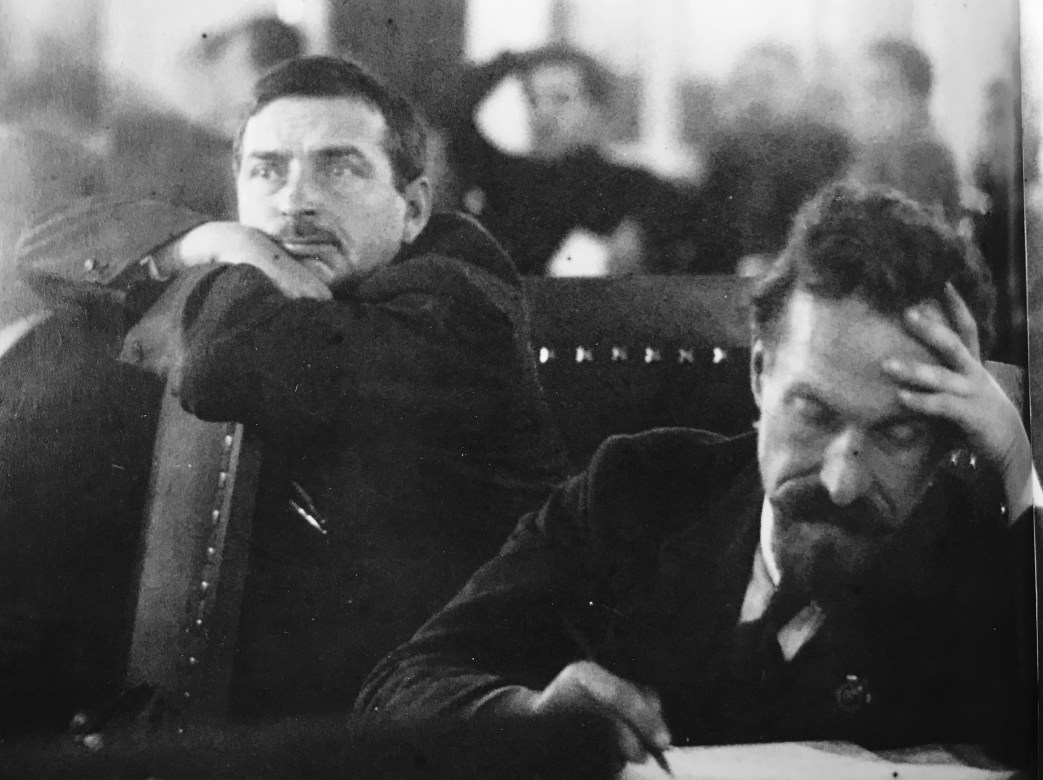

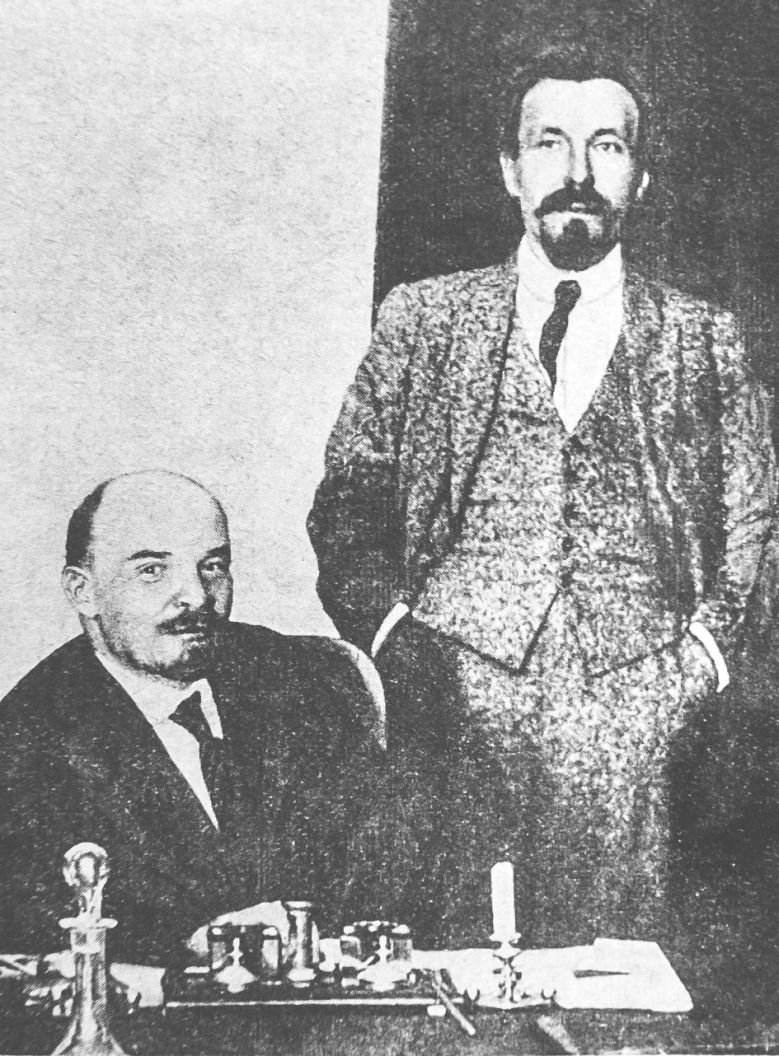

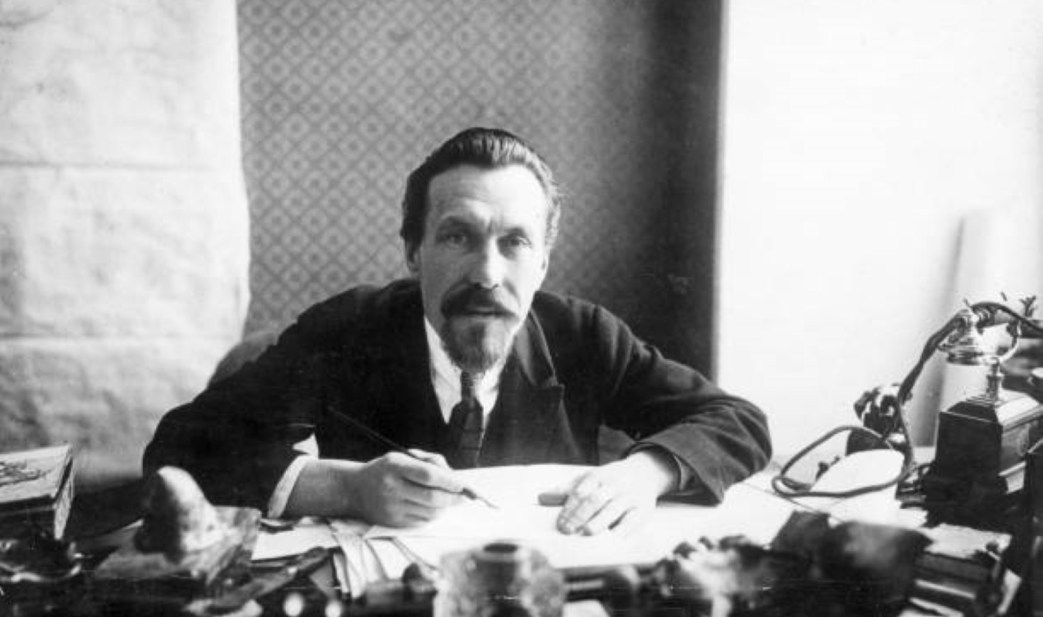

Alongside economic dislocation and restructuring, the early 1920s saw a number of bad harvests, with food production and distribution becoming major task of the Soviets. In 1925 Rykov held Lenin’s previous position as Chair of the Council of People’s Commissars, before that Rykov was Chair of the Supreme Council of National Economy. With Tomsky and Bukharin, Rykov would lead the ‘Right Bloc’ in the Party through the 1920s, losing power in 1929. An accused during Great Purges in the Trial of the Twenty-One, he was executed along with Bukharin, Nikolay Krestinsky, and others on March 15, 1938. He was not ‘rehabilitated’ until 1988.

‘On the Road to a Stable Peasant Economy in the Soviet Union’ by A. I. Rykov from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 5 No. 74. October 15, 1925.

The systematically recurring bad harvests form the worst part of the heritage which Russia of the October Revolution, Russia of the workers and peasants, has taken over from the old Tsarist regime.

Droughts, bad harvests and famine were characteristic of Russia in past times, as for example in the 17th and 18th centuries. In those times the population sought to escape from their misery by mass migration to other and more favourable districts. Russia of the nobles and of the big landowners drove these peasants back again, with blows from the knout, to the parched and barren fields.

There were years, however, in which the rainfall in these districts brought about an excellent harvest, and then the good crops and the abundance of fertile land again attracted the peasants from the more populated and poorer districts.

At present the agricultural population of these districts which are exposed to drought constitute almost a quarter of the total peasant population of the Soviet Union. At any rate, in the year 1921, almost 30 millions of the peasant population suffered from drought and bad harvest. This is an enormous number. Such a tremendous measure of privation deprives agriculture, this important basis of the entire economic development of this country, of any security of return. The bad harvest of 1924 was considerably less, but it affected 7,800,000 of the peasant population.

So long as the conscious will of man, and the organised forces of the Soviet State do not so transform the economic organisation of these districts as to render a recurrence of bad harvests, which devastate millions of peasants undertakings, impossible, so long will the systematic control of the economic and cultural life of the country be interrupted by elementary crises of enormous extent.

Can the peasant economy in the districts exposed to drought be assured of good and regular harvests?

Agronomic science, the experience of agricultural experimenting stations, the experience of co-operative farms and model undertakings say that this is possible.

The failure of the harvests through drought is attributable before all to the backwardness of the methods of farming, the lack of adaptability to the climate, and the lack of organisation on the part of the peasant population. As a result of the united efforts of the Asiatic despostism of the Tsar and of the big landowners, who kept the population in ignorance, and the Asiatic winds which cause the droughts, the Soviet Republic took over in these districts the pre-conditions for violent shakings to the whole State organism. The first and most important aim which has to be striven for after the October Revolution, is to render such shakings impossible.

In the fight against the consequences of the bad harvest of the year 1924 the Soviet power set itself more far-reaching tasks than it did in the fight against the famine. The population of those districts suffering from the drought were rendered relief on such a scale and in such a form as to render them capable of carrying on their peasant undertakings. Great attention, therefore, was devoted to maintaining the stock of cattle of the peasants and keeping the land under cultivation in the districts affected by the drought. In addition to this, large scale credits were organised in order to enable the peasants to maintain their stock of cattle, and the population were given considerable help by means of supplies of seed, with the result that in the majority of cases the area under cultivation in these districts increased in the first years after the bad harvest by 10 to 15%.

But the most important feature of the campaign against the results of the bad harvest of the year 1924 consisted in the fact that, in carrying out this campaign regard was had to impressing upon the peasantry the chief question of a thorough combatting of the causes of the bad harvest.

The measures which must first be carried out in order to avoid the possibility of a recurrence of bad harvests and famine consist in the first place of such a selection of supplies of seeds and such a cultivation of the ground as will secure the stability of the harvest even in cases of drought, secondly, in increasing the importance of cattle breeding, and thirdly, in the carrying through of a distribution of the land and of such a distribution of the peasants that the peasants’ holdings shall be nearer to their place of residence; fourthly, the carrying out of the necessary measures for improving the soil.

All these measures, taken together, mean a complete reconstruction of agriculture in the districts threatened with drought. This reconstruction can only be carried out by means of the active assistance of the population. The activity of our State and economic organs must be entirely directed to bringing about this activity of the population, to help the population to go over to new methods of farming.

It is necessary not only to make every peasant clear regarding the possibility of an organisation by which he would no longer suffer from droughts, but also that every peasant shall realise the advantage of every step which is taken in this direction. All the efforts of the agricultural experts and of the active and most advanced portion of the peasantry will be in vain, if there is not set up in these districts, in a proper manner, an industry for working up the products of agriculture and of cattle-breeding and, what is of special importance, if a market is not organised for the products. The forms of this industry must be strictly adapted to the nature of the agriculture in every province, every district and every locality.

The enormous, inestimable result of the campaign of the years 1924/25 against the consequences of the bad harvest consists in the fact that the apathy of the population, which was caused by the great backwardness of the peasantry, has been overcome. Only in the first weeks after the ascertainment of the actual yield of the harvest was there a certain panic to be discerned among the population, and efforts were made by the peasants to escape from the bad situation by migrating to more favourable districts and abandoning their own holdings. But in a short time, immediately after the arrival of the first relief, the panic died down. The relief received in the way of supplies of seeds entirely changed the mood of the peasants and convinced them that the Soviet government will help them to overcome the bad harvests. Thus there was created the most important pre-condition for the success of all the further work in the affected districts.

The ameliorative work (improvement of the soil), the results of which exceeded all expectations, was particularly popular among the peasants.

In the majority of the affected districts the peasants quite voluntarily carried out a part of the work without payment, as they saw in the ameliorative work the guarantee of good harvests in the future.

For the first time broad masses of peasants faced the question of how agriculture should be conducted, how the soil should be cultivated, how and when seed must be sown, in order to avoid a bad harvest. These questions were discussed at numerous meetings of peasants. The demand for assistance from agricultural experts increased. In all provinces special societies were organised, which were participated in by advanced peasants and agricultural experts, in order to win harvests in the districts suffering from drought.

The campaign against the results of the bad harvest of the year 1924 was a severe test of the whole Soviet system. It was carried out without the creation of any special apparatus in the villages, and the entire work was completely and entirely placed in the hands of the Soviets and of the whole of the peasantry. It can now be recognised that the local soviets have stood this test. They have succeeded in drawing broad masses of the peasantry into work, in reviving such organisations as the “Peasants’ Relief”, in organising the poor peasants, increasing the importance of the co-operatives etc. The “democracy”, in the real sense of the word, that is to say, the population itself, the masses of the peasantry, were the organisers in the fight against the results of the bad harvest in the year 1924/25.

In the future this wave of activity among the peasants in the fight against those two great scourges drought and bad harvests must not be allowed to decline, but on the contrary must be increased in every way and from year to year fresh sections of the peasantry, and especially of the poor peasantry, must be drawn into the struggle.

The chief means of organising the peasantry and their activity must be the co-operatives. The co-operatives are the chief lever for socialist construction in the village. But they are confronted with very extraordinary tasks in the districts suffering from drought and in the black soil district.

The wholesale decline of agriculture must have led to a differentiation of the peasantry, to the formation of a small group of well-to-do and rich peasants alongside of a great mass of poor peasants. The village poor and the middling peasants must find in the co-operative that organisation by means of which with their united forces they will achieve results which are unattainable by individual undertakings.

The activity of the agricultural experts, of the agricultural experimenting stations and of the model farms must not only obtain help of every kind in the system of Soviet and co-operative organisations, but must find there also that social milieu which makes every achievement of science, tested by experience, the common property of the masses. Of course, the transition of the peasant holdings to new methods will be accompanied in these districts by considerable difficulties, and will here and there experience partial failures. But all these difficulties and failures will be overcome with greater’ ease if we succeed in breaking down the conservatism of the peasants, in awakening their energy and in helping them to adopt new methods.

The fight against the bad harvests and the drought is not to be carried on in the bad years of famine, but precisely in the years of good harvest. This fight cannot be carried out in a single year or in a single campaign, but must be conducted with tenacity and perseverance for a whole number of years.

The Third Soviet Congress of the Soviet Union, realising the gigantic nature of the problem, decided to create the basis for ensuring harvests in the districts exposed to droughts and to establish a special fund for this purpose.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1925/v05n74-oct-15-1925-inprecor.pdf