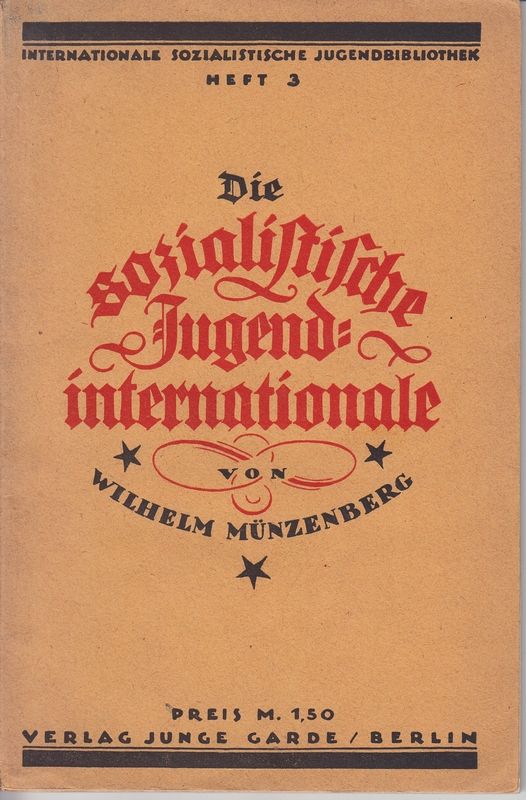

Written by a central participant in the events described, Willi Münzenberg’s extremely valuable history the anti-war youth movement during WWI, ‘The Third Front’ (1929), was translated and serialized by the Young People’s Socialist League at the beginning of the Second World War. Active in Switzerland, where much of the action takes place, Münzenberg’s provides copious details of the comrades, events, and debates of the young founders of the Third International.

‘The Story of the Socialist Youth Movement During the Last War’ (1929) by Willi Münzenberg from Challenge of Youth (Y.P.S.L.). Vols. 3-4. October 1, 1939-February 15, 1940.

A few weeks after our return from Germany, our group was gathered in the People’s House following a hike over the Zurich mountain, when newspaper extras brought us the news of the assassination of the Austrian Archduke in Sarajevo. We immediately found ourselves in an intensive discussion on the con- sequences of this act. Though we all realized that it would lead to severe conflicts between Serbia and Austria, no one at that time really believed that it would lead to a war. The international ties of capitalism seemed to be too extensive and firm to permit this. On the other side we saw the Social Democratic Parties and labor organizations who only a few years before, at the Basle Congress of he Second International, had sworn to struggle against war with all forces at their disposal.

War Begins

But events developed at a whirlwind tempo. Austria sent its ultimatum to Serbia. The danger of war arose. The great chauvinist waves unleashed in Vienna and Berlin had their effect even in Switzerland. Various nationalist German societies arose in the German speaking sections of Switzerland and carried a lively pro-German agitation in meetings and street demonstrations. The ultimatum to Serbia was followed by the declaration of war. Hundreds of Austrian citizens had to leave Switzerland to answer the summons to serve in the military forces. The departure of every group was utilized by the German and Austrian supporters as an occasion for a new patriotic demonstration. The street that ran from the shores of Lake Zurich to the railroad station became the scene of daily demonstrations of hundreds of war-inspired people, who waved the black, white and red flag of Germany and sang patriotic songs.

These demonstrations caused feelings of greatest anger among our youth comrades. We called our members to a counter-demonstration. But our group was too weak to effectively silence the growing chauvinist insanity. Though we were the sworn enemies of the police we couldn’t re- strain ourselves when the Zurich police sought to quell particularly noisy pro-German demonstrations and waded in along side of them to plant our fist upon many an open mouth that was howling for war. One evening we took over the railroad station during the departure of a train load of cannon-fodder for Vienna. The duped recruits and reservists sang at the top of their voices, “God Save Franz, our King.” While we sought with all the power of our lungs with the singing of the “International” and the shouting with “Down With the War” “Up With the Revolution!”

Reformist Fakers

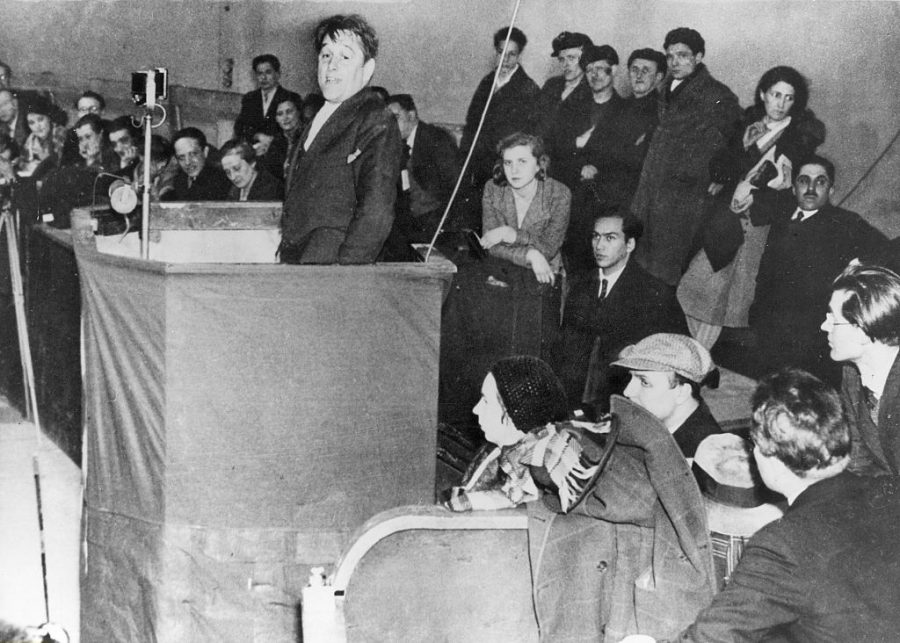

The Central Labor Union called a meeting to take a position on the war. The meeting was packed. An overflow crowd could not find space and were turned away. The first reporter was the Social Democratic reformist, Johann Sigg. He wept many tears over the terrible misfortune. But the idea of a struggle against the war that was impossible. All one could do was to wish for the reconstruction of the socialist and labor movement after the war was over.

It was too much for me. I jumped up to the rostrum and began speaking as the first discussion speaker. I sharply condemned the capitulation of the Socialist parties to the war and demanded the sharpest struggle on the part of the Social Democratic parties and the working masses, particularly in the form of general strikes in Germany and France to prevent the spread of the war and to stop the Habsburg adventure in Serbia. I closed with the statement that we, the youth, had no intentions of fighting in this war, that we would struggle for the cause of socialism to the very end, but would never give our lives for a capitalist war.

Attack Munzenberg

My speech provoked Hermann Greulich, the old Social Democratic ‘Pope,” to take the floor in order to, in the words of the report in the bourgeois press, “pour a little water into the wine of the rebellious youth.” Gruelich granted the best intentions on my part, but declared that there were no means with which to stop the war, that we were too weak, and the individual could not oppose himself to the mighty military machine. It was with this concept that Grue- lich and Sigg led the Swiss Social Democracy during the war.

A few days after this meeting the declaration of war by Germany against Serbia took place and the Austro-Serbian conflict became a World War. The German declaration of war against France called forth a new chauvinist wave among the German residents of Switzerland. In a few days all the German reservists living in Switzerland were on their way home to answer mobilization calls. Not a single member of the German Social Democratic Society in Switzer- land stayed behind. Many of the Social Democratic workers marched back with the German National Anthem on their lips and dressed up as though it were May Day.

Fakers Live

Only a few, not more than a half dozen of the German Socialist Youth and a few Syndicalists and Anarchists remained in Switzerland, despite the attempts of Hauth, the social patriotic editor of the “Volksrecht,” to frighten us with notices in his paper. It disgusted him to know that there were some Social Democrats who were not pre- pared to follow the example of the Social Democratic editor in Chemnitz, Germany, who declared, after the outbreak of war, “I with Hindenburg.”

go Hauth printed false statements in “Volksrecht” to the effect that the Swiss government had decided to deport to their own countries all deserters and draft dodgers. Hauth, however, stayed calmly in peaceful Zurich and only later went to Germany to enlist as a “Home Guard,” with the chief function of agitating for continued support of the war in the columns of the Stuttgart “Tagwacht.”

The war tore great gaps in our organization. Many a member was swept along by the pro- war current and joined the army of one of the belligerent countries. The position of the party assisted this in the most direct sense. But still greater numbers of our members and functionaries were mobilized in the Swiss army. The Swiss government had declared a mobilization a few days before the outbreak of the war to defend its borders and hundreds of our members were involved.

Unlike the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland, the Socialist youth took a sharp and decisive stand against the war from its very beginning. This position was expressed in our speeches, in our open-air meetings, in our street demonstrations, and in our leaflets and newspapers that were published. immediately upon the outbreak of the war.

The first number of our organ, “Free Youth”, that appeared after the start of the war was dedicated in its every line to the struggle against war. The cover carried a full-page drawing depicting war as the horseman with the blood-stained sword with the grim reaper riding in his wake and bore the slogan at the top of the page-We must war against the war!”

Printed His Article

Along with poems, articles, brief items, and other material against the war, the issue carried a lead article by myself, which concluded as follows:

“No matter which side wins the war, it will be the same for the workers in all participating countries. For their interests are not at stake, for the war revolves solely around the interests of the capitalists. And all the nicest phrases cannot change this…

“We are confronted with a great task. The new banner-bearers of Socialism, above all the proletarian youth, must struggle to overcome the failures of the present period, which is disappearing into the morass of the European war.”

The article shows that our Socialist Youth group was clearly and decisively against the war. However, our evaluation of the situation not only lacked the theoretical insight, with which Lenin and his group approached the war, but also the measure of experience which the later war years were to bring. We also lacked, at the time of the writing of the article, any sort of ties with brother organizations in other countries.

2nd International Dies

The organization which we had regarded as so great and mighty–the Second International of Social-Democratic Parties had collapsed. This we knew, this we had seen with our own eyes. The press brought us detailed accounts of the position of the Socialist leaders in the German Reichstag and the French Chamber. Reports about those leaders who had been the particular heroes of the Socialist youth were very unclear. There were rumors, which unfortunately, were later to be confirmed, that Herve, the former leader of the revolutionary anti-militarists in France, had gone over to the camp of the social patriots and was issuing a war-mongering newspaper. Only vague reports about Liebknecht and his group came over the border from Germany in the first days and weeks of the war.

Despite the fact that we were internally solid and absolutely clear in our opposition to the war, that we spoke, wrote, and demonstrated against the war, we did not know by what methods and means the war really could be combatted. The way of our adult organization–the Social Democratic Party–was excluded. But there was still a complete absence of revolution- ray leaders who were educated in Marxism to point out the road to us. It is, therefore, not surprising that we established connections with a group which, like we, opposed the war, which was as shaken as we were by the collapse of the Social-Democratic movement, and sought to organize the struggle against the war with other methods than those used by the reformist socialist leaders.

Religious Socialists

We refer to the group of religious Socialists which were organized in Switzerland around Professor Ragaz, Mathieu, and Rev. Bader. This group was already quite active before the war and had connections with similar groups in other countries, particularly in Holland, where a strong movement existed and published several periodicals.

The leaders of the movement, particularly Ragaz, made sharp criticisms of capitalism, Social Democracy, and reformism. The speeches of Ragaz found a warm response from the workers and socialist youth of Zurich. We attended practically all meetings at which Ragaz spoke and organized our own meetings at which he was the main speaker. We also opened the columns of “Free Youth” to him and he contributed the lead article to the second number after the outbreak of the war, an article entitled, “Why has the Social Democracy failed?” This article, like his speeches, sought to settle accounts with the social patriots.

As a means of preventing similar catastrophes in the future, Ragaz glorified the “Socialist spirit, the Socialist soul, in all their depth, beauty, and might.” He believed that the war could be stopped through a higher development of the workers toward mutual aid and the capitalists toward a renunciation of their material possessions and in favor of the economic and political liberation of the proletariat. Ragaz did not only appeal to the wealthy to renounce their possessions but also appealed to the disinherited and poverty-stricken workers to renounce what earthly possessions they still might have. He preached the salvation from political oppression and exploitation through the love of one’s fellow man. He preached, “We will all have riches when we leave the devil and take to the path of God.”

It is quite evident that we, free-thinking youth, could not work long with this group of religious “Socialists.” The split became a reality when we established contact with the political groups in foreign countries and received from them an understanding of what the tasks of the revolutionary struggle against war were. The path which Karl Liebknecht had Laken in Berlin and which was proclaimed by the Italian Socialist youth was more acceptable to us than the sermons about love which were preached by Ragaz.

In addition to this, the war caused a number of political emigres to come to Switzerland from Germany, Russia, France, and other countries. Among them was Lenin, who came to Switzerland shortly after the outbreak of the war and moved, in February 1915, from Bern to Zurich. Along with Lenin came a group of Bolshevik party members like Zinoviev, and some people who worked with their group, like Karl Radek, Bronski, Chartinoff, and others. Leon Trotsky also came to Zurich in the autumn of 1914. I soon learned to know him personally during a trip From Zurich to Lausanne. His book, “The War and the II International” (published in America under the title of “Bolsheviki and World Peace”), which appeared about the same time, was eagerly. studied and discussed in our circles.

Revolutionary Books

These books soon cured us of the remnants of any social-religious thoughts. The lessons of Lenin’s Bolshevik pamphlets and articles were of extraordinary assistance to us working out a politically and theoretically clear program. We now recognized, even if not too clearly, that the war could only be liquidated by the proletarian revolution.

Our position on the anti-war and anti-militarist struggle became sharper. The Social Democratic Party of Switzerland held its congress in Bern on October 31st and November 1st. I took part in the proceedings as the representative of the Socialist Youth and travelled to Bern with Walter Stoeckers, who was staying in Switzerland at the time, and a number of other foreign comrades.

The Party congress came out decisively for national defense. There was not a single grouping that could carry through a fight on an internationalist, anti-patriotic, and anti-nationalist position. The representatives of the Party from the French-speaking sections of Switzerland, Naine and Graber, opposed rational defense, but not from a revolutionary internationalist position, but rather from the standpoint of a French patriotic opposition to Germany. The Party Congress decided to ask the Swiss National Assembly to demand the coordination of the efforts of all neutral powers to attempt to bring an end to the war. This illusory notion appears really naive and laughable when we remember it now.

Opposition Forms

The Party membership was hardly satisfied with the results of the congress. Opposition groups began to form everywhere. The group of Paul Pfluger, which stood for the defense of Switzerland un- der all circumstances, was defeated in Zurich. The centrist group of Grimm also failed to receive a majority here. A resolution sponsored by the grouping around Fritz Platten, the religious socialists, the youth, and similar tendencies was accepted. Although it did not yet say anything about communism, the resolution took an anti-patriotic position. The resolution took the position that the capitalists and proletarians did not have a common fatherland.

The youth organization carried on a sharp anti-patriotic propaganda and were everywhere in the van- guard in the struggle against national defense. We found that it was not sufficient to demand of the German, French and English Socialists that they vote against war credits and said: that which we demand of others we must do our- selves. We, therefore, demanded a clear rejection of every aspect of national defense in Switzerland. We raised a whole series of demands that concerned the conduct of the Social Democratic Party in our own country. In our organ, “Free Youth,” we carried on a sharp criticism of the army, published special numbers devoted to the many cases of mistreatment of soldiers in the army and the defense guards, and demanded the democratization of the army, a demand we still thought feasible at the time.

Congress Meets

The first congress of the Socialist Youth of Switzerland to meet after the war, which took place in Bern on Easter Day, 1915, was mainly concerned with the question of war, particularly national defense and anti-militarism. The Congress adopted the following resolution:

“The delegates of the Socialist Youth organization of Switzerland request the leadership of the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland to distribute in the immediate future a leaflet to the recruits and those now in active army service. The leaflet should put forth the demand of the Party program for a democratization of the army and a compilation of verdicts of the recent court martials.

“The Party leadership is also asked to have the Party press campaign more energetically along these lines than it has in the past and to ask the Party fraction in the National Assembly to fight for these aims.

“Should the Party leadership refuse to comply with these requests, the congress instructs the Central Committee of the Youth organization to take over the fulfillment of these tasks itself.”

This resolution appears today to be quite tame, but in the eyes of the Party leaders at the time, it appeared to be already uncompromisingly revolutionary. The most cheering section of the resolution was the resolve of the youth to carry out the tasks themselves if the “old ones” refused.

And the youth fulfilled their promise!

The collapse of the Second International automatically leads to a decisive collapse of the international relations of the Socialist Youth movement. These relations had never amounted to much more than a poorly functioning international correspondence. There never was a common political program on fundamental matters in the international youth movement. Common international actions were unknown to the movement. There was no instrument to bring about close international ties, like an international newspaper. All the efforts of the period of 1907 to 1914 were limited to publishing a miserable, little bulletin that appeared irregularly. The international secretary at the outbreak of the war was Robert Danneberg, at present (1928) a Social Democratic member of the Vienna City Council.

The international bureau of the youth movement took no position on the war, neither when it existed as an inevitable threat or after it broke out. Danneberg made Kautsky’s explanation its own, “The International is founded for the purposes of peace and not for wartime.” He proceeded to hang a black-bordered sign on the door of the office of the youth bureau in Vienna which read, “Temporarily closed on account of the war.”

Enthusiastic Youth

The International Bureau made no attempts in the months after the outbreak of the war to again build up the international ties between the various Socialist Youth movements. However, the desire and enthusiasm of the socialist youth organizations of the world to enter into relations and take part in an international exchange of views on the question of the war and the position of the Socialist Youth was very great.

We, of the Swiss movement, had established a series of direct contacts with other youth leagues in surrounding countries before the outbreak of war. My tour through Germany had resulted in a stream of mail from the various local groups that I had visited. The con- tact had never been broken with the central committee of the Italian youth organization and several local groups in Italy after our tour through that country in 1912.

In September, 1914 we began an intensive correspondence with the socialist youth of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Italy with the prospect in view of calling an international conference of proletarian youth organizations to again constitute a Youth International.

Approached Bureau

In agreement with the above mentioned youth movements, I, as secretary of the Swiss organization, approached the international bureau in Vienna on November 10, 1914 with the request that it summon an international conference no later than the spring of 1915. The international bureau responded with a post card that left nothing to be desired in its laconic brevity! It voiced inability to act on the matter.

The card said the following:

“W.G.! It is entirely impossible to state at this time whether a congress is possible in the spring of 1915. I cannot therefore take any position at this time in reference to your proposal. With greetings,

Dannenberg”

We now knew that it would be impossible to achieve an international discussion and conference through the medium of the bureau and we decided to call such a conference without the endorsement of the bureau. The exchange of correspondence with the international organizations became more intense and led to the agreement of a whole series of groups to participate in a conference in Bern, Switzerland on Easter of 1915.

French Youth

The French youth organization rejected our invitation with the explanation that the Socialist Party of France had not yet taken a position on international relations and that its own position would have to coincide with that of the party. The central committee of the Austrian youth movement greeted the conference with a letter. The central committee of the local party-sponsored youth leagues in Germany, headed by Fritz Ebert, rudely rejected the invitation and at the same time protested the convocation of the conference.

These youth groups, which were founded in 1909, as youth committees of the Party and trade union movements, were never a part of the Youth International. Despite this, we considered it our duty to invite them to the conference, particularly since their organ “Die Arbeiter-Jugend,” had taken an un-socialist and war-mongering position. When the well-known former radical and leader of the South German “Youth Guard,” Ludwig Frank, volunteered for military service at the outbreak of the war and fell early in the war on a French battlefield, his voluntary enlistment and death were hailed in “Die Arbeiter Jugend” as a heroic act and an example for the millions of young German workers.

Rejects Conference

“We will not participate in the international youth conference you have in view. The main point of that conference (i.e., the war- translator) does not revolve upon the youth organization for a decision, but is much more a matter for the Social Democratic parties to consider.”

These remarks were a gross presentation of the attitude toward the youth held by the Social Democratic “nurses to the youth movement.” It was the attitude that the proletarian youth at the age of seventeen was quite old enough to shed his blood on the battlefield, but was not old enough to concern himself with the question of fighting against the war.

Despite the blunt rejection by the social patriotic Central Committee of the German youth in Berlin and the reservations of the French youth leadership, the international conference met in Bern, Switzerland on Easter Day, 1915. The conference was attended by 14 delegates from Poland, Holland, Italy, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, Bulgaria, Germany, and Russia.

The German delegates participated in a conference with the international organizations for the first time since 1907. The call for the Bern conference had made a deep impression on the German youth movement. We received greetings via letter and telegram from many places in Germany, including Hamburg, Kiel, Erfurt, Dresden, Leipzig, and Berlin. Delegates from three local sections of the German organization succeeded in crossing the carefully guarded frontier and attending the conference in person.

Delegates of the Polish and Russian working-class movements also took part for the first time at Bern in the activities of the youth international. The Social Democratic Party of Russian Poland and Lithuania was represented by Dombrowski. The Central Committee of the Social Democratic Workers Party of Russia was represented by Comrades Inessa and Jegerow. Their credentials bore the signature of Lenin, who showed great interest in the conference and exercised a decisive influence upon it despite the fact that he did not attend personally.

International Conference

The international conference of socialist youth organizations that met in the People’s House in Bern on April 4, 1915 was the first publicly announced and publicly conducted international conference after the outbreak of the war. A few weeks previously, an international women’s conference had met in Bern under the leadership of Clara Zetkin. But its session were kept a secret and not announced until some time later when all the delegates had returned to their homes.

The opening session of the youth conference met in the great hall of the People’s House. It was a demonstration of the fundamental ideas of the revolutionary international socialist youth movement. In addition to the leading delegates, the speakers included Peter Grimm for the leading committee of the Swiss Social Democratic Party and Angelica Balabanoff for the Italian Social Democratic Party.

The first day’s session was taken up with reports from the delegates on the developments in their own organizations. Olaussen, reporting for Norway, stated that 16,000 members of the youth organization were building the kernel of the left wing in the Norwegian party. The left wing was fighting for a revolutionary program for the party and the trade unions.

Reports Strike

In Denmark the membership for the year 1915 was reported as 7,000. The Danish organization, at its recently completed congress, had voted to call for a military. strike if the government announced a mobilization.

Speaking for Holland, the delegate Luteraan reported that he represented a left wing youth organization and that they were waging a revolutionary struggle against the reformist organization on the issue of the war.

Comrade Inessa reported on the developments in Russia. Since it was impossible to have legal youth organizations under Czarism, they were working under the cover of dramatic groups, literary circles, and other such organizations. Many youth received heavy sentences for their activities against Czarism. The youth organizations of Russia were very different from those of Western Europe. Most of the activities were carried out in common with the adults. The working-class youth of Russia were as international now as before the war. The struggle for peace, against Czarism and capitalism was being continued undauntedly.

A further report on the Russian situation was given by the Menshevik delegate, Weiss.

The Polish delegate Jegerow reported that the youth movement of Poland stood on a program of uncompromising class struggle. They rejected the military strike, however, and stood for the continuation of a class struggle against capitalism that was clear about its goal.

The youth movement of Bulgaria was represented by Mineff. He spoke in the name of the left, revolutionary youth group which was affiliated to the Social Democratic Party of the Marxist tendency and waged a sharp struggle against the Young Workers organization, which was affiliated to the revisionist Social Democratic Party.

German Report

The first report on the struggle of the German youth groups against reformism was given by Stirner from Goppingen. He reported that not only the bourgeois organizations, but also the organizations of the working-class sought to enthuse the workers for the war. The organ of the youth committee of the Social Democratic Party, “Working Youth,” which had a big circulation, was full of articles defending a pro-war position. Many local groups raised sharp protests. In a number of places the youth refused to distribute the pro-war papers. The police measures against the proletarian youth had been sharpened.

Excluding the German and Russian delegations, the Bern Conference represented some 33,800 members of the Socialist youth movement.

At the beginning of the second session, a conflict arose with the Russian delegation. At previous congresses, each country received one vote for each 1,000 members. For obvious reasons, the same method of representation could not be adopted at Bern. A heated discussion ensued on the method of representation without any results As the majority of the conference decided to settle the matter by giving each country represented one vote the Bolshevik delegates left the conference in protest. Weiss, the Menshevik delegate, remained with a consultative vote. This conflict almost resulted in a break-up of the conference. After long negotiations with the Russian comrades an agreement was reached and they returned to the conference on the following day.

The main question before the Berne Youth Conference was “The War and the Attitude of the Social Democratic Parties and youth organizations.” The main report on this question was given by Robert Grimm, in the absence of the scheduled reporter, Wienkop. A resolution was presented on the question by Grimm, together with the Bureau and in collaboration with Comrade Angelica Balabanoff. Following a lively discussion that concerned itself most of all with the demand for total disarmament, the resolution was adopted unanimously in the absence of the Russian delegation.

The acceptance of this resolution was an important achievement for the Socialist youth movement.

For the first time in the history of the proletarian youth movement, representatives of the socialist youth came to an independent decision on a political question and recorded their views in documents.

Attack the War

The resolution of the Berne conference characterized the war as one of imperialist banditry and the result of capitalist politics and sharply attacked the lie of “defense of the fatherland.” It condemned the policy of class collaboration and civil peace. The Berne conference demanded of the working-class parties of all countries the execution of international resolutions that had pledged them to class struggle actions to bring an end to the war. The conference demanded of the socialist youth organizations an uncompromising struggle against war and militarism as the inevitable fruits of capitalist society.

At the beginning of the third session, a communication was read from the Russian comrades who had left the conference on the previous day in protest against the allotment of votes. Following an intense discussion, the conference decided to meet the wishes of the Russian comrades and arranged for an allotment of two votes for each country, with Poland being considered an independent country.

The Russian comrades accepted this arrangement and participated once more in the conference.

With the return of the Russian delegation, a new political discussion broke out between the conference majority and the Russian participants. The Russian comrades had worked out their own resolution on “War and the Tasks of the Socialist Youth Organizations” and motivated it in several lengthy discourses. They sharply criticised the resolution presented by the Bureau and accepted by the Conference on the previous day and demanded a decisive stand against the revisionists. “It is not enough to take a position against only this war, but rather against all wars of an imperialist character. Our resolution must state what means are to be used.”

Lenin’s Resolution

After a long and exhaustive discussion, the resolution of the Russian delegates was rejected by a vote of 13 to 3. Amendments to the resolution adopted on the previous day which were presented by the Russian delegates were likewise defeated by a 13 to 3 vote.

The resolution adopted by the conference majority had many inadequacies and weaknesses. It was, however, characteristic of Lenin’s keen political insight and wise tactics that he refused to withdraw the delegates of the Russian central committee from the conference despite the rejection of the Russian resolution and permitted them to continue in attendance and work along with the majority. Lenin correctly declared that the adopted resolution, despite all errors and shortcomings, still signified an essentially progressive step in comparison to previously adopted resolutions in the youth movement. The further development of the youth movement justified this view. A few months later, the leaders of the centrist group who held sway at the Berne Conference, Robert Grimm and Angelica Balabanoff, were completely defeated in the Youth International and the whole International continued the spirited struggle under the banner of Lenin.

The proposals of the Scandinavian and Swiss delegates to proclaim a demand for total disarmament in all countries was accepted by the Berne Conference of the Socialist Youth International by a vote of 9 to 5.

Upon a motion by the Dutch delegation, it was decided to organize an annual international anti-militarist youth day, to be simultaneously observed in all countries where Socialist Youth organizations were active.

The conference decided to raise a fund, called the “Liebknecht Fund,” to support anti-militarist activity and assist the victims of the struggle.

The organizational decisions of the conference were of decisive significance. They signified the complete break with the Vienna Bureau (pre-war leadership that had turned social patriotic-translator.) The provision for an inter- national youth secretariat, unanimously accepted by the conference, began with the sentence:

“The Socialist Youth organizations affiliated to the international center hereby establish a secretariat, which will provisionally be located in Switzerland.”

This provision relieved the Vienna Bureau of its functions and withdrew the mandate of office from Robert Danneberg, the international youth secretary to that date.

The accepted organizational regulations provided for a tight-knit organization with a common international periodical, with international financial support to the international youth secretariat, and a series of organizational tasks, that were regarded as a guarantee for the creation of an active and really functioning Socialist Youth movement.

Elect Munzenberg

The conference closed with the election of an international secretary, to which post I was elected, and the election of additional representatives in the international bureau as follows: Olaussen for Norway, Christiansen for Denmark, Notz for Germany, and Catanesi for Italy.

The Berne Conference signified a mighty step forward in the revolutionary development of the proletarian youth and in the creation of a fighting, centralized Socialist Youth International.

The resolutions and reports in which the happy achievements of the Berne Conference were recorded, were received with great enthusiasm by all the Socialist Youth organizations and by hundreds of thousands of young workers in all countries. The fact, that during the course of the war, at a time of wild social patriotic tumult and chauvinistic baiting, representatives of the Socialist Youth organizations assembled in an international conference and clearly and sharply proclaimed the revolutionary struggle against war, had the effect of sobering up the masses from the patriotic orgy and rapidly achieving a proletarian front against the war, above all, among the youth.

Challenge of Youth was the newspaper of the Young People’s Socialist League. The paper’s editorial history is as complicated as its parent organization’s. Published monthly in New York beginning in 1933 as ‘Challenge’ associated with the Socialist Party’s Militant group (the center/left of the party around Norman Thomas). Throughout the 30s it was under the control of the various factions of the YPSL. It changed its name to Challenge of Youth in 1935 and became an organ of Fourth Internationalists, leaving to become to the youth paper of the Socialist Workers Party in 1938. In the split of 1940, the paper like the majority of YPSL went with the state capitalists/bureaucratic collectivists to become the youth paper of the Workers Party.