1924 was a year of intense factional struggle in the Workers (Communist) Party over the Farmer-Labor Party movement and Robert LaFollette’s Third Party moves. Making many accusations of opportunism by the Ruthenberg/Lovestone/Pepper faction, in essence Foster argues that there was now no mass sentiment for a Labor Party and attempts to revive the Farmer-Labor Party without union backing was an opportunistic ‘get rich quick’ scheme, as the Communists would be leading a reformist party. Rather, the focus should be on building the Workers Party. For their part, the Ruthenberg faction accused the Foster/Cannon/Bittelman faction of opportunism towards LaFollette’s forces. The factional fight would, in one way or another, last the rest of the decade.

‘Farmer-Labor Opportunism’ by William Z. Foster from the Daily Worker Saturday Supplement. Vol. 2 No. 233. December 20, 1924.

THE campaign of the Workers Party to establish a farmer-labor party was the major united front manouvre of our party up to date. On the whole, despite some decided disadvantages which will be touched upon in this article, it was beneficial to our party. It put the Workers Party at the head of large masses of workers in motion and gained for it much prestige as the fighting party of the working class. It gave us an opportunity to acquire much skill in the handling of these masses and enabled us to make them at least partly acquainted with Communist principles and tactics. It gave our own party membership a realization that the Workers Party, altho a small party, can become a real factor in the class struggle by following a militant policy.

But this farmer-labor party campaign was carried out under exceedingly difficult circumstances. The sentiment for a farmer-labor party of industrial workers and poor farmers, distinct from a LaFollette third party, was weak and vague, and almost the entire trade union bureaucracy was opposed sharply to the farmer-labor party. The problem of driving wedge between the “class” farmer-labor movement and the LaFollette movement proper, and of organizing a farmer-labor party in the teeth of official trade union opposition, was a great one. The burden of leadership in the movement fell almost entirely upon the membership of the Workers Party. Naturally many mistakes were made. Some of these were of an opportunistic character.

In their desperate efforts to breathe the breath of life into their dead “class” farmer-labor party slogan, the farmer-labor Communists of the minority, especially Comrades Ruthenberg and Minor, have singled out some of these incidents and, upon the strength of them, have denounced the Central Executive Committee as opportunist. They conveniently overlook far more serious mistakes made by themselves when they were the C.E.C. It is the purpose of this article to discuss the various mistakes in our labor party policy to place the blame for them where it belongs, and to draw the lessons from these mistakes for our future work.

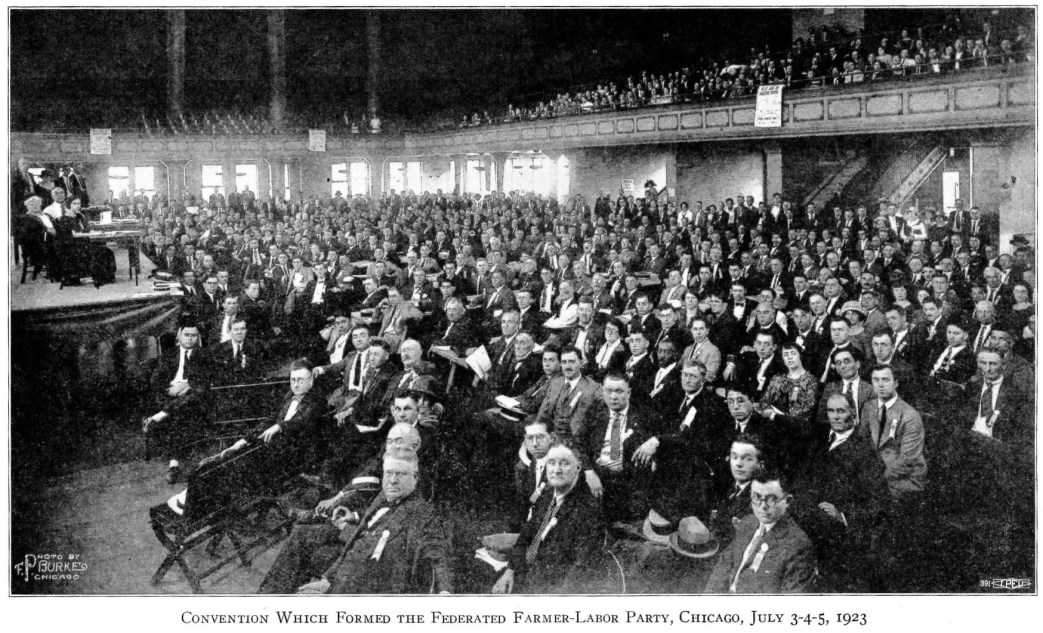

The Chicago July 3rd Convention

The W.P. policy in this convention, mapped out by the present minority, which was then the C.E.C., was highly opportunistic. The basis of the convention was a united front from above, between the leaders of the Workers Party and the farmer-labor party. At the last W.P. convention comrades Pepper, Ruthenberg, and Lovestone made the welkin ring with complaints about the Chicago united front, but they themselves engineered this phase of it, the one section that was really open to serious criticism.

Perhaps the biggest mistake made at the convention was pressing to the point of a split the question of the immediate formation of a farmer-labor party. Experience later with the filmy federated farmer-labor party, which was formed at that time, showed that this mistake originated in an opportunistic grasping for the masses. The former C.E.C., in their eagerness literally to grab off a mass party, over-reached themselves. For this they were censured in the latest decision of the Communist International on our labor party policy, as follows: “The Workers Party failed in developing sufficient pliability with regard to so-called progressive elements and did not devote, and does not yet, devote, enough attention to the work among the workers organized in the labor unions.” Former endorsement of the split by the C.I. were based on reports that the split resulted in a party of 600,000 workers and poor farmers.

Other sharply opportunistic tendencies developed with regard to the program of the F.F.-L.P. A committee entirely controlled by the W.P. presented to the convention a program so conservative in character that it, was acceptable to the most reactionary elements and was adopted unanimously. (Comrade Pepper was especially pleased with the “courage” of our party in supporting the petty-bourgeois money plank which was supposed to win for us the support of the farmers). Comrade Pepper was pleased over this incident, almost as much so as some months later when he heard that our comrades in Minnesota had decided to vote for Magnus Johnson. He declared that we must have such errors in the platform, because behind this confusionism stands great masses, and of course we had to cater to catch them. Another fine sample of the opportunism of the former C.E.C. at the Chicago convention was the failure to introduce a resolution for the dictatorship–it was feared it would pass and break up the show.

The August Thesis

Among the very worst opportunistic development of the W.P. labor party policy stands the so-called August thesis. This was the chef d’oeuvre of Comrade Pepper, a master opportunist, the shrewdest yet produced by the American Communist movement, and one who understood how to cover up his opportunism with a heavy mask of revolutionary phraseology. His August thesis, enthusiastically supported by the former C.E.C., proposed a sort of get-rich-quick scheme. It was a very seductive “short-cut” to the revolution. Its essence was that the Communists should, by a grand manouvre, sort of sneak up unsuspected upon the labor movement, tear off a great section of it and become overnight the leaders of a mass-movement.

The August thesis proposed the wonderful and opportunistic scheme of two mass Communist parties in this country. One of these, the federated farmer-labor party, was to consist of a general mush of trade unions, singing societies, fraternal orders, hiking associations, self-advancements clubs, etc., and its function was to carry on an opportunistic campaign amongst the workers on the basis of their immediate demands. The other Communist party, the Workers Party, was to stand modestly in the background, serving to salve our revolutionary consciousness and to propagate Communist principles in the abstract.

The present C.E.C., then the minority, fought the August thesis unrelentingly. They forced its advocates to lay it on the shelf. At the last W.P. convention, the defenders of the August thesis lacked the moral courage to make a fight for it. They evaded the issue. But they still have this thesis definitely in their minds. It is the basis of their labor party policy. Comrade Minor admits this frankly in a recent article.

Comrade Pepper’s political stock gamble, as exemplified by the August thesis, was sharply condemned by the C.I. in its recent decision on the American farmer-labor policy. In the face of Comrade Pepper’s vigorous opposition, Comrade Olgin and I made war against the August thesis in Moscow. The result was that the following paragraph in the decision, which is entirely in accord with the policy of the present C.E.C., was proposed by comrade Kuusinen and adopted unanimously by the presidium:

“7. The aim to strive at is not to split the left-wing from the labor party as quickly as possible in order to form this split off party into a mass Communist Party. But we must strive at letting the left wing grow within the labor party and at the same time at taking in its most advanced and revolutionary elements into the Workers Party.”

The Third Party Alliance

Another opportunistic sin on the political soul of the present minority was the so-called third party alliance. This was another product of Comrade Pepper’s fertile opportunism. In common with many others, the present C.E.C. fell victim to it. It was my hard task to defend it in the Comintern. No sooner did I hit Europe and explain it to the first revolutionist I met than I encountered a drastic condemnation of it as most dangerous opportunism. And so it continued all the time I was on the continent. Never on my whole trip, in Russia and elsewhere, did I meet a single Communist who did not wholeheartedly repudiate this proposition. The action of the Comintern presidium was unanimous in rejecting it as a manouvre unfit for the Workers Party to make. There is no need here to make further argument about the opportunism of the third party alliance. This is admitted everywhere except in the thesis of the minority. The corrective action of the Comintern in this matter saved our party from serious difficulty.

In passing it may be noted that the three grand labor manouvres engineered by comrade Pepper and the former C.E.C., namely the Chicago convention, the August thesis, and the third party alliance, were all condemned by the Communist International in its latest decision on our labor party policy.

The Grab at the Farmers

Another opportunistic manouvre by the former C.E.C. was the adventure among the farmers. The split at the Chicago July 3rd convention cost the Workers Party many valuable rank and file union connections in the various industrial centers. It dampened the labor party movement there very much. Just about this time comrade Pepper discovered the impending “LaFollette revolution,” the back- bone of which were the farmers, then in a strong state of ferment. Immediately in the policies and statements of the former C.E.C. the farmers emerged as a great, if not the great, revolutionary factor. The party turned its major attention towards working among them, the more difficult work among the trade unions being sadly neglected.

Largely forgetting that the industrial workers must of necessity be the base of our party activity, they shifted the center of gravity to the farmers. The trade unions were systematically minimized, the whole A.F. of L. being denounced as simply an organization of labor aristocrats, notwithstanding the great numbers of miners and other genuine proletarian elements amongst the unions. Efforts were made to minimize the importance of the working class itself in the revolution and to prove that the United States is more of an agricultural than an industrial country. In Moscow Comrade Pepper even went so far as to state that in respect to its industrial development the United States resembled Russia more than it did England.

The Workers Party must win the support of the poor farmers. They are essential to the success of the revolution. But this support must not be won by the sacrifice of real proletarian support. Realizing this, the present C.E.C., then the minority, carried on a ceaseless struggle to keep the heads of the former C.E.C. from being turned altogether by the “easy pickings” amongst the farmers and from neglecting the far more vital work amongst the industrial workers. The opportunism of the former C.E.C. ran riot in connection with the farmers.

The St. Paul Convention

Then we came to the St. Paul convention. In this connection the farmer-labor Communists raise loud out-cries of protest. After having been guilty of the gross opportunism of the Chicago split, the August thesis, the third party alliance, and the grab at the farmers they venture to call the present C.E.C. opportunistic. The situation at St. Paul was this: The elections were approaching and it was absolutely necessary to crystallize the farmer-labor party in order to make, or try to make, a campaign under its banner. The situation was difficult, with the LaFollette forces sucking the life out of the farmer-labor movement. Consequently the C.E.C. made extreme efforts to hang on to the disappearing masses. In some respects its policy verged into opportunism. This must be admitted. But the minority are disbarred from criticism. They endorsed the whole thing.

Comrade Minor blossoms forth with a speech I was supposed to make in St. Paul. The fact is the speech was imperfectly reported. But it was bad enough at the best. I make no apology for it. It represented only one of the overstrainings we made to retain contact with the masses. But the speech was in harmony with the point of view of the whole C.E.C. majority. Comrade Ruthenberg, who was on the steering committee that authorized it, pronounced it very timely. Not a word of objection was raised by the minority, altho the C.E.C. was meeting nightly. It was only a couple of months later, when word was received from Moscow, that the minority woke up to a realization, for factional purposes, that the speech was opportunistic.

Comrade Ruthenberg also voices a protest against our opportunism. He cites a motion that I am supposed to have made in the C.E.C. to the effect that we should support LaFollette’s nomination. But Comrade Ruthenberg has developed much a penchant for writing the minutes in a factional spirit that the C.E.C. had to adopt measures for their constant correction. Months ago I definitely repudiated this motion. It unfairly stated my position. At that time the C.E.C. was committed to the third party alliance which tacitly if not actually, accepted the proposition that LaFollette would be the candidate of the third party. Any denial of this is sheer hypocrisy. The motion I made proposed in effect that if at the coming conference the question of nominations was forced upon the conference and the choice lay between Ford (who was then in the field as a progressive candidate) and LaFollette, that if it had to the Workers Party would support the latter as the lesser of two evils. This was bad enough, but it indicates merely the opportunistic tangle we got into as a result of comrade Pepper’s beloved third party alliance.

Comrade Ruthenberg’s manufactured indignation that we should tolerate the nomination of LaFollette comes with ill grace, especially after his militant support of the third party alliance. Time and again he gave Mahoney, of the Minnesota farmer-labor party, to understand that if the Workers Party made any opposition to the candidacy of LaFollette in the approaching conferences and convention it would be purely formal, to keep the record clear. It is interesting to note also that when I introduced a motion in the C.E.C. at St. Paul which would have precipitated a break with the LaFollette forces then and there, it was lost by one vote, the vote of comrade Ruthenberg. His “fight” against LaFollette’s nomination was a fake. This was clearly shown by the following motion, introduced by comrade Ruthenberg and defeated by the C.E.C. on May 2, 1924:

“We shall nominate in the convention a candidate in opposition to LaFollette and cast our vote for such a candidate. We must, however, be careful to see to it that this manouvre does not defeat LaFollette, for to nominate another candidate and permit LaFollette to become the candidate of the July 4 convention in opposition to our nominee would be to destroy the class farmer-labor party as a mass organization.”

The Lesson to be Drawn

As I stated in the opening of this article, our labor party campaign has been waged under very serious difficulties, due to the lack of a more vigorous and definite movement for a party of industrial workers and poor farmers. Consequently, mistakes have been made, many of them verging into opportunism. But there is a fundamental difference in the way the present C.E.C. and the minority have reached to these mistakes. The C.E.C. majority went along with the third party alliance, but now frankly admits in their thesis that this was a mistake. They also recognize such opportunism as developed at St. Paul. More than that, they saw the opportunistic danger in making the election campaign under the banner of the skeleton national farmer-labor party, so they promptly cut loose from it and launched the Workers Party ticket. Likewise, now the C.E.C. perceives the opportunistic menace in continuing the use of the farmer-labor party slogan when there is no mass sentiment behind it, so they would avoid this disaster by dropping the farmer-labor party slogan.

But the minority are unregenerate in their opportunism. They have initiated and supported every opportunistic development in the labor party policy. They still support the Chicago split and the August thesis. They did not, in their thesis, admit that the third party alliance was a mistake. They supported fully such opportunistic tendencies as developed at the St. Paul convention. Nor did they justify our election policy of the W.P. running candidates in its own name. Comrade Lovestone was willing to see the Workers Party sacrifice this, its first opportunity to come before the workers nationally in an election campaign, in order that the beloved “class” farmer-labor party might be furthered, and they still try to minimize the results of the election campaign, of which every Communist should be proud. The minority now, in the face of the hostile decision of the Comintern, propose in their thesis that the W.P. follow a policy of penetrating the LaFollette movement. Their advocacy of the dead farmer-labor party slogan is calculated to plunge the Workers Party head over heels into the swamp of opportunism.

The meaning of this continued and unrelenting opportunism of the minority is quite clear. The majority has made mistakes. It admits them and corrects them. The minority admits nothing, corrects nothing. These farmer-labor Communists represent the real right-wing of the Workers Party. They are disappointed with the progress made so far by our party. They want quick results, and they are not particular as to what kind of results they get. Their plan is not to carry out the united front principles of the Comintern, but to establish a substitute opportunistic party in place of the Workers Party. The membership must repudiate this dangerous right-wing, liquidating tendency. The way to do it is to defeat overwhelmingly the thesis of the farmer-labor party Communists.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v02a-n233-supplement-dec-20-1924-DW-LOC.pdf