A wonderful look at Paris’ revolutionary taxi drivers.

‘The Red Chauffeurs of Paris’ by Ida Treat from New Masses. Vol. 3 No. 2. June, 1927.

FORTY years a militant. The union, the old socialist party, — I never believed in ‘pure syndicalism and no politics’ — and now I’m with the communists and the C.G.T.U. Always kept in line. Forty years — that’s before you were born, Marcel.”

The big restaurant-keeper grinned, patted his uncle affectionately on the shoulder.

“A great old boy, he’s got the faith all right,” he announced to the group of Pads chauffeurs. “And he’s made his way too, in the world.”

“One of the best grocery houses in Correze,” the old man agreed, with pride. “And before I left Paris, five cabs of my own. But I’ve always stood by the Revolution…”

It was dinner hour at the Rendezvous des Cochers et Chauffeurs. Out in the Circle, a close-packed file of taxis lined the curb beneath the agitated hoofs of an equestrian Roi-Soleil. Overhead not a window glowed in the dark facade of 18th Century houses. Concierges’ children played marelle on the empty sidewalk and an occasional autobus, tracing a noisy semi-circle across the asphalt, furnished the last reminder of the day’s traffic.

Within the restaurant, a narrow L-shaped room wedged between the walls of two wholesale houses, not a seat at the three long tables remained empty. Fifty chauffeurs, a constant number, though from time to time individual customers, with a parting “Bon Soir, tout le monde,” pushed through the crowded chairs towards the doorway, their departure followed by the cough of a starting motor and the rack and grind of gears. Fifty chauffeurs in compact noisy rows between the zinc bar, its red and green aperitifs, its heaped froduits d’ Auvergne — sausages, hams, and goat cheese — and the tiny kitchen where Big Marcel’s wife and his two plump sisters — the restaurant is a family affair — moved in a haze of savory smoke.

At the far end of the room, Big Marcel the proprietor — until six months ago he was a chauffeur like the rest — bent above the table where a stout old man with bristling white mustache in a round red face spoke earnestly to an interested group.

“I learned my lesson back in the eighties,” he told his hearers. “You young fellows never drove a horse, but it’s all the same. Cochers yesterday and chauffeurs to-day, there’s not much we don’t know about the rottenness of the class on top.”

“You’re right we do,” agreed one of the younger men. “By the time you’ve toted drunks, driven senators to bawdy-houses, and other respectable citizens to parties in the Bois…Pah!” he spat noisily over the table rim.

“And the women,” remarked his neighbor. “Just now I’m driving a dame from one of those grand apartments up on the Avenue d’Jena. She’s afraid her own chauffeur might tell her husband. Every night at a quarter past ten…”

“Rotten crew,” nodded a third. “Only it pays.” He grinned cynically across the steaming plate of soup.

“Oh, yes; it pays! That’s a fine bourgeois’ point of view! An extra ten balles for slipping a drunk past his concierge, or lending a…hand in a partouze at the Bois — and the devil take the rest!”

“Look here, I’m no professional night-hawk. Only I don’t see why all the profits should line the pockets of a lot of Russians–”

“Careful, you talk like a chauffeur francais.”

“The hell I do! I’m every bit as good a unitaire as you. But I’m not going to let a crowd of princes and White colonels spoil the profession.”

“Mais oui, mas oui,” the old man at the head of the table broke in impatiently. “There are jaunes in every trade; And we all have to earn a living. Only stand by the union, boys, and don’t lose sight of the Revolution. That’s the essential. Look at me; for forty years…” The “uncle” was off again. This time no one interrupted, for Big Marcel’s wife had just set down a steaming plate of cassoulet in the middle of the table.

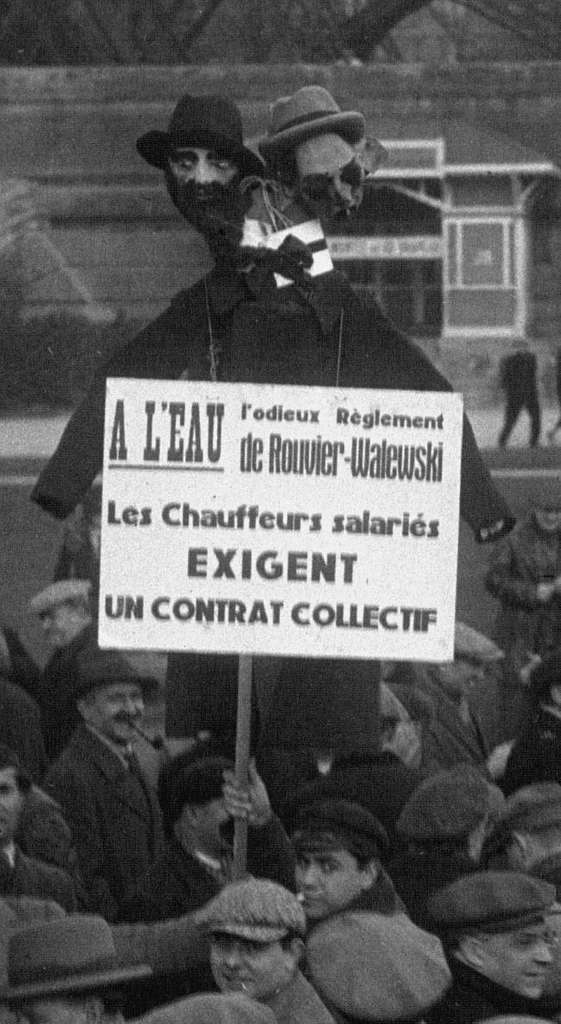

One of the most interesting groups of French transport workers is formed by the “red” taxi-drivers of Paris. They represent sixty per cent of the fourteen thousand Paris chauffeurs-sixty percent who are members of the red union, the Syndicat Unitaire y C.G.T.U. Of the non-union taxi-drivers, many are “white” Russians, debris of the Wrangel army, recruited by the big taxi companies to offset the influence of the 8,500 revolutionaries. A year ago an attempt was made — at the instigation of the same taxi companies — to create a “patriotic” organization, les chauffeurs francais, which was to group the exclusively French elements among the non-union chauffeurs. The attempt proved unsuccessful; within a few weeks every tri-colored badge of the new organization had disappeared as if by magic from the Paris streets.

The red taxi-drivers form one of the best organized and disciplined unions of the C.G.T.U. Often they play an important role in mass-meetings and political demonstrations. Many a clash with the police has been avoided because at the strategic moment, the union chauffeurs interposed a barricade of taxis between the crowd and the charging agents. At the recent funeral of a red driver killed in a collision with a “bourgeois” auto, several thousand taxis took part in the funeral procession, tying up traffic for several hours in one of the busiest quarters of Paris. During the last elections, every night dozens of taxis carried Communist speakers to all districts of the departments of Seine and Seine et Oise. The Communist Party paid for the gas, but the drivers offered their services — from seven o’clock until often two or three in the morning — after their day’s work.

For the average Paris chauffeur the eight-hour day does not exist. Generally he spends from ten to fourteen hours in the streets. He pays for his gas at the union rate, ten francs for five litres. The taxi companies generally allow him a rebate of three francs on every five litres after the first ten. His percentage of the receipts varies progressively from 27 to 42 per cent. His day’s earnings vary between fifty and a hundred francs. Certain of the smaller companies pay their night drivers a fixed rate, from 35 to 45 francs. A few chauffeurs own their taxis; there is also a co-operative — the Syndicate Taxis — with several hundred cabs.

Nearly all taxi-drivers come from the country. They are peasant boys from the mountain regions of the center — Correze, Creuse, Aveyron, and Lot — a tradition that dates from the days of the horse cabs. These “immigrants” form a transient population who live during their stay in the capital in the suburb of Levallois, a veritable city of chauffeurs. Few of them settle definitively in Paris. Like the postmen from Ariege, the policemen from Corsica, and the coal-and-wine merchants from Auvergne, their ambition is always to return to the fays after ten or fifteen years on the “box.” In the old days, the excab driver generally passed from the transports into the alimentation and put his savings into a country store. But the chauffeur on his return to the village is more inclined to set up shop as a mechanic and spends his days tinkering with farm machinery, bicycles, occasional autos, and more recently, radio apparatus.

To the village and its outlying farms, he represents the city, and what is more important still from a revolutionary point of view, the organized workers of the city. He becomes the hyphen, the connecting link, between the peasant and the factory. He reads l’Humanite and his shop is a center for the discussion of radical politics. Generally he is a mortal enemy of the cure. In many an instance he and he alone furnishes the initiative for organizing agricultural workers and tenants, or creating a local “cell” of the Communist party.

The red chauffeurs of Paris are propagandists of the. Revolution throughout the region of central France.

“Tiens, voila Paul! Bon jour! Bon jour!”

A familiar figure, the editor of the communist daily, pushed his way between the crowded tables. The chauffeurs greeted him with noisy affection.

“Sit down with us, vieux! And what’ll you have?”

“Sorry comrades. No time for dinner. Just a bouillon, Marcel. I’ve got a meeting at Ivry.”

“Ivry? Then comrade, take your time.” A big chauffeur leaned across the table towards the newcomer. “Got to go to Ivry myself. I’ll take you along.”

“On your way home?”

“That’s my affair.”

“But your evening?— your work?”

“Dis done, tu veux m’infurier? There’s work— and work. To-night I’m going to work— for the propaganda!”

NEWS ITEM PARIS, May 1, 1927 — Communist labor leaders today presented the French capital with a delightful vision of what Paris was like thirty years ago, for the leaders called out every taxicab driver in Paris and not a single hired car was on the streets. The strike of taxicab drivers was the only manifestation of this May Day, a day usually fraught with revolutionary menace.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1927/v03n02-jun-1927-New-Masses.pdf