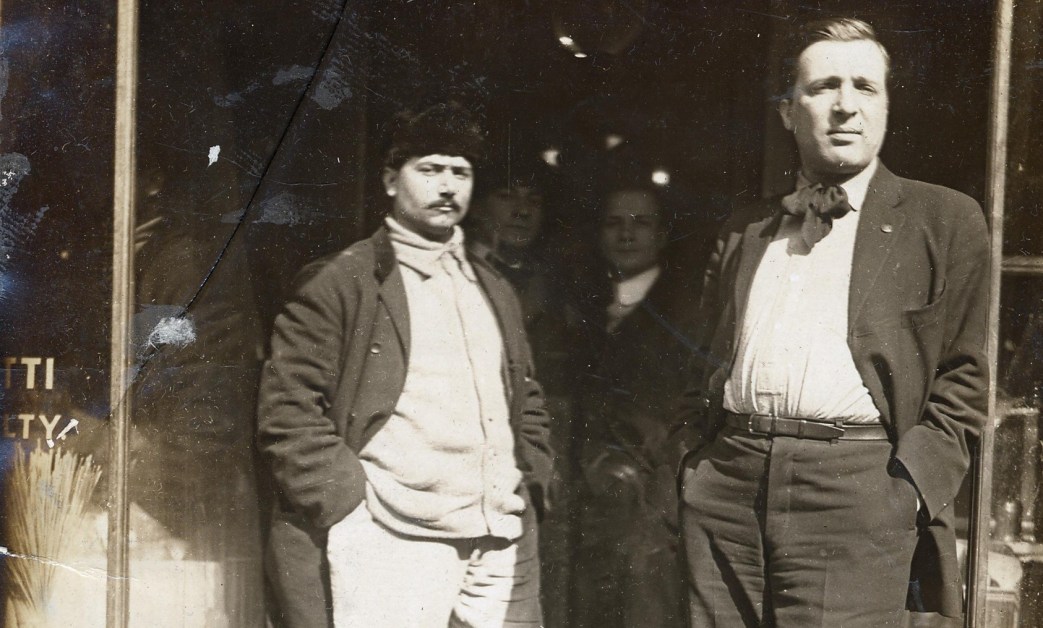

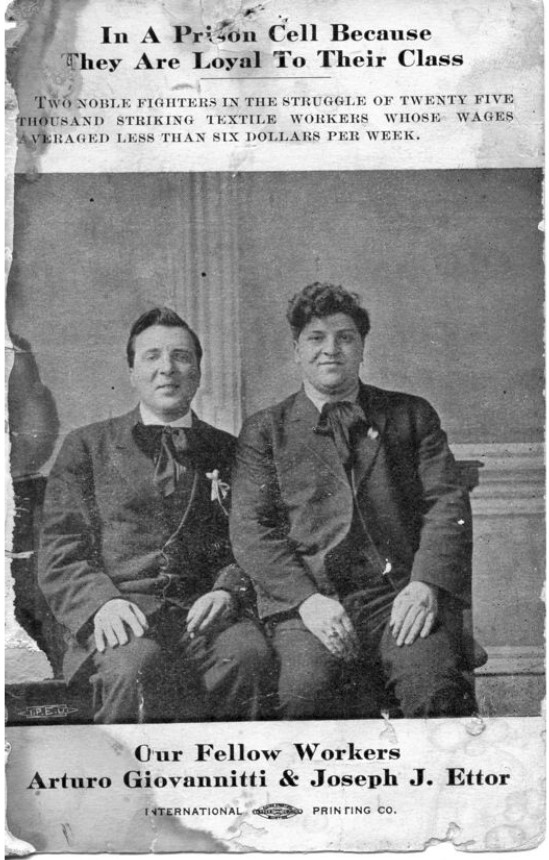

The poems of Arturo Giovannitti were a staple of the pre-war Left and graced many of the era’s finest journals. His activism in 1912’s Lawrence Strike led him to be charged with murder along with Joseph Ettor, for which he potentially faced death. His poems written in jail brought him to national prominence for the first time. Because of his leading activism, Ettor was at the time far better known and here Justus Ebert attempts to remedy that with this introduction to Giovannitti’s life. It was said Giovannitti’s eloquent address to the jury aided in the two’s acquittal in November of 1912.

‘Arturo Giovannitti’ by Justus Ebert from Solidarity. Vol. 3 No. 23. June 1, 1912.

Interlocked in the great Lawrence strike with the name of Joseph J. Ettor is that Arturo Giovannitti. Throughout the land we hear references to the “Ettor-Giovannitti trials.” Ettor was the chief leader at the memorable and victorious textile struggle; Giovannitti, the orator. To him fell the task of arousing enthusiasm, aiding and cementing the ranks and driving home the lessons and tactics of the hour among the Italians who were A prominent factor in the strike. And well adapted was Giovannitti for the task. Tall, robust, with a powerful voice, intense, earnest, incisive of speech, and a leonine manner, he made a forceful, rousing impression on his hearers. Nor was the knowledge derived from working class experience lacking; for Giovannitti’s career in America has been typical of the proletarian struggle for existence under advanced capitalism, such as prevails here.

Giovannitti was a miner, bookkeeper and teacher before he became the editor of Il Proletario, and the Italian orator of the Lawrence strike. In the bowels of the earth, he wielded a pick in the coal mines of Canada; and he has slept and starved as an unemployed worker in winter, on the benches of the parks of this city of New York. Giovannitti has traveled far, physically and mentally, only to learn those facts about capitalism that bring conviction and eloquence to the men in the movement destined to bring about its overthrow–the movement towards socialism, towards industrial democracy, and for the workers as against the shirkers.

Arturo Giovannitti is an American by experience, but an Italian by birth. Compobasso, a city of 40,000 inhabitants in the province of Abruzzi, Italy, is now better known for his having been born there. Giovannitti has put it on the map. He is now 28 years of age. His family are liberals and socially well connected in the city of his birth. His father and elder brother are physicians; his younger brother a lawyer.

Together with his mother, they are very much interested in his case. His father desired to come to this country to aid in his son’s defense, but filial regard caused Giovannitti to dissuade him from doing so, as he wished to spare his aged parent the travail and pain attending such an event. Giovannitti was educated in the university of his native city and left there when 16 years of age to seek his fortune in this land of golden promises a brutal realities, like many of bis fellow countrymen. The reason for the emigration Giovannitti has well set forth in a recent article in the International Socialist Review, on the cause of the Italian war in Tripoli.

As an illustration of his ability as a thinker, and as a specimen of his style as a writer and orator, this article is typical. It may also be quoted because of the light it sheds on the immigration problem. Says Giovannitti: “The Italian proletariat, especially in the south, has remained through the last 40 years what it has always been, the same people of old, mostly addicted to agriculture, stock raising and other labors that are strictly confined to the surface of land. Now during these 40 years the population has steadily grown with that impetus that has made Italian fecundity famous all over the world, whilst the land has remained the same.

“The Italian bourgeoisie having through their utter lack of courage and capacity, been unable to create industries adequate to the necessity and even to apply modern systems to farming that the and might have grown more productive, has been left to face a desperate problem–that of maintaining 35,000,000 people on the resources of the country and at the same time keep their own profits at the same level. After years of discussion, scheming and heavy thinking, they have been able to find only one solution: to depopulate the country.

“The only remedy, then, that was left Was emigration. For the last 30 years the Italians have been emigrating at the rate of three to four hundred thousand a year, flocking mostly to the United States and South America. Here, however, the Italian peasant, which gives the highest percentage of emigration, has lost its characteristics, and having developed at home a sullen hatred for the land which has been such a cruel step-mother to him he has refrained from agriculture and invaded the industrial fields.

“Had the Italian peasantry in the United States taken to farming, they could, perhaps, upon their return home do what the landlord bourgeoisie had not been able to do; develop, fertilize and till the soil after the scientific American ways and still manage to live–but they have become industrialized and as the few Italian industries are over-crowded, it follows that all those who emigrate to the United States are entirely lost to the mother country. The few that return home either become small proprietors and business there, or, and this in most cases, sell whatever they have however they best can, gather all their family and clan and sail again for America.”

It was this profound sociological tendency that caused Giovannitti to drift to America 12 years ago. After knocking about at various jobs, he obtained employment in a coal mine in Canada nine years ago. It was in the dominion that he got his first taste of modern industrialism on an advanced scale. Giovannitti, two years afterwards, secured a clerical position in Springfield, Mass. There he became a socialist. He was also very much interested in the protestant religion and preparing to enter the ministry, he took the degree of Bachelor of Arts in a seminary. It is a striking testimonia! of the man’s personality that though he has drifted away from protestantism, his former teachers are at present standing by him and are very much interested in the legal proceedings intended to deprive him of his life.

Shortly after, Giovannitti came to New York. Here be joined the Italian Socialist Federation. He was a member of the La Lotta Club (The “Struggle” Club). During the discussion between La Lotta Club and Circolo Socilista di Bassa Citta (Downtown Socialist Club), Giovannitti became a convert to syndicalism and revolutionary action. While a member in La Lotta, he was engaged by the uptown branch of the Y.M.C.A., West 58th St., to deliver a religious talk. This led to a misunderstanding. He was regarded with distrust, though he was at this time without a home, without employment and was compelled to sleep in the parks in winter. Giovannitti did not live by selling his ideas. He is a man of conviction and willing to suffer for them. This incident in his own life was the cause of a poem by him entitled “The Blind Man,” which has been very much admired.

It was at this time that Giovannitti became a bookkeeper in this city. Such was bis interest in all matters of progress and science that his room on West 28th St. became the nightly meeting place of men of various nationalities interested in literary, artistic, political, economic and other questions. These nightly discussions broadened the intellectual horizon of Giovannitti.

Like many another I.W.W. speaker and organizer, Giovannitti is a polyglot. The I.W.W. is a polyglot organization, that is, an organization in which all languages are represented. Giovannitti speaks English, Italian, French and Latin fluently, and has taught them all, the latter especially.

Three years ago Giovannitti became the editor of II Proletario. He made it an organ of industrial unionism, and under his direction, it became a power among the Italian working class, and a means of bringing him into greater demand as speaker and agitator. Among the Italians Giovannitti is regarded as a proletarian thinker, writer, poet and orator of no mean ability. The capitalists of Lawrence, Mass. are determined to confirm this opinion most emphatically, if the working class of this country will permit them to do so without a vigorous protest that will bring their fiendish scheme to disaster.

Giovannitti is not only highly regarded among the Italians in this country, but also in Italy. The May number of the Almanacco de L’Internationale” (The Almanac of the International), published at Parma, Italy, contains one of his poems Italian entitled “Il Boccale.” The poem is prefaced by a note commendatory of Giovannitti’s poetical powers and his devotion to the working class, especially at Lawrence.

The following Whitmanesque lines are at once suggestive of Giovannitti’s undaunted spirit in the present crisis, and his reciprocated devotion to his companions in the class war on the textile kings of New England:

THE PRISONERS’ BENCH.

In the court room at Lawrence, Mass. TO JOSEPH J. ETTOR, by Arturo Giovannitti.

Passed here, all wrecks of the tempestuous

mains

Of life have washed away the tides of

time;

Rags of bodies and souls, furies and pains,

Horrors and passions awful, yet sublime.

All passed here to their doom. Nothing

remains

Of all the tasteless dregs of sin and crime

But stains of tears, and stains of blood and

stains

Of the inn’s vomit and the brothel’s

grime.

And now we, too, must sit here, Joe.

Don’t dust

These boards on which our wretched

brothers fell;

They’re still clean-there’s no reason for

disgust;

For the fat millionaire’s revolting stench

If not here, nor the preacher’s saintly

smell–

And the judge,–he never sat upon this bench.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1912/v03n23-w127-jun-01-1912-Solidarity-SD.pdf