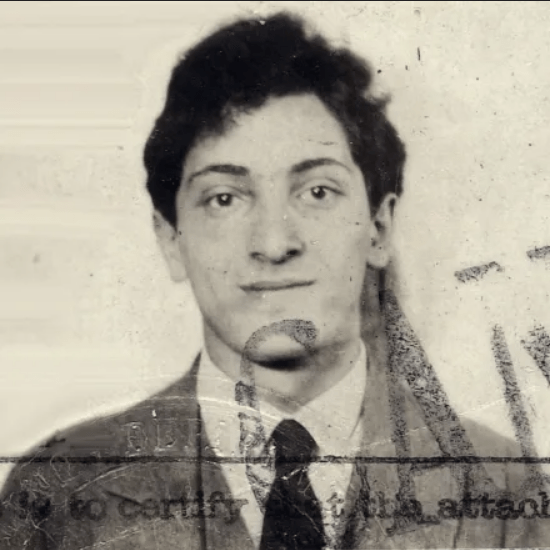

Designing buildings for human beings in a system designed for profits is an insoluble contradiction. Meyer Schapiro, who would become among the foremost art historians and critics of the 20th century, looks at the role and condition of the profession as shaped by the Great Depression.

‘Architecture and the Architect’ by Meyer Schapiro from New Masses. Vol. 19 No. 2. April 7, 1936.

THE architectural profession was almost completely ruined by the crisis. Residential building sank to one-tenth or normal. Unemployment was so wide- spread that the small percentage of architects and draftsmen at work in 1932 enjoyed only a seasonal and insecure occupation at a wage often less than half of their weekly incomes in 1929.

This slump was all the more catastrophic because of the extreme optimism of architects and their illusions of unlimited prosperity. For several years they had been employed on projects of magnificent scale, and had seen higher and higher buildings rising in the cities. Everywhere new building was evident; the prosperity of the middle and upper classes was realized in an immense quantity of private suburban homes. The sudden cessation of work was a shattering and unexpected blow.

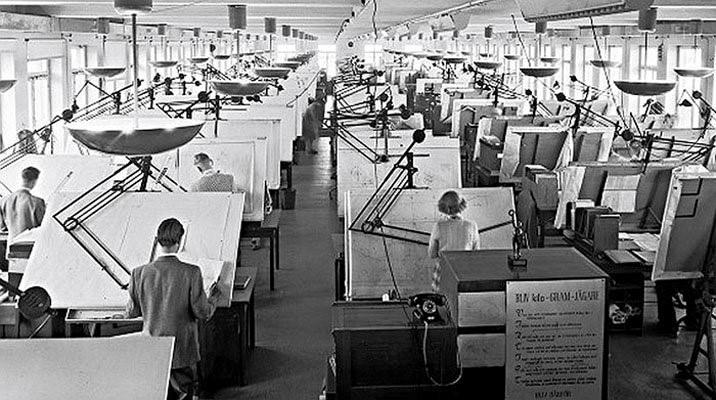

Already before 1929, the profession was acquiring a new character. Formerly made up largely of independent architects working on a percentage or fee basis, in their own small offices, employing a few assistants or draftsmen, the profession changed its composition more and more in the decade preceding the crisis. The salaried architects and draftsmen became the preponderant elements. As many as three hundred men were employed in the larger architectural offices. Large corporations, especially chain- stores, which required constant building or remodeling, employed their own salaried architects. In the great architectural offices the employers rarely engaged in the work of design, but were essentially business men who obtained contracts, supervised the activity of the office and affixed their signatures to the designs. These designs were commodities, protected by lawsuit against unfavorable architectural criticism. The employed architects and draftsmen worked anonymously and collectively; and although trained as artists who regarded their work as an individual expression, very few of them could realize a project completely or carry out a design in all its detail. The intense division of labor imposed by the scale, uses and techniques of modern building involved a routine specialization. The architect was forced to submit to commercial requirements often pernicious to artistic quality. At the same time, with the growing scale of operation, manufactured units were increasingly standardized. Less and less planning and drawing were required in suburban projects, made up of rows of almost identical houses, and in high buildings with repeated storeys of fairly uniform design, lacking ornament and mouldings. For a given floor space in 1929 perhaps half as much drafting was necessary as in 1920. Even if building had continued after 1929 at the same rate as before, technological unemployment seemed to be imminent in architecture.

The rationalizing of design was developed further during the crisis despite, or even because of, the cessation of building. Economists looked to the revival of the building industries for the first impetus in overcoming the depression. But no market existed, and an intense effort was made to discover means of reducing the cost of building, of designing standardized houses which could be produced largely in the factory and set up quickly with little labor and planning. It was hoped that such houses, sold at $1,500 to $3,500, would reach a market hitherto untouched by housing promotion, and play a role in American economy like the automobile during the last boom period. The numerous designs that emerged at this time could find no financial backing; such projects threatened the values of existing mortgaged property and past investments; and besides, the market was illusory. Savings had been consumed during unemployment, and the uncertainties of the slight upswing were unfavorable to such speculation. But even unrealized, these projects indicated the reduced prospects of the architectural profession. The new standardized types of housing required few designers.

Architects became aware now, if only from the literature of the construction industries, that the future of their profession lay largely in housing. But private capital cannot by itself build such housing. Wages are too low to permit a rent sufficient for profitable large-scale building operations. A government subsidy is therefore absolutely necessary for private building enterprise. The state is thus drawn into the field of housing, and the future of the architect, his economic security, the character of his work, are intimately bound up with the government’s policy. But even with such subsidy, private residential building must be decidedly limited, especially in the larger cities where land is so costly.

Architects, even of conservative tendency, recognize the present impasse of building. They observe a monstrous situation-immense technical resources for building, miserably housed masses, an army of skilled architects, technicians and building workers, unemployed or assigned to temporary relief projects.

Appeals from social workers, liberals and manufacturers for government support of private housing seemed to promise a renewal of building; but to date this promise has yielded very little. The government has poured out huge sums to salvage bad mortgages and has engaged in elaborate engineering projects, but the amount of subsidized or directly supported building of homes for the workers and lower middle class has been insignificant in proportion to the constantly proclaimed need and to the normal quantity of construction before 1929. At the same time the government has collaborated with private industry to reduce the wages of building workers and architects. The pay of skilled architects assigned to federal and local projects has been fixed at $23 to $30 a week-half, and in many cases, one-third of their wage before the depression. And even the present low standards have been won only through the militancy of the first national union of architects, the Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists and Technicians.

During the crisis, architects have lost their zest for esthetic problems. Architecture is an art only when people build; the alternatives of design must be real to excite enthusiasm and conflict.

Modern architects are stimulated by the wonderful variety of materials and the new technical resources of building. They are inspired by the thought that they are at the same time imaginative artists and scientific technicians, that they create communal environments as well as spectacles for the eye, and that their creations touch upon every aspect of human life. But these possibilities are hardly realized today; and the writings of architects, who appreciate the dignity of their art, have an inevitable utopian ring. The most progressive and gifted European architects have to their credit many plans, but few buildings; and those who were most active in Germany before 1933 are now in exile. Although large-scale planning is, for economic reasons, essential to architecture as a technique and as an art, such planning under capitalism cannot attain the freedom, the control over its means and ends, which existed for older architects in designing single buildings. There are few if any projects assigned to architects in which they can build according to the most advanced scientific and human standards. If they design housing on a large scale, they plan for low standards of living, tiny rooms and mediocre equipment; if they build skyscrapers, they build to advertise a property, and design structures which are forcedly vulgar, pretentious and unhealthy, and which add to the miseries of city life. The good modern buildings are few in number, rare, almost exotic structures, more often those in which no conscious reference has been made to artistic values or human needs, but have respected the highest requirements in the proper housing and operation of machines.

In the human housing projects, all phantasy and expression are excluded beyond the incidental by-products of the commercially calculated results and those inexpensive feeble adjustments of minor surface details which announce an artistic ingredient. This poverty of form is sometimes blessed as an admirable simplicity, suited to the age, and is compared with the qualities of a villa by Le Corbusier. But whereas this bareness of surface in a large private dwelling planned by Le Corbusier for a rentier esthetic is an elegant, highly-formalized and studied solution, enhanced by choice materials, ample spaces, fine furniture and pictures, and by the complexities of freely designed interior vistas, in the poorer homes, with its small rooms, low ceilings and plain walls, it is simply the expression of the celebrated “minimum standards” with which functionalist architects have been so preoccupied.

This situation is not inherent in the nature of architecture or modern technique. It follows rather from economic and social factors. The efficiency, continuity and progress of building depend today on two essential conditions-centralized large-scale planning, and a high and steadily rising living standard of the masses. State capitalism, fascist control, might realize, to a certain degree, the first condition; but only for a short period and at the expense of the living standards of the masses. It could design barracks and battleships, and monumental public buildings to serve the rulers’ vanity, but it could not provide superior homes and cities for the entire masses. Only a socialist state could guarantee the latter.

When both conditions are present, the modern architect will really come into his own. A planned city cannot be designed mechanically or by mere repetition of a unit but requires the collective work of hundreds of architects; and the dwellings and schools of a classless society, with the highest standards available to everyone, become problems of art and technique calling for the imagination and unhampered intelligence which have. presided in the best architecture of the past about these conditions. The change rests finally on the strength of the revolutionary working class.

In supporting the workers, to whom he is allied as a producer and as an exploited and insecure professional, the architect acts for his own interest and the interests of his craft function.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1936/v19n02-apr-07-1936-NM.pdf