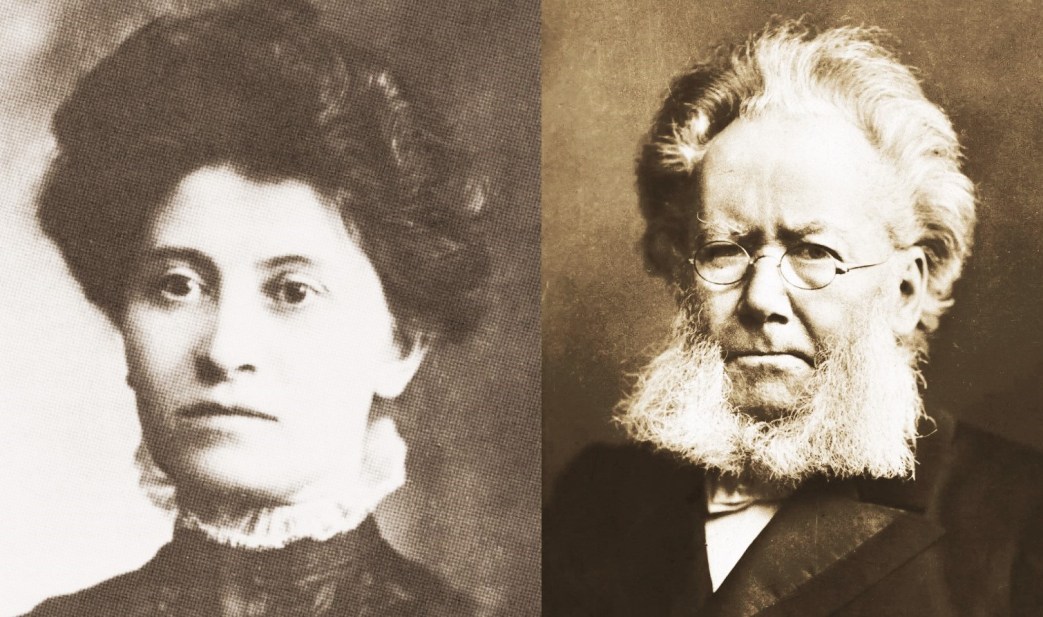

‘Ibsen’s ‘Ghosts’’ by Theresa S. Malkiel from Progressive Woman. Vol. 4 No. 39. August, 1910.

Of all the numerous dramas written by Ibsen, “Ghosts” is the one that should be read by every intelligent man and woman. In no other play does Ibsen give us such a direct and clear picture of the dark, hidden skeletons existing in our modern family life.

His great master mind did not only comprehend the terrible corruption and degeneration. that is steadily undermining our society, but, looking back into the bygone years, he recognized amidst the thick vapors of the surrounding atmosphere the ghosts of those who have passed away before us.

In the life tragedy of Mrs. Alving he tells us ably how she was pursued by the ghost of her dead husband, pointing out to us that the harm the latter had wrought to his wife was not eradicated by his death. In reading this drama we can’t help realizing the truth of the assertion that the sins of the fathers are visited upon the children.

In this like in many other of his works Ibsen draws for us the picture of one single woman, but if we read the contents carefully we are bound to recognize the fact that the suffering, hidden humiliation and sorrow experienced by Mrs. Alving are the lot of thousands of other women.

Mrs. Alving while a young, beautiful and innocent girl is married to a man much older than herself-a man who had tasted all that was exciting and forbidden in decent society. The unfortunate wife realized from the first month of their married life that she had made a grave mistake in marrying him–she found out that her husband was too much given over to his former pleasures to curtail them for the sake of the young bride. The awakening was terrible and after a year of torture and humiliation the woman fled, only to come back to him at the insistence of her priest.

Upon her return she bore and suffered in silence for almost two decades. Ten years after his death, when she was about to dedicate an orphanage to his memory and thus silence her own conscience, while the same priest was invited to bless the institution she cared to make a confession to him concerning the misery of her wedded life, and this not without a provocation from the priest. It is the gist of that conversation which will give the reader an idea of the whole situation.

Upon discussing the orphanage the priest said to Mrs. Alving: “Yes, Mrs. Alving- you fled, fled and refused to return to him, however, he begged and prayed for you.” Mrs. Alving–Have you forgotten how infinitely miserable I was in that first year?

The Priest–What right have we human beings for happiness? No, we have to do our duty! And your duty was to hold firmly to the man you had once chosen and to whom you were bound by holy ties.

Mrs. Alving–You know well what sort of a life Alving was then leading-what excess he was guilty of.

The Priest–But a wife is not to be her husband’s judge. It was your duty to bear with humility the cross which a Higher Power had, for your own good, laid upon you. Yes, you may thank God that it was vouchsafed to me to lead you back to the path of duty and home to your lawful husband.

Mrs. Alving–Yes, Pastor, it was certainly your work! And now I will tell you the truth-after nineteen years of marriage my husband died as much a profligate as he was before you married us.

The Priest–Your words make me dizzy-all your married life the seeming union of all these years was nothing more than a hidden abyss?

Mrs. Alving–Nothing more. My whole life has been one ceaseless struggle. After my son’s birth I had to struggle twice as hard, fighting for life and death, so that nobody should know what sort of a man my child’s father was. I had borne a great deal in this house-I had my little son to bear it for. But when he was only in his seventh year he was beginning to observe and ask questions as children do this was more than I could stand, I thought that the child must be poisoned by merely breathing the air in this polluted home.

How many thousand of unfortunate beings like Mrs. Alving are chained to a life of misery? And for no other reason, than this gravely mistaken sense of duty. They are the victims of old superstition and conventional morality which makes a chattel of the woman from the moment she takes the nuptial vow.

It is to be deplored greatly that these victims are at the time, too frightened and heart broken to tear asunder the ties of an unholy union. The church and the priest–woman’s hope and consolation in the hour of need–were never of much help to her. In the eyes of the church the marriage ties are never to be broken-the priest always manages to exonerate the man and silence the woman.

There is nothing new in Mrs. Alving’s confession, generation after generation of women have fought, felt and lived the sorrows that she knew. It was ever considered woman’s lot to bear her burden patiently, to suffer in silence that the world might not know what sort of a man her children’s father was.

It took the pen of a master hand to give these wrongs their proper expression–Ibsen and the priest, they are both woman’s spiritual advisers. One driving her deeper into the abyss, the other exerting his wonderful power to bring her message of hope, a timely warning. Nobody who ever read “Ghosts” could deny that Mrs. Alving committed a grave mistake by returning to the man she abhorred. If we were to discuss the sanctity of marriage in these lines we would have to acknowledge that it is more criminal for a woman to continue to live with a man whom she knows to be a brute and profligate, than to leave him. For she becomes in time a participant in his crime by bringing innocent sufferers into this world.

It is to save the very children for whom every mother is willing to suffer, it is to save them from the poison Mrs. Alving is speaking about that every abused wife should sever the ties before it is too late. For the very children’s sake she must make an effort to take their existence out of such men’s hands.

What kind of men and women can we expect to grow up amidst surroundings of abuse and dissension? What sort of character will the child, that hears nothing but quarrels and sighs, develop? What can we hope for where spite-work is the slogan, where one parent tries to set the children against the other? “Why wouldst thou be a breeder of sinners?” may well be asked of every woman who realizes that she had taken a wrong step, but who clings, nevertheless, to the ship without a rudder–true enough, in this as in any other phase of life at present the economic question, or the struggle for existence, plays a great role-the majority of women are still tradeless and professionless. The care of the children takes away a great deal of their time, health and energy. The mothers love the little ones who are the flesh of their flesh, the blood of their blood, and therefore fear to deprive them of shelter and food what won der that so many of our good women lead a life of shame and legal prostitution it is to sacrifice for the sake of the children they have brought into life.

But these unfortunate women should not fail to consider the fact that it is not their blood alone that flows in the veins of the children –the traits of the father are more marked in the sons than those of the mother.

Mrs. Alving went back to her husband in order to avoid public gossip. Her child came and she suffered and bore her sorrow in silence for the sake of her babe, never fully realizing her terrible mistake during the year! of her endurance. Only when she sees the same babe grown into manhood make love to the servant maid, his own illegitimate half sister, she understands for the first time the full tragedy by her own action and the first word to escape her throat is “Ghosts.” She sees the ghosts of those who have passed away. The priest makes an effort to convince her that she at least is not to blame for anything, that her own marriage was performed in accordance with law and order.

“Oh, that law and order!” exclaimed the unfortunate woman. “I often think it is that which does all the mischief in the world. I ought never to have concealed the facts of Alving’s life, but I was such a coward! When I heard Regina and Oswald in there it was as though I saw ghosts before me. But I almost think we are all ghosts. It is not only what we inherit in our fathers and mothers that “walks” within us. It is all sorts of dead ideas and lifeless old beliefs, and so forth. They have no vitality, but they cling to us and we can’t get rid of them.” Mrs. Alving finally realizes the sin and folly of it all-but much too late to be of any benefit.

Ibsen closes the curtain by leaving the unfortunate woman standing before her only son, her hope, her very life. The young man had become incurably insane–the result of the father’s profligate life before the child’s birth. No further exposition is necessary to express the amount of misery which falls to the mother’s lot. And the horror of it is that she is only one of many sufferers who are doomed to similar, and at times even worse sorrows. It is only occasionally, when a work like “Ghosts” appears on the scene, that the average person can have a glimpse at the amount of trouble that womankind bears, because of narrow traditions and economic necessity. Ibsen never gives his readers a solution to the problems he is discussing. He simply places the situation and facts before the readers and leaves them to draw their own morals. His mission in life was that of a bugler. He wanted to awaken the people from their long slumber, give them a glimpse of life as he saw it, and then let them work out their own salvation.

It is perhaps a safe way, and yet it is terrible to think how many millions will have to suffer and perish if we should leave them to await the time when enlightenment will at last place men and women on an equal basis independent of each other and of want in general.

We must by all means teach the suffering woman how to ease her burden today and tomorrow, and every day of her life.

The Socialist Woman was a monthly magazine edited by Josephine Conger-Kaneko from 1907 with this aim: “The Socialist Woman exists for the sole purpose of bringing women into touch with the Socialist idea. We intend to make this paper a forum for the discussion of problems that lie closest to women’s lives, from the Socialist standpoint”. In 1908, Conger-Kaneko and her husband Japanese socialist Kiichi Kaneko moved to Girard, Kansas home of Appeal to Reason, which would print Socialist Woman. In 1909 it was renamed The Progressive Woman, and The Coming Nation in 1913. Its contributors included Socialist Party activist Kate Richards O’Hare, Alice Stone Blackwell, Eugene V. Debs, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, and others. A treat of the journal was the For Kiddies in Socialist Homes column by Elizabeth Vincent.The Progressive Woman lasted until 1916.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/socialist-woman/100800-progressivewoman-v4w39.pdf