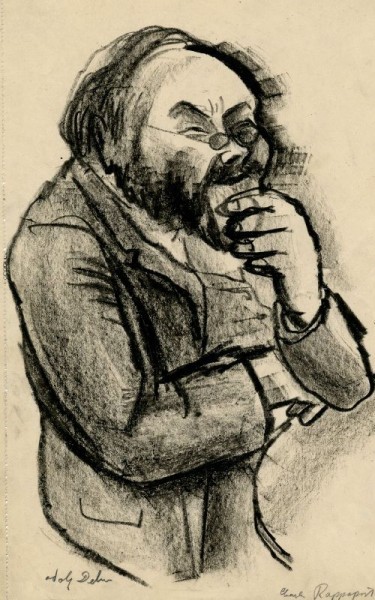

A brilliant essay from Charles Rappoport who was ‘present at all International Congresses, without exception since the second International was founded at Paris in 1889’ and attended 1919’s vain attempt by the International’s former grandees to revive the dead organization in Berne.

‘The Logic of Insanity’ by Charles Rappoport from Class Struggle. Vol. 3 No. 2. May, 1919.

I have just returned from Berne, where I have watched, with mingled feelings, the vain attempts of our International Opportunists to galvanize the corpse of the second “nationalist” International and to restore to it the spirit that brought about the socialist catastrophe of August 4, 1914. I should, I suppose, give a record of the impressions I received there, but events of such far-reaching significance, of so much vaster scope are attracting our immediate attention.

The insane madmen who loosed this tempest upon the earth, still continue to rule the world, leading it recklessly onward, along the path that leads to an abyss and bloody chaos. Twenty million men, the flower of the world’s vigorous youth, have been sacrificed in vain. Forty billion dollars in property have been uselessly destroyed, for the general education of our honorable rulers. The misery that awaits thousands of households, the dreadful epidemics that continue to be a constant menace to every one of us, the terrific rise in the cost of living, all of these questions so vital to the peoples of all nations, are of no significance to our blind and war-mad nationalists. They shout for annexations of territory and peoples, they demand mines and natural resources for capitalist exploitation. They have no thought of the future. Like primitive savages they live only for the present. After us the Deluge!…A deluge of blood and tears.

And yet this nationalist insanity too, has its logic, a logic that is irrefutable so long as one considers it from the premises furnished by these four years of horrible slaughter. For, after all is said and done, Germany and her allies did attack innocent and unarmed peoples. And, in the logic of war and the capitalist class, the defeated violator of defenseless nations must be made to atone for his wrong-doings. Shall the victims pay the price of Germany’s wrong-doing? Shall not the incendiary pay for the damage the fire has wrought? And since the havoc exceeds even the wildest flights of imagination, shall not the price of his atonement be equally bitter?

It is natural that the “majority” socialists, having made the historical philosophy of the capitalist class their own during the war, should be somewhat embarrassed now that the time has come when they must draw the practical conclusions of their process of reasoning during the war. The guilty must pay, and the guilty are to be found only on one side…

It is by no means a new problem that the world is being called upon to face. Bismarck and his band, in 1870, reasoned not a whit differently. According to the author of the Ems despatch France alone bore the responsibility of the war, was the aggressor. And though, after the battle of Sedan, the French envoy, General de Wimpfen, showed the implacable victor that it would be a political blunder to continue to aggravate the French nationalist sentiment, although Bismarck was warned of the frightful consequence for the future, the iron soldier, drunk with the wine of victory, answered with the irrefutable logic of madness, “No war indemnity, no matter how huge the sum may be, can compensate us for our enormous sacrifices. We must protect Germany on the South, the most vulnerable point exposed to French attack. We must put an end forever to the pressure that France has exercised, for two centuries in the past, upon German peoples, at the expense of the whole German nation…Baden, Wuerttemberg and the other southern states must no longer live in fear and terror of Strassburg.”

In place of “the southern states” place the phrase “Paris is too near the border” and you will find that we have adopted the same process of reasoning, in favor of the opposite side. But with far greater consequences.

“During the last one hundred and fifty years,” reasoned the blood and iron Chancellor, “France has waged more than a dozen wars against south-western Germany. The attempt has been made to acquire certain guarantees against such attacks, but whatever these states obtained was a snare and a delusion…The real danger lies in the incurable arrogance, in the tireless ambition of the French character (just as to-day our annexationists speak of the “German character”). We must protect ourselves against this peril, not by attempting to placate French susceptibilities, but by insuring ourselves of an adequate borderline. France, in its ceaseless attacks upon our western border, has again and again penetrated southern Germany with relatively small forces, before help could possibly be sent from the North. These invasions have been repeated, time and again, under Louis XIV., under the Republic and the first Empire, and the German states have constantly been forced to pit their strength against that of France.”

Bismarck knew that the “annexation of a slice of territory would be bitterly resented by the French.” But the Great Statesman, intoxicated by victory, formally declared this consideration to be of “little importance”.

Not that Bismarck failed to foresee the campaign for revenge. But he stilled his anxiety with logic, and this same insane logic, in all its dangerous plausibility, is being echoed and re-echoed to-day by our block-headed press. “An enemy who can never be made into a friend must be fought to the bitter finish. Only the complete surrender of the eastern fortresses of France can guarantee our safety.”

One almost feels that Bismarck must have been a constant reader of to-day’s le Matin. And since the strangling of a vanquished nation must always be accomplished in the light of pacifism and idealism, the reasoning beast of prey adds: “Everyone who is desirous of international disarmament must desire that the neighbors of France act in this light, for France alone endangers the peace of Europe.” (See les Memoirs, by Maurice Busch, of 1898.)

History repeats itself, atrociously and stupidly. However, there are some variations. In face of the unlimited demands of the Prussian super-militarists, who, together with Count Waldersee, the same, we believe who in 1900 commanded the Allied troops as well as the French in the Chinese Expedition, demanded the eternal destruction of the “Paris Babel.” The Statesman, more clearsighted, after all, than the pride-maddened Junkers, here showed stiff resistance and somewhat reduced the “bill” that France was condemned to pay.

Have we a Bismarck? It seems doubtful. But there is no doubt that the military caste everywhere reasons in the same way, is madly charging down the same incline of victory.

And there is yet another difference. A few days ago our friend, Jean Longuet, brilliantly introduced, at I’Ecole Socialist, his very interesting book on the “Politique exterieure du Marxisme.” He pictured the heroic resistance of the first International to the annexationist appetites of a victorious Germany. The Berne conference did not even consider the possibility of such opposition, except perhaps in a few generalities that had neither force nor color.

Where are our Bebels and our Liebknechts?

They are dead, assassinated. And the living failed to speak there where their words might have had real historical significance. And so the blind are leading the lame toward the final cataclysm, in an atmosphere overcharged with electricity.

Poor France! Poor Humanity!

Headed for Stockholm (via Russia), we arrived at Berne. The allied governments, in their wisdom, why, normal human intelligence fails to comprehend, have at last, after four years of war, condescended to allow us to cross the borders into a neutral state. French and German Socialists have shaken hands — and the world did not totter!

It has been my privilege to be present at all International Congresses, without exception since the second International was founded at Paris in 1889, on the occasion of the first centennial anniversary of the French Revolution. But never have I witnessed a Congress so dull, so poor in thought and so devoid of revolutionary or even of idealistic sentiment than this. A hundred delegates, flanked by at least 200 more or less authentic journalists, were gathered together there in a bare hall. There was no Socialist insignia, no bit of red cloth, not even the traditional bust of Karl Marx or the famous rallying cry “Workers of all countries, unite” without which there has never been an International Congress. Truly, it seemed more like a meeting of old veterans, or of agricultural comitias ….

But even more important was the complete absence of frank and fearless expression, the lack of a single popular breath. The few courageous minority members, and even ex-majority members felt themselves completely submerged by a marsh of stagnation, of auguries and sub-auguries, of hallway diplomats, of old and future ministers, and Socialist ministers actually in office.

After four years of the most terrific struggle that the world has ever seen, after four social revolutions (in Russia, Germany, Austria and Hungary, one had hoped for something better. But they did not dare to broach the most important subject, the question of the responsibility of the different Socialist sections for the assassination of the International. French ex-majority and German majority Socialists generously declared a general, amnesty and together formed a solid counter-revolutionary and anti-bolshevik bloc. The reconciliation was made at the expense of Lenin.

Instead of forcing the responsible capitalist regime to face the responsibility of its millions of dead, instead of charging the guilty with their foul murder, they prepared themselves to chastise the Bolshevik.

This struggle, at long distance, against a social revolution, in the midst of its revolutionary period, by a body whose very existence was based upon the principle of the overthrow of the capitalist system, was so comic that even the authors of that gloomy enterprise backed down before the ungrateful task.

All of the most important decisions were put off. It was, in truth a Congress of postponements. It would have been far wiser had the Congress adjourned until a more favorable time when the proletariat, which is now busy with other things, would have an opportunity to make its presence felt. Only once was there at least a semblance of international solidarity. It was the question of the German prisoners. But even here the French ex-majority Socialists found a way out of the difficulty by leaving the initiative, with generous impartiality, to the German minority member, Kurt Eisner, who, in the face of our social patriots, branded the military reactionaries of his own countries, as we were all wont to do in the good old days before the war. Renaudel did not fail to step on the tender corns of the others with the heavy clumsiness that characterizes this shrewd native of Normandy. But nobody whispered a word about our own prisoners, of those Socialists in all countries that are being held by their own bourgeois ruling classes.

Not one problem of Socialist politics, or, for that matter of world politics, found serious discussion. True, the Bolshevist problem was broached. But even here the discussion centered rather on the relations between Socialism and democracy. The subject, furthermore, was put on an absolutely unacceptable basis: dictatorship or democracy. As if every Socialist who knows the ABC of Socialist philosophy did not know that there is no such thing as bourgeois democracy under capitalism. For us the choice lies not between dictatorship and democracy but between capitalist dictatorship and Socialist dictatorship, between a dictatorship for and of the people, and a dictatorship against the people.

In France we have, at this moment, a dictatorship of the past We proclaim to the world that we will put in place of the dictatorship of the deputies of a dead age, the dictatorship of the oppressed masses.

The Class Struggle is considered the first pro-Bolshevik journal in the United States and began in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution. A bi-monthly often over 100 pages and published between May 1917 and November 1919, first in Boston and then in New York City by the Socialist Publication Society. Its original editors were Ludwig Lore, Louis B. Boudin, and Louis C. Fraina. The Class Struggle became the primary English-language paper of the Socialist Party’s left wing and emerging Communist movement and paid lose attention to the fight in the Socialist Party and debates within the international movement. Many Bolshevik writers and leaders first came to US militants attention through The Class Struggle, with many translated texts first appearing here. Its last issue was published by the Communist Labor Party of America.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/class-struggle/v3n2may1919.pdf