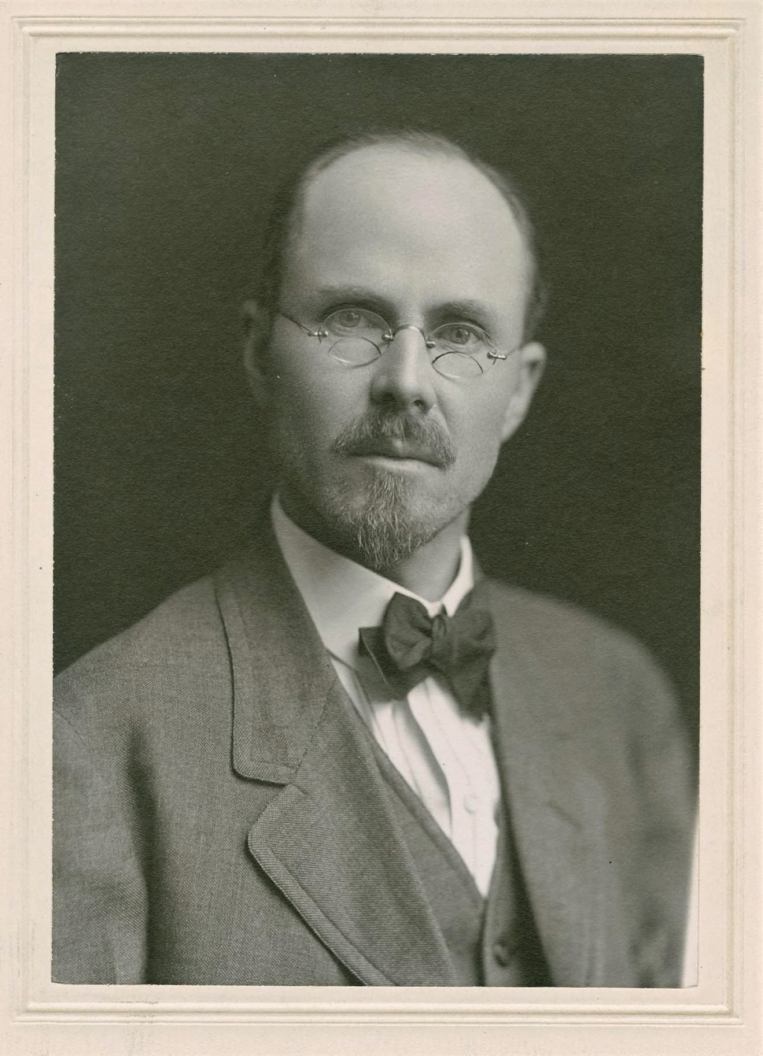

I can not vouch for Charles H. Kerr’s history, but I can for his sincerity in this pleasure of an essay on a subject clearly a passion for the ISR editor; what the society built by ‘freemen of Ancient Athens’ was and what it might mean for Socialists of his day.

‘The Freemen of Ancient Athens’ by Charles H. Kerr from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 5 No. 1. July 1904.

THE materialistic interpretation of history, first discovered and formulated by Marx and Engels and first adequately elaborated by Labriola, is only now beginning to be applied, at least in writings accessible in the English language. The histories to which we must go for our facts if we would know anything of the past life of the world are still the histories written by men with theological or other ideological explanations for the course of events, by men who believed that ideas fell from heaven or were bestowed upon the race by gifted individuals who arose from time to time, and each in his turn infused new life into a sluggish, stupid humanity.

Yet these old historians and the sheltered, conservative scholars who cling to old traditions have preserved countless facts of untold value, which only need to be re-interpreted in the light of historical materialism, to make the past history of mankind luminous with meaning and prophetic with the promise of a larger life for the generation next to come.

My subject in this article is the freemen of ancient Athens. I wish to speak in particular of that period of Athenian history, the fourth and fifth centuries before the Christian era, and more especially the last half of the fifth century, in which were produced so large a proportion of the works of literature and art which have left their impress on the intellectual life of the world ever since. Was it by accident that in this one, city at this one epoch the mind of man reached heights that have scarcely been equaled through all the ages, even amid the material achievements of the last hundred years? If no accident what was the cause? This is a riddle that has baffled the historians of all subsequent ages, and only the socialist has the clue to the answer. It is found in our fundamental principle of historical materialism.

For an adequate statement of this theory, it is necessary to go to Marx, Engels or Labriola, but this time, instead of quoting from these writers, I will try to give a brief summary of the theory in easier and simpler language than they employ. I am well aware that I shall be sacrificing complete accuracy to simplicity, and I trust it will be understood that I am not attempting a scientific definition.

Human beings, in order to live, are obliged to provide themselves with food, and, outside the tropics at least, with clothing and shelter. All human beings of whom we have any definite knowledge have supplied these material wants by some sort of associated labor, from the communal gens of the Iroquois Indian to the capitalist society of today with its wage slaves and its trust magnates. Now the discovery of Marx is that each successive industrial system, by which the people of any given time and place supply their material wants, is the determining cause of the political systems which accompany it or follow it, and likewise of the general currents of thought, opinion and feeling which accompany or follow it. In other words, it is not the ideas of men which determine their material conditions, but, speaking generally, it is, in the last analysis, the past and present economic conditions which determine the prevalent ideas, and in fact the whole current of what we call intellectual life. This does not mean that ideas have had no part, in the progress of the human race, but it does mean that every victorious idea has had its roots in a definite economic situation, and could not have developed had the economic situation been radically different.

There is a sharp contrast between the social life of the self-governing cities of Greece, and that of the despotic monarchies of vast extent which covered western Asia and northwestern Africa. One obvious cause for this difference lies in the geographical character of the territory. The level plains of Assyria and Egypt were favorable to the movement of large armies, and the primitive communism of these countries was crushed out by the growing military power of rising rulers, at least two thousand years before the Christian era.

Greece, on the other hand, is cut up into little valleys by steep mountains, while a large part of its territory is composed of islands large and small. The communal system thus persisted far later than in Asia, and its traces are distinctly visible in the organization of the state of Athens as we find it at the earliest historical period. And as clans and tribes evolved into states, with ruling and subject classes, each valley and each island in Greece became a state by it-self. Frequent wars between tribes and the discovery that a prisoner was a valuable asset, since he could produce more food than he could eat, had made general a system of chattel slavery throughout the states of Greece. The slaves were not members of an inferior or alien race. They were almost always native Greeks, of the same blood as their masters, and with the shifting fortunes of war, it was not impossible for master and slave to change places. Agriculture was of course the main industry, especially in the earliest historical period. But Greece was not only mountainous, it was also easily accessible to the sea, with a multitude of good harbors, and the timber for ship-building ready at hand, and so it was that the Greeks became a sea-faring people, exchanging their own products with those of Phoenicia, Egypt, Italy and the other shores of the Mediterranean. Piracy in those days was a respectable industry, and necessarily every merchant ship had to be a war ship in self-defence.

Thus about the year five hundred before the Christian era we find the people of Greece living in their little self-governing states, gaining their living by agriculture and commerce, using slave labor to a limited extent, and mainly taken up with their wars between city and city, and with their spreading commerce. They had founded colonies wherever their ships sailed, and some of the most important of these colonies were cities on the west coast of Asia Minor. At the time we are considering the king of Persia had consolidated under his rule all the other great monarchies of western Asia, and laid siege to these Greek cities. They called on Athens, the largest city in Greece, for help, and the Athenians accordingly fitted out an expedition. It did not save the Greek cities of Asia from capture, but inflicted considerable damage on the Persians, and drew down the wrath of the Great King upon Athens. He fitted out a fleet to attack the city of Athens. It was wrecked in a storm and the expedition came to nothing. The king persevered, and in the year 490 B.C. fitted out the famous expedition we have all read of in our school books, which landed near Marathon, on the coast of Attica, near Athens. The battle of Marathon resulted in the defeat of the large Persian army by a much smaller army of Greeks. It is what the old-fashioned historians call one of the world’s decisive battles. Perhaps it was, if battles ever are decisive. But there were economic forces that turned the scale in the battle of Marathon, and it resulted in its turn in a re-adjustment of economic forces that were to bring about immense changes before a generation passed away. The Persian army was composed largely of unwilling soldiers drawn from subject nations, forced on pain of death to go to an unknown country and fight the battles of the Great King. The Greeks were the rulers of their own state. They had no theories of natural right and no conscientious principles whatever against the system of chattel slavery, but when it came to applying that system, they preferred to be on top rather than underneath, They won the battle of Marathon, and the moral effect of that battle was to give confidence to the Greeks in subsequent wars with the Persians, and to increase the prestige of the city of Athens among the other Greeks. The Athenians, or at least the wiser heads among them, knew that the Persians would not be satisfied with the result of the battle. The Persian king died soon after, and Greece thus gained a breathing spell, which the Athenians used in building more ships. Ten years after the battle of Marathon came the famous invasion of Greece by the immense army and navy of Persia under Xerxes. Conventional historians waste most of their enthusiasm in describing this war, over the battle of Thermopylae, where three hundred Spartans threw away their lives in defending a pass after the enemy had already found another way around. This historical episode reminds me of the remark of the little girl who had been regaled with Mrs. Hemans’ story of Casabianca,

“The boy stood on the burning deck Whence all but him had fled,”

and staid there until burned up because he had been ordered by his father to remain until further notice, and an untimely death on the part of the father had prevented the further notice. The opinion of the little American girl was, “I fink he was dreffle good, but he wasn’t the least bit smart.” So with the Spartans, they may have been dreffle — but they didn’t display any great amount of brain work.

The Athenians were different. When the Persian army, said to number a million men, reached the neighborhood of Athens, they didn’t stand their ground and fight against overwhelming odds until the last Athenian was slain. That might have made fine material for poets, but the Athenians were strictly materialistic. They moved their wives, their children and their movable property from the mainland to a neighboring island, while their fighting men went on board their ships and with rather ungracious support from the other Greeks, met the Persians where they were weakest, at sea. Persia was an inland country, and its fleet was drawn from subject nations who were none too enthusiastic in fighting for their conquerors, moreover, they were no match for the Greeks in naval tactics. The Persian fleet was driven from the coast of Greece, then pursued home and demolished there. The land campaign dragged on for a year, but the Persians finally withdrew in defeat, never to return. It was at sea that the real contest was fought out, and the smaller states of Greece were obliged to recognize that it was to the energy and vigor of Athens that they owed their escape from slavery to the Persians.

The Athenians, as I have said, were materialistic, and they were not slow in utilizing this sentiment for practical ends. They organized at once a confederacy of the maritime states of Greece, under their own leadership. The object of this confederacy was to keep the Aegean sea clear of Persian warships. At first each city provided its quota of ships, but by insensible changes one city after another began to pay a sum of money instead of furnishing war vessels, until finally the confederacy had become an empire. Athens provided the ships and the marines while the subject cities put up the money.

As every socialist knows, the character of a people is modified profoundly by changes in its way of getting a livelihood. Let us then try to get a glimpse of the economic change that came about in Athens as the maritime supremacy of this city became an established fact.

The new revenue, which made Athens the wealthiest city of Greece, arose partly from the direct money tribute of the subject cities and partly from the commerce with countries near and far, now made possible by the fact that the Athenian navy commanded the seas, and could protect its merchants and merchant ships wherever they went, an advantage far more rare and important in those troublous times than it seems now.

Private wealth in Athens increased by leaps and bounds. But there was a distinct obstacle to its concentration in the hands of a very few. The political power was not, as in more civilized nations, in the hands of a small group of plutocrats, it was in the entire body of free citizens. There were occasional attempts on the part of the better classes, as they called themselves even at that early day, to get control, but they were usually ineffective. On two occasions the aristocrats were temporarily successful, but only to be hurled from power again.

In the long run, it is the essential class which holds the political power, and in imperial Athens the essential class was the citizen soldiery, ready on occasion to put down revolts of subject cities, and to meet the enemies of Athens in the field or at sea.

So it was that the democracy remained in power. And it used its power to put pretty heavy taxes on the holders of exceptionally large fortunes, and to provide a modest support, in the way of pay for jury service and other political duties, for all free Athenians who did not draw a comfortable income from the labor of slaves. Commerce was to a large extent in the hands of aliens and freed slaves, of whom there were at the age we are considering, according to the figures of Engels, 45,000. Of free Athenian citizens there were 90,000, and of slaves 365,000.

I am not attempting to discuss the physical, moral and social status of these slaves who made up the greater portion of the population, nor shall I try to discuss the question of whether slavery was right or wrong. The Athenians were fond of ethical discussions, but we have no record of their discussing this question. Slaves then were the same necessary element in production that machinery is today. And by the way, at Athens the slaves were private property, while at Sparta they were collective property, but that slaves could be dispensed with simply did not occur to either Spartans or Athenians.

Some facts are preserved regarding the social status of the slaves, but they would be irrelevant here. We are now concerned with the freemen.

Here at Athens was a situation absolutely unique in the history cf the world even up to the present day, yet presenting a striking analogy with the probable situation when collectivism shall have been established. Here were ninety thousand men, women and children in a single community, all raised above the need of drudgery and the fear of want, with a large degree of freedom and an abundance of leisure. If we were to accept the theories of the opponents of socialism, we should expect to find a brutish degeneracy, a reversion to savagery. What as a matter of fact we do find in this one epoch and in this one city, is the most intense intellectual life that the world has ever known, a life that produced the tragedies of Aeschylus. Sophocles and Euripides, the orations of Pericles and Demosthenes, the dialogues of Plato, and the sculptures of Phidias and Praxiteles.

To socialists there is nothing strange in this. We understand that human beings can not survive on this earth without gratifying their material desires. We understand that as long as social adjustments make it hard for each individual to gratify his material desires, so long he must be mainly concerned with them, since otherwise he probably would not survive. And we can see, too, that if a large body of people in one community, where they can act and react upon each other, could be relieved from the everlasting pressure of material wants, the way would be open for intellectual wants to rise into consciousness and dominate the life of the community. This is precisely what happened at Athens, and it does not seem unreasonable to look for like results when like conditions shall repeat themselves on a larger scale.

There is, however, one point of contrast to be noted between the motives operating on the freemen of ancient Athens and those operating on the freemen of the future collectivist society. At Athens the matter of greatest concern was to maintain the supremacy of the city by war and diplomacy, and therefore these arts were most highly esteemed and were perhaps the readiest path to distinction. In the future society the most essential thing will be the improvement of means of production, the perfecting of processes so as to produce the greatest results with the least outlay. The inventor and the efficient superintendent will thus be honored as the greatest public benefactors.

But while noting this one contrast, we must note many points of agreement. And first, ethics. The moral ideal which was current among the Athenians was not an ideal of personal holiness, of self-renunciation and saintly purity, to be rewarded by eternal felicity in some hypothetical hereafter. True, they had their traditions and their speculations about the hereafter, but we may safely infer from one of the popular comedies of Aristophanes that they did not take them very seriously. Their moral ideal was the ideal of a citizen highly developed in all his faculties and highly useful to his native city, and this ideal being a reasonable one and to an extent attainable, was sincerely held. The Athenians did not need to be hypocrites and they were not hypocrites. Hypocrisy is the consequence of a different economic situation from the one that prevailed at Athens. Most well-to-do Americans are hypocrites, but it is foolish to blame them for it, they have to be if they are to become or remain well-to-do Americans under present economic conditions. I shall not go into particulars, I do not wish to say unkind things regarding a class among whom I have friends. Besides, there is a better example to contrast with the Athenians, and that is afforded by a contemporary and neighboring nation with whom they came into frequent contact.

The Spartans, so dear to bourgeois moralists, were consummate, contemptible hypocrites. Perhaps contemptible is too strong a word. I should rather say deplorable. They were hypocrites because they had to be hypocrites to keep their commanding position, just like countless other hypocrites since. They were the descendants of a small but warlike tribe who, shortly before the historical period began, had migrated from northern Greece into the peninsula west of Athens known as the Peloponnesus, and had established themselves as rulers over the natives. They were only a small part of the population there, they had no particular advantage in the way of superior weapons, and their position as the ruling class gave them a very comfortable living on the labor of others. But this position was a precarious one, and it rested on the belief that they, the Spartans, were invincible in battle and were marvelously brave, to the point of preferring death to surrender. Now this was a colossal humbug, the Spartans were very much like other people in their natural impulses, and on one notable occasion, when the Athenians had a Spartan army cornered on the little island of Sphacteria, it sensibly chose the alternative of surrender rather than death, much to the surprise of the rest of the Greeks, who had been successfully humbugged by the Spartans for so many years.

I said a little while ago that the Spartans held their slaves as collective property. There was a necessity for this. The very existence of the Spartans as a ruling class depended on the efficiency of their military discipline, along with the popular opinion of the other Greeks as to their bravery. If they had allowed their young men to divert their interest from military affairs into the pursuit of wealth, their supremacy–would have ended. Historically, that is the way it finally did end. They kept up the pretense of superhuman bravery and contempt of wealth so effectively that they won the allegiance of most of the other Greeks, and, with their aid, finally defeated Athens in a war which lasted a whole generation. The Spartan generals then had immense resources at their disposal, they forgot their traditional contempt for wealth and went after it eagerly, the military discipline of the nation was relaxed, and with the next war Sparta was defeated and sank into obscurity, never to rise again.

The difference between Sparta and Athens was this: the supremacy of Athens rested on a genuine efficiency, intellectual as well as physical, on the part of a large body of equal citizens. There was no subject class at Athens except the slaves, who didn’t count, not being soldiers, and the freedmen and resident foreigners, who were well treated and contented. There was a substantial identity of interests among the ninety thousand freemen of Athens, and therefore it was not necessary for them to be hypocrites. They had not learned to make a virtue of total abstinence from the wine that their vineyards produced, neither had they learned to make extra profits by putting poisonous chemicals into their wines. They had not learned to sentimentalize over the eternal justice of recognizing the equality of all men, Greek and Barbarian, bond and free, but on the other hand they had not invented the sweat-shop, and they inflicted summary penalties on such of their own citizens as were guilty of cruelty toward their slaves.

The traditional religion of Athens, with its roots in an economic situation far earlier than the one we are considering, was a worship of the Olympian deities such as Homer describes, and especially of Athena the tutelary goddess of Athens. This religion was a social, not a private matter. There was no special coterie of particularly good people, who were more religious than the rest and were therefore supposed to be surer than the others of a safe passage to the Elysian fields, which by the way are rather a more artistic conception than golden streets. Quite the contrary, religion was an everyday matter for the men as well as the women, but it was closely identified with patriotism. And again, patriotism was not something that had to be harped on as a sacred duty, it was to the Athenian the natural expression of his enlightened self interest, since the welfare of every Athenian citizen was closely bound up with the prosperity of the Athenian state.

My statement may be challenged by some who have read of the Eleusinian mysteries, which undoubtedly contained the germ of the introspective, personal-holiness element of Christianity. But the interesting point to note is that these mysteries did not develop into an important part of Athenian life until the liberties of the city had been lost. When the gods ceased to provide the Athenians with the material comforts of life, and with the fullest liberty for self-expression, then the need was felt for an introspective religion by way of consolation, and the versatile Athenians developed a very good religion of its kind; indeed no one knows how large a deposit it may have left in our historic Christianity.

Introspective religions have prevailed during the world’s long night of slavery. Bu with the dawn of freedom we listen back to Athens for our moral ideas. Not purposeless self-sacrifice but rational self-development, not asceticism but the moderation that prolongs and intensifies pleasure, not humility and obedience but strength, beauty and freedom, these are the ideals that will reanimate the men and women of all the world as the victorious proletariat wins for itself the same right to live that the freemen of Athens enjoyed twenty-three hundred years ago.

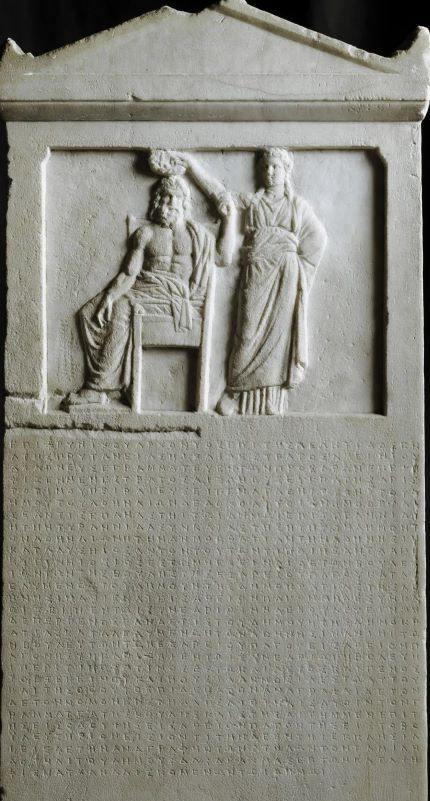

As to the art of Athens, the facts are so bewildering in their number and significance that I shall not attempt any comprehensive survey. The architectural remains of the Acropolis have served as models for Europe and America through all the ages since this era we are considering, and the sculptures are still preserved as our most precious possessions. But it is of the dramatic art of Athens that I wish to speak especially, because here 3 influence of genuine democracy upon art is most clearly manifest.

The early beginnings of the Attic drama were bound up with the primitive worship of Dionysos, the god of wine. The first festivals of Dionysos-worship of which we know anything consisted of choral singing in praise of the god or in commemoration of some of the simple legends about him. As the choruses grew longer and more elaborate, an actor was introduced, who carried on a dialogue with the leader of the chorus while the singers rested. Later, a second actor was added, and finally a third, three being the limit to the number of actors on the stage at one time even in the most highly developed Attic drama.

The festivals of Dionysos were held twice a year, and it was only on these occasions that dramas were presented. All ordinary occupations were suspended at these times, and thirty thousand men were seated in the great theater of Dionysos. It was open to the sky and the dramas were always presented in the daytime. ©n each occasion several new plays by as many different authors were offered in competition for a prize. All day long the thirty thousand Athenians listened with critical attention to plays of a character that demanded even more intellectual effort on the part of the spectator than the plays of Shakespeare. Thirty-three of these tragedies and eleven of the comedies have been preserved intact through the ages, and they are still in many respects the models of the dramatic art.

Conventional writers speak of the surpassing genius of Aeschivlus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes, the writers of these plays that have been preserved, as if the genius of these individuals explained the preeminence of Athens in the dramatic art. But we know that while these writers won many dramatic contests, they were sometimes defeated by others whose works have been lost. There was thus a large group of dramatists of surpassing intellectual power, suddenly appearing as Athens reached the economic stage we have been discussing, and disappearing when that stage was passed. Art can grow only when there is a public capable of appreciating it. And to this appreciation two things are needed, leisure and education.

Education at Athens was not thought of mainly as a means for fitting boys to earn their living. The freemen of Athens all lived fairly well, measured by their own standards, and they were not oppressed by the fear of starvation, except once after the loss of a great naval battle, when the enemy commanded the sea. What they were mainly concerned with in the training of their boys was that they should grow up into well rounded men, capable of serving their country as soldiers, orators or diplomats, but also capable of enjoying life intellectually as well as physically. Poetry and music, art and literature, were the inheritance of every freeman at Athens. This liberal education along with freedom from mere drudgery and anxiety for bread made the freemen of Athens the leaders of the world.

We hear much now of industrial education. It is perhaps a necessary swing of the pendulum back from the merely ornamental education which prevailed a generation ago. Body and mind need to be educated together. The Athenians knew that and acted upon it. Again, it is perfectly true that the progress of modern industry makes necessary extreme specialization of study and of effort, if progress is to be continued. But from ancient Athens we need to learn that no specialist can do his best work in any great undertaking without the appreciation and the criticism of a large body of people capable of apprehending in its main outlines the special work he has to do. And no specialist can do the highest work in his own chosen field unless he can take a broader view that will show him the relations of his own special work to the work of the rest.

The Athenians were not perfect. Privately I am inclined to believe that a perfect nation would be uninteresting, but I never knew of one and so can not be sure. They were emerging from barbarism just as we are emerging from commercialism. They had an inspiring sense of solidarity and loyalty to their city, just as we the workers when we turn from the final conflict for our emancipation to the task of rebuilding the world shall inevitably have a splendid sense of the solidarity of the working class, a class that by the disappearance of parasites large and small will have become as broad as humanity itself. They realized, as we shall realize, that the welfare of each was inevitably bound up in the welfare of all. They had no need to be hypocrites as we shall have no need. They accepted physical pleasures as rational if taken in moderation, with a clear view of their consequences. But they trained their children in such a way as to open up before them an intensity of intellectual enjoyment that made physical pleasures very small by comparison and made possible intellectual achievements that have stimulated the life of all who have come after.

The city of Athens was submerged by the physical force of ignorant despots, but the ideals of Athens, rooted deep in fortunate economic conditions that are soon to re-appear, not this time for a few, but for all, these ideals will re-assert themselves in the free and happy life of the world that is soon to be.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v05n01-jul-1904-ISR-gog.pdf