A great read of U.S. social history. Ralph Winstead looks at the development of lumbering and the conditions of workers in the camps of the Pacific Northwest as well as the story of labor struggles that would make the area a battleground and become a stronghold of the I.W.W.

‘Evolution of Logging Conditions on the Northwest Coast’ by Ralph Winstead from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 2 No. 5. May, 1920.

In order to get the proper perspective of conditions on the Northwest Coast, where today the I.W.W. are waging one of their fiercest battles, one must understand the circumstances under which the chief industry of this community (The Lumber Industry) developed.

All during the earlier settlement of the coast lands of Washington the foundations for the gigantic lumber trust were being laid. Timber lands were being gobbled up and wholesale frauds, thefts and brutalities were perpetrated in order that individuals and companies should gain possession of the giant trees.

To understand the gobbling up process and the lack of resistance which organized robbery met with, it is necessary to be acquainted with the historical background of the labor and reform struggle which was waged in the early eighteen hundreds and to know what was the outcome of that struggle.

During and after the Revolutionary war, there was in the United States, a group of so called revolutionists that had a program which demanded liberty of opportunity to all, workers and property owners together. The chief fruits of the agitation which this group waged was some political reforms and the free school system, together with the purchase of Louisiana and the West and the inauguration of the “free land to settlers” program.

All this built up and supported the idea that every man had an equal chance at the good things of life, so the early settlers in Washington territory were firm believers in individual freedom — let the best man win and all the outworn and thread-bare formulas that are hurled at us by the reactionary capitalist organs of today.

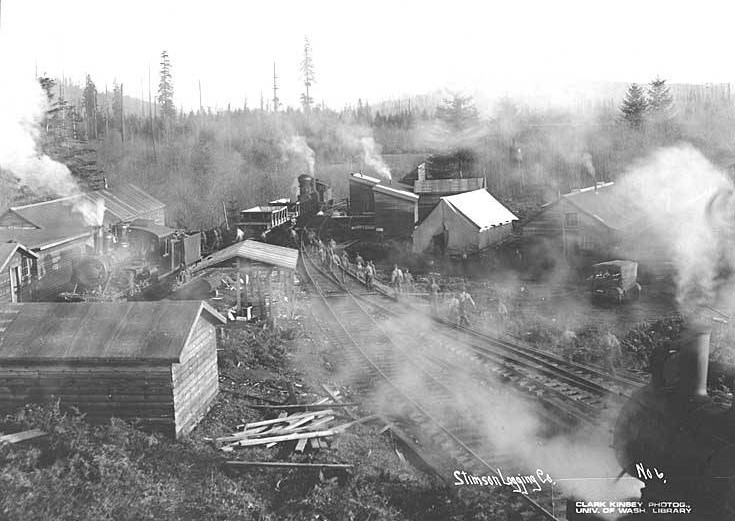

THE FIRST SAW MILLS

The first trading company was of course the iniquitous Hudson Bay outfit with posts and forts scattered along the coast and up the Columbia River. It was to supply these posts with lumber that the first sawmill was established on the Columbia a few miles above Old Fort Nisqually about 1846.

This same mill was later transferred to the Puget Sound district and was set up near Olympia on the Dechutes River. At best it was a crude affair run by water power yet it was a vast improvement over the old backbreaking whipsaw methods which were necessary before it was established.

The third mill was also on the Columbia and was established to furnish timbers for southern California trade. The advent of gold mining and the feverish rush to the California gold fields established a demand for timber and lumber and in 1850 to 1854 sawmills were established in many parts of the sound district. Among these mills was Yesler’s Seattle mill and the Commencement Bay mill near the site of Tacoma, Henderson Bay, Port Gamble, Port Madison and Steilacoom followed suit.

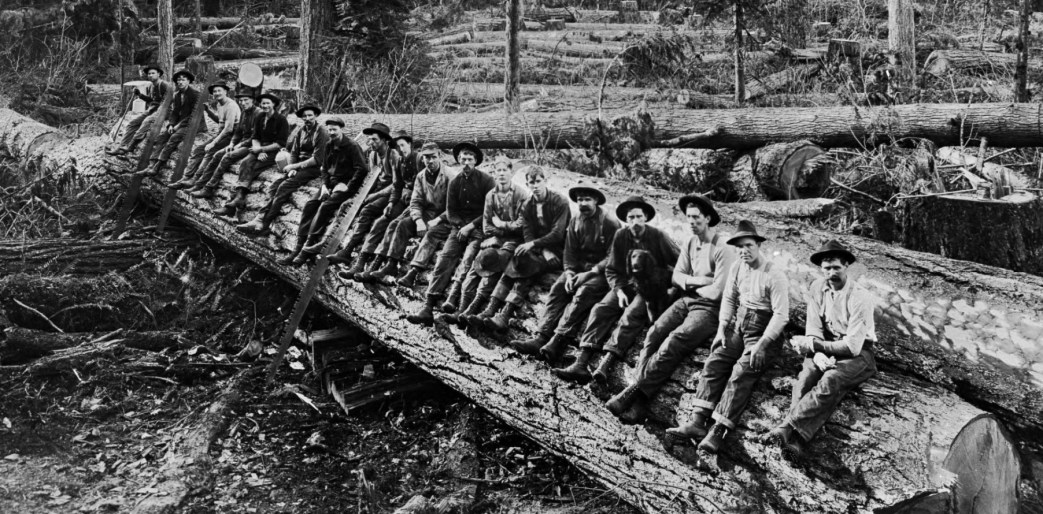

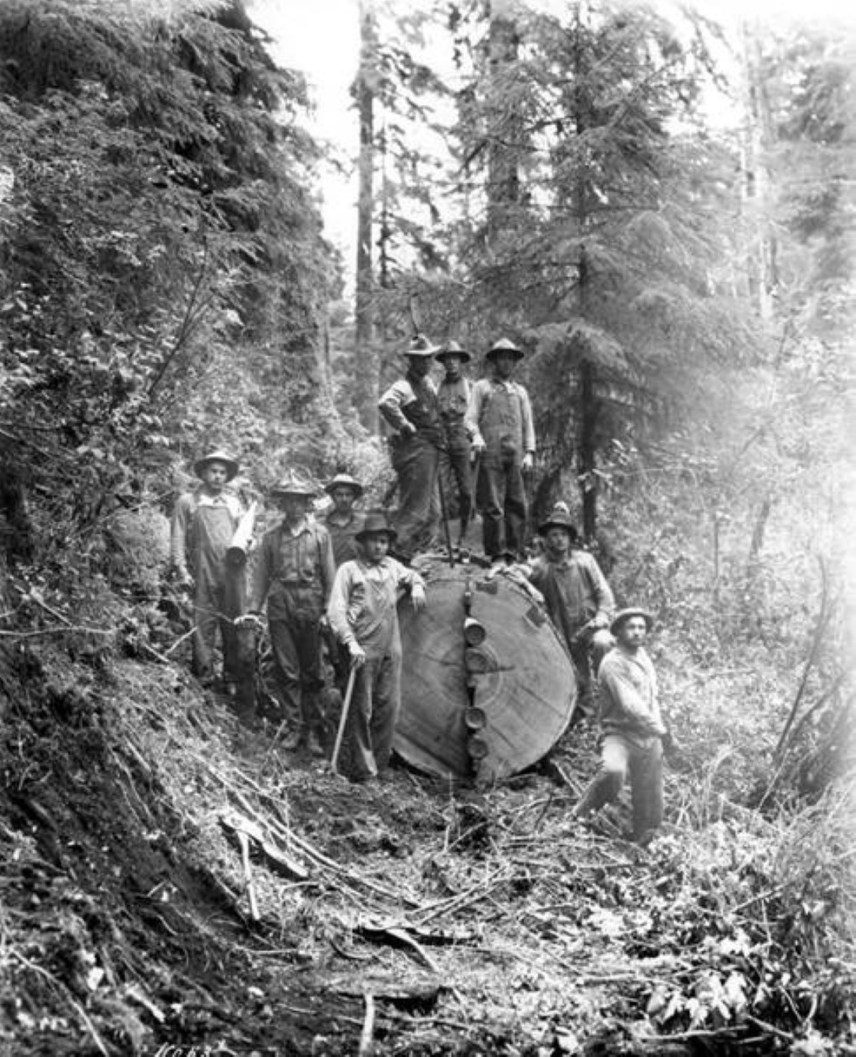

Logging operations in these early times were not distinct from the mill work as logs were fallen as close to the mill as they could be found. Mill-hands would help with the logging and the loggers would enter the mills and help the sawyers with their work. Everything was of the crudest. The axe was the only tool used in falling timber and oxen and skids furnished the transportation which got the logs to the water where they could be towed over to the mills.

Necessarily under these primitive conditions only the timber which was close to the water of Puget Sound had any value. The hillsides which were covered with giant trees right down to the water’s edge were the first to be assailed. Jack screws were used to roll the unweildy logs into the bays or into the skid roads where the oxen could get at them, and pull them down to the water.

CONDITIONS IN THE EARLY CAMPS

The conditions in the early camps were terrible. Twelve hours was the average work day and the accommodations for the men were of the worst. Big bunkhouses were provided, built of logs and poles. In the center of the room was the open fire built on the ground. An opening was left in the roof to allow the smoke to escape. Puncheon floors extended up to the “fireplace’, and ranged along the walls were the rough bunks with slab “springs”. Double bunks they were in most cases and often were three stories high. At the big center fire the cook prepared the meals and the men ate in the bunk house seated on the bench that ran around the edge of the bunks. On the rafters of the smoky building hung the dirty sweat stained garments of the loggers and the fire furnished the incinerator which consumed indiscriminately tobacco juice, food leftovers, and cast off clothing.

The Indians were largely exploited in these lumber camps. Robbed by the gin peddling thieves of the Hudson Bay Co. they fell easy victims to the slave drivers of the woods and mills. Whiskey was the golden goal which led the simple siwash to sweat 12 hours a day for an unnecessary master. So great were the indignities and brutalities heaped upon the suffering Indian population that at last they rose in revolt and a period of Indian wars called forth military protection for the exploiters and the women and children of the settlers. The tales of Indian atrocities was poured out in such volume that even yet one shudders to think of massacres and fiendish torturings which were attributed to the Indians at that time. Publicity faking is no new art to the labor exploiter.

SWINDLE—THE BASIS OF THE LUMBER BARON’S WEALTH

It was when it was seen that the lumber industry was to be a permanent thing that the timber grabbing commenced. Many methods were used both within the law and quite outside it. Among the legal methods used was the hoary one of timber and land grants to compensate for industrial development. For the act of building and operating a mill a company would-be given immense tracts of timber without any regulation of the operations by the giver whatever. Then timber land could be bought of the territorial government under what was known as the script law. Hundreds of thousands of acres were purchased by script so that this land actually changed hands for a few cents an acre. Timber claims could be located and by living on them for certain lengths of time titles could be acquired. Timber companies bought many of these claims after they were proved up on for a dollar or two per acre.

As these early lumber capitalists were not satisfied with the unlimited opportunities that lay within the law for the acquisition of timber lands, fraudulent methods were much more prevalent than legal processes. False entries was a favorite method of operation.

The timber agents would gather up the crew of some trader or schooner and march them up to the land office to register their claims. The specifications were furnished the sailors and all that they would do, would be to file their claims under the names furnished along with the specifications.

When the time came around for proving up, the agents of the company would gather up another group of floaters and, swearing to the conditions having been fulfilled, the second group would gain title to the land that was filed on by the first group, and of course all this land was transferred to the company that had engineered the deal. It was easy pickin’s for a cheap drunk. Anybody could get the price of a night’s carouse by staking—on paper a few hundred acres of timberland.

Then the acquisition of timber grants for supposed industrial development was a fruitful source of graft. Companies would promise to install an industrial plant in return for so much timber land and upon the receipt of title deeds a “plant” would be installed the total use of which in a productive way was nothing.

Again, private settlers, who had carefully lived up to the laws in regards to proving up their claims, often were stubborn when it was desired that they should sell to the “company”. Sometimes they wanted almost as much as the timber was worth for their land. Means had to be used to force them to sell and many a shack was torched and many a settler beaten in order to enlighten him as to the method of procedure in business.

A beneficent Federal Government decided to allow a transfer privilege on land grants. A company securing a few thousand acres of worthless desert land could then transfer their grant to the finest timber land on the coast, exchanging their worthless tract for timberland in this entirely legitimate gold brick scheme. School land frauds and grafts of a thousand kinds were the order of the day, and so the great natural resources of the section were gobbled by the wily few, in obedience to the dictum that each man had an equal chance “to rob,” and if he took it not that was his own fault.

EARLY LOGGING METHODS

During this period of land grabbing some important changes took place in logging methods and in the conditions surrounding the logger. Naturally the timber surrounding the mills was soon cut as was that which could be fallen into the water. Transportation of the big logs became a problem that was solved but slowly.

The skid road of a few hundred yards was used and the “Bull Puncher” with his goad made his appearance. Logs were cut and “geed’’ into the skidroads where they were hauled down to the water by long strings of oxen or bulls. The banks of the streams were logged as well as the inner borders of the lakes and the Sound.

A story is told of two men of this period who met and were discussing their status:

“What yuh doin’ Bill?”

“Punchin’ a road full o’ bulls.”

“How many yuh got?”

“Dunno. When I unyoke ’em at night I stack up seven cords of yoke!’’

It was not long before donkey engines were introduced to pull the logs down the skid roads and the oxen were used to get the logs into the skid ways. Falling saws were introduced in the seventies and eighties and became universally used.

In the mean time some change had occurred in the accommodations which were afforded the men. Bunk houses were built out of lumber not because of the greater comfort to the men but because it was a cheaper and quicker method of construction. Separate cook houses were installed and stoves made their appearance. Each improvement was put in solely because it proved more economical to the owners. The men carried their own blankets. In most cases they had to rustle their own mattresses and the spruce twig bed was much in evidence. Bunking accommodations and hours of labor remained as before, and the lot of a logger was so low that they were looked upon as unworthy the friendship of “civilized” human beings.

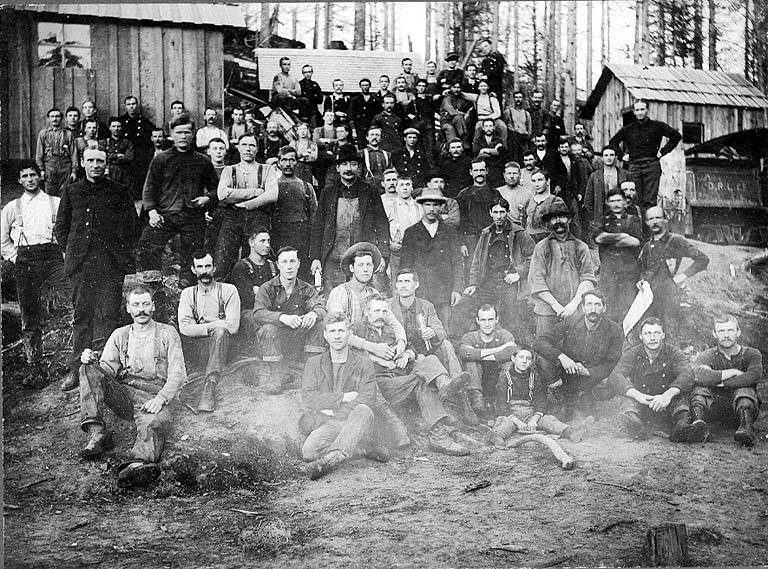

The earliest lumber workers had been the settler and the siwash, but with the securing of a permanent position as an industry a new element was introduced into the woods. The mental attitude of the first workers had been easy to grasp. The settler wanted to earn a few dollars to enable him to buy provisions and tools so that he might clear up his land. Then he would leave the woods forever. He had no interest in improving the conditions under which he worked. The siwash wanted a few dollars for whiskey and the beastly conditions under which he lived were never drawn to his attention. He knew no better. His only panacea was in the bottle.

The new woodsmen were loggers from the east. State of Mainers, sprinkled with men from Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, formed the nucleus of the new force. Yet these men also seemed to have no energy left for the fight for better conditions. Some of them, coming from families of loggers and others having followed the occupation for years, they had developed a peculiar psychology which was an adaptation of the prevalent way of looking at things.

The inherent right of each individual to take advantage of circumstances as they came to him was the dominant note. Individualism kept the loggers apart, and since education and intelligent knowledge of their position was not their property, their emulation and their respect was given to the man who was the physical superior. The camp bully got the best of things and many a wild tale of personal battles and individual combat can be told of the old time woodsmen.

The burley logger, skillful in his strength, was looked up to by his fellows and all the energy which might have been used to betterment of social conditions was expended in the seeking of personal gain or privilege.

Conditions remained in the same primitive state with individual animosities taking the place of class conscious action thru many stages of the mechanical development of the industry. The ox was replaced by the donkey or cable system. Newer and better methods were introduced and together with the speed up system the productivity of the men was in some instances made ten or twelve times the original amount. Yet the same slavery and lack of understanding existed amongst the workers. Hopeless periodical drunks as many of them were, they could see no remedy for the perverted hopeless lives that they eked out. Timber beasts — slough hogs — they even gloried in the reputation which they had for bestiality.

CHANGE IN INDUSTRIAL CONDITIONS

In the meantime important changes had taken place in the ranks of the different companies that were the exploiters of these slaves of circumstance. They had warred upon each other in the “free competitive system” which had been announced as freedom’s herald. Price cutting — rebate wars etc., had proven ruinous to the operators, and they became convinced that their mutual salvation lay in combining into some form of. Association so that they might act together for each others’ benefit rather than help to destroy each other. The One Big Union of the Lumber Bosses was the outcome, and the Lumbermens Association has played a tremendous part in the social development of the district, from the moment of its inception.

Like all its fellows, this organization is for the purpose of capitalistic sabotage — the conscious withdrawal of efficiency from the field of production for the purpose of gain. They controlled the output of timber — and have also tried to control the importation of ideas into the heads of the loggers who are in their employ. The Lumber Trust became the dominating figure in local and National politics, as played by the district. With their henchmen in all the high places, they with their tremendous start of organization seemed to be entrenched in an impregnable position. The only attempt made to challenge their power was made by those same lowly, despised workers. They, too, became awakened to their true position in society and threw off the enslaving fiction that the individual could achieve freedom at the expense of his fellow and joined hands in the only organization that has attempted battle with the Lumber Trust and lived.

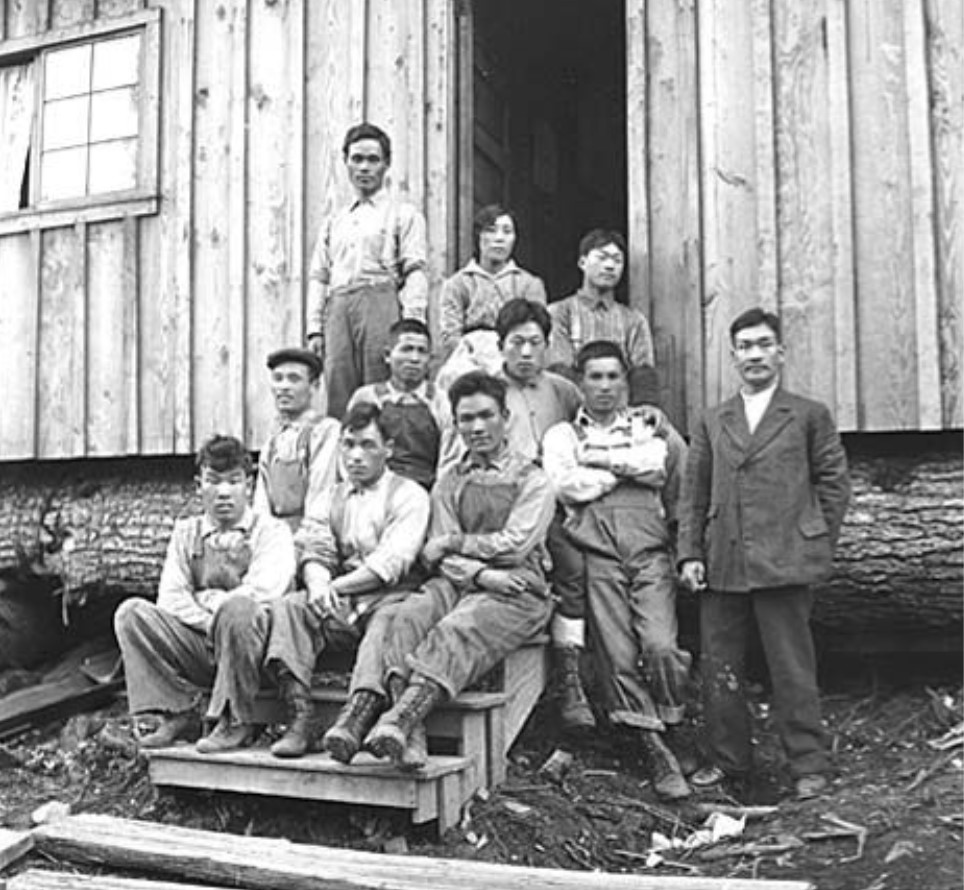

During the introduction and adaptation of machinery to the logging woods, new types of men were introduced into the bunk houses and cook shacks of the “Barony”. Foreigners came to take the places that the native born refused. The rangy Scandinavian, the swarthy Italian and the stocky Slav drifted into the comradeship of misery that was of the woods…Some of them brought with them strange ideas of social ideas of social consciousness—of class distinction, of loyalty to their fellow workers. But this way of looking at things had little effect on the customs of the individual logger.

The camp bully still was to be found, and individual] privilege was still the way up for the mass. It is hard to describe such an intangible thing as this generally accepted attitude of mind; yet it is in the development of a different psychology that the I.W.W. has performed its greatest work. Without a different view point no change for permanent benefit would be possible. In fact better camp conditions could not have been given to the men by charitable employers without the men first achieving the new psychology of solidarity and social help.

THE FIRST “IMPROVEMENTS” IN THE LOGGING CAMPS

As an example of the social apathy which held the logger in its grip one could give numerous instances, but one or two will suffice to show the dearth of social feeling and appreciation which the I.W.W. had to combat with their philosophy of solidarity and with their economic theories of workers’ control.

The Whitney Logging Co., a new concern, started operations in the fall of 1910 at Blind Slough, Ore. They decided to establish a camp at least bearable for human beings. A steam heated bunk house, a dry room with racks and lines so that the men could hang their sweaty, steaming garments in some other place than their sleeping quarters to dry, a toilet with regular toilet bowls and flushtanks,—these were some of the improvements that the hated wobblies have since fought for and secured.

The steam heat was a mechanical failure. The radiators were removed and the big stove was installed in the center of the room again. The workers coming in at night would hang their damp clothes in the dry house. Some physical hulk entering the dry room would find the clothes of another worker hanging close to the stove. With a callousness that it is hard to understand he would jerk the offending garment from the desirable place and hurl it into a corner. Not once did this occur but many times. It became impossible to leave clothes in the dry house with any certainty that they would be dried. The men took to hanging them in their sleeping quarters where they could be watched. Soon the dry house fire was discontinued—the men had failed to take advantage of it.

Some individuals either out of spite or ignorance failed to use the toilets properly. By standing on the seats the toilets were befouled beyond possibility of proper use. They were all torn out. Inside of nine months the company was running its camp on the same barbaric system that was prevalent elsewhere. The men had no conception of anything better.

Much of the change which has taken place can be accounted for by prohibition. Not that it is impossible to secure liquor, for bootleggers have ever plied their trade surreptitiously, but with the doing away of the saloons the social centers of vice were destroyed, and the worker was not compelled to patronize the bars in order to mingle with his fellows. Booze was a sedative that deadened the pain and discontent of the worker with his surroundings, and with the elimination of that sedative the workers individually voiced their disapproval of conditions. It was prohibition that paved the way for the social teachings of the I.W.W.

Under the prevalent way of looking at the questions of life from an individualistic point of view, everyone was tinged with self-forwardness and a lack of appreciation of action along lines of class welfare. The logger had few of the ties which other workers have which bind them to society and impose a social vision, even tho a limited one, on the individualistic way of looking at things.

The man with the family ties which nature deems necessary for both individual and social development is forced to soften his views of individual action to some extent and submerge his personal tastes in that of his family group. The loggers were nearly every one cheated out of all possibility of a wedded life. Each lived for himself alone. Living in camps, segregated from women, they developed many abnormalities that were caused by the thwarting of a natural sex instinct. Their sense of social responsibility was almost absent, and because their sole intercourse with women was thru the medium of the prostitute much of their conception of sex became a foul perverted thing, and as a class they were unable to appreciate woman as a social companion. It was the conditions forced on them by the lumber baron’s greed that was responsible for every abnormal development in the lives of the loggers. Every natural instinct and desire was repressed and thwarted and in individuals the result was only what was to be expected. As a group also the workers obeyed the laws of psychology, and when their repressed social tendencies were given a chance to express themselves in the I.W.W. they seized the opportunity and developed a sense of solidarity and class consciousness that all the murderous persecution of the Lumber Trust has not shaken.

ENTER THE I.W.W.

Almost from the inception of the I.W.W. there were attempts made to organize the woodsmen of the northwest coast. All those great speakers who in the early days of the organization were active in the work toured the cities of the region and spoke from platforms to crowded houses. The effect on the logger was apparently negligible, and as soon as the intellectuals above mentioned became tired of the struggle, public interest waned to a great extent.

Some of the workers had been aroused by the new organization, and headquarters were maintained in the biggest towns for periods of time. From these headquarters soap boxers made their appearance on the street corners, haranguing the idlers and out-of-works that might stop to listen to them. Soap box talks and platform speeches were of little actual benefit to the organization when it came to building up an Industrial Union.

Those who listened to the talk were in most cases men who at the time were not workers themselves. However they would be in a state of mind to receive the teachings of the speaker because being out of work and consequently suffering a lack of some of the necessities of life, the revolutionary and denunciatory utterances would fit in with their feelings and experiences. Once on the job, however, the erstwhile rebel forgot the sentiments of the soapboxer in the daily round of his toil. It was only when groups of these discontented ones appeared on the same job that the I.W.W. seemed to have any relation to the job at all.

It is hard to say just what effect all this teaching and agitating did have on the minds of the woodsmen. The organization could be called nothing more than a propaganda league propagandizing for Industrial Unionism. Soap boxers dealt their arguments to the crowds and individual propagandists would urge the men with whom they came in contact to take out cards in the organization and study its principles.

As early as 1912 there were many I.W.W. members working in the woods and there had been a lumber workers local (No. 432) since 1911. In 1912 an industrial strike was called by the I.W.W. While there was some response to this call, in no sense could the industry be called generally affected. Agitation was carried on amongst the loggers by individual members continually and there is little doubt that this agitation was a great factor in preparing the mass of the workers for a change in ideals and a successful membership drive.

The hardship imposed on these early apostles of a new system were appalling. Year after year they labored on, seeming to make little progress, yet ever persisting in their self-appointed task. Estranged intellectually from any sympathy with the prevalent mode of looking at things—always by their ideals forced to take a view of things essentially at variance with the popular one—the mental strain was a terrific one. Only the strongest and most stubborn-minded could pass thru the conflict and still maintain their integrity of purpose and the ability to withstand the social onslaughts. Out of very necessity they banded closely together, closing out of their circle the uncomprehending believer in “things as they are.” Although scattered widely, yet they maintained their association and from coast to coast they knew each other by name and nick name. The meeting of two of a kind brought out a vast amount of news of this one and that one—the wild fights, the struggles, the apostasies, the injustices, were handed about on paper and by word of mouth so that this isolated band maintained their uniformity of development and psychology.

Blacklisted, terrorized and socially outcast, victims of law-and-order thugs, they knit the organization more closely together, and from their manifold experiences they developed a psychology of their own that was truly a structure of the new within the shell of the old. Their method of looking at things was essentially social. Solidarity was no philosophical abstraction—it was part of their daily lives. Direct action was not merely a theory—they had to practice it in order to maintain their existence. From the very force of circumstances the I.W.W. became a sentient social thing, practicing in their very life and death struggles the abstract theories that had called them into being.

So it was that when the new tactics of the organization were put into effect there was something tangible to initiate the new members into. There was an ideology clear cut and well defined, a literature expounding the social theories that they advocated and a history of battles won and lost.

The new tactics were first developed in that industry which has been the pioneer in the labor battles in many countries—the agricultural industry. The despised harvest workers evolved the plan of Job Delegates and district organization, that was later adopted by all the organization and adapted to their own needs. It was in 1915 that the Agricultural Workers Industrial Union No. 400 started the new system. Its success in transferring action onto the job was so phenomenal, and the growth and development of the organization so satisfactory, that the drifting of delegates into other quarters, and the general realization of the efficiency of the new methods, caused the Lumber Workers to reorganize along the same lines and send out Job Delegates also.

In the fall of 1916 the first job delegates entered the woods and almost at once the organization leaped forward into sturdy growth. Into the unspeakable conditions of the logging camps entered the delegate armed with credentials, supplies, and literature. He carried with him his knowledge of the struggles that had been waged and that indefinable something which we have presented as the ideology of the movement.

The times and conditions were favorable to his appearance and purpose. The logging industry was just recovering from the stagnation that had prevailed thruout the country prior to the war in Europe. The workers had not forgotten their experiences on the bread lines and in the jungles. They well understood the class struggle for they had been made to see it. Conditions in the woods were deplorable. The same bunk houses that had sheltered the logger for thirty years were provided for his habitation. The speed-up system was at its height, and the employment shark was waging his war on the incomes of the men. Prohibition had deprived the workers of their sedative—they had to face the facts as they were. The field was ripe for the harvest and the job delegate was driving the reaper.

Coming into the bunk-houses of the camp he was accepted as a fellow worker by the inmates. He had ample opportunity to join in the conversations and discussions which are the chief pastime of the logger off duty. It was easy to guide the conversations into channels from which it was but a step to the discussion of industrial unionism. When two and three old members could be on the same job it did not take long before the whole camp accepted the viewpoint of the industrialists. Put to innumerable tests, it was found that the delegates and the plain members were ever ready to live up to the doctrines that they taught.

The life in the camps is not a life of individual segregation. There is no ability to hide oneself away or to shut out the personality of another. The job delegate having a mission easily dominated the thought of the hitherto unthinking aggregation. He crystallized the dissatisfaction with conditions into a revolt against the entire capitalist system which was shown to be responsible for the conditions. He taught sociology and impressed on the workers the new vision—the social vision. Solidarity was his watchword and solidarity was developed in the erstwhile individualistic logger. Having a complete ideology well defined with an explanatory literature and a history of daring deeds, the enquirers into the philosophy and purpose, structure and action of the I.W.W. soon found themselves part and parcel of the movement that was sweeping across the woodlands.

Thousands took out cards in the organization, read its literature and adopted its viewpoint. At once the things that could be enjoyed: together bythe workers seemed the most desirable to have. Better conditions, a dry-house, a bath-house, sheets and pillows, spring beds, everything that. made for comfort and cleanliness, was desired by men who but a short time before had given little thought to anything except debauchery and individual advantage.

It is not a miracle of salvation that the I.W.W. wrought in the loggers. In the minds of the men had always been those natural instincts and desires which demanded social exercise, but these instincts had been repressed and perverted by the environment and the teachings which capitalism had forced upon them. Perhaps it was because of that very excess of repression that when a medium of expression was found the wave of response was so overwhelming.

At any rate wherever the membership of the I.W.W. has set foot in the logging woods there springs up a new feeling—a new attitude towards not only the boss but towards all the salient factors of life. To one who glances superficially at the class-conscious development which has taken place, it seems but an accentuation of dissatisfaction with the conduct of the Lumber Barons and their henchmen. It goes far deeper than this. The very atmosphere is different in a camp where the wobblies have a foothold.

Even after the great industrial strike which was ‘carried to the job and won by direct job action there were many points where the influence of the organization was scarcely felt. Especially is this true in Southwestern Washington—the scene of the Centralia outrage and the Montesano trial.

One of Paulsens outfits, in the Grays Harbor country—all of which was affected by the strike but not necessarily by the dissemination of ideas and the recruiting of a persistent membership— had installed some of the things which the I.W.W. had demanded. They had bunk house cars, well lighted and ventilated, with a dry room built in one end so that the occupants of the car could hang up their damp clothes of an evening, and have them dry in the morning. By using the dry-house the purity of air that is so essential in a decent sleeping quarter could have been maintained.

There were no members of the I.W.W. in the camp. One new member, himself but ill-versed in the fighting principles of the organization went out to work in the camp. He found the men utterly unable to utilize the betterment of conditions. Instead of putting their clothes in the dry house—so handy and convenient—they hung them over the stove in the bunk house proper. They were unable to agree about the ventilators and because some of the men had a superstitious horror of fresh air, they all slept without ventilation and breathed the foul impurities from devitalized air and drying clothes.

The company had agreed to furnish bedding (at so much per of course) so that the crowning humiliation of a loggers life—his blanket roll—might be lifted from his back. But these unenlightened individualists still packed, and slept in, their own ragged and unclean blankets rather than pay the nominal sum which the company would charge for bedding and clean sheets.

The lone wobbly remonstrated in vain with his bunkmates. Not having been long in the organization he failed to know the many ways which are used by the delegates to bring recalcitrant fellow workers to time. When he was told to mind his own business, he left such fools to their folly and hired out to some camp where he knew that he would find men of his own kind.

The great contribution of the I.W.W. to the logger has been not so much in the improved conditions, much as those conditions were needed and appreciated in most quarters, but in the new psychology which insured general use of improvements. A psychology which has grown to stalwart proportions in the few years that have elapsed since the Job Delegate entered the field. This new social viewpoint is spread broadcast throughout the logging woods, and no matter what happens to the machinery of organization by which this ideology finds expression, the I.W.W. cannot be destroyed for they have developed a social soul or spirit that is indestructible.

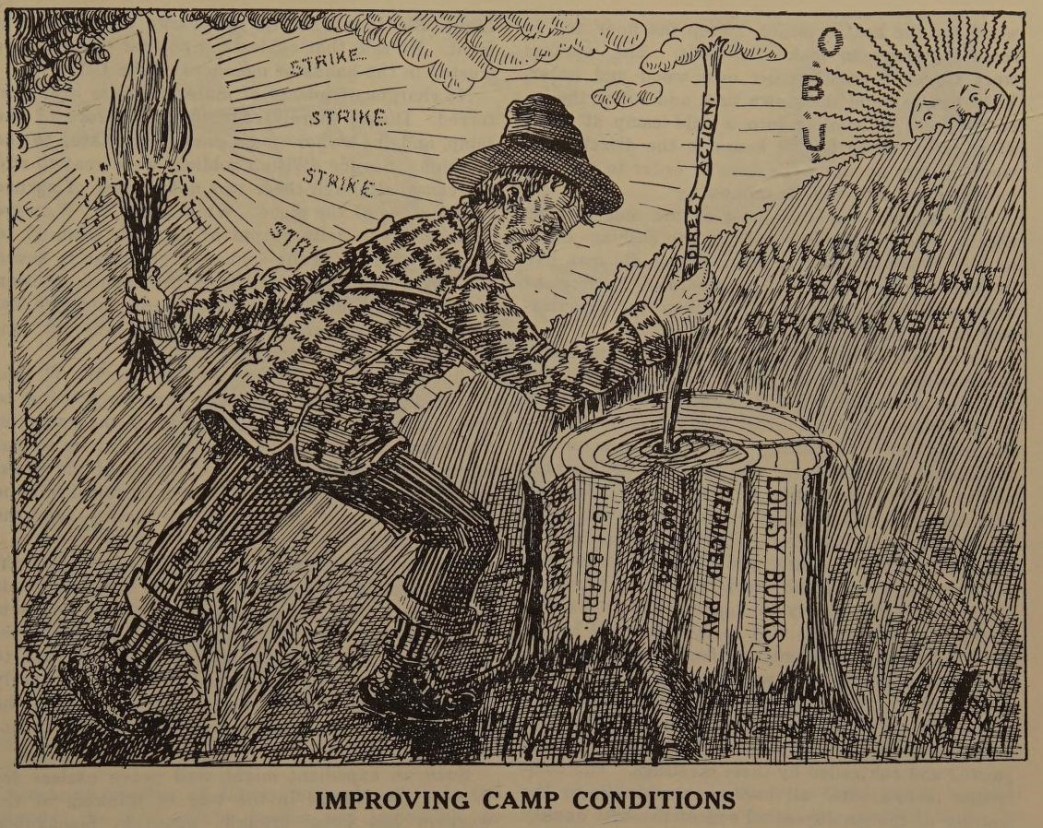

Job action was the great weapon that forced the Lumber Barons to grant the eight hour day, to furnish blankets, to improve accommodations and put up better food. Much has been said in a general way about this form of direct action and seemingly little else than generalities can be presented. In every camp where the membership of the I.W.W. were represented a struggle was carried on and in many cases is still being carried on. The struggle varies in each camp both as to methods and results. There has been no strategic genius who sat back in some easy office chair and dictated the moves to be made or gave orders as to when strikes were to be pulled or how. There were no individuals who were responsible for a greater share in the movement than hundreds or even thousands of. others. Each difficulty was met and fought by the men on the jobs and no general plan was observed in the fighting of the different battles. Action was spontaneous and it was social. There is no literature of achievements, yet in the mind of each battler there remains his stock of stories and his experience which can be called on at any time in the future for the benefit of the next group of fellow workers that he happens to be a member of. There are no outstanding heroes, yet each member realizes that to some extent he himself is the partaker in the greatest deeds. A social, many-bodied hero has arisen to fight the loggers’ battles. ‘It is the I.W.W. Improvements Brought About by the I.W.W. The individual bully has disappeared from the bunk house. Should any person, no matter how much personal prowess he had, endeavor to override the accepted rules laid down by the group, that person would receive either a mental or physical punishment that would forever teach him respect for the rights of others. Such action is distasteful, but after the administration of punishment once, it seldom needs to be repeated. Bullies have disappeared. They themselves have absorbed the new viewpoint and are most meticulous in the observation of rules or customs for the general welfare.

With the henchmen of the Lumber Barons the fight has been more severe. Personal subjection was not a matter of brute force in most cases even where it was desirable to try it. With the violent bullying boss other methods were used besides a brute beating. Pulled camps, inefficient work, and intermittent strikes were used as the occasion warranted but, whatever the method used, the Bull of the Woods is not the absolute master that he once was. Many foremen have welcomed the change in relationship and try to work in harmony with the men, but whether they do or not, there is no longer brutality on the part of the foremen or superintendents where the I.W.W. works or has a say.

In the olden days a man obeyed the dictates of the foremen or went “down the line.” On stormy, windy days, when it would be dangerous in the tall timber, where a broken flying limb or a snapped off top might mean instant death to the worker, the foremen or went “down the line.’”’ One stormy, out or roll up.”’ The weather was not considered when the logs were needed—nor the men. Today the “roll out or roll up” is relegated to. history. When the storms rage the foreman’s urge to work is usually limited to a few half hearted pulls on the whistle cord and, if there is no response, it is known that there will be no work that day. The workers seated around the stove in the bunk houses smile grimly at their master’s voice—and turn to things more interesting.

Not only have conditions of subservience changed but the betterment of physical surroundings has been vastly improved in nearly every instance. Before the advent of the Red Card, bunk houses were often built with double bunks three high around the walls. Six men would sleep two by two above each other in the space where normally there should be but one. Once the ubiquitous louse was introduced he remained as master. Bed bugs were not counted. They did not bite till the victim was asleep. Consequently the havoc that they raised was as nothing compared to their more active fellow insects.

In nearly all cases bunk houses were built with wooden bunks two deep and it was at the price of eternal vigilance that freedom from insects was ever secured. In many camps, prior to the early organization work, there was no bull-cook furnished. The duties of the bull cook are to carry and splitwood for the heating stove, sweep the floor and in some instances to make the beds. The workers were forced to rustle their own wood and water. They had to build their own fires and suffer the inconvenience of coming into a cold camp at night after from ten to twelve hours in the drizzle, and would scurry about in the dark in order to find the means to warmth and cleanliness.

Payment was made to most of the men in time checks which were discounted in the cashing, often as high as twenty-five per cent. Never did man live in such hopeless physical and mental discomfort as these workers were forced to prior to the organization of the Lumber Workers Union.

As to conditions of work which were established. in some instances where the I.W.W. secured control, Danahers Camp can be cited. The conditions in this place caused a great deal of dissention in the organization, because it was made into such a workhouse by members who desired to test the ability of the organization to carry on industry and who desire to maintain job control at a time when the organization was being persecuted by all the legal machinery of state, and hounded by tar and feather gangs and lynch mobs from coast to coast. Nevertheless the ability to improve conditions was amply demonstrated as well as the ability of Industrial Unionism to efficiently manage industry.

Complete job control was secured in this camp late in 1917. About 150 men were at work in the place and every man carried a red card. Job meetings were held regularly and a job committee was elected and controlled by these meetings. The committee looked after all matters pertaining to the welfare of the employees. Food of the best quality was served. Bunk houses were kept scrupulously clean, and single beds with clean sheets and bedding were furnished to the men. The work-day was eight hours.

If a man shipped up and was found to be inefficient at the job he was hired for, the committee took up his case and placed him on some work that he could do. All men were hired from the I.W.W hall in Seattle and the labor turnover was less than in any like camp under non-union conditions.

The men built a recreation hall on the grounds and this hall was under the control of the I.W.W. committee. A piano was procured and regular musical entertainments and dances were held. The hall was used for a reading room and for educational purposes generally. Debates on current topics and organization work together with regular business meetings taxed the hall to capacity.

THE REIGN OF TERROR IN THE WOODS

It was in June of 1918 that this condition of things came to an end. The autocrat of the woods, one Col. Disque, Commandant of the Spruce Division, sent soldiers of the U.S. army into the camp and broke things up. The hall was used to camp in by the soldiers and every logger was forced to flee for fear of imprisonment. Many were captured and held as military prisoners for some time. The only excuse for this high-handed outrage was given by Lieut. Bickford who was in charge of the detachment. He said that cables and powder could not be trusted in the hands of members of the I.W.W.

No charges of misuse of materials were ever preferred. Disque merely ordered the capture of the camp, and the owner was a passive spectator to the invasion. Spruce division soldiers were sent to run the camp, although there was not a stick of spruce within miles of the place. While the I.W.W. were on the job the daily output of logs was from 17 to 20 cars, while with the soldiers from three to seven cars were produced. Many of the spruce division privates had been members of the organization before they were drafted but militarism was not conducive to successful production.

Since that time, whenever the I.W.W. has achieved job control there has been no attempt to build halls or improve the property of the owner in any way. The policy of forcing the owners to put up these improvements for the benefit of the workers has been adopted and efficiency or self-discipline has never been demonstrated again—for the master’s profit.

The change in conditions which has been brought about by the advent of the I.W.W. into the woods can be seen by a comparison between the two sets of conditions. In many places all the improvements ‘have not been established, but it is safe to say that they will be established and will be properly used unless a willful Government undertakes the Herculean task of deporting every I.W.W. to another continent.

Such an expedient might well prove useless for in part the change in the way of thinking of the workers has been brought about by mechanical changes in the methods of production. The first loggers were men of skill and personal prowess. The output of logs depended upon the skill and strength of the individual loggers because the work was mostly all hand work. Today logging is a mechanical industry. A knowledge of stresses and strains and other engineering phenomena together with knowledge of how to take advantage of these forces is the determining factor in getting out the logs. Individual prowess is of little concern. Reasoning from cause to effect and the habits of such reasoning are factors in arousing the worker to his own position in society and in developing the social viewpoint. An entirely new set of workers would in time develop the same ability to think straight that is now the property of the “wobbly” logger.

PRESENT STRUGGLES

Methods in use at present in order to enforce the demands for new and better conditions in those places which have not yet come up to standard are varied. All during the summer of 1919 the system of pulling camps was in vogue. Demands were presented to the boss and, when he refused to consider them, all the militant workers on the job would go to town. There are a number of drawbacks to constant attempts of this kind. To some extent it is a hindrance to organization work, for with the increasing number of family men who work in the woods, the fly-by-night tactics are impossible to follow. Such men are kept from the organization. And men who prefer to work steadily are put in the same position. Militant members are kept on the hike and financially broken. By working in many camps the face of the rebel becomes generally known and blacklist enforcement is made easier. Then the scissor who refuses to leave the struck job stays and gets the benefit of any better conditions that may be won by the strike and is given the pick of the work when a new crew of wobblies comes to carry on the agitation.

At the same time, pulling camps has been of great benefit in regards conditions. Bosses are not so apt to fire a delegate when the camp has been pulled a few times because of such action. Conditions are as a rule improved considerably after a pulling and in nearly every case the companies, when building new camps, lay them out in approved, up-to-date style.

The present status of logging conditions is one of general transition. Others less modern are gradually being brought up to the level of the best ones, and educational work has little chance with a constantly changing crew. The eight hour day has been firmly established, in the battle with the masters, to secure abolition of piece work, victory has not always attended the efforts of the workers. Food is uniformly good. When not good the roar of rebellion is so spontaneous that it soon becomes good. Booze images have disappeared from the logger’s mind. The exciting battles he has fought, and the vicious attacks he has been called upon to face, have wiped the boozefighting psychology from most brains. To call one a bartender is an epithet not cherished. Many camps have been made fit habitations for women and the cook houses are often run by the fair sex. Sex segregation is no longer so severe, and when the logger is in town he associates with women—of a different caliber than he formerly met. In some instances he finds women fellow workers fighting for the O.B.U. though as yet women are slow to take up the battle.

The social conscience has become the dominant factor in life in the places where the wobbly has entered. His self-respect, and the respect of all. who know him as an individual, accentuates and develops his usefulness to himself and to others. The I.W.W. logger reads—not the sickly sentimental trash of the sensual bourgeoisie, but clean classic fiction, as well as articles on political, philosophical and economic subjects written by his fellow workers and the best writers of the world. Because magazines of unquestionable artistic taste have espoused his cause he reads and studies the poetry and the pictures that are portrayed in such periodicals. Besides his own organization publishes papers and periodicals edited on scientific lines.

In mental IIfe the average logger has had a resurrection in the last decade. His whole being has grown and developed in the struggle which he has been waging. Not alone does he see the few cents more pay that he has been able to force out of the Lumber Barons, nor alone the physical comforts that he was so long deprived of. His vision goes far on to the destiny of the whole working class which is the abolition of wage slavery and the capitalist system. He sees the introduction of Industrial Democracy.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/one-big-union-monthly_1920-05_2_5/one-big-union-monthly_1920-05_2_5.pdf