An admirably thorough report on the background to, and events of, the 1926-27 rebellion against Dutch colonialism. Writing as Kjai Semin, Darsono, chair of the PKI from 1920-1925 who was exiled in Moscow at the time, also details what he sees as the weaknesses that led to its failure, as well as strengths of the rising.

‘The Uprising in Java and Sumatra’ by Kjai Samin from Communist International. Vol. 4 Nos. 6 & 8. April 15 & May 30, 1927.

THE uprising in Java last November, and in Sumatra at the beginning of this year, came as a surprise to many, even though it had long been awaited. A long time ago when the policy of suppressing the revolutionary peoples’ movement was intensified our enemies sensed that this must soon lead to an uprising. “Het Volk,” organ of the Social Democrats in Holland, which in the beginning wrote that the uprising was “Communist lunacy,” two weeks after the outbreak of the uprising had to admit that for a long time it had been anxiously awaiting for when it would finally break out. The late priest Van Lith, who was well-known in both Holland and Indonesia and for many years worked as a Catholic missionary among the population of Java, wrote in his book (which appeared in 1924), that no adequate native resistance was to be looked for in the coming Indonesian Parliament but that outside of Parliament the clash was being prepared for. This conflict is not a clash of leaders but of masses, which in the end cannot terminate otherwise than by the driving of the alien Dutch out of Indonesia.

This priest showed better comprehension of the sharpening of antagonism between the Dutch exploiters and the oppressed and exploited Indonesian masses of people than do the few Dutch Social Democrats to be found in Indonesia. Up to now, even after the uprising they are striving to smooth out these contradictions in a “lawful” manner. While the churchman stated that the fight against Dutch imperialism would be carried on outside of Parliament by the masses themselves, our peaceable Social Democrats are doing everything possible in order to hamper this extra-Parliamentary struggle; they seek to win over influential native leaders for collaboration with the Dutch Government in order thereby to water down the popular movement.

A Christian’s Report

Another Christian missionary, Dr. Kramer, who is so much of an authority on the field of the political tendencies among the natives that the government sought his services as a counsellor, states as his judgment of the native popular movement that, in all its shadings, it is an expression of protest, of resistance, of anger and criticism, either sharp and revolutionary or else working in secret. The situation was so serious at the time that this missionary added a warning: that the atmosphere was so charged as to threaten an explosion, and that its discharge had to be effected primarily by steps on the part of the powers that be.

Thus for a long time a revolutionary situation has prevailed in Indonesia. And the government was well-informed of it. Proof of this is seen in the fact that the State Attorney-General of Indonesia, who is at the same time Chief of Police, in April of last year issued a circular to the local authorities commanding them to hold the police and army in readiness because, in May, the Communists intended to organise strikes and disturbances of the peace. The arming of the European plantation employees was considered advisable. Doctor de Graeff, newly appointed Governor-General of Indonesia since September of last year, recognised the seriousness of the situation, the dangers which threatened Dutch rule. In his speech on taking office, he appealed for the confidence of all strata of the population. He could not bear any suspicions–he said suspicions paralysed his strength. The Nationalist intelligentsia, which at the time advocated a policy of non-co-operation, were regaled with the sweetest flattery so as to win over at least a section of the natives hostilely inclined towards the government, and thereby separate them from the mass movement.

The situation just before the outbreak of the uprising was a revolutionary one, and so it still remains although the uprising has been suppressed. The many lengthy reports in the Dutch-Indonesian newspapers prove that Dutch imperialist circles still view the development of affairs with apprehension. The increasing of the police and army, the equipment of policemen with rifles, the drilling of a section of the police to use hand grenades, the guarding of police stations with machine guns, the furnishing of white plantation employees with government firearms, the formation of Citizen’s Defence Rifle Societies–all these are signs that despite the increased terror which was instituted immediately after the uprising the revolutionary movement has not as yet been completely suppressed, that, on the contrary, its uprising is to be expected in a very short time. The class antagonisms in Indonesia have become so sharpened that the outbreak of a whole series of uprisings is inevitable, uprisings which will fuse into a broad insurrectory movement ending in the overthrow of the alien Dutch rule.

Influence of China

We must not forget another circumstance that has an extraordinary influence on the development of the revolutionary peoples’ movement in Indonesia. That is the Chinese revolution. Just as the Russian revolution of 1917 led to the creation of labour organisations in Indonesia and finally to predominant influence by the Communist movement there, so, beyond doubt, the victory of the Chinese Revolution will tremendously strengthen the movement for emancipation in Indonesia as well as in other colonies.

We believe that it is no exaggeration to say that the November uprising in Java and the January uprising in Sumatra will have the same significance as the revolution of 1905 had for Russia. Furthermore, in consideration of the present international situation, we may hope that the overthrow of Dutch imperialism will not be so very far off. Once we get this far, then the further development to the proletarian revolution will follow comparatively quickly.

It has already been established that the leadership of the insurrection movement in Java and Sumatra has been in the hands of the Communists. It may seem strange to many comrades in Western Europe that, in a colonial country like Indonesia, not the Nationalist but the Communist tendency has given its impress to the peoples’ movement. The Dutch Social Democrats also had to recognise the predominant influence of the Communist tendency. They hope, however, that this Communist “adventure,” as they call the uprising, will prove a turning point for the popular movement. “Het Indische Volk,” organ of the Dutch Social Democrats in Indonesia, writes (January 10, 1923):

“The fact that a political importation such as Bolshevism can develop here an independent party power greater than in any of the Asiatic countries proves that the native peoples’ movement here is in a juvenile stage, that it is split up and uncertain. Thereby it proves also its internal weakness. Moscow has also permeated British India and China, where it constitutes the inspiration for native, strictly limited, firmly-rooted movements. There we know nothing of independent Communist organisations with their crafty parallel organisations in the form of nuclei and disguises. There the Peoples’ Parties stand firm, they maintain their national peculiarity and expression. There Moscow is being used as a whetstone for their own forces, which for the most part are not displaced by a Communism imported from abroad. Only a lack of native Indonesian intellectual forces for an independent struggle for our national ideal could lead to a condition in which the masses finally fell into Communist hands, so that Moscow was able so easily to inflame the organisations of the thinking section of the nation.”

Right Wing Admissions

When, in 1918, the Left Wing of the Social Democracy in Indonesia wanted to proceed with the formation of proletarian fighting organisations, the Right Wing maintained that organisations of this kind could not be formed because the working class of Indonesia, and especially that of Java, was still too undeveloped. In 1920 the Left Wing of the Social Democracy formed the Communist Party, which has shown the Social Democratic gentleman clearly that there certainly is room in Indonesia for a vigorous proletarian party. Shortly before the uprising the Social Democrats also recognised this. In reply to an article by a writer who stands close to the Social Democracy and who maintained that in Indonesia Socialism could not be introduced without passing through the period of West European capitalism, and consequently that in Indonesia at present a national struggle rather than a class struggle is possible, the editors of the “Indian People,” the organ of the Dutch Social Democrats, wrote the following:

“Modern capitalism was born and bred in countries in which industry could and did become the chief and natural source of existence of the people. Agrarian states produced a different capitalism and Socialism of their own. Now if Mr. W. will recognise that here the more-than-rich soil, with its barely touched potentialities, furnishes an agrarian basis for the economic life of the great masses of people, upon what basis then rests the cocksure statement that passage through a western capitalist period is inevitable?”

“We ourselves must differ, not expecting Orientals to become Socialists according to the western ‘models’; we must teach them the essence and power of capitalism together with that of Socialism. It is up to them what use they will be able to make of the lessons under colonial conditions, how they will work up what they have learned, in order to build up a Socialism that corresponds to their own society and their own social life. What is to grow out of it cannot be dictated by any European.”

This recognition by the Social Democrats came only after we had brought proof that in Indonesia a proletarian movement is not only possible but necessary for the successful combatting of imperialism.

Let us look more closely at the factors which make it possible for the Communist tendency in Indonesia to march at the head of the whole peoples’ movement.

The Economic Factors

The Indonesian Islands contain various stages of economic development. Yes, there are even areas in which there can be no talk of any economy whatever, as e.g., in New Guinea, where the natives still live a nomadic life, and where cannibalism still prevails. One can hardly conceive of a country in which such variegated stages of development are to be recorded as in Indonesia.

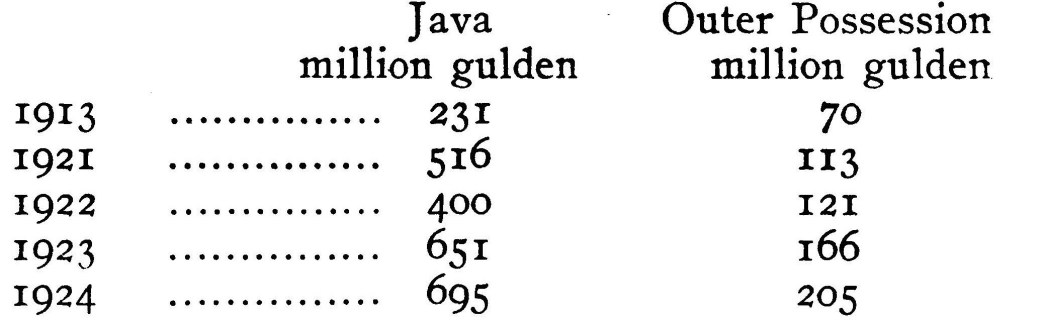

Economically the most advanced part of Indonesia is the Island of Java, which in 1920 had a population of 35 million. According to latest estimates, Java has now about 40 million inhabitants. The Islands of Sumatra, Borneo, Celebes and the other smaller islands and a part of New Guinea, which are usually collectively called the “Outer Possessions,” in 1920 had 14 million inhabitants altogether. It is the extremely dense population of Java which drives this island rapidly forward economically. The economic start that Java has over all the remaining islands together, is clearly shown in the following figures taken from the annual report of the Java Bank. These figures give the export of agricultural production from big capitalist enterprises, such as sugar, rubber, quinine, coffee, tea, tobacco, cocoa, etc.

The big capitalist agricultural enterprises in Java, which constitutes only one-thirteenth part of Indonesia, therefore exported in 1924 more than three times as much as all the other islands put together.

Agricultural exports of the natives, in comparison with the total agricultural exports, amounted to:

These figures show clearly that in Java native producers have been largely crowded out by the big capitalists, which are more and more taking first place. Whereas the figures for Java show this tendency to crowd out still further the native producers, the “Outer Possessions,” especially Sumatra, up to 1924 still show a tendency towards the further development of native economics. At present, however, there are many signs that the native producers in Sumatra also are being pushed to one side by the advance of foreign capital.

Agricultural industries are now the most important in Indonesia; their exports in 1924 amounted to more than 70 per cent. of the total exports. Of these industries sugar production is the most important, its exports in 1923 amounted to 36.5 per cent. and in 1924 to 32.1 per cent. of the total exports. This sugar industry is located only in Java and is carried on scientifically. The sugar yield per bouw (7,200 sq. metres) in Java is more than double that in Cuba.

Peasantry Hard Hit

How rapidly the Javanese peasantry is disintegrating, due to the advance of foreign capital, is shown by the following figures:

The number of villages in Java sank from 29,518 in 1882, to 21,539 in 1922; in these forty years the amalgamation of the smaller villages into larger has been in process. Notwithstanding this we see, alongside a reduction in the number of villages with purely communal landownership, an increase in the number of villages with purely individual landownership; this proves that rapid changes are taking place in the conditions of the villages. The increase in the number of villages with purely individual landownership takes place only at the expense of those with purely communal ownership. These changes have, of course, been accompanied by a disintegration of a part of the peasantry.

In 1923, there appeared an official report on the “Results of the Investigation on the Tax Burdens upon the Population of Java.” According to the figures contained therein the 1924 population of Java–a population figure of 35 millions in 1920 is taken as a basis for the estimate had an income of about 1,500,000,000 gulden annually, that is, 52.86 gulden annually per capita. A family of five would, therefore, have an annual average income of 214.30 gulden or 4.12 gulden per week (about seven shillings).

But even these figures seem to be somewhat too rosy. “Hamburger Nachrichten,” a paper interested in imports into Indonesia, wrote as follows, in connection with the report of van Ginkel, who was authorised by the lower chamber in Holland to investigate the economic situation of the population:

“The van Ginkel Commission, which was officially authorised to conduct an investigation into the economic situation of the Javanese population, has made a report that amounts to nothing less than an indictment against the government of the Dutch Indies. The efforts of the report to make everything appear in a better light are rendered futile by the statistical data on the income of the population. According to these figures the average income of a Javanese family of five in the wealthiest districts is 225 gulden per year, on which the government levies 10 per cent. in taxes. Even taking into consideration the fact that the Javanese require very little clothing, very simple household utensils and furniture, this income is nevertheless miserably low. In Sarang (West Java, where the uprising broke out) this average income amounted to 185 gulden, and in Djokdja (Central Java) 21.16 gulden per capita annually (less than three shillings per month). From this the taxes, rent, food and clothing must be de- ducted. In the densely populated district of Surakarta, where two million people live, the annual average income per capita amounts to 39 gulden (45 shillings).”

Another representative of the importers, H.L. Haigton, in the “Handelsberichten,” expressed himself as follows on the poverty of the masses of the Javanese people:

Heavy Taxation

“In order to reckon with the circumstances unfavourable to imports one must bear in mind the very small purchasing power of the natives, who receive a daily wage on the plantations equal to an hour’s pay for a worker here (in Holland), The capital owned by the natives in Java, with very few exceptions, is insignificant. The existence. level of the Javanese can be characterised as follows: To live from day to day-and even this very badly.'”

“De Courant,” a liberal Dutch newspaper in Java, had to admit in an article “Unrest and Well-being” that although the so-called head-tax which is considered very unjust by the population had been repealed, the other taxes still weigh very heavily upon the Javanese peasants. According to the statements of this newspaper the peasant must often pay out 25 per cent. or more of his income in taxes. The paper then continues:

“But from the exact figures on these cases we may unreservedly draw the following conclusion: “A part of the village population of Java (we hope that it is only a small part) is so reprehensively taxed and must, therefore, live on such a very minimum income, that it has nothing to lose in an uprising against the State except its life, and this a life full of misery, care and penury, a life to which most of us would attach little or no value.

“It is, therefore, no wonder that the Communist leaders, especially in the villages, could win thousands of supporters who were ready to wage an armed struggle against the representatives of the State.

“The repeal of the poll-tax in 1927 undoubtedly brings a certain relief to many, but figures to be found in this connection in even the latest official reports show clearly enough that the repeal of this poll-tax means only a very slight improvement in the living conditions of the village population.” This is how the importers’ agents in Indonesia size up the position of the broad masses of the people, a judgment which we may appraise as a devastating condemnation of Dutch imperialist maladministration of Indonesia.

Cheap Labour

The incessant impoverishment of the broad masses of the Javanese people makes this island a catch-basin for cheap labour power, as is the case in South China. To a certain degree one may say that, in Indonesia, Java is the country of wage-labour and the remaining islands of the peasantry.

The impoverishment of the masses of the people has only proceeded with great rapidly since the outbreak of the war. The tremendous increase in prices of foodstuffs forced many to dispose of their last remaining inheritance. The impoverishment of the native petty traders began in 1920 when the crisis broke out. The mass dis- charges and wage reductions of workers and employees cut down the potential market of the tradesmen who were wont to satisfy the needs of the masses. The government dealt a very severe blow to these petty trading elements by introducing new taxes and by extraordinarily increasing the existing ones. These hit not only the petty traders but also the remaining peasant strata. The pauperisation more and more included all the population. This favoured the sprouting of an anarchistic tendency in the Indonesian peoples’ movement which ex- pressed itself in assassinations. In 1923 the first political bombs were thrown at the Governor-General of Indonesia, who was viewed as the prime mover of all this misery. Since then bomb attacks and other attempts have been the order of the day.

The disintegration of the petty bourgeois strata in Java finds its expression in the marked decline in 1923 of the once powerful mass society, Sarekat Islam. The decline in membership resulted, in 1923, in the dissolution of the serious popular revolutionary National Indian Party, the party of the revolutionary intelligentsia, which at that time represented the most revolutionary tendency in the peoples’ movement. The leadership of the Communist Party, since the end of 1923, is simply the expression of the proletarianisation of the broad masses of the people and the further sharpening of contradictions between Dutch imperialism and the pauperised masses.

Communist Leadership

The leadership of the movement which the Communist Party of Java has won for itself, was the reason why the suppressed peasants of Sumatra, Borneo, Celebes and the other islands also saw in the Communist Party the only party able to lead them successfully in the struggle against the Dutch oppressors.

In Sumatra, which is 3.6 times as big as Java, and in 1920 had 6 million inhabitants, our Party had considerable support. Sumatra occupies second place in Indonesia; and for capitalism it is the land of the immediate future. Peasant economics and small enterprises still predominate here. In South-western Sumatra in 1925 a small section of the population got rich quickly, due to the very high prices of rubber. Plenty of plantation sites are still to be had here; only labour power is not sufficiently abundant. The capitalists import this from China and Java. At present about 300,000 indentured workers are forced to labour under the worst imaginable working conditions.

In addition to plantations there are in Sumatra coal and gold mines and a modern oil industry. In order to accelerate the economic development of the island, the government is proceeding to build railways and roads at a rapid rate. The quick progress of economic development in Sumatra can be seen from the fact that, in a period of 12 years, capital invested in Eastern Sumatra has more than doubled, it has increased from 207 million gulden in 1913 to 440 million in the beginning of 1925. Of this 52 per cent. is Dutch and 48 per cent. foreign, particularly British (which holds first place in rubber production).

The Backward Isles

Dutch Borneo, which is four times as big as Java, in 1920 had a population of two million, and is, therefore, economically still very backward despite the large modern oil industry. As in Sumatra, a small portion of the population has enriched itself in the rubber trade.

Celebes, one and a half times as big as Java, in 1920 had a population of three million. As in Borneo, capital has not yet penetrated very far. Production for own needs still plays a very important role here. Since 1923 a short stretch of railway has been in operation.

The other Indonesian islands, with a few exceptions such as Bali and Lombok, are even more backward than Sumatra because of the sparse population, small size and slight fertility of the soil.

The advance of capitalism in Sumatra, Celebes, Borneo, etc., and a shortage of labour power, necessitate special ways and means by which the peasants can be dragged into work. It frequently happens that because of this forced labour the peasants are not able to cultivate their own fields, with the result that harvests fail and famine is the consequence.

The uprisings which have repeatedly broken out in the “Outer Possessions” find their explanation in this unpaid forced labour.

Such is the economic picture of the most important Indonesian Islands.

SINCE 1917 the fight for better wages, the class struggle, has entered into the forefront of the national movement. Our Party was changed into a Communist Party in 1920. It was first called the Indian Social Democratic Union. The native comrades then worked in the existing national-religious mass union “Sarekat Islam.” Our demands for economic improvements in the conditions of life of the working-class masses were welcomed with great approbation. influence of our comrades increased and this led to the exclusion of our comrades from the Union by the leadership. In 1923 came the split. The Left Wing, which comprised the great majority, went with us, forming later the “Sarekat Rajat,” that is, “the National Union.”

Our party, which stands at the spearhead of the strike movement, won the sympathy of the masses in an ever increasing degree, and against it the Government used increasingly drastic terrorist methods. Through this the Party became the leader of the National Revolutionary Movement.

On the 13th November, the revolt broke out in West Java. It was the first time in Indonesian history that the masses entered into a struggle for political ends. The “most patient and most meek people of the earth,” as the famous Dutch writer, Multatuli, called the Javanese, grasped their weapons to free themselves from oppression. What an ideological conversion must have occurred among the masses. What a mismanagement the Dutch Government must have exercised, that even the patient Javanese lost their patience!

The November rebellion in Java was followed in January by one in Sumatra. The Dutch newspapers cried that the revolts were directed and financially supported by Moscow; now the Dutch police have themselves the proofs to hand, that the revolt is organised in agreement with the masses, that the underfed, starved inhabitants of Java have given their money to buy arms in order to overthrow the Dutch government. We shall see what consequences the revolts will have on Dutch imperialism.

The comrades who led the revolt did the best that, under the extraordinarily difficult circumstances, could be done. Still, a few mistakes were made, which must be exposed in order to make possible a successful fight in the future.

Strong Points of the Revolt

Our judgment rests on reports and articles in the Dutch press. At the moment other sources are not at our disposal. The strength of the revolt lay in the fact that before it occurred almost all sections of the population regarded the revolutionary movement without enmity. With the exception of a few corrupted elements among the natives, the revolutionary movement, wherever Communist influence was preponderant, won all sympathies. Even the Chinese, of whom in Indonesia there are nearly a million, followed the development of the Indonesian national movement with the greatest sympathy. “Sin Po,” which is accounted the most influential Chinese paper in Indonesia, and is read by many of the natives, demanded early in 1926 that the Chinese support the native national movement not only morally but also materially.

As for the plan of the revolt, this, too, was well worked out, as the Dutch newspapers themselves admit. And yet the extent of the revolt was not so great as our comrades expected. In a few districts the defeat was ignominious, of which our comrades never dreamed. In the capital, Batavia, there was no talk of a serious fight with the armed forces. After four or five days the movement in the capital was finished. In the villages of Bautam and West Sumatra, on the contrary, there were serious struggles to record. Here the fight lasted about a month.

Why was it that in the capital, where the working-class is found, the fight ended so quickly? What was the cause of the struggle being so long maintained in the villages of Bautam and later of West Sumatra? Our Party has a great influence among the population of Batavia. A few days before the outbreak of the rebellion more than 10,000 persons in Batavia handed in their membership cards of our organisation, the Sarekat Rajat, because of the threats and compulsion of the police. One can, therefore, suppose that the actual membership of the Sarekat Rajat in Batavia must be much greater. And yet from these thousands perhaps only a few hundred took part in the movement. In the villages on the other hand all the villagers took part in the movement, whole villages were deserted by the male population who had left to take part in the struggle.

Why Did Not Revolt Spread?

Why did not the revolt spread immediately to Middle and East Java, where the discontent of the masses is not less great and our organisation has also a very powerful influence?

Many leading comrades were arrested and a few exiled some weeks before the outbreak of the rebellion. Among these comrades were, perhaps, those who had helped in the working out of the plan of revolt and had carefully studied the details of its execution. Those who are left, of whom many were still quite young, were compelled to carry through the revolt mechanically. This explains the fact that before the outbreak of the revolt no slogans were issued. This explains the fact that a small group of comrades occupied and held the telephone centre, instead of leaving this immediately after the destruction of telephone communications.

They knew that the occupation could not last long–not even a few hours. And yet it appears that the comrades did this. In another quarter of the town, a different group made an attempt to seize the prison, which was guarded by soldiers. All these attacks could not carry along the masses of the town population. In Batavia and in other towns such as Tjiamis the movement was isolated from the broad masses of the people. The police supervision and the measures that they took in the towns were so sharp that the contact between the leadership and the masses was not close. The military and police forces were concentrated in the towns. The heavy blow which the first attack met with frightened the masses of the people and discouraged them from further struggle.

The conditions were different in the villages. There the persecution against our organisation could not be introduced so sharply. There are more or less friendly relations between the village police and the village inhabitants. The town police receive their upkeep from the Government, while the village police receive theirs partly from the taxes raised from the population.

Just as the town police is a paid tool of the State, so the position of the village police is a reflection to a certain extent of the misery or welfare of the villagers.

There is to a certain extent community of interests between village police and the villagers. This alone would be sufficient to explain that the police themselves took part in the revolutionary movement in the villages, particularly in West Sumatra, where, on account of the patriarchal conditions, the contact between villagers and police was strengthened by family relationship. Sumatra it went even further. There many, even of the State officials, as the Dutch newspapers wrote, participated in the organisation of the uprising. A high native official even informed a leader of the rebel movement about the movement of troops. This close relationship is an indication of the isolation of the districts. The more backward a place is economically the more friendly are usually the relations between the masses of the people and the administrative officials. (An official who was too devoted to the Government was frequently set aside. This was one of the most favourable factors for the organisation of the uprising.) The lack of good means of communication in such places considerably favours the fighting operations of the rebels. Moreover, the presence of many forests lightens their struggle.

In North Sumatra the guerilla warfare against the Dutch military has been going on since the end of 1925, and is not yet quite finished.

Soldiers and Police

Our comrades reckoned on the refusal of the soldiers and police to comply with the orders of their superior officers.

There was no talk of a very extensive refusal to serve. And still we must believe that hope in this respect is well justified, since before the uprising many soldiers and police were dismissed on account of their revolutionary opinions.

In the court proceedings, the comrades declared that the police and soldiers who were in agreement with the revolt were to have secret signs, so that only those soldiers and police should be attacked who did not know the password.

That so few of these soldiers and police took part is explained by the fact that our comrades in the towns could not carry along with them the broad masses, which was so necessary to make an impression. Still the soldiers do not seem to be entirely untouched. As a Dutch paper “Java Bode” reported, many thousands of cartridges were fired in Bautam, but the number of dead and wounded on the side of the rebels was so small that we can believe that the soldiers shot into the air. The soldiers and rebels placed themselves at a distance of from 10 to 20 metres from each other, so that the former could have massacred many if they chose. In Surabaja 14 police were arrested immediately after the outbreak of the uprising because of their revolutionary opinions.

Both in Java and Sumatra telephonic and telegraphic communications were cut through and railways lines broken up. In Middle Java tobacco sheds were set on fire.

In order to support the revolt the General Strike–at least the strike of the transport workers-was not proclaimed. Such a strike would have strengthened the whole movement. This was one of the greatest mistakes that were made.

The conditions were very favourable at the beginning. The authorities were taken completely unawares by these events. So surprised were they, that they did not know where to begin. According to the Dutch newspapers, about 600 soldiers were drafted into Bautam to fight the rebellion. The authorities did not dare. to send more military forces there because they feared that rebellion might also break out in other parts of Indonesia. The Government was in the beginning in the greatest confusion and was still in doubt whether their men could be quite depended upon.

These favourable moments were allowed to slip by unused.

A Great Mistake

Another great mistake was that the outbreak of the revolts did not occur at the same time. In West Java it happened on the evening of the 12th-13th November. In Middle Java the first unrest broke out a few days. later. Meanwhile, the leading comrades were arrested on the 13th and 14th November. Still later the rebellion broke out in Sumatra. There the uprising began only on the 2nd January, that is two months after the out- break in Java, where the revolt was already crushed to a large extent. On account of this it was easy for the Government to send soldiers to West Sumatra. Moreover, through the defeat of the movement in Java, the soldiers became more docile to the Government.

This lack of simultaneity in the outbreak of the revolt helped the Government to win an easy victory and strengthened them morally. Our ranks became weakened and disorders were the consequence, disorders which cost us many sacrifices. When we entered into the fight, the circumstances were favorable. The Government had at its disposal only somewhat more than 30,000 soldiers and just as many police-against a population of 50 million. About 90 to 95 per cent. of these forces were natives, whom we could easily have brought under our influence, if such great mistakes had not been made in the carrying out of the plan of revolt.

As our forces received such heavy blows, the masses transferred their support. If before the revolt they were with us, later, out of fear, they went over to the soldiers against our comrades, many of whom were delivered up to the soldiers by the intimidated villagers. This occurred not only in Java but also in Sumatra.

It must be taken into account that conditions in Indonesia, particularly in Java and Sumatra, are quite different from those in Europe. There, there are no great towns, where millions of people are concentrated. The millions of Javanese are found in the villages. In our future fights we must take care that, if the fight in the towns is to end successfully, this fight must first be begun in the villages and on the plantations, in order to bring about the deconcentration of the military and police forces. By that the defence of the towns will be weakened and their taking over made more easy.

In the villages and plantations it is much easier to mobilise the masses against the organs of the State and the servants of the employing class, because there the forces of the police are quite insufficient, and it is easy to win victories at the very beginning, victories which are essential to enthuse the masses and carry them along.

Lessons of Defeat

We have suffered a defeat, but we must draw the lessons of this defeat. To recapitulate, we can say that the strength of the uprising consisted in:

1. The ideological preparation was good, our organisations were assured of all sympathies.

2. Our opponents were at first in doubt as to whether their instruments of power were reliable.

3. Until the last moment the Government did not know that a revolt was to break out. This shows that the Government could not or only to a very small extent could corrupt our forces, which is a very good omen for the future development of the revolutionary national movement.

The weak aspects of the revolt were:

1. The execution was incomplete, the cause of this being the arrest of many leading comrades before and just after the outbreak of the rebellion, so that the movement of revolt could not be quickly extended on account of the lack of leading forces.

2. The comrades issued no slogans before the uprising which would speak clearly to the masses of the people and rouse them and carry them along with the rebel movement.

3. Instead of the uprising being begun in the villages, to effect the disintegration of the soldiers and police who were concentrated in the towns, the comrades at once took up the fight against the concentrated forces in the towns, as a result of which they were beaten in their first attack, and the masses of the people were intimidated. The first day after the outbreak of the revolt, the Dutch capitalist newspapers went off their heads with excitement and alarm; a few even demanded that whole villages be wiped out. Even the Dutch Social Democrats in Indonesia threw off their masks and showed themselves during and after the rebellion as the most vile lackeys of imperialism. They knew that for the masses of the people there was no other way out than a rebellion; they knew that the policy of Dutch imperialism had so sharpened the contradictions that the result had to be a rebellion, and in spite of that they condemned the revolt and characterised it as a creation of Moscow. As before the uprising, the Social Democrats snatched this opportunity as a favourable moment to stir up the native intelligentsia against us. They demanded of them that they should organise the masses of the people to prevent the employment of these pernicious revolutionary methods. They further demanded that the native intelligentsia should give up their policy of non co-operation, and occupy themselves politically with work in the out-and-out reactionary representative bodies.

Corrupting the “Nationalists”

The Social Democrats had a few successes to be noted. Their propaganda work among these politically unripe sentimental native intellectuals, who choose to call themselves rationalists, has made many of them into traitors to their people. Dr. Sutomo, the distinguished president of the Study Clubs in Surabaja, who a month before the rebellion declared at a meeting that Communism, whether among the native aristocracy or among the intellectuals who stood behind them, carried on a highly important struggle, because Nationalism lived strongly among them, this man who in 1925, withdrew from the municipal council in order to manifest his “non- co-operative” opinions and his indignation against the Dutch Government, the same man committed, after the defeat of the revolt, the greatest treachery, in that he declared before the court that the revolt was organised in agreement with the Nationalists. When he heard that the Government wished to increase the army and the police, he immediately solicited the posts of officers and police commissioners for the intellectuals, so that the natives might share the responsibility with the Dutch.

He was, however, maintained as President of the Study Club because the members were of the opinion that the part he took in the revolt did not violate the principles of the club.

And the Intellectuals

The Social Democrats continue to win over and corrupt the intellectuals. At the end of January, at a meeting in the premises of the Study Club in Surabaja, Stokvis, the Social Democrat, said (after having condemned the rebellion) among other things, the following:

“Supposing, however, that the Communists had, through the strength of their weapons, that is through their number, been victorious over their opponents, what would that have achieved politically? Nothing that could bring any advantage to the Indonesian peoples.

“If the Dutch sovereignty were overthrown, the consequence would be that Indonesia would be flung into the Asiatic jumble as the richest and weakest, the most coveted and the least powerful unit.” Stokvis cried to the intellectuals:

“Think of this, that with these methods [with revolutionary methods-K.S.] you strengthen the reaction and the might of the strongest. The Communist plots have achieved this, that now dozens of millions will be drawn from the State Budget for increasing the army and the police, money which otherwise could be used for other purposes, which lie more in the interests of the people.”

How different is the attitude of the Chinese in Indonesia! The great majority of them are born in Indonesia; they are largely small dealers and workers who mix daily with the natives. Moreover, the Chinese in Indonesia are placed legally in the same position as the natives, not with the Europeans as is the case of the Japanese and Siamese. They have the same legal standing as the natives and the police can worry them just as they can the natives.

At the foundation of the “Sarekat Islam” in 1913. there was sharp opposition between natives and Chinese, because the former considered the Chinese as the cause of all the misery of the natives. It is owing to the work of the Communist Party since 1913 that this enmity now no longer exists, and in its place there is friendship. And since then this friendship has become even closer. The Chinese newspapers and many Chinese supported our organisation not only before the rebellion, but also after; when our Party was attacked from all sides, it was the Chinese newspapers, who were not at enmity with our Party; particularly the most influential of them, “Sin Po,” which a year before had urged the Chinese to support materially our movement, wrote on November 27th, 1926, inter alia, the following.

A Chinese View

“All Dutch newspapers are of the opinion that the Soviet has its hand in the great unrest in Java. They wish to put the whole-or the greatest part of the blame on Moscow. Moscow is the instigator, Moscow supplied the weapons, etc. etc. It would be better if they sought all the causes of the revolt here in the country itself, and not put all the blame on others. Every sober judge must realise that it is unthinkable that the uprising is merely a consequence of Moscow’ agitation.’

“All great events are conditioned by many causes, and it is much more important to ascertain these than to bark at Moscow or Canton, like a dog yelping at the moon.”

This friendly attitude towards the Indonesian national movement is caused by the influence of the events in China.

In the last few months hundreds of Indonesian-born Chinese have gone to Canton to work in the Cantonese army, in spite of the threats of the Dutch Government that those who have gone to Canton will not be allowed to return to Indonesia.

There are, therefore, many reasons to induce the Chinese in Indonesia to work together with the natives of Indonesia.

Of all the parties in Indonesia, it is only the Communist Party which has made any extraordinarily great sacrifice in the Indonesian movement of liberation. It is only the Communist Party which has propagated and taken up the consequences of the revolutionary fight against Dutch imperialism. It is also the Communist Party which has given the masses a clear programme and lead.

Communists have led the many strikes and brought the masses ideologically under their influence in a systematic fashion. The leaders of the other organisations have betrayed the masses.

Will Strengthen Communism

As, for example, Tjokroaminoto, the Chairman of the “Sarekat Islam,” who shamefully betrayed those who took part in the conflicts with the police in 1919, and cringed to the court in order to get out of his punishment. The attitude of our comrades before that court also shows the masses that Communists are not frightened away by the most grave consequences, if it serves to protect the interests of the workers. The trust of the broad masses of the people in the Communists is so great that they could lead the uprising.

The conditions and methods of struggle in Indonesia, particularly in Java, bear so great a resemblance to the pre-revolutionary conditions of Russia that a Russian doctor who has lived in Java many years, called the Javanese “brown Russians without beards.” Communists led many unsuccessful strikes but in spite of that the faith of the masses in our Party was not shaken. As the unsuccessful railway strike led to a strengthening of our Party, we may well expect that the revolt in Java and Sumatra, although a failure, will not shake but strengthen the ideological influence of the Communists.

The life of the masses of the people in Indonesia, particularly in Java, is so wretched, that they will be compelled even further to fight along revolutionary lines to improve their conditions of life. According to a calculation which we quote from the “Economic and Statistical Report,” the most important taxes in Indonesia, such as the import and export taxes, the duty on killing cattle, the poll tax, income tax (for natives) and other taxes and excises for 1927 will bring in 158.6 million gulden, of which 148.9 million gulden will be raised from the natives. This is an indication of the intense exploitation of the masses of the people by the Dutch Government.

The Poll Tax

This year the so-called poll tax, which is felt to be most unjust by the population, because the town population do not have to pay it, will be abolished. This abolition will lessen the State income by 12 million gulden. The Government is, therefore, seeking to recompense itself by increases in indirect taxation. 1926 decreases in taxation for 1927 and 1928 were promised. The increase of the army and police force after the uprising will, however, make this reduction in taxation impossible. This means that the masses of the people will be further oppressed just as in the previous year, or perhaps even worse.

The present Governor-General of Indonesia, Dr. de Graeff, is a former Dutch Ambassador in Tokio and Washington. The appointment of a diplomat as chief of the Dutch imperialist state in Indonesia is no accident. This appointment is an indication of the fact that there are many difficult problems of foreign policy appearing in the East, which are dangerous to Dutch supremacy. Holland usually appoints diplomats to the Governor-Generalship, if the problems of foreign policy are such as affect her empire, as was the case during the war, that time Dr. Van Limburg Stirum, also a former Dutch Ambassador in Tokio, was appointed Governor-General of Indonesia. The present chief representative of Dutch imperialism, Dr. de Graeff, has, however, no luck. His gentle speeches make not the slightest impression on the masses of the people. Two months after he entered office the people of Java and Sumatra rose in revolt.

Both internal and external politics are now just as dangerous for Dutch supremacy. The Government is trying to solve the former problems by terror, by sentences of death, by extraordinarily heavy punishment and sentences of exile for the Indonesian leaders of the national movement to New Guinea. For all that the revolutionary nationalist movement of Indonesia is not crushed. The Government may be able to corrupt dissolute intellectuals, the great masses will carry on the fight. Communist influence has already found anchor in the hearts of millions.

Situation still “Dangerous”

That the Government officials themselves consider the present situation as extremely dangerous is shown by the interview given to the Dutch paper, “Java Bode,” by Wolter beek Muller, the Chief Public Prosecutor of Indonesia, who will shortly go into retirement.

This man is Chief of the Indonesian police. said about the Communist organisation: “As far as the Communist movement is concerned, it was best defined by Dr. Talma [Chairman of the Sugar Syndicate in Java.-K.S.] in the National Council, ‘the Communist movement is like a wave which recedes only to advance anew with greater force!’ That is also my opinion. The events of last year gave us sufficient experience to justify this description.”

Class distinctions have been sharpened to such an extent during these last years that rebellions must continually repeat themselves. On the one side there are the most modern big plantations, and on the other side millions of poor peasants, small merchants and coolies. The petty bourgeoisie which fights in Europe by its wavering alliance usually, as with capitalism against the revolutionary masses, is here not so strong. “Indian Courier,” the organ of the European employees in Java, wrote on April 7th of the past year as follows:

“Where such a class is absent, as is the case here, the Communist danger remains threatening, and it cannot be fought by temporary measures.”

In 1924 there were signs of the formation of a powerful native petty bourgeoisie in a part of Sumatra and Borneo owing to the extraordinarily high prices received for rubber. But the Dutch capital invested in rubber, which is controlled by finance capital, does not tolerate any competition, and desires to keep all the profits of the rubber industry for itself. Thus many tricky methods are employed in order to retard the development of the native traffic in rubber.

The final destruction of the native rubber producers will not be long in coming. The power of finance capital in Indonesia is so enormous that it is able to crush any improvement in native business and will unhesitatingly do so.

The penetration of foreign capital in Indonesia was so rapid that the retransformation of classes is being brought about very rapidly in Java as well as in other islands of Indonesia. Owing to this, the appearance of a definite ideology such as the petty bourgeois in Western Europe which could retard a revolutionary movement is not possible.

That the Dutch Government understands the gravity of the position very well is clear from the fact that they are not only going to increase the army and the police, but are also deconcentrating the army in order to be able to tackle a revolt quickly, should it occur. Just as, before the revolt, the army existed more to defend the country against outside enemies, so now it will be used. as a weapon against the enemy within.

Influence of China

As the revolution in Russia inspired that in China, so the Chinese revolution and its victory will drive forward powerfully the Indonesian national movement, The Indonesia has serious struggles before it. Indonesian masses can emerge from these struggles only as victors if there exists in Indonesia, although illegally, a Communist Party with Marxist leaders. Our Party has imparted a revolutionary tradition to the masses of the people, which will not easily disappear. The lost prestige of Dutch supremacy will do the rest in revolutionising the masses.

For this reason also, that there is danger of war in the East, it is necessary that the rebuilding of the Communist Party in Indonesia should be immediately taken up, so that in future it will be capable of changing an imperialist war into a war for freedom against Dutch mastery.

The first stage of the revolution in Indonesia, as in China, will be the overthrow of imperialism.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-4/v04-n06-apr-15-1927-CI-grn-riaz.pdf

PDF of full issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-4/v04-n08-may-30-1927-CI-grn-riaz.pdf