Rumblings in the textile industry in the late 1920s presaged the industrial union explosion of the C.I.O. the following decade. One of the most important of those were the strikes in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

‘New Bedford’s Revolt’ by Harvey O’Connor from Labor Age. Vol. 17 No. 6. June, 1928.

Textile Workers in Finish Fight

WHEN the bright sunshine of a crisp mid-April morning, i spinners and weavers, slasher tenders and doffers, streamed toward the mills. Fifty-six sombre, many-eyed mills awaited them and their daily sacrifice of toil, offered up to the thunder of flying shuttles and bobbins dancing madly.

Mothers and flappers they were, men who had fixed a thousand looms and youngsters in the packing room, joking, laughing, chattering in a half a dozen languages. Now they were people, Jenks and Archambault, Silva and Yareski; soon they would just be “hands,” changing bales of cotton into finest of cotton weaves, silk and rayon mixtures, the better cloths which vie with lordly silk for milady’s favor.

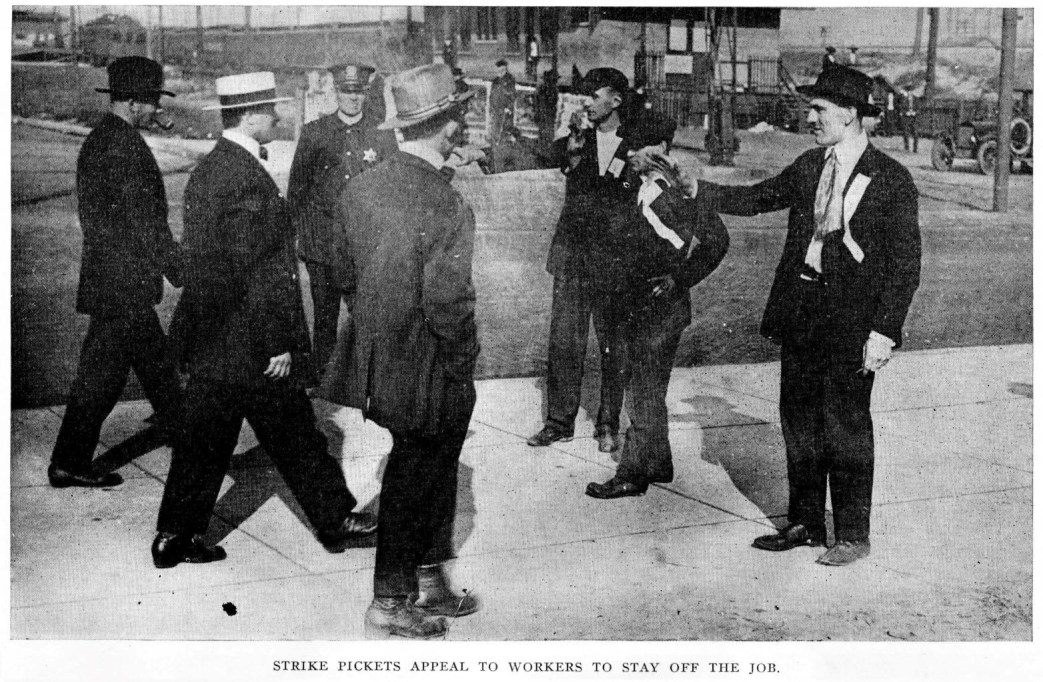

But no! Before the open mill gates they stopped. They were gathered into excited groups, talking eagerly, pointing toward the employes’ entries. But none crossed the line that separated street from mill owner’s property. Others came, were eyed attentively, then greeted. The tension that marked the first quarter hour disappeared. None had gone in. The strike was on! Once again New Bedford’s cotton mill workers had thrown defiance back at bosses intent on cutting meager wages. This time 27,000 of them stood shoulder to shoulder against the edict of the Manufacturers’ Association that an average wage of $19 a week was to be cut to $17.10.

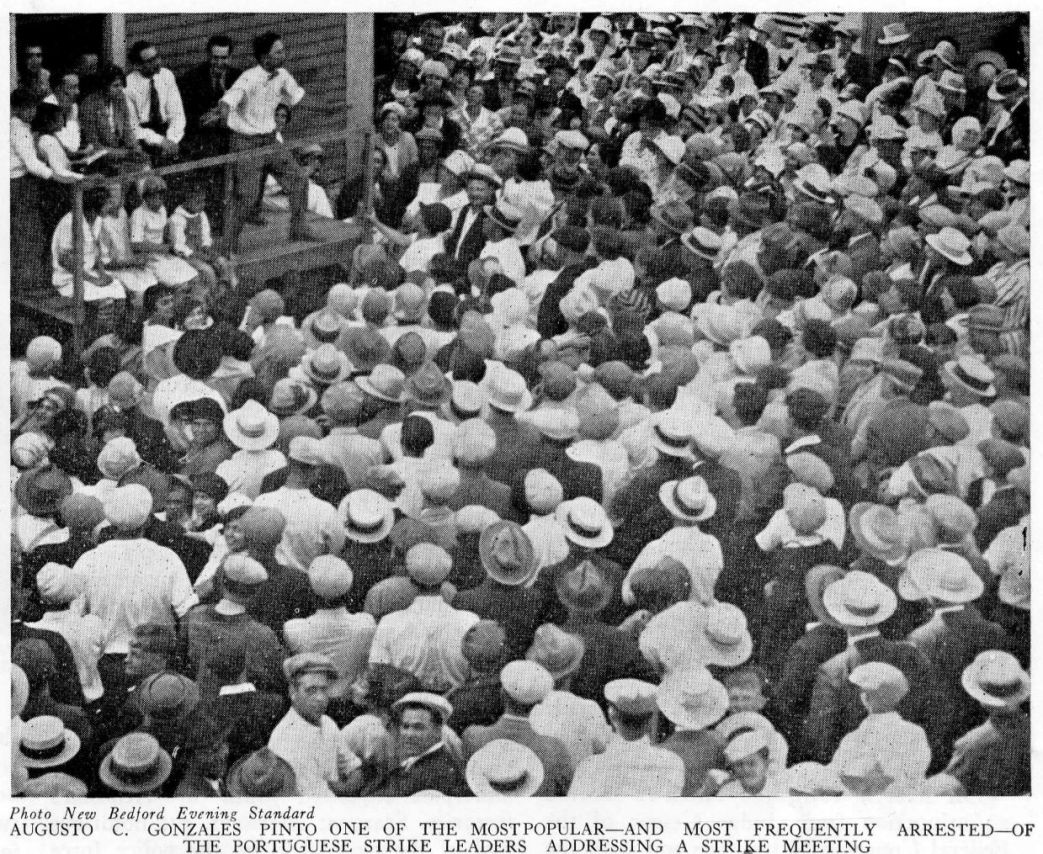

Textile council organizers drove up to group after group. From autos they shouted: “Acushnet is out 100 per cent;” “Not a man or girl in Wamsutta;” “Not a frame working at City Mill.” Cheers. Cheers for the leaders, cheers for themselves. Catcalls to the supers and the second hands huddled in the mill offices. Men danced jigs and girls clapped in unison.

By 8:30 mill gates were deserted. Strikers had returned home. Some went to bed to know the delicious feeling of sleep in morning hours. Others went fishing. Women shopped for supper. Men gathered to exchange mill gossip and bring to memory strikes of old when they had fought it out for six months—even longer— with New Bedford’s sullen, autocratic mill bosses.

They’d Sooner Starve

Weeks have passed since then; each week end marked by a laconic statement from Secretary Raeburn of the Manufacturers’ Association: “The mills will not reopen Monday;” each Monday marked by great mass meetings vowing they’ll not take the 10 per cent cut this side of starvation.

Pastors from pulpits have denounced those mill barons, led by the doughty William M. Butler, confidant of Calvin Coolidge and chairman of the Republican National Committee. Pastors have quoted the Methodist social creed, the Catholic bishops’ program, the pronouncements of the Federal Council of Churches on industrial relations. They have told the strikers that they are right; that industry owes them, in return for their labor, a decent living.

Editors have stormed, not against strikers, but against mill owners, branding them as inefficient, incompetent, short-sighted. Merchants, hit by the threat of 10 per cent less cash in their tills, have not mounted Rotary and Kiwanis rostrums to attack union men and women. New Bedford’s business and professional classes know who butters their bread.

Who are these strikers, holding aloft in a corner of the old Bay State the banner of textile unionism and showing labor in other cities how a strike can be called and made to stick? Old Lancashire men and their wives, they are, the people back of the textile unions. The Weavers’ Protective Association’s charter, dated 1891, reads of names common in Bolton, Oldham and Manchester. Unionism is four generations old in the gaunt bones of these English people. Then there are native Americans, chased from Massachusetts’ spare soil into the mills. Another wave, that of French-Canadians from old Quebec. These races and mixtures are the backbone of the seven unions which have stuck it through in New Bedford when textile unionism elsewhere was hard put to it.

Portagee and Polack

Back of them, in the more unskilled callings in the mills, are thousands of Portuguese and Polish workers —Portagee and Polack—without the traditions of unionism, in a strange land, cut off by language from their neighbors, clustering about their separate churches, their Narodni Doms and Casas portugesas.

35,000 workers there are in New Bedford’s mills; 8,000 still working in mills where the wage cut was not imposed. Some are workers in the silk, but most of them are working on the finer cotton goods in which New Bedford specializes. The bugaboo of southern competition does not scare New Bedford—yet. Competition comes mainly from Rhode Island and several Fall River mills whose costs are roughly comparable.

So eminent a textile authority as M.D.C. Crawford, style editor for Fairchild Publications, the trade authority, minces no terms on New Bedford’s manufacturers. Unprogressive, incompetent, backward, ill-advised, these are some of the epithets Crawford hurls at their heads. Labor Bureau, Inc., made a study of the economic conditions in the city, found workers averaging $19 a week, found mills profiting to the tune of $50,000,000 in the past 10 years; found profits at 11 per cent over a period of years; found mills grossly over-capitalized and still paying good dividends; found competition unimportant. These facts, checked by economists of the trade, are declared correct.

Will the strikers win? They will, if America’s workers admire fighting spirit, intelligence and stick-to-itiveness. They do, but it’s not easy to get the message of New Bedford over in a country 3,000 miles broad. In the meantime many a striker’s child goes to bed hungry in New Bedford and mothers sit long into the night, thinking and wondering. Mothers are mill workers in New Bedford.

The strike is a cold-blooded piece of business for William M. Butler and fellow members of the Wamsutta Club. They have piled up stocks to last them far into the summer. They own mills in nearby Taunton, still working. They have connections with mills in the Blackstone and Pawtuxet valleys, in neighboring Rhode Island. They’ll starve out New Bedford, cut wages, then other mill owners, pointing to New Bedford, will cut wages, then New Bedford will have to cut again “to meet competition.” Sounds fantastic? Not at all, for that’s what’s been happening in New England ever since those bitter days of 1921-22 when mill bosses first began wage-slashing.

The strikers must stick it out all summer, stick it out perhaps to Labor Day. Bosses will need production, they will be convinced by then that their “hands” have used their heads and mean business. The notices will be torn down and operatives offered their jobs back at the old wages.

A little money will go a long way in New Bedford to enable strikers to keep away from mills until Labor Day—and Victory. Good soup is nourishing, and now there’s lots of green vegetables, and soup meat is reasonable. Then outside New Bedford lies the broad Atlantic, teeming with fish. The “Portagee” are master fishers from the Azores, in their boats come tons of nourishment for the men, women and children of the strike.

Join U.T.W.

New Bedford is a job American labor can handle. It is possible, with good relief machinery—and New Bedford knows how to run relief machinery—for American workers to make victory certain for these 27,000 strikers and their 50,000 dependents. The Textile Council brushed to one side the only technical obstacles to outside relief, that of membership in the independent American Federation of Textile Operatives, by voting overwhelmingly to join the United Textile Workers. New Bedford workers have welcomed unity; other organized workers must make that unity mean something.

In these spring days, great white-breasted clouds drift in from the blue sea; strikers, freed from mill monotony, fish in nearby streams and in deep waters; young men and women keep trysts at the mill gates while they do picket duty; at Buttonwood Park thousands gather to hear reports from textile council leaders, to listen to famous speakers from distant cities, bringing substantial checks and messages of cheer. Merchants grumble about bad business; the street car company wails over lost income; mill magnates at the Wamsutta Club get glummer and glummer; children laugh and play near the mills, adding strength daily so that they too some day may take up the thread where mothers and fathers leave it.

In the many strikers’ clubs and relief centers, huge soup pots boil happily, sending cheery odors into the streets where kids gather with big buckets. Away go the kids, swinging steaming buckets, generous loaves of bread tucked under their arms. Here and there mill women, who do not understand the meaning of the strike, grumble and fret, threatening to go back. Other women upbraid them; the men look at the groups of arguing women from beneath shaggy eyebrows, the memories of many another long strike giving them a philosophic aloofness.

Just another strike? No, but a strike on which may hinge the future of all textile unionism in America, a strike in the best organized mill town in the country, a strike from whose victory will stream renewed hope and courage to a million savagely exploited textile workers from Maine to Alabama.

New Bedford’s great strike must be won.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v17n06-jun-1928-LA.pdf