Another considered intervention from a young Louis C. Fraina. Here, in the midst of the First World War, Fraina rebukes the ‘social-imperialism’ Heinrich Cunow and his U.S. co-thinker Ernest Untermann, tracing its roots to a revisionism that had made class peace long ago.

“Revolution by Reaction” by Louis C. Fraina from New Review. Vol. 3 No. 15. October 1, 1915.

IT is no unusual thing for a revolutionary and revolutionizing scientific theory to be transformed into a prop of social reaction, the simplest illustration being the Darwinian theory of the “survival of the fittest,” which was used to justify competitive Capitalism and its laissez-faire philosophy. Obviously, if this transformation occurs in the domain of natural science, it occurs oftener in the domain of social science, the most complex of the sciences. The doctrinaire Socialist may consider the parallel inexact. He conceives Socialism as a sort of super-science unaffected by the conditions which affect “bourgeois” science. This illusion has an apparently materialistic basis. The doctrinaire Socialist assumes that there are no class divisions within the proletariat, its interests being one; and that, accordingly, Socialist theory possesses a unity of thought impervious to reactionary influences. If this assumption were correct, the sharp disagreements among Socialists would appear a product of insanity or worse. But the assumption is not correct. The immediate interests of the proletariat are not one; it is split by class divisions; and Socialist theory is not only susceptible of reactionary interpretation, but is being used for reactionary purposes by powerful groups within the movement.

The student of Socialism is aware of how certain aspects of Socialist theory are being distorted. The brilliant concept of the materialistic conception of history, with its full-orbed recognition of the non-economic factors involved in the social process, has in some quarters been distorted into a rigid and preposterous “economic determinism,” emphasizing an exclusive and personal economic interest as the determinant of social action. The direct actionist bases his apotheosis of violence upon the Marxian generalization, “Force is the mid-wife of the old society pregnant with the new;” while the pure-and-simple political actionist uses the generalization, “Every class struggle is a political struggle,” as the justification for an exclusive emphasis upon politics as the tool of the revolution. It is unnecessary to pile up illustrations: they are numerous and familiar.

These distortions of Socialist theory, however, might be dismissed as the consequence of error in interpretation, or simply of downright ignorance; although the controversy over direct action and political action springs largely from divergent group interests within the Socialist movement. They are clearly not in a class with the transformation of the “survival of the fittest” theory into a prop of reaction.

It is different with the subtle transformation of Socialism from a revolutionary into a conservative social force. Where Socialism previously attempted to express the interests of the proletariat as a whole, the Socialist movement now generally expresses the interests of the skilled portion of the proletariat and the lower middle class. This change has been crowned by the transformation of the Socialist movement into a movement of social reform, and the transformation of official Socialist theory into a theory of State Socialism. This is indeed the transformation of a revolutionary and revolutionizing theory into a prop of social reaction, insofar as the interests of the unskilled proletariat and revolution are involved.

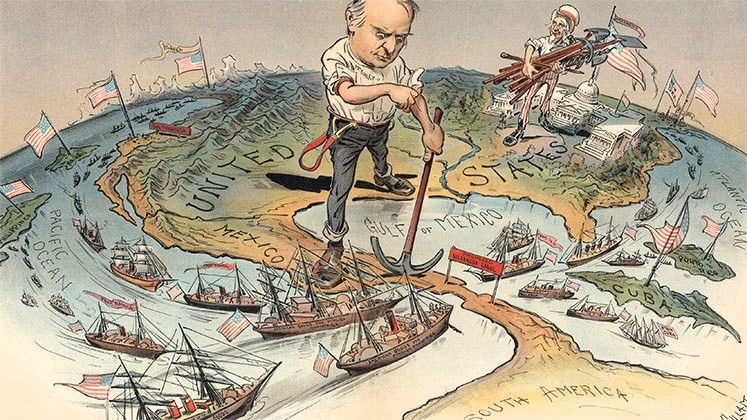

The war has accelerated this transformation of Socialism. We are now witnessing the astounding phenomenon of Socialist theory being used to justify Imperialism, and all that Imperialism implies–Imperialism, as being in the interests of the proletariat and revolution. I do not refer merely to the German Socialists who politically support Germany’s plans for conquest, but to the theoretical defense of Imperialism made by such an honest and cogent thinker as Heinrich Cunow. This clinches the parallel: as the “survival of the fittest” theory was used to justify competitive Capitalism, Socialist theory is being used to justify Imperialistic Capitalism.

Cunow maintains, rightly, that there will be no immediate collapse of Capitalism and no early victory of Socialism; that illusions arising out of this belief are responsible for Socialist disappointment caused by the war. Cunow counsels a closer scrutiny of the actual course of development, and proceeds to a defense of Imperialism:

“The new Imperialistic phase of development is just as necessarily a result of the innermost conditions of the financial existence of the capitalist class, is just as necessary a transitional stage to Socialism, as the previous stages of development, for example, the building up of large scale industry. The demand, ‘we must not allow Imperialism to rule, we must uproot it,’ is just as foolish as if we had said at the beginning of machine industry: ‘no machine must be tolerated, let us destroy them, and let us henceforth only allow hand-work.’”

The spirit of Cunow’s attitude expresses a dangerous tendency latent in Socialist thought. It is what may be called the “historical imagination,” the tendency to view contemporary phenomena as one views the phenomena of history. This necessarily leads to reactionary concepts and paralysis of action. If there is error in the judgment of history, how much more error must there not be in judging history in the making? Even in history there are few developments which can be considered inevitable, except the broad general tendencies of social evolution. One may speak of the “inevitable this” and the “inevitable that” after the event, but it is dangerous to do so before the event. And particularly if we possess an insight into the processes of history: for of what practical value is this insight if it is not used in an attempt, at the very least, to direct the course of history?

Cunow sees in Imperialism a “necessary transitional stage to Socialism.” The German Socialists seem to possess a perfect genius for discovering “transitional stages” to Socialism in any and all things except Socialist activity itself. A generation ago, the conquest of political democracy was considered “a necessary transitional stage to Socialism,” and ended in making the Social Democracy a party of bourgeois democracy and social reform. Now the German party seems to have forgotten this “transitional stage,” and seems allying itself with a very opposite tendency, Imperialism, which is the arch-enemy of democracy. Is not the conclusion sound that this new “transitional stage” will prove as illusory as the preceding one? Cunow’s attitude amounts to a suggestion that the Social Democracy repeat the error which more than any other single factor resulted in its inglorious downfall.

The essential economic characteristic of Imperialism is the export of capital-investments. The circumstance that there are nations weak economically and politically develops the essential political characteristic of Imperialism–“spheres of interest” and ultimate conquest. But there is no inevitable connection between the two. The export of capital may take place without ultimate conquest. Should Mexico be conquered by the United States, the Socialist Imperialist would contend that it was an inevitable consequence of Imperialism; but allow Mexico a decade to strengthen its government and organize itself socially and industrially, and the excuse of the Imperialist for conquest–disturbed conditions of political and economic life–would no longer exist and the idea of conquest vanish into thin air. The problem confronting the Socialist, accordingly, is simple: Shall we encourage the conquests of Imperialism, or shall we use our power to compel Imperialism to hold itself in restraint, and encourage the peaceable national development of Capitalism in countries now the prospective prey of the Imperialist? The Socialist Imperialist argues that Imperialism performs a useful function by economically developing pre-capitalist countries. But this function can be performed without Imperialistic conquest, a consummation to be striven for by the Socialist. Japan developed capitalistically without Imperialistic conquest: why should not the phenomenon be repeated in China and Mexico? The comparison of Imperialism with machine industry is not pertinent: there is an alternative to Imperialism, there was none to machine industry.

Assuming that Cunow’s analysis is correct at all points, his tactical conclusion, “we must not fight Imperialism,” would still remain untenable, suicidal. Should Socialists cease their opposition to the exploitation of labor because that exploitation is necessarily a result of Capitalism? Is Socialism to become the historian analyzing the development of Capitalism, instead of a dynamic and revolutionizing factor in that development? Is the Socialist

movement to renounce its revolutionary heritage for the flesh-pots of Imperialism? In fighting Imperialism the Socialist movement doubly fights Capitalism; in abandoning the fight against Imperialism it would simultaneously abandon the fight against Capitalism.

American Socialists have usually imported their ideas from Germany, their contributions to those ideas being of a caricature nature. It is not surprising, therefore, to find an American Socialist adopting Cunow’s ideas, but repeating them in a form that would probably astound and shock Cunow.

In the Milwaukee Leader, Ernest Untermann has published a series of articles expressing definitely Imperialistic ideas. He accepts Cunow’s thesis, and then proceeds to apply it. In the course of this application, Untermann uses the phrase, “Revolution by Reaction”; and this phrase, caricature as it is and because it is caricature, aptly characterizes the attitude of the Socialist Imperialist.

Untermann quotes a saying of Engels, “Our reactionaries are the greatest revolutionists,” and then says:

“Militarism and colonial imperialism today seem the worst enemies of Democracy and Socialism, yet no other power so rapidly and effectively enforces co-operative discipline, kills anarchist individualism, destroys petty business disorganization and undermines the whole capitalist system nationally and internationally so thoroughly as these arch enemies of the common good are doing.”

Those of us who thought Imperialism strengthened Capitalism had better recant. And cease our opposition to American Imperialism, for, according to Untermann:

“Our American Imperialists, like their European brethren, must work for the revolution, whether they like it or not.”

Imperialism is a blessing in disguise to the people it conquers:

“Now the alternative facing the American capitalists is: Either a constitutional government of Mexicans controlled by influences hostile to American capitalists, or annexation of Mexico. If they choose annexation, they will give to the Mexicans with one hand what they take with the other. For if Mexico is annexed, the Mexican people lose their national independence, but they gain admission to the American labor movement and to the American Socialist party.”

The Mexican revolution is an illusion, and “Mexican independence not among the things that history has provided for, at least not so long as Capitalism rules this world.”

“The Mexican revolutionists, especially the little landholders and the peons, have simply been the credulous pawns of foreign adventurers.”

Strange as it may seem, the hope of Mexico lies in Imperialism: it is a “perfervid illusion” to hope that “American intervention can and must be prevented:”

“The real revolutionists in Mexico have been in modern times the American and English capitalists. They were the instigators of the present revolution, they will be the real spirits back of future capitalist revolutions. Peace can come to Mexico only by an agreement between these foreign capitalists. Whatever may be the surface indications, whatever may be the illusions of Mexican patriots, there can be but one outcome to the struggle in Mexico: The control of the country’s fundamental wealth by international finance. The sooner this end is achieved, the more Mexican lives will be saved, the more rapidly will the Mexican people enter upon that stage of their development which will ultimately emancipate them from all capitalist finance and from all Capitalism.”

Untermann’s insinuation that it would be an advantage for the Mexican people to “gain admission to the American labor movement,” is a strong argument against Mexican annexation. It would intensify the racial prejudices which are the curse of the American union movement. If the If the American labor movement oppresses and discriminates against the alien in this country today, that discrimination and oppression would be a hundred-fold worse against the Mexicans should they enter the American labor movement as a conquered race.

It is difficult to characterize the arguments of Untermann. The role they ascribe to the Socialist movement is that of Lazarus feasting on the crumbs of the Imperialistic Dives. They are a complete abandonment of Socialism. The Untermann attitude leaves the Socialist movement without any definite revolutionary function to perform, and strengthens Imperialism by imputing to it the fatality of the inevitable. Support American Imperialism in Mexico and you must support it against the Imperialism of other nations: and the vision evoked is of Imperialism fighting Imperialism, with Socialism supplying the justification of historical necessity and the enthusiasm of the fatalist.

The Socialist bases his conception of the movement upon the development of the working class, as determined by the development of Capitalism, while the Socialist Imperialist bases it upon the development of Capitalism. But Capitalism in itself is capable of an infinite development: the old theory of the inevitable collapse of Capitalism is untenable. There is no hope of revolution except in the development of the revolutionary proletariat.

The issue is this: Shall the Socialist movement organize dynamically for the overthrow of Capitalism, or shall it organize for the perpetuation of Capitalism?

New Review was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. In the world of the Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Maurice Blumlein, Anton Pannekoek, Elsie Clews Parsons, and Isaac Hourwich as editors and contributors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 on, leading the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable archive of pre-war US Marxist and Socialist discussion.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1915/v3n15-oct-01-1915.pdf