Martha Graham’s influence on the aesthetic and self-conception of the U.S. left during the 1920s and 30s was enormous; an impact far beyond the world of radical dance. Critic Edna Ocko gives a contemporary look at why that was so, and why Graham was also a source of frustration for the left.

‘Martha Graham Dances in Two Worlds’ by Edna Ocko from New Theatre. Vol. 2 No. 7. July, 1935.

IN times like these, when revolutionary art is the banner for a class marching into power, the artist must work against time. He must wrest from incipient Fascist censors whatever he realizes is valuable for the perpetuation of his art, and his works must be rich in content since he speaks for and to a rising social class, and realizes that he must be the crystallizer and organizer of their feelings. This places an enormous responsibility upon him, particularly when the field in which he works is limited, since he must constantly guard and proclaim the interests of the class he champions.

In the modern dance, the task is less simple than one at first believes. There are so few great dancers in the world today that the temptation to make a mechanical and arbitrary division between revolutionary and bourgeois dancer is difficult to avoid. And it is to skirt this danger that one considers Martha Graham not only as the high point of the bourgeois dance, but also as an artist whose work, while still encircled, is drawing closer and closer to the belief in and expression of a new social order.

At the close of the dance season of 1935, Martha Graham stands almost unquestionably as the greatest dancer America has produced since Isadora Duncan, and as one of the outstanding exponents of the modern dance in the world. We must determine then, the philosophy by which she creates and through which she interprets social phenomena, since, in her position as leader, she is a determining influence upon a vast number of ‘disciples.’

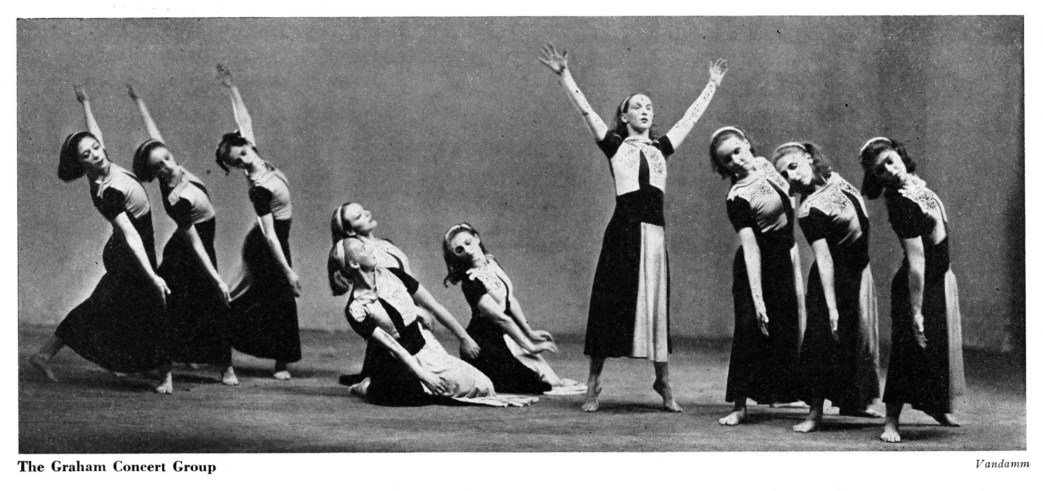

As a performer, her sincerity and integrity is unquestioned. She has never consciously catered to Philistine art-lovers, nor casually succumbed to the blandishments of a financially tantalizing Broadway. As a technician, she has, Picasso-like, shifted styles. This year, however, her efforts have crystallized. Hers is the closest approach to a system of dance technic which is basic, transferable, and capable of infinite variation. She has developed a science of modern dance movement which seems remarkably suited to make the body a fit instrument for expression. And this rigorous training presents itself to me, at least, as an admirable technic for the revolutionary dance. It has, above all, strength and endurance; it permits of amazing gradations in dynamics; it embodies dramatic elements of militance and courage. Its most delicate moments are fraught with latent power. When the body stands, it seems immovable. The body in motion is belligerent and defiant. It seems almost impossible to do meaningless dances with this equipment. In training, the pupil is told to be strong, “strong enough to destroy barriers,” that her body must surmount all physical difficulties, must be “energy on the move,” creating and recreating strength and change within itself. This technic has produced dancers definitely aligned to the militant working-class movement whose merits as directors, teachers, and soloists, cannot be gainsaid. Anna Sokolow, and her Dance Unit in Anti-War Cycle, and Strange American Funeral, Lily Mehlman, Sophie Maslow, all show to advantage. the results of this training. The Graham Concert Group has reached a high technical standard, and its presence on a stage literally surcharges the air with energy and militance. There is no question that Martha Graham has succeeded in founding a school of the dance that is a major influence throughout America.

It would be absurd at this time to assume that Miss Graham, as a creator, is concerned with the expression of personal vagaries, that her thinking is hap hazard, willful, uncharted. Tracing the course of Miss Graham’s dances would be charting an Odyssiad. At times she drew close to a welcoming realistic shore, then the tenuous siren songs of mysticism, abstraction, purism, drew her out of her path into strange, unfrequented waters. We assume that this pilgrimage is ended, that she has dropped anchor in the rich harbor of social realism. What are her dances, then, of social content?

IN 1929, the year of the stock crash, of the collapse of bourgeois security, the following dances comprised, among others, Miss Graham’s program: Vision of the Apocalypse, in which a figure views the suffering and miseries of an enslaved humanity; Sketches of the People, which, according to a reviewer at that time, proclaimed “social revolution”; Immigrant, composed of Steerage and Strike; Heretic; Poems of 1917 in two parts; Song behind the Lines; Dance of Death, the latter anti-war dances. These were presented at a time when most performers were doing isolated sketches on a variety of unrelated, superficial topics.

There was, in the years following, a definite tangent shot away from this realistic direction. The works of Martha Graham became mystic, Mexican, Hellenic, Medieval (Ave, Salve, Ceremonials, Tragic Patterns, Ekstasis, Dithyrambic, Bacchanale, Integrales). Then, last year, came Frenetic Rhythms and Theatre Pieces. In the third Frenetic Rhythm, and in Sarabande, from Theatre Pieces, a fissure was growing, separating these period-cycles from a new approach to contemporary material.

We find her today on a border line which she has not yet had the determination to cross. Her programs show the result of this indecision; some of the dances have social correlatives, others remain unalterably abstract. Her recent works have been the dynamic Celebration, a group dance for which the subtitle suggested by Miss Graham was “May Day”; American Provincials, composed of Act of Piety and Act of Judgment, using the New England locale for an exposé of Puritan hypocrisy; Course, a thrilling extended opus, with the group chorus interspersed with trios and duets each have its purposeful symbolism, Perspective in two parts, Frontier and Marching Song, Three Casual Developments, and Study in Four Parts.

Martha Graham, in conversation, grants specific social content to the interested interpreter of her dances. The two Figures in Red in Course, for instance, danced by Lily Mehlman and Anna Sokolow, were definitely symbols of Communism. Miss Graham sincerely believes herself a revolutionary artist, a believer in a new social order based on the strength and convictions of the working class. As a creative artist, however, she feels she must remain isolated from the roaring current of the revolutionary movement. This artificial separation leads to great differences between her subjective sympathy with the working class, and her actual presentation of that sympathy in dance form.

The dance Strike, composed in 1929, was the second of a suite called Immigrant, which entertained the erroneous intimation. that foreigners, “immigrants,” fomented strikes. Today that dance would be inimical to the best interests of militant American workers. In dances like Heretic, American Provincials, the solo figure is the rebel, the mass reactionary; the mass, unsympathetically conceived as brutal and unyielding, condemns or destroys the revolting individual. This concept, a romantic acceptance of the ignorance of the mass opposed to the prophetic Byronic “artist,” is unsound. Dances like Dance in Four Parts, Three Casual Developments, lingering on the current programs of Miss Graham, remain technical tours de force, with a minimum of rational communicability to the audience. Involved at first in the need for developing a form, she has remained too inextricably bound up with that concentration to work unhampered and clearly with material. The worker is mystified, irked by non-comprehension.

Although Perspective is an unfinished work, if it continues as an historic survey of America, it must avoid the dangerous shoals of nationalism. John Strachey in his discussion of Archibald Macleish, written before the appearance of Panic, says: “…I would be the last man to object to the expression in poetry or anywhere else of a man’s natural love of his own country. We must, and should, all of us, have deep roots in that particular part of the earth upon which we were born…Love of country, however, is not incompatible with love of the future instead of love of the past.” This concern with the past is clearly apparent in American Provincials and Perspective.

MISS GRAHAM still makes her affirmation of the future in such abstract terms that the average audience must create, out of good faith in the artist, the ideational background for this future. If she will make of her dance, as she describes it, “a social document,” Martha Graham must decide for whom, for which society she speaks. Is it for a nation? Is it for a class of people? If so, when will she reach out to that class of people and dance for them? Whatever confusions exist in the work of Martha Graham, this much is true: her technic has elements which make it ideal for depiction of militant evaluations of society, her dances more and more approach realistic social documentation, and her verbal sympathies are avowedly one with the revolutionary dance. Will she openly assume leadership in the vanguard of revolutionary art, or will she be the last stronghold of a departing social order, and let her disciples champion new causes? This she must decide for herself.

There are millions of workers over the country who will support her, as they have supported all artists allied with them. But she must clarify not only her stand, but her approach; only by dancing for this audience can she learn which of her creations speak for them. That process in itself is probably the greatest educative and critical process any artist can undergo. Perhaps the coming year will bring Martha Graham to her potential audience. One cannot dance forever in two worlds!

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v2n07-jul-1935-New-Theatre.pdf