjust. But these same Christians, when it comes to a conflict between nations, see nothing strange in appealing to an international God for the victory of their own particular nation. We know very well that nothing can be accomplished by preaching: if we desire the internationalism of peoples, we must recognize and strengthen the internationalism of interests. The International Postal Union,—in fact, every commercial treaty is a work of international solidarity. Why can not this spirit of solidarity between nations be infused into all our relations? Where there’s a will there’s a way. The working-class of the various civilized nations, who are everywhere subjected to exploitation and oppression, have but one interest, not only within their own nations, but also in the relations of the different nations to one another. From this the

INTERNATIONALISM OF THE LABOR MOVEMENT

has naturally developed. When the danger of war between Germany and France arose last year, it was the Social Democrats of Germany and France who stood together as one man for the idea of peace.

But it is not only the burden of armaments by which the people are oppressed. On the first of March of this year, the new tariff laws came into force, and the result of these tariff laws has been a general rise in the price of the necessities of life. What one could buy for 100 marks three years ago now costs 120 marks. But in the meantime the income of the workers has not increased; and in this manner must the working class pay the penalty of the military expenses of the nation with poor nutrition, sickness and death. A decade ago there were millions of people in Germany who were insufficiently nourished, and what must their condition be to-day? Even our Jingo patriots will have the effects of the increased cost of living brought home to them, for the number of unfit recruits for the army must increase with insufficient nourishment. A further effect of the new tariff laws is the decrease of our exports, due to tariff wars with other nations.

That our domestic political relations are also in a lamentable condition can be gathered ad nauseam from the newspapers. On the 2oth of January, 1903, Prince von Bülow announced in the Reichstag the social program of the Emperor and the State Governments. The Imperial Chancellor said that the workers should be granted equal rights with the other classes, and that this equality of rights should find its expression in legislation. The German workingman is still waiting in vain for the Chancellor’s words to be realized. A short time ago at a banquet given by the agrarian party, Prince von Bülow spoke of Social Democracy among other things, and said that the Social Democrats are endeavoring to ruin the farmers. But that is precisely what we are not trying to do; what we want is truth and justice in all human relations in state and society. No one shall he permitted to live at the cost of another, or to exploit and oppress his fellow man. We wish to assist the farmer with all our power in his endeavor to obtain better means of conveyance, agricultural schools and colleges, experiment stations, instruction in scientific methods of stock breeding and sanitation; but we are not willing that the prosperity of the peasants should be paid for by the increased cost of living of the proletariat. I have never heard of a peasant starving to death, but starving workingmen are to be numbered by thousands. What has become of von Bülow’s social reforms and equality of rights? Perhaps the continuance of the three-class system of voting is the answer to this question, or the attempted suppression of the right of coalition and of holding political meetings, or class justice! And in view of these conditions, can one wonder that in reply to a question list published in a French newspaper, some of the most distinguished men of Europe have stated that in the interest of freedom and progress they should not care to see the influence of Germany increase? But we will take care that what is said of the Germany of to-day will not be true of the Germany of the future. We Social Democrats demand the freedom of all men; and in order that this demand may be realized, we require knowledge of national and social conditions, unity of action, and the enlightenment of all classes, above all the working class. The workers must learn to know their historical mission; they have no other future except Socialism. And hence I say to you: your future depends upon your own unaided efforts; join hands with the party of the proletariat, support our organization and our press, and then in closed ranks forward to victory!

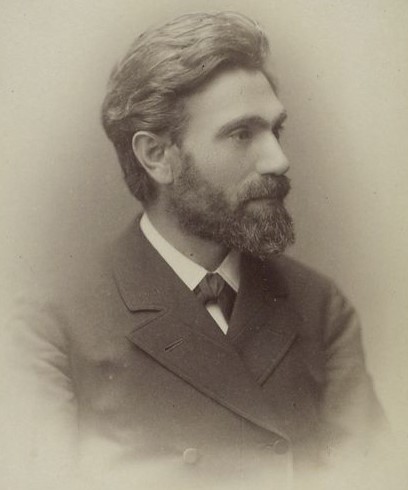

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v07n01-jul-1906-ISR-gog-Harv.pdf