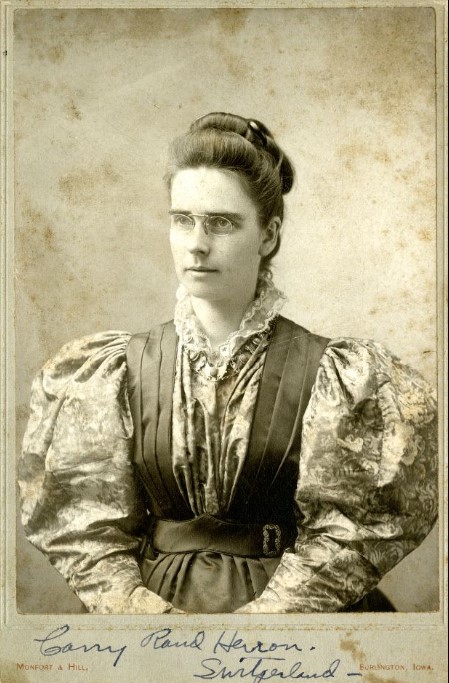

Clearly a passion, founding delegate to the Socialist Party and benefactor of the Rand School of Social Science introduces the life and work of Ludwig van Beethoven to the Comrades.

‘Ludwig von Beethoven’ by Carrie Rand Herron from The Comrade. Vol. 3 No. 4. January, 1904.

BONN, a town on the Rhine a few miles above Cologne, was the seat of an electorate and numbered some 10,000 inhabitants, which were chiefly people of the court, and the priests. It was here, December 16th, 1770, that Ludwig van Beethoven was born. He was the oldest son of Johann and Maria Magdalena Beethoven. The father, who sang tenor and received an appointment as court singer, inherited from his mother a desire for liquor, which doubtless caused Ludwig much, trouble and anxiety during his early life. His mother was the daughter of a head cook. The “van” in the name is not a title of nobility, as is usually supposed; and Beethoven once said, pointing to his head and heart, “my nobility is here and here.”

Ludwig’s musical education began when he was very young. His father began teaching him the rudiments of music when he was not yet four years old, and at this time he was obliged to practice hours on the pianoforte each day. Soon he also began practicing on the violin, and he would be locked in his room until the daily task was finished. It is said he did not at all like to practice on the latter instrument. He was soon put under the instruction of Tobias Pfeiffer, who was as fond of drink as Beethoven’s father, and they would spend hours together at the inn, when Pfeiffer would remember the boy had had no lesson that day. He would then go and drag the child from bed, and often keep him at the instrument until daybreak. As we see, the boy’s training was severe and exacting in the extreme. He had but little education aside from music. He learned to read, write and reckon, but before he was thirteen his father decided his scholastic education was finished. His lack of education was a sore trial and mortification to him all his life, though from a boy he was a great reader.

He was a sombre, melancholy person and seldom joined in the sports of his age.

At the age of eleven, he is said to have played the piano- forte with “energetic skill.” At about this time, he wrote nine variations on a given theme, which his teacher had engraved to encourage him. Neefe, with whom he was studying, and to whom Beethoven, after many years, acknowledged his many obligations, said that if he should keep on as he had begun that he would surely become a second Mozart.

At eleven years and a half old, he played the organ in the absence of the organist. The next year he assisted at operatic rehearsals and played the pianoforte at the performances. At about this time, he became almost the main support of his mother and brothers. When he was thirteen, the first three sonatas were published. A year after he was named second organist.

In 1787, when he was sixteen years old, he went to Vienna where he met Mozart and took a few lessons from him. After Beethoven had invented a fantasia on a given theme, Mozart said to those present, “Pay attention to this youngster; he will make a noise in the world one of these days.”

He was soon called back to Bonn by the death of his mother. After this, he had the care and responsibility of his father and two younger brothers. In 1792, the father died, and soon after Beethoven left Bonn and went to Vienna, which place he made his home until death. Being away from there only for a short time now and then, Beethoven, who is without doubt the greatest of all instrumental composers, began his career as a pianoforte virtuoso, and his earliest compositions are principally for that instrument. At this time he was chiefly known for his extempore playing. His compositions were as yet insignificant.

For three years after going to Vienna, he devoted himself to study, taking lessons from Haydn among others. With but few exceptions, he was unpopular with his teachers. They considered him obstinate and arrogant, and his “I say it is right” was anything but pleasant to them. Haydn prophesied greater things of him as a performer than a creator of music. His superiority as a performer even was not so much in display of technical proficiency as in the power and originality of improvisation as “most brilliant and striking; in whatever company he might chance to be, he knew how to produce such an effect upon every hearer, that frequently not an eye remained dry, and listeners would break out into loud sobs; for in addition to the beauty and originality of his ideas, and his spirited style of rendering them, there was something in his expression wonderfully impressive.” He was very particular as to the mode of holding the hands, and placing the fingers, in which he followed Bach; he had a great admiration for clean fingering; his attitude at the pianoforte was quiet and dignified. He did not like to play his own compositions, and only yielded to an expressed wish when they were unpublished. He was a superb pianoforte player, fully up to the requirements which his last sonatas make upon technical skill, as well as intellectual and emotional gifts.

Czerny, who was a pupil of Beethoven, describes his technique as tremendous, better than that of any virtuoso of his day. He was remarkably deft in connecting the full chords, in which he delighted, without the use of the pedal. But it was upon expression that he insisted most of all when he taught.

He was hot tempered and rude, and though he had friends, yet he often quarreled with them. The noble women of Vienna were fond of him and his rudeness seemed to fascinate them; even when he would roar angrily at a lesson or tear the music in pieces, they would not become offended. He never married, but was devoted to, and in love with, one woman after another.

Czerny was but ten years old when he met Beethoven, and some years after he wrote as follows: He mentions the apartment as a “desert of a room-bare walls-paper and clothes scattered about–scarcely a chair, except the rickety one before the pianoforte. Beethoven was dressed in a dark gray jacket and trousers of some long-haired material which reminded me of the descriptions of Robinson Crusoe. The jet black hair stood upright on his head. A beard, unshaven for several days, made still darker his naturally swarthy face; his hands were covered with hair, and the fingers were very broad, especially at the tips.”

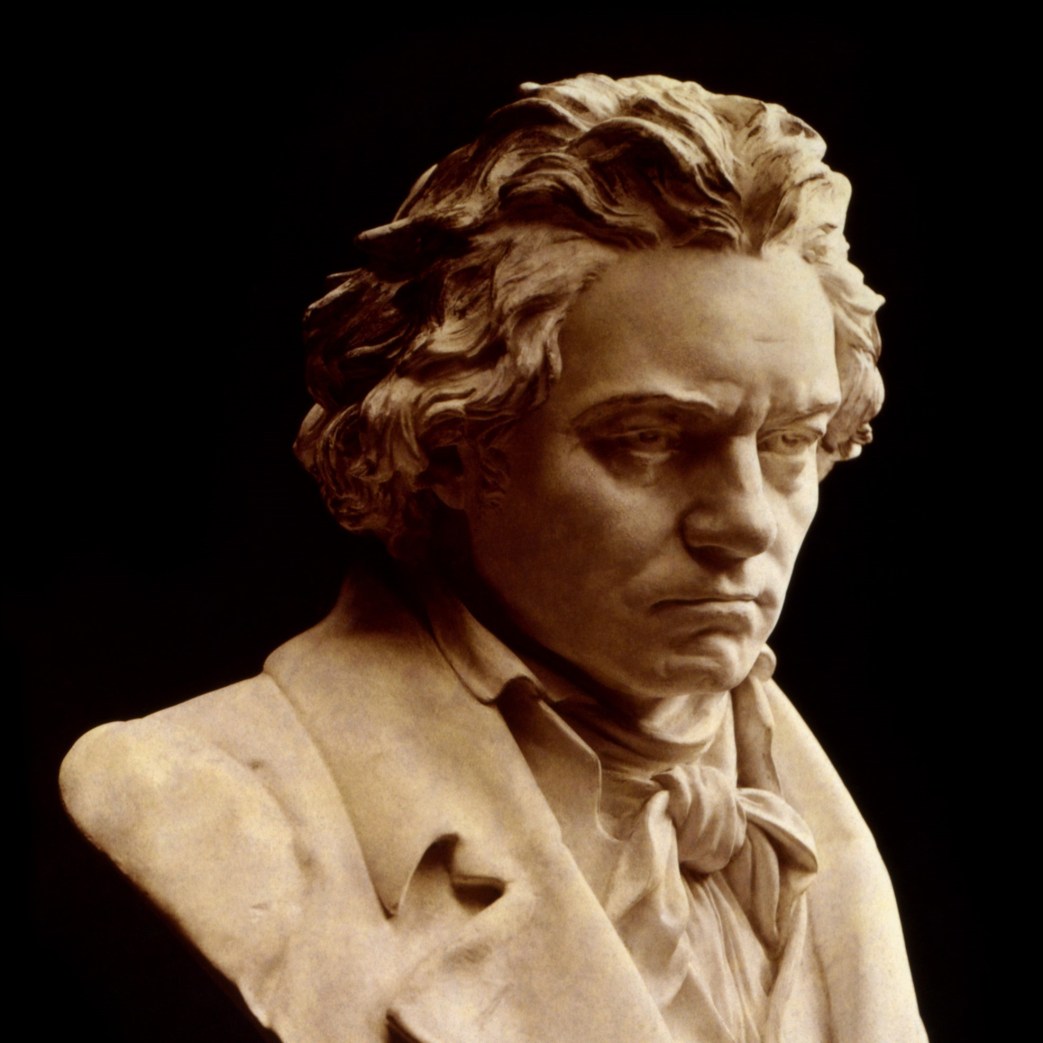

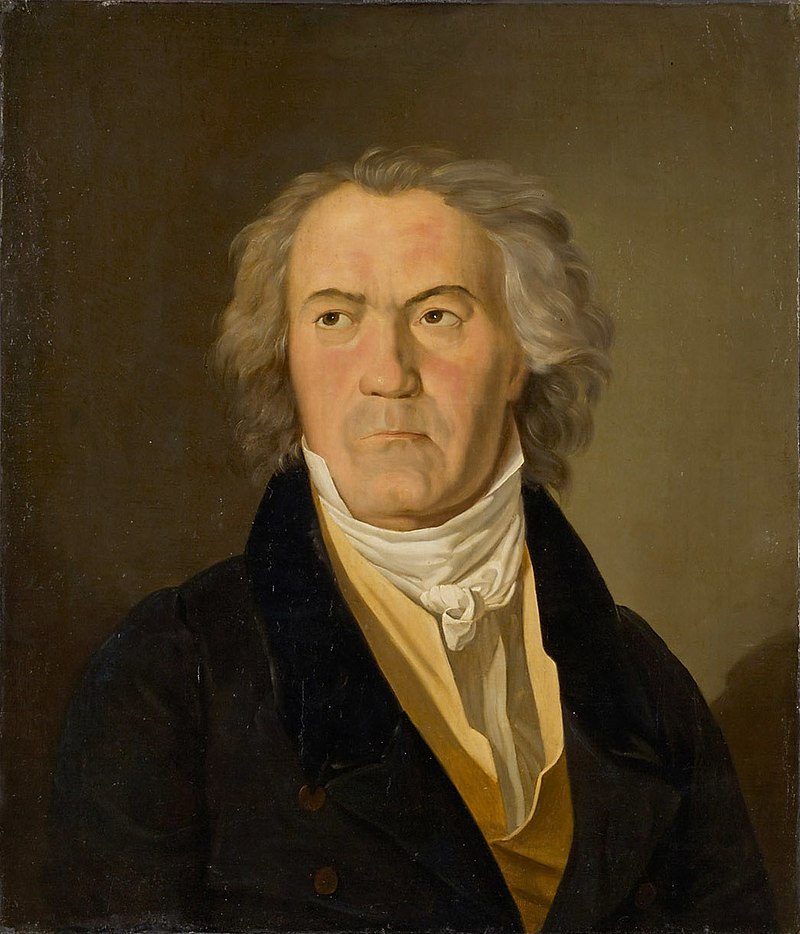

Beethoven was short, but broadly built, and awkward though quick in his movements. However careless he may have been in his dress at ordinary times, it is evident, from the society which he occasionally frequented, that he must have possessed the art of making himself presentable, and, leaving all questions of dress aside, the countenance contains many fine traits. Especially is this true of the mouth, which is singularly sweet and flexible. The eyes also are deep and serious, and the whole impression of the man must have been not alone that of force, physically considered; but still more so, as shown in his countenance, the expression of a deep and noble spiritual force. This quite agrees with what we read of the master’s incisiveness and directness in conversation, and his mirthfulness, with his loud and ringing laugh. He was simple in certain ways and easily tricked or deceived. He was also absent-minded. He enjoyed pranks at the expense of others. He was of a restless nature and changed his lodgings often. The influence of heredity, the early unfortunate surroundings, the physical infirmity that was probably due to the sins of his father, the natural impatience with the petty cares of life on the part of a man whose head was in the clouds: all these unfitted him for social intercourse with the gallant world in which he was, however, a welcome guest. He preferred nature to man, and was never so happy as when walking and composing in the open. In fields and woods, he meditated his great compositions. If ever there was an ardent lover of nature, it was the composer of the Pastoral Symphony. The twilight was his favorite hour for improvising.

His first appearance in Vienna in public was in 1795 at the Burgtheatre, at which time he played his pianoforte concerto in C major. There was a difference of half a tone be- tween the piano and the orchestral instruments, and he played the concerto in C sharp major.

When Beethoven was but twenty-six years old, he had a severe illness which eventually settled in the organs of hearing. Everything was done that could be, but total deafness was the final outcome.

“You cannot believe,” writes a friend, “what an indescribable impression the loss of hearing has made upon Beethoven; imagine the effect on his excitable temperament of feeling that he is unhappy; then comes reserve, mistrust often of his best friends, and general irresolution. Intercourse with him is a real exertion, as one can never throw off restraint.” “Beethoven’s deafness,” says Goethe, “has not hurt so much his musical as his social nature.”

It may be questioned if his musical nature were affected at all other than favorably by his infirmity. His art was greater than the man, or rather the man in his art was greater than himself; his deafness, even by shutting him within, seems to have increased his individuality, for, from the time of its absolute establishment onward, his compositions grew in musical and intellectual value, and each generation finds in them something new to study and to appreciate. He wrote not for his time alone, but for all time.

It was about the time his deafness came upon him that he composed almost constantly. Whether his deafness had anything to do with it, or whether it was owing to his natural development, I do not know. He said in a letter, “I live only in my music, and no sooner is one thing done than the next is begun; I often work at three or four things at once.”

Beethoven was a great admirer of Napoleon as long as he was First Consul, and named one of his symphonies “Bonaparte”; but when Napoleon made himself Emperor of the French, Beethoven burst into violent reproaches and tore in pieces the title page of his symphony.

He revered the leaders of the American Revolution, for he was a republican by sentiment. He dreamed of a future when all men should be brothers, and the finale of the Ninth Symphony is the musical expression of the dream and the wish. He was born in the Roman Catholic faith, but his prayer book was “Thoughts on the Works of God in Nature,” by Sturm. Many passages in his letters show his sense of religious duty, and his trust and humility.

He copied and kept constantly on his work table these lines found on an Egyptian temple:

I am that which is.

I am all that is, that has been, and that shall be;

no mortal hand has lifted my veil. He is by himself,

and it is to him that everything owes existence.

In 1815 his brother Caspar died, leaving the care of his son Carl to the uncle. The boy caused Beethoven much anxiety and trouble, and proved to be of little worth. And the last years of Beethoven’s life were filled with sorrow on account of the boy. He would make any sacrifice for his nephew and offered his manuscripts to the publishers in order to procure money for him.

In December, 1826, Beethoven caught a severe cold from exposure which resulted in his death, March 26th, 1827. In his last illness, he was in real need of help. He at last sent to two former friends, members of the Philharmonic Society, begging them to arrange for a concert of his benefit. The Society immediately sent him five hundred dollars. Most of his friends had forgotten him, or were too busy to do anything for him at the time of his great suffering and need.

No musician has rivaled Beethoven. His works are much more than the works of other masters, of a nature peculiar to themselves. This peculiarity manifests itself in the fact that through his works, instrumental, and more particularly pianoforte music, attained to idealism and became the expression of determined ideal thought. Before this time, they had been (with a few exceptions of Bach) only a graceful play of tone figures, or else a re-echoing of flitting and indefinite frames of mind. But even such of Beethoven’s works in which no ideal content can be traced, distinguish themselves from the large majority of all others (except Bach) through the earnestness and endurance with which the master has developed them.

The individually different character of Beethoven’s pianoforte works explains the reason why the works of other masters do not serve as a preparation toward the study of these. We may know the compositions of all other composers, and yet find ourselves in a new world with Beethoven. And with him, one work does not even sufficiently prepare for the understanding of another. With many composers to conquer one is to be able to master all, but with Beethoven, it is not so. Each work makes its own particular demands; therefore each must be individually conceived.

Through Beethoven we are lifted up into the ideal kingdom of art, and we gain through each work a new and peculiar perception. To interpret a work of this master, not only a certain degree of proficiency in technique is required, but also thought; and it is this last that so many are unable or unwilling to give.

Beethoven began with the sentiment and worked from it outwardly, modifying the form when it became necessary to do so, in order to obtain complete and perfect utterance. He made spirit rise superior to matter.

More than anyone else, it was Beethoven who brought music back to the purpose which it had in its first rude state, when it sprang unvolitionally from the heart and lips of primitive man. It became again a vehicle for the feelings. As such it was accepted by the romantic composers to whom he belonged as father, seer, and prophet, quite as intimately as he belongs to the classicists by reason of his adherence to form as an essential in music. To his contemporaries he appears as an image-breaker, but to the clearer vision of to-day he stands an unshakable barrier to lawless iconoclasm.

He was not a mere professional radical, altering for the mere pleasure of altering, or in the mere search for originality. He began naturally with the forms which were in use in his days, and his alteration of them grew gradually with the necessities of his expression. The form of the sonata is “the transparent veil through which Beethoven seems to have looked at all music.” And the good points of that form he retained to the last; but he permitted himself a much greater liberty than his predecessors had done in the relationship of the keys of the different movements, and in the proportion of the clauses and sections with which he built them up. In other words, he was less bound by the forms and musical rules, and more swayed by the thought which he had to express and the directness which that thought took in his mind. “A trace of heroic freedom pervades all of his creations,” says Ferdinand Hiller.

Everything conspired in Beethoven to make his utterance authentic, strong, unqualified-like a gushing spring which leaps from inaccessible depths of the mountain. His solitary habits kept his mind clear from “the mud and sediment which the market-place and the forum mistake for thought;” his deafness coming on at so early an age (twenty-eight) increased this effect, it left him fancy-free in the world of music.

One may mention, as an indication of the great range and strength of his personality, its exceeding slow growth. While Mozart at the age of twenty-three had written a great number of Operas, Symphonies, Cantatas and Masses, Beethoven at the same age had little or nothing to show. His first Symphony and his Septet, which he always looked back upon as childish productions, were not written till about the age of twenty-seven; and his first great Symphony not till he was thirty-two.

Up to Beethoven, the history of music-pure music- shows a slow steady growth and development of musical form along two or three simple lines. It is Edward Carpenter who most beautifully and finally sums up the music and life of Beethoven:

“It is like the long slow slope which leads on one side to the summit of a mountain. Hither in the bold sunrise we ascend, and such names as Corelli, Scarlatti, the two Bachs, Händel, Haydn, Glück, Mozart are the great landmarks of the way. The route is clear. The lines of tradition in minuet or gavotte, in fugue-form or sonata-form, shift slowly and continuously around us. With Beethoven, the pinnacle is gained; an immense outlook widens on all sides; there is an impression of boundless space; a vision of other lands, dim, distant, full of wild surmise.

“But thenceforth we descend. We have come to the other and more precipitous slope. The mountain breaks away in wild crags and wooded gorges. The calm classical outlines rule no more; they are replaced by forms of fantastic and wonderful beauty, but forms of decadence. Schubert is there at the entrance of that religion, with his exuberant gift of divine melody; Schuman with his intensely literary, modern, pathetic, striving, self-conscious spirit, always a little uncertain and unbalanced; Mendelssohn and Chopin too, leaning over the gulf of the sentimental–the one in an optimistic, the other in the opposite direction; and Brahms, who shows again the grand outline of his predecessor’s work, but with an intellectual rather than a prophetic effect, and many others.

“Then the whole slope breaks away, Pure Music–founded on the base of the old Tonality, and built up over a stretch of three centuries on the great structural lines which flow from the principle of the keynote-has now fulfilled its work and comes to an end, giving place to Programme and Opera: Music, in fact, returns in latest times to the source from which it originally sprung: to be the handmaid of the voice and of speech, and the auxiliary to Life and dramatic action instead of an independent Art, bearing witness to its own message in proud isolation.

“Beethoven came at the culmination of a long line of musical tradition. He came also at a moment when the foundations of society were breaking away for the preparation of something new. His great strength lay in the fact that he united the old and the new. He was epic and dramatic, and held firmly to the accepted outlines and broad evolution of his art, like the musicians who went before him; he was lyrical, like those who followed, and uttered to the full his own vast individuality. And so he transformed rather than shattered the traditions into which he was born.

“Beethoven was always trying to express himself, yet not, be it said, so much any little phase of himself or of his feelings, as the total of his life-experience. He was always trying to reach down and get the fullest, deepest utterance of which his subject in hand was capable, and to relate it to the rest of his experience. But being such as he was, and a master-spirit of his age, when he reached into himself for his own expression, he reached to the expression also of others to the expression of all the thoughts and feelings of that wonderful revolutionary time, seething with the legacy of the past and germinal with the hopes and aspirations of the future. Music came to him, rich already with gathered voices; but he enlarged its language beyond all precedent for the needs of a new humanity.”

The Comrade began in 1901 with the launch of the Socialist Party, and was published monthly until 1905 in New York City and edited by John Spargo, Otto Wegener, and Algernon Lee amongst others. Along with Socialist politics, it featured radical art and literature. The Comrade was known for publishing Utopian Socialist literature and included a serialization of ‘News from Nowhere’ by William Morris along work from with Heinrich Heine, Thomas Nast, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, Edward Markham, Jack London, Maxim Gorky, Clarence Darrow, Upton Sinclair, Eugene Debs, and Mother Jones. It would be absorbed into the International Socialist Review in 1905.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/comrade/v03n04-jan-1904-The-Comrade.pdf