An attempt by William Randolph Hearst (spit) to break the unions in the Chicago papers led to a bitter six month strike/lockout in 1912 that resulted in four deaths as the bosses brought in scabs, deliberately fanning racism. Centered on the pressmen, the struggle grew to include stereotypers, deliverers, the mass of newsboys, and others. Craft union divisions helped sink the strike with only the pressmen holding out; eventually to be replaced by non-union workers. Phillips Russell reports on the the beginnings of the conflict.

‘The Newspaper War in Chicago’ by Phillips Russell from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 31 No. 1. July, 1912.

AFTER two months to think it over, the Chicago newspaper publishers now probably realize that they һаvе bitten off more than they can chew. The trades which they forced to strike the first of May have proven just a little bit stronger than even the much vaunted “power of the press.” They are now in the same fix that the little boy who took hold of an electric battery found himself in—they wish somebody would come along and help them let go.

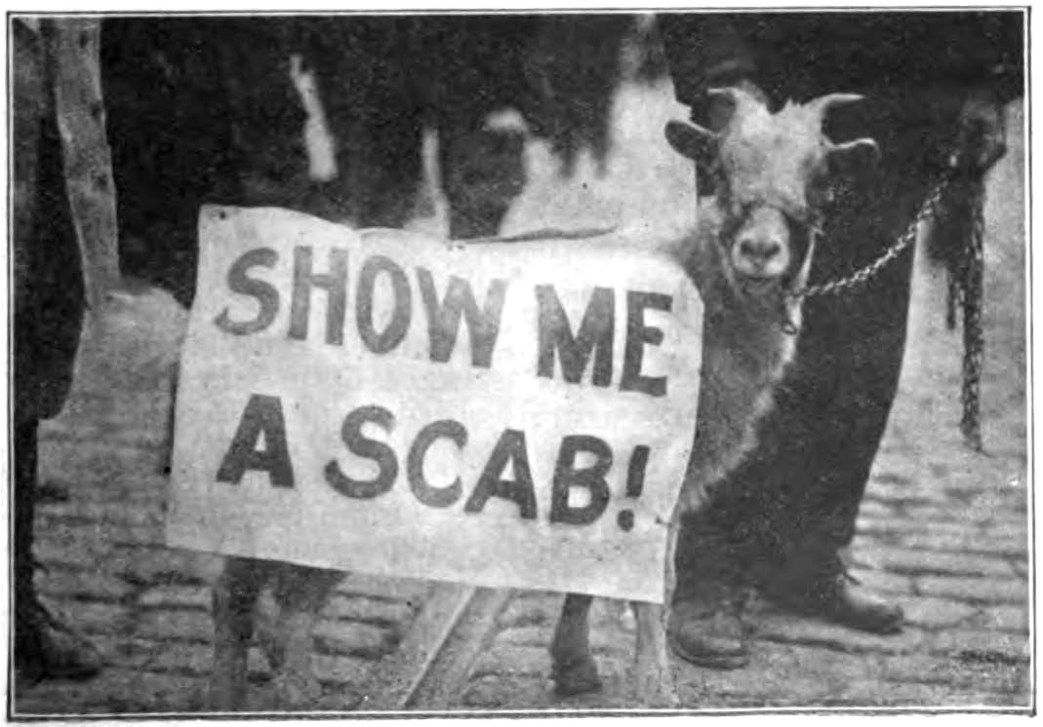

The printers having decided to stay at work and scab, the capitalists of the black headline could probably have beaten the single craft of pressmen, and the stereotypers too, but they failed to take account of another factor in the battle—the newsboys. The publishers safeguarded the production but failed to make secure the distributing end. They thought they had the newsboys tamed after years of oppression. But they were mistaken. Two days after the pressmen were thrown into the street, the newsies hit the organized publishers of Chicago a blow that rattled their teeth. They refused any longer to sell the capitalist newspapers. They were soon followed by the drivers, who refused to handle the reins on scab delivery wagons, and by the circulators, the boys who deliver papers to residences.

From that time on these young fellows had to bear the brunt of the fight. Their position was right on the firing line where they were called upon to withstand the incessant assaults of the enemy.

The publishers were not long in hitting back. Andy Lawrence, W.R. Hearst’s chief hired man in Chicago, rushed to Mayor Carter Harrison’s office and demanded that the city streets and the police department be turned over to the newspaper publishers. The mayor complied with alacrity and all the powers of the municipal government were immediately placed at the disposal of Hearst and his fellow plutes of the printed page. The spectacle that followed was of the most brazen description, but so accustomed are our “free-born American citizens” to this sort of thing that it was accepted as a matter of course.

Chicago took on the appearance of a city in a state of siege. Bluecoats were thick upon every corner and a powerful cordon of police and detectives was thrown about that gorgeous structure, the Hearst building at Madison and Market streets. This and surrounding cities were scoured for scabs, but the response at first was slow and for several days almost no capitalist papers could be had on Chicago streets. The loss to the publishers must have been enormous. Consequent upon the shrinkage in circulation, the pulling power of the advertisements of big stores began to weaken and the merchants began to put up a howl. This spurred the publishers to renewed efforts and negroes, old women, and small girls were put out to fill the places of the newsboys.

Collisions resulted and the negroes were soon withdrawn, but the women and children were kept at the stands. This was a cunning trick on the part of the publishers, since the women and girls were used both to excite sympathy and to act as shields.

Not only did the city administration throw a protecting arm about the poor, worried publishers but opened an aggressive campaign against the newsboys. Wholesale arrests of the striking boys were made on a charge of “disorderly conduct” and many of them were brutally beaten and slugged. An old city ordinance against street cries by peddlers was dug up, dusted off, and made to apply to the newsboys and thereafter any union boy who called his extras was immediately arrested and jailed.

The news-stands which the boys had used for years were taken away from them and squads of policemen were sent over the city to see that this order was enforced. Newsies who had long occupied certain corners suddenly found themselves without even a shelf on which to place their heavy bundles and were forced to lay their papers on the curbing where they were quickly soiled by the dirt and mud of the streets. They were prodded and harried incessantly by the police and by the army of city detectives and privately hired spies and strong-arm men.

Nothing was left undone to make life miserable for the boys and to prevent them from making a living. For example, the boys had long handled the Saturday Evening Post on their stands. Suddenly the boys were. informed that no more copies of the Post would be supplied them and thus another source of revenue was cut off. It was found that the publishers had brought pressure to bear on the Saturday Evening Post people and had stopped the delivery contractor in Chicago from supplying the boys with any more copies.

But despite the almost ceaseless persecution, the newsboys held their ground. Through all the threats, arrests and beatings to which they were constantly subjected they stood steadfast. Finding that brutality would not’ win for them, the publishers adopted oily smiles and sent emissaries to make overtures to the boys, who replied that they would return to work when the other trades did and not before.

Most of them managed to make a living by selling the Daily Socialist which changed its name to The World, with morning and evening editions. But the demand for union papers was far greater than the World was able to supply and there were many boys who found their means of livelihood almost gone. Then they found they could do well with the INTERNATIONAL SOCIALIST REVIEW and sales of the Socialist monthly helped out earnings considerably. A brisk demand soon sprang up and the REVIEW was put on sale in parts of the city where it had never been seen before. Even in the heart of the financial district the REVIEW sold surprisingly well.

There was a comic aspect to the efforts made to protect the “finks” who sold the capitalist papers. It was a common sight to see one foot policeman and one mounted cop guarding a single scab stand and in the early days of the fight it was not unusual to see three or four cops both in uniform and plain clothes guarding one trembling little fink.

But business for the publishers remained poor and to stimulate sales the cops themselves began selling the scab papers. Prodded on by orders from above, the scabbing coppers made every effort to induce the public to buy the wretched sheets that purported to be newspapers, even interfering with sidewalk traffic in their attempts to make sales. The day’s work done many cops forced the “finks” to hand over half of their receipts.

But despite all these numerous devices, great dents and holes were made in the circulation of the capitalist papers. In some parts of town it was impossible to buy a scab sheet and in the working class districts, where the Hearst papers had always been strong, no one would touch a copy. Severe fines were imposed by many unions on all members caught reading a scab paper.

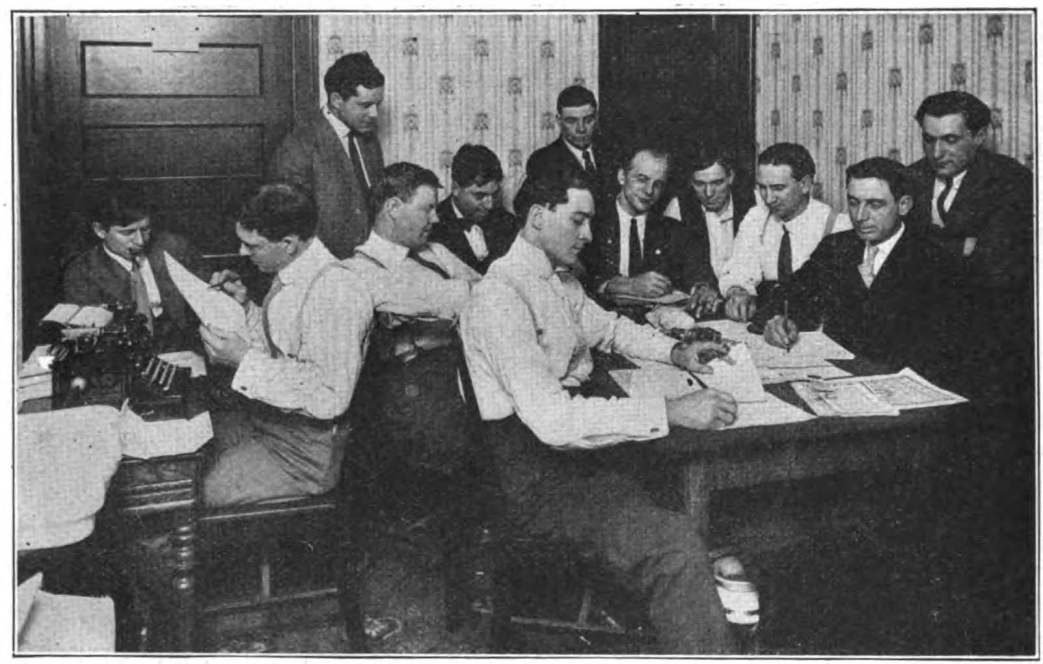

For purposes of defense, the newsboys joined the other locked-out unions in forming the Federated Newspaper Trades. A committee was organized to conduct the strike, composed of L.P. Straube of the Stereotypers, William O. Kennedy of the Drivers, W.C. Cotton of the Pressmen, and Dave Pacelli of the Newsboys as officers, together with three representatives of each trade involved, and one representative each of the Chicago Federation of Labor, Franklin Pressmen’s Union No. 4 and Printing Pressmen’s Union No. 3.

An able general was Tony Ross, President of the Newsboys’ Protective Union, who started selling papers when he was eight years old. He was assisted by Secretary Maurice Racine, and Business Agent David Pacelli. Regular meetings were held and the publishers were notified that the newsboys would not settle until prices had been made satisfactory and papers made fully returnable under a five-year contract.

The newsboys have had abundant cause for bitterness against the publishers of Chicago’s “great” newspapers. Previous to their organizing four years ago they were kicked about and abused at the pleasure of the circulation managers and were in daily fear of their lives during Chicago’s notorious “circulation war” when each newspaper, from the respectable Tribune to the saffron Examiner, hired sluggers who made almost nightly raids on rival newsstands and made brutal assaults right and left.

This was finally stopped, the newspapers forming a sort of trust agreement not to fight each other any more, but with their combined power they began to put the screws on the newsboys, who were compelled to take not the number of newspapers that they wanted but that the hired man of the publishers decided they should be forced to take.

It was a common thing for a boy to ask for 100 papers, for instance, and be forced to take 150 or 200, for which he would later be called upon to settle. Division men, such as Hearst’s man Bill Hellard, “pride of the stockyards,” and Bob Holbrook, of the Journal, would call around and inform the boys that “you gotta take twice as many papers tomorrow night or we’ll put somebody else on dis stand.” Boys who failed to take heed were refused further papers or forced to sell their corners to men favored by the combined publishers. Assaults were common. А typical case was that of Mike Marino, who had a stand at Wells and Kinzie streets, only a short distance from the Review office. The Journal forced extra copies upon him till Mike revolted. He and a Journal driver got in an argument about it. The driver was the larger man and Mike, in fear for his life, got a gun and shot him. Such things explain why the newsboys are determined to hold out to the bitter end.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v13n01-jul-1912-ISR-gog-ocr.pdf