Bertram D. Wolfe was a leader of both the U.S. and Mexican Communist Parties during the 1920s. From 1923 Wolfe lived in Mexico, was active with the railroad union (he was also on the Execution of the Profintern) and on the Executive of the Mexican C.P. In 1925 Wolfe represented the Mexican Party at the Fifth Comintern Congress. Upon returning to the U.S., Wolfe headed the U.S. Party’s ‘Latin American Department’ as well as leading the New York Workers School where he taught classes on Latin American History. In 1928, Wolfe was U.S. delegate to the Sixth Comintern Congress where he gave this major report on the region that throughout the 1920s had seen both the growth of U.S. imperialism and of powerful revolutionary movements.

‘Latin America and the Colonial Question’ by Bertram D. Wolfe from The Communist. Vol. 7 No. 10. October, 1928.

…On the question of “decolonization”: The complexity of the subject and the impossibility of treating it in detail within a short time make it necessary for me to limit myself to the most general and compact statement of viewpoint possible. We must at least take into account the following basic features of capitalist colonial development:

1. There exists a general tendency of capitalism to draw the entire world into the train of capitalist production, to destroy the earlier forms of economy and to introduce capitalist conditions throughout the world.

2. This tendency is undoubtedly strengthened by the export of capital.

3. To bring the whole world into the orbit of the capitalist system, however, does not necessarily mean that all sections of it need be industrialized. Capitalist market relations, plus imperialist rule, plus capitalist agricultural relations would also satisfy this tendency. The essential, the basic industrialization in a country is the development of those industries which produce industries, those industries which produce means of production.

4. In addition to this basic general tendency towards the development of capitalism throughout the world, imperialism expresses a direct counter-tendency; namely, to intensify the parasitic exploitation and the restrictions upon the development of the backward portions of the world.

5. There have been two periods in the development of modern economy when this restrictive tendency was dominant. These periods were the period of early monopoly out of which modern capitalism grew, the period of “mercantilist” theory and “mercantilist” policy in regard to the colonies; and then the period of modern monopoly, the period of monopoly on the basis of finance capital, the export of capital and trustification.

6. While the industrialization and the production of capitalist conditions in the backward nations is growing in an absolute sense of quantity, of the quantity of industry that we find in the world, still in a relative sense and in a sense of discovering the basic tendency of capitalism — the parasitic restrictive aspect of imperialism is the dominant one.

7. The so-called “decolonization” tendency of capitalism is to such an extent counteracted by the parasitic restrictive tendency of imperialism that we even witness a tendency towards RECOLONIZATION; or, better, towards colonization in the sense of reducing previously independent regions of the world, some of them with comparatively developed capitalist conditions, to the status of semicolonies. We have had, in the post-war period, the growth of a whole series of such new semi-colonies where there was no question of colonial status before. Even industrially developed countries, in some cases, come for shorter or longer periods under the control of first-rate powers to such an extent as to assume certain features of semi-colonial status.

8. Of the two tendencies, that is of the tendency to further the industrial development of the backward portions of the world and the counter-tendency to hinder, restrict, and prevent this industrial development, the latter is undoubtedly dominant. The fundamental in this period of monopoly, in this period of finance capital and capital export, is not, as Comrade Bennett and some of the other speakers have said, the industrialization tendency, but the parasitic exploitation tendency of the countries which export capital. To miss this, is to miss the fundamentally parasitic role of imperialism. To hold the opposite theory, to hold the theory that the dominant tendency of imperialism is to develop modern production in the backward portions of the world, would lead objectively towards an underestimation of the oppressive reactionary role of imperialism, of the necessity of and the sharp explosive force of the struggle against it. Carried to its logical conclusion, it leads objectively to an opportunist and even an unconscious apologetic line in the question of the role and character of imperialism.

9. The contradiction between these two tendencies is one expression of the antagonism between metropolis and colony.

10. This antagonism together with the class struggle within the various countries, and together with the antagonism between the imperialist powers and between them and the Soviet Union, will lead to the destruction of imperialism long before this ideally conceived industrialization of the world is completed or has progressed basically far. Only socialism will complete the task but on a new basis of division of labor and planned economy on a world scale. So much on “decolonization.”

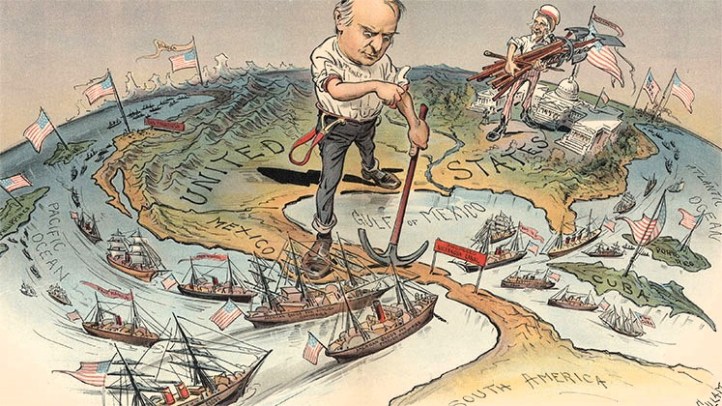

ROLE OF IMPERIALISM IN LATIN AMERICA

I want to turn now to a particular sphere of “colonization” where the imperialism of the United States is creating new colonies and semi-colonies. I refer to Latin America. Certainly here also both tendencies are observable. But, again there can be no question as to which is dominant.

It is perfectly true that the United States, in certain countries of Latin America, has found it necessary to overthrow certain reactionary forces. But not because the U.S. is playing an essentially progressive role. The reason is a historical one; namely, that Great Britain got into those countries first; that Great Britain picked in advance the best natural allies for imperialism in those countries,— namely, the landowners and reactionary Catholic church.

When the United States came into the field to challenge Britain’s privileged position, it was faced with the accomplished fact of the union between landowners and Catholic reactionaries with British imperialism, and in order to break ground for the forward march of the dollar it was necessary to further certain revolutionary forces in those countries. However, just as soon as Britain’s puppet governments were overthrown, the United States tried to stem the tide of the revolutionary development which it had helped to set loose. On the contrary, where the United States is free to choose its allies, in those countries in Latin America where it can take its pick, it links up with the semi-feudal, Catholic land-owning reaction and all the most backward class forces in the country. Thus, for example, we find in a whole series of countries that the United States sets up a fascist dictatorship, that it sets up autocracies of the most brutal sort. I refer to such countries as Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Chile.

To turn to another field, we find this “progressive” American imperialism, so far as Liberia is concerned, attempting to go back to a system of chain-gang, chattel slavery.

Now a few general remarks on Latin America. First, the situation in Latin America presents us with a whole series of new forms of semi-colonies of various grades and kinds, most of them maintaining their formal independence while this formal independence comes to mean less and less as the power of the United States grows greater and greater.

U.S. INTERVENTION IN LATIN AMERICA

Secondly, American imperialism has invented or further developed many forms of intervention. We can distinguish the following:

1. Military intervention, primarily in Mexico and the Caribbean countries. In those countries we have witnessed no less than 30 interventions by military forces in a period of a quarter of a century.

2. Customs control. The Orient is not the only portion of the world where the customs of so-called sovereign countries are controlled by imperialism.

3. Direct fiscal control of bank appointees who are nominated by the President of the United States and formally approved by the puppet governments.

4. Military advisers.

5. (and most interesting) The financing of revolution and of reactionary dictatorships.

The third general observation I wish to make on Latin America is that the general progress of American domination is from north to south, from near to far, from the Canal to the Straits of Magellan. Of course, it is not a regular march; there are jumps in the picture. For example, a country may be overlooked for a moment, if in another country a little further off, oil is discovered. Certain countries were temporarily overlooked in order to make the jump into Chili for the copper and nitrates and other mineral wealth there. But the general march is north to south.

My fourth observation is that this march involves not only a struggle with the peoples of Latin America but also a struggle with British imperialism. A few figures to indicate the character of that struggle.

The United States has at the present time something like $5,200,000,000 invested in Latin America. If we add Canada we find that the United States has invested in the New World—so-called— something over eight billions, out of a total of 13 billions which is invested in the world as a whole, exclusive of the war debts.

To date the United States has invested in Latin America an amount almost equal to Great Britain. You can calculate both of them in round figures at about 5 billion dollars; but the interesting thing about this apparent equality is that before the war Great Britain already had 5 billion dollars invested in Latin America, and has today only $5,200,000,000, whereas the United States before the war had only $2,200,000,000 and has now equalled Great Britain. In other words, we find Great Britain’s power in Latin America, as measured in economic terms, virtually stationary, whereas the Yankee dollar marches with giant strides.

The fifth point I want to underscore is the importance of Latin America in the scheme of economy of the United States, and also its importance in the coming war period. Take oil. Venezuela today, with its oil resources scarcely touched, is the second biggest producer of oil in the whole world; the first being the home territory of the United States. Mexico is the fourth, Colombia and Peru have scarcely been opened up and are rich in reserves of oil. North Argentine and a section of Bolivia also show oil deposits. Metals— every precious metal and every non-precious metal—are found in rich abundance and in forms easy to extract. Raw materials of importance in making munitions are potassium and nitrates. There is rubber and, of course, agricultural products.

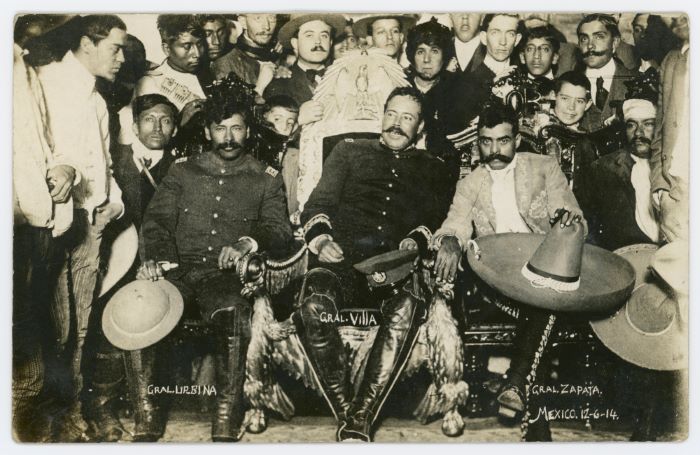

REVOLUTIONS IN LATIN AMERICA

Sixth, a word as to the revolutions in Latin America, as to their character and their content: The Latin-American revolutions belong to the bourgeois democratic revolutions. They represent a close fusion of revolutionary movements primarily agrarian, with the struggle against American imperialism. However, the basic driving force in these revolutions is not the bourgeoisie, but the workers and peasants. This explains the vague socialist aspirations which are continually being expressed in these revolutions. It also explains the socialist phraseology, the radical gestures of the petit-bourgeois governments that take advantage of these revolutionary forces for their own purposes. Socialism in some parts of Latin America is as fashionable today as it was in continental Europe before 1848. All of the various forms of socialism mentioned in the Communist Manifesto you will find in Latin America: petit-bourgeois socialism, feudal socialism, bourgeois socialism and utopian socialism along with the genuine proletarian socialism of the communist movements that are developing in these countries.

I give only one example. During the electoral campaign of Calles and Angel Flores for the Presidency of Mexico, Flores, who represented the landowning Catholic reaction with the support of British capital, posted all over the country a placard with his picture and the words, “I am a socialist and a revolutionary.” You can imagine what revolutionary phrases the “socialist” Calles used if that was the character of the propaganda of the reaction. In this connection I quote a warning of Lenin’s which applies to the Latin-American comrades. He said:

“It is necessary to carry on a determined struggle against any attempt to cover with a communist mantle the not truly communist revolutionary emancipation movement in backward countries.”

We have in Latin America, for example, such dangerous careerists as Haya de la Torre of Peru who came to Moscow, who attended the Fifth Congress of the Comintern as a fraternal delegate, who came to the Third Congress of the Profintern as a regular delegate, and who has attempted to cover with the mantle of communism an essentially non-communist movement, and in this case, a dangerous careerist personalist movement.

Or, take the movement represented by Carlos Leon of Venezuela. I don’t want to mention them in the same breath because Leon is not the unprincipled type of careerist that Haya de la Torre is but here also is a tendency to cover with the socialist mantle a movement that is not socialist in character although the proletariat may support it.

CLASS FORCES IN LATIN AMERICA

Seventh, a few additional remarks as to class forces in Latin America:

(a) We must not, in the first place, forget the great weakness of the national bourgeoisie in most of the Latin-American countries. All important industries, in most of these countries, are in the hands of foreign capital as are the banks, means of communication, etc. Thus in Mexico, in the field of petroleum, the investment of native Mexican capital comes ninth on the list and even Cuban capital has more money invested in Mexican petroleum than have native Mexicans, Cuba being eighth. This weakness of the native bourgeoisie helps to account for the greater role played by the petit-bourgeoisie in Latin-American revolutionary movements.

(b) We must note the peculiar character of certain sections of the Latin-American petty bourgeoisie. Intellectuals who are partially declassed, play an important role out of all proportion to their numbers in the movements of Latin America.

There are two basic reasons for the existence of discontent among the intelligentsia of Latin America. One is that foreign imperialism in general, and American imperialism in particular, tends to maintain autocratic governments in power for indefinite periods, until these degenerate into cliques of superannuated bureaucrats who leave no room for the young intellectuals turned out by the universities to find a career in the important sphere of government. This was one of the driving forces which made the students and the young intellectuals of Mexico virtually unanimous in their opposition to Diaz and his group after they had been in power for thirty years. A similar situation exists in countries like Venezuela, Peru, etc. Secondly, there is the tendency of American capitalist enterprise to employ as technicians, engineers, overseers, etc., Americans who are brought into the country especially for the purpose so that the only other field that might be open to intellectuals is thereby closed to them by imperialism. They have only one remaining field of activity, namely, opposition politics and anti-imperialist politics and into this they tend to enter. They represent, however, a dangerous force, combining with the usual vacillating characteristics of the petit-bourgeoisie and intelligentsia, a peculiar susceptibility to both open and direct bribery, being readily satisfied by a “share” in the government—an opportunity to lay their hands on part of the national treasury, or with employment by American imperialist enterprises as technicians, fiscal agents, etc.

(c) The proletariat in the Latin-American countries, with the exception of the most developed of them, is extremely weak. This is a reflection of the weakness of industrial development in general. Also, even where there is a proletariat developing it is still lacking in experience, organization, technique and discipline, due to the newness of the proletariat as a class. It is closely linked up with the peasantry, often made up of only recently “deruralized” peasants.

This has, on the one hand, the advantage of making easier the leading role of the proletariat over the peasantry, but on the other: infiltrates the proletariat with peasant ideology, making popular a sort of “narodnikism.”

THE LATIN-AMERICAN PEASANT

(d) As to the peasantry, it presents some peculiar features in many of the Latin-American countries which makes it necessary to distinguish sharply between it and the European peasantry. Errors have been made by comrades here, because the concept “peasant” has been taken too mechanically and too literally in a European sense in judging peculiar Latin-American problems. The peasant in many Latin-American countries is not a landowner of even the smallest parcel of land. Economically speaking one might say he is not a peasant at all; he is a former joint owner of communal lands or perhaps even of a small parcel of land on an individual basis, but the process of creating large estates, or dispossessing the peasant Indian communes from their communal possession of the soil; the process of enclosures, has removed him from the land, pauperized him and made him into an agrarian worker, or a rural pauper. However, he retains the tradition of having been possessor of land and the ambition of recovering the lands taken from him or his immediate forefathers. Oftentimes he does not even demand private property in land, regarding it with suspicion and aversion, but demands that the communal lands be restored to the entire village unit or tribal unit that formerly possessed them.

It is this which gives the Latin-American peasant in many countries his peculiar characteristics, (e) Next, there is the complication of race to be considered. There are whole sections of inland countries in Latin America where Spanish is not the language of the people, where there are still vast Indian tribes with strong survivals of tribal organization—often strong enough to be basic and decisive for the social character of their movements. These Indian tribes speak their own language, retain strong vestiges of primitive communism in their tradition and their economy and in some cases have a powerful tradition of former tribal glory. (Incas, Aztecs, Mayas, etc.) They view Europeans and even mixed white and Indian natives of the coastal and more industrialized regions of the country with suspicion and aversion and can rarely be led by those who cannot speak their own tribal tongue. The parties of Latin America in those countries where this state of affairs exists must work out a whole series of special measures to meet these problems, measures involving such matters as self-determination for the indigenous races, special propaganda in their own languages, special efforts to win leading elements among them, special educational activities for those communists who are of Indian origin and who speak the Indian dialect, so that they can go back into the inner regions of the country and organize the indigenous elements.

The history of the last generation in these Latin-American countries where compact indigenous tribes exist, especially where there are mountainous regions which have tended to protect this compactness and semi-independence, is characterized by a whole series of Indian uprisings, sometimes against foreign imperialist oppressors, sometimes against the landowners, sometimes against the native state bureaucracy—generally a fusion in different degrees of these three revolutionary movements. These uprisings constitute the greatest reserve of revolutionary energy that exists in Latin America, which reserve is only very imperfectly connected with the proletarian and agrarian peasant movements of the rest of the countries.

LACK OF PARLIAMENTARY LIFE

(f) Emphasis must be laid on the lack of bourgeois democratic and parliamentary traditions in Latin-American political life and the lack of such traditions and illusions among the masses. The weakness and oftentimes the virtual non-existence of the native bourgeoisie is of course the basic explanation of this. The petit-bourgeoisie makes up the state apparatus and often the officership of the armies. This state and army apparatus plays a large role in the life of Latin America and is one of the means of native exploitation of the indigenous and peasant masses of the various countries. A struggle for control of the treasury is quite literally an important force in the conflicts between the different so-called parties in Latin American life. The “outs” are almost always ready to sell themselves to American imperialism if the British are tied up with the “ins” and vice versa.

(g) As to these rival imperialisms, the conflicts between them often result in liberating revolutionary forces in a country where they are about equally balanced. Neither of them is strong enough to run the country without utilizing some native elements. Each of them supports contrary elements and if one of them is tied up with the reaction, the other one often has to tie up with the progressive elements. The result is a continuous see-saw as manifested in Mexico since the discovery of oil there. We may look for a similar situation now in a country like Venezuela where oil has been discovered in large quantities and where British and American capital are in pretty even balance.

THE PAN-AMERICAN FEDERATION OF LABOR

Eighth: A word on the Pan-American Federation of Labor. When the ancient Spanish conquerors wanted to win what is today Latin America it sent Jesuit missionaries to prepare the conquest ideologically. ‘Today the masses of Latin America are too rebellious for religion to accomplish as much as once it did. A more “radical” ideological weapon is needed. ‘This the American bankers and state department have found in the labor lieutenants of imperialism. The leaders of the American Federation of Labor, Green and Woll and their henchmen, Morones, Iglesias, Canuto Vargas, etc., with their Monroe Doctrine of Labor and their Pan-American Federation of Labor seek to paralyze the fighting will of the Latin-American masses, and pave the way for the new conquest of the continent. Comrade Martinez, a delegate to the Congress, did yeoman’s work in exposing the imperialist role of these new missionaries. But the American and Latin-American parties must many times multiply this work and set up against it the closest union of the working class organizations of Latin America with each other, with the left wing of the American labor movement and with the R.I.L.U.

THE QUESTION OF WORKER-PEASANT PARTIES

Ninth: I think the Congress must categorically reject the proposal for the founding of Workers’ and Peasants’ Parties in the Latin-American countries. Our primary task in Latin America is to establish Communist Parties, build them strong and make their line of demarcation clear. They must penetrate the mass movements of the workers and peasants, and lead these movements. Some comrades have been confused, particularly during the period of the forward march of the Kuomintang. It is one thing when we are faced with an already existing Kuomintang, and have to answer the question as to whether or not we shall work in it, another thing when we create a Kuomintang as an obstacle and a problem. Particularly in view of the weakness of the parties, the political backwardness of the masses, the lack of parliamentary tradition and the excessively big role played by the petit-bourgeois state bureaucracy and the petit-bourgeois professional politicians in Latin America, there is the danger that such elements will get control of the workers’ and peasants’ party. The correct form for Latin America today is the worker-peasant bloc, with penetration and leadership by a steadily developing Communist Party.

THE ARMING OF WORKERS AND PEASANTS

The tenth point concerning the arming of the workers and peasants: In the various struggles against imperialism and against internal reaction in the various countries, the workers and peasants must enter as a separate force. The Communist Party must make clear its own program at every stage, must criticize at every stage the elements with which at times it must cooperate; must struggle consistently for the hegemony of those movements. At the same time we must pay special attention to the organizational form that the struggle manifests. For example, when elements of a still revolutionary character seek the support of the peasants and workers of Latin America, we must put down as one of the minimum organizational conditions the right of those workers and peasants to separate armed detachments under their own leadership, with their own program, and maintaining the status of guerilla forces in the general struggles that take place.

This tactic has been applied with some success in Mexico, and as a result, whole sections of the peasantry are armed today, and, in spite of the repeated efforts to disarm them, they retain their arms. This tactic must be applied to the various Latin-American countries as revolutionary situations are produced.

A NEW WAVE OF STRUGGLE

The eleventh point: There is a new wave of resistance against American imperialism; a new development of revolutionary forces in the agrarian revolution, and all the phases of the revolutionary movement in Latin America. This is particularly marked in the post-war period. I mention only a few instances: the long struggles in Mexico, the revolutionary struggle in Ecuador, uprisings in Brazil, in Colombia, in Peru, in Venezuela, in Bolivia, in Paraguay, in Northern Argentina; the sharpening struggle in Chile, which has only temporarily been defeated by the establishment of a brutal military fascist dictatorship. And above all, the heroic resistance that has been manifested by such little countries as Santo Domingo, Haiti and Nicaragua and the other Central American countries to the aggression of the United States. A recent newspaper carries facts of stirrings in a new quarter. Costa Rica has been quiet for a while, but we find here in an issue of a Costa Rican paper of May 18, 1928, that a motion of interpellation to the Secretary of Foreign Relations as to why they are not recognizing the Soviet Union, and a demand that the United States blockade be broken in this respect, was carried by the Chamber of Deputies. Of course, that does not mean that the Chamber of Deputies has become revolutionary. It means that there are stirrings among the masses, or these petit-bourgeois politicians would never attempt to frame such a demand.

The outstanding example of the new strength of the resistance of Latin America to American imperialism is the struggle in Nicaragua. Never before has Nicaragua, or any of the small Central American countries, been able to put up so brave a resistance for so long a period. For a year and a half, in one form or another, the forces of national liberation in that diminutive country have been holding at bay the marines of the United States and carrying on, with more or less success, incredibly heroic guerilla warfare. Never before has such a struggle awakened so much echo in the rest of Latin America and gone so far towards unifying the revolutionary and anti-imperialist forces for a common struggle.

THE IMPORTANCE OF LATIN AMERICA

In the face of the dominant power of American imperialism in the world today, Latin America assumes more importance than ever; in fact, it moves up to the first rank among the vital questions that concern the entire Communist International. The United States and the Soviet Union represent the two poles of the earth today. Leninism has taught us where to seek and find allies against our most powerful enemies. It teaches us now that the whole Comintern must turn its attention to this natural enemy of American imperialism, this natural ally of the proletariat of the world—the revolutionary movements of the Latin-American peoples.

At the Fifth Congress Latin America was represented by one Party and two League delegates for all of these numerous countries put together. The large representation at the Sixth Congress is an evidence that the Comintern has already turned its eyes in that direction and an evidence also of the rapid development of class relationships in Latin America. But the entire Comintern, and particularly the American section of the Comintern, must multiply by many times its attention and its aid to the Communist Parties and the revolutionary movements of Latin America.

This requires some elementary changes in the Comintern apparatus. I cite only one. The Latin-American countries are still in the so-called Latin Secretariat. Why? Because our apparatus unfortunately is built on a basis of language, in place of common political problems. And therefore Latin America, Italy, Spain and France find themselves in a single Secretariat in which necessarily little or no attention can be paid to the special problems of Latin America. I think that some reorganization must come after this Congress in which common political problems become the basis of grouping, and not common language.

Finally, I want to say that as far as the question of “Latin Americanism,” which has been raised in some of the discussion here is concerned, we cannot slavishly accept the general proposals for Latin-American unity which are made by the petit-bourgeois intellectuals of Latin America. The proposal for a union of all the existing governments and countries as at present constituted in Latin America is a fundamentally false and reactionary proposal, because they include a whole series of puppet governments of American imperialism, and some governments which are still puppets of British imperialism.

We must raise the slogan of the union of the revolutionary forces, the workers’ and peasants’ movements of Latin America with the revolutionary workers of the United States; and we must add to that the slogan of the union of Workers’ and Peasants’ Soviet Republics of Latin America for a common defense against American imperialism, and for a common federation in a Soviet Union.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v07n10-oct-1928-communist.pdf