What a moment in the history of our class to have participated in.

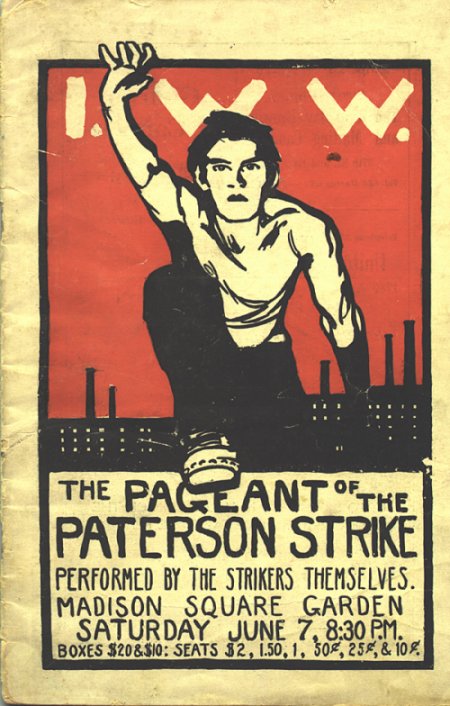

‘The Paterson Mass Play’ by Onlooker from Solidarity. Vol. 4 No. 23. June 14, 1913.

“The Pageant of the Paterson Strike” is now a part of the history great struggle between Capital and Labor that has raged for the past four months in the silk industry of this country. A mass play born of mass actors it was, like the old morality play, a play with a purpose, that marks the beginning of a new epoch in play writing and play acting. It had no plot, no heroes and heroines; yet it was as real, as significant, as interesting, as life itself, because it was a transient from the page of life itself. It was tremendously successful in the suggestion of the immense power and possibilities of solidarity that it conveyed to the audience of 15,000 persons assembled to see and hear it. Whatever may be its shortcomings from the standpoint of dramatic technique, as at present conceived–and there were many–the pageant possessed social significance as the democratic beginning of the stage as a medium for the presentation and solution of the social problem by those most directly concerned–the workers themselves.

The pageant was in six episodes. To properly present these, six different pieces of scenery were necessary; but their cost, owing to the immense size of the stage, was prohibitive; so only one scene was shown throughout–that of a giant mill. Of course, this lack of scenery prevented the illusion from being perfect, for the mill scene was also the burial scene, for instance, of Constantino Modestino. But despite it all, the imagination of the audience was fired, and the vast amphitheater often resounded with thunderous applause, or it was subdued with the silent intensity of the funeral scene, as the occasion required. In fact, it may be said, and this is worth noting also, that the audience was frequently as much a part of the pageant as the strikers themselves and appropriately so, for they were deeply sympathetic with the pageant, and responsive to its ultimate purpose, the abolition of wage slavery.

The pageant opened with the mills silent and dead. Soon the whistle blows, lights appear at every window, the workers straggle in listlessly, in pairs and groups.

Some stop to discuss the situation. The whirr of looms is heard and everything is in full operation. Then the strike begins. The mills pour out their thousands of workers, and are thereon prostrated–the situation is reversed; where formerly the mills were alive and the workers dead, the workers are now alive and the mills dead. Labor has ceased to slave for capitalist class. Its power to produce wealth is now used–passively–in its own interests. The general strike, the great weapon of labor, is now on!

When the 1,000 strikers, men, women, and children, of all creeds, colors, and nationalities, poured out of the mills, filling the stage and rushing down the entire length of the center aisle of the long amphitheater, shouting, “Strike! Strike!!” while, at the same time, the mills ceased their activity and were deserted and darkened, the impression was one of the onrush of a stupendous force, that, once properly harnessed, is irresistible and overwhelming. The picture was not only realistic and dramatic in the extreme, but also highly suggestive of Labor’s latent power. It seized the imagination with a grip that was expressed, after a short pause, in which its significance was grasped, in an outburst of cheers and applause that was prolonged and deafening. It was most impressive!

The next scene represented the picket line, and the struggles of the strikers against the unlawful and oppressive attempts of the police to destroy it. In this scene the impotency of the police and the repressive institutions and laws of capitalism in the face of mass action was revealed in a real and dramatic manner that once more aroused the big audience to a high pitch.

Then came the funeral of Constantino Modestino. Herein the workers pay tribute to the dead, placing carnations the flower emblematic of the workers’ colors on his grave, while pledging themselves to the care of his wife and children. This scene illustrated the wonderful self-restraint of the workers under strong feelings of resentment. It illustrated their class-love and their sense of class-loyalty. It was enacted with a repressed intensity on the part of both players and audience, who tolerated no applause during the grave speeches of Tresca and Haywood. It ended as it began, in somber mournfulness.

In succession came the Haledon mass meetings, with their enthusiasm and revolutionary songs; May Day and the sending away of the children, with their internationalism, filial and class affection; then the strike meetings in Turn Hall, with their working class legislation, by, for, and of the workers, on the eight-hour day. All these scenes were replete with suggestion, interest, and dramatic realism.

“The Pageant of the Paterson Strike” was an inspiration. It was a difficult proposition to stage. Time was short; the cast unwieldy; rehearsals were few; the idea was new; the attempt to transplant real life into an artificial environment was fraught with disaster. So that, all things considered, the pageant was a success. While interest dragged between the episodes, and appropriate scenery was lacking throughout, the pageant was a beginning in the right direction and fraught with great future possibilities.

ONLOOKER.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1913/v04n23-w179-jun-14-1913-solidarity.pdf