An expansive, ambitious speech on the problems, and possibilities, in remodeling Soviet society delivered by Bukharin at the apex of his authority during 1928’s commemoration of Lenin’s death. Transcribed here for the first time.

‘Leninism and the Problem of Cultural Revolution’ by Nikolai Bukharin from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 8 Nos. 7, 8 & 9. February 9, 16, & 23, 1928.

Comrades, on this solemn occasion I should like to choose as a fit matter for expatiation the subject of Leninism and the Problem of Cultural Revolution.

This subject is at present one of the most vital matters with which the Soviet Union and our Party are faced. It will be the greatest honour we can render our great master if, on this day of remembrance, we return again and again to him, to derive new strength from the teaching he has left us. For Our task is the “new formation of the world”, as theoretically formulated by Marx the great founder of scientific Communism. It is up to us to overcome quite extraordinary difficulties and to live and fight amidst capitalist encirclement. Capitalism is an enemy that has declared war to the knife on us.

Our opponents are strong, armed to the teeth, and continually increasing their armaments. Bourgeois-capitalist science and technics and the organisation of capitalist work are at present on the increase. Standardised and serial production, electrification, and a whole number of the latest technical innovations, the liquefaction of coal, the improved production and distribution of gas, the production of artificial fibres, which occupies an ever greater place in capitalist production and can at a moment’s notice be turned into the production of explosives; finally, the important military inventions, such as the dirigible motors on the land, on and under the water, and in the air all these things represent an elaborate technical preparation on the part of capitalism, with the help of which capitalism intends to maintain its position. The war and post- war crises have inflicted serious wounds on capitalism. The post-war crisis has not yet been overcome; on the horizon we see the indications of further catastrophes.

But in the meantime our opponents, undeterred by the fact that the crisis is not yet over, are fortifying the chief vantage-points of their position. We must deliberately face the fact that we are approaching a period of competition with these still powerful imperialist opponents. Of that fact we must not lose sight for a single minute, not for a single second. We are still destined to live for a long time under the shadow of the imperialist swords drawn against us. We have still the prospect of a long struggle with the “Holy Alliance” of the bourgeois counter-revolution, which will not and cannot leave us in peace, seeing that our peace and our growth, our work and our development all disturb the “peace” of the imperialist States. It is for this reason that our development and the tasks we have to solve within the country are so closely and indissolubly connected with the questions of international politics.

Our opponents fight us with all imaginable means. They also fight us on the ideologic front, where one of their chief weapons is that of speculation in regard to our technical and economic backwardness, our lack of culture, and the penury we have not yet succeeded in overcoming. The imperialist leaders and their adherents, all the enemies of a rising Socialism, all those that hate the iron dictatorship of the proletariat, all the Social Democratic cynics, all the petty-bourgeois sceptics, gnawed by doubts and prophecying destruction all of these are speculating on our backwardness.

On the one wing there are the powerful leaders of international capitalism, on the other their adherents all our manifold “friends” who have not infrequently derived their weapons from the arsenal of the open opponents of Socialism. It may often be observed how some cunning business-man and ideologist declares with assumed pathos that Bolshevism is the “great plague”, the terrible Asiatic illness threatening to invade Europe. With failing voices these whiners complain that Bolshevism represents the “destruction of all culture and civilisation”. Some of the particularly obstinate, refractory, and hypocritical imperialist spokesmen, especially such as once governed “public opinion” in imperial Russia, surpass all limits of bestial rage and even go so far as to designate the Soviet Union as the embodiment of Anti-Christ, as a “Satanocracy”, as Berdayev, the bard of the aristocrats, is pleased to call it in his counter-revolutionary rage.

Our Social Democratic opponents, again, show a zeal worthy of a better cause in spreading abroad malignant inventions, describing Russia as a semi-Asiatic country, at all times accustomed to an Eastern form of despotism, a country in which a dictatorship has been established which as closely resembles that of Horthy or Mussolini as one egg resembles another. (To this I may remark in parentheses that if the adherents of Trotzky designate us as Fascists, they have obviously borrowed this poisoned weapon from their Social Democratic friends.) All Social Democrats declare that we Communists have undertaken the realisation of a Utopian fancy, the construction of Socialism, a task calling for a higher cultural standard, for which reason our “enterprise” is doomed in advance and irrevocably to failure, however much we may preen ourselves and whatever excellent slogans we may invent. In the great Book of Destiny our failure, they affirm, is already registered, seeing that we are proceeding contrary to the iron laws of history. And the oppositional fragments which broke away from our Party, are following this same path in affirming that, if we are not saved by an immediate outbreak of the world revolution, our destruction is practically settled. All these people, therefore, produce much the same melody, whatever chords they strike.

It is highly characteristic that the argument of backwardness and lack of culture is not only directed against us Bolshevists of the Soviet Union now that our revolution records one success after the other. It is highly characteristic that the same argument was raised a very long time ago by the opponents of the Communist labour movement in general, who criticised the purpose of Communism by “proving” that the class of the uncultured, the oppressed, the pariahs, who are only capable of destroying, of initiating a wild anarchy, and of throwing back society to the level almost of pre-historic times, could not be productive of any good. It is characteristic, too, that even the half-friends of the Communist movement have several times since the inception of Communism drawn back half afraid from those whom they themselves had often called upon as saviours from the sins of the present capitalist civilisation. Such a prominent man as the great poet Heine, whom Marx called his friend and who really was in the friendliest of personal relations with the founder of scientific Communism, wrote shortly before his death of the Communists and of Communism:

“Nay, I am rather a prey to the secret fear of the artist and scholar, who sees our entire modern civilisation, the dearly bought achievements of so many centuries, the fruits of the very noblest efforts, imperiled by a victory of Communism.”

In the following year, 1855, this friend of Marx’, the revolutionary poet of Germany and one of the most radical figures of German public life, wrote as follows on the same subject: “With fear and horror I think of the epoch when these sinister iconoclasts come into power. With their gnarled hands they will shatter all the marble statues of the goddess of beauty.”

It is interesting to note that such a prominent member of our public life as Valeri Briussov, who subsequently became a member of our Party, was engaged in 1904 and 1905 in writing an undeniably beautiful poem, which he called “The Approaching Huns”, and for which he chose as an epigram the words “Stamp out their Paradise, Attila”, Attila here personifying Communism and the Paradise being that of the bourgeoisie.

At that time Valeri Briussov greeted our Party in song, calling us the “approaching Huns”.

Such an attitude was characteristic not only of the petty- bourgeois Philistines, but also of the best thinkers of the bourgeois-capitalist world and even of those who thanks to their unusual personal gifts endeavoured to liberate themselves from the net of the bourgeois-capitalist ideology. Even those who had a premonition of something new and historically important in the Communist movement, which was destined with a “wave of flaming blood” to revive the “worn-out body” of bourgeois culture and civilisation, saw in the workers new “Huns” who would shatter everything to atoms and allow all the glorious creations of human genius to rot while sowing new fields with their “elementary” rye when once they had wiped all traces of the old pre-capitalist and capitalist culture from the face of the earth.

Since these lines were written much time has elapsed. Much water has flowed and not a little blood. But the iron tongue of history has told us many things, which are now doubted by no one, however little he may think.

We have seen that it is not the sinister Communist iconoclasts nor the Hunnish leaders of the Communist labour movement, but rather the very elegantly dressed and “brilliant” lieutenants and generals of the imperialist armies who, armed with all the achievements of this civilisation, are threatening and destroying civilisation and culture and all their achievements, accumulated in the course of centuries. The same thing applies to the yet better dressed and perfumed diplomats of the most Christian States with their lisping talk, their kid gloves, and their “noble” anxiety for God and culture, with their “honourable” considerations as to the best way of throttling Communism; the kings of banks and stock-exchanges with all their tender male and female lilies in Solomon-like simplicity; the scholars who exert their brains, their knowledge, and their talents in efforts to provide capitalism with the maddest weapons for the destruction of the material and spiritual assets of present-day civilisation; the servants of God, the artists, the writers, and the singers who in all tongues and by all possible means serve the cause of the destructive policy of imperialism./

Among splinters of steel, in poisonous gases, in vermin, human excrements, and blood, the “noble” culture of capitalism threatens to expire. Capitalism, indeed, is ready to devour its own culture. It is not we, the “sinister iconoclasts” (how this name suits us!) that are the bearers of this destruction, for we save all that is valuable in our culture. It is our capitalist opponents who menace everything. It is against them that every honest man who is capable of considering the great problems of the day, must arm himself.

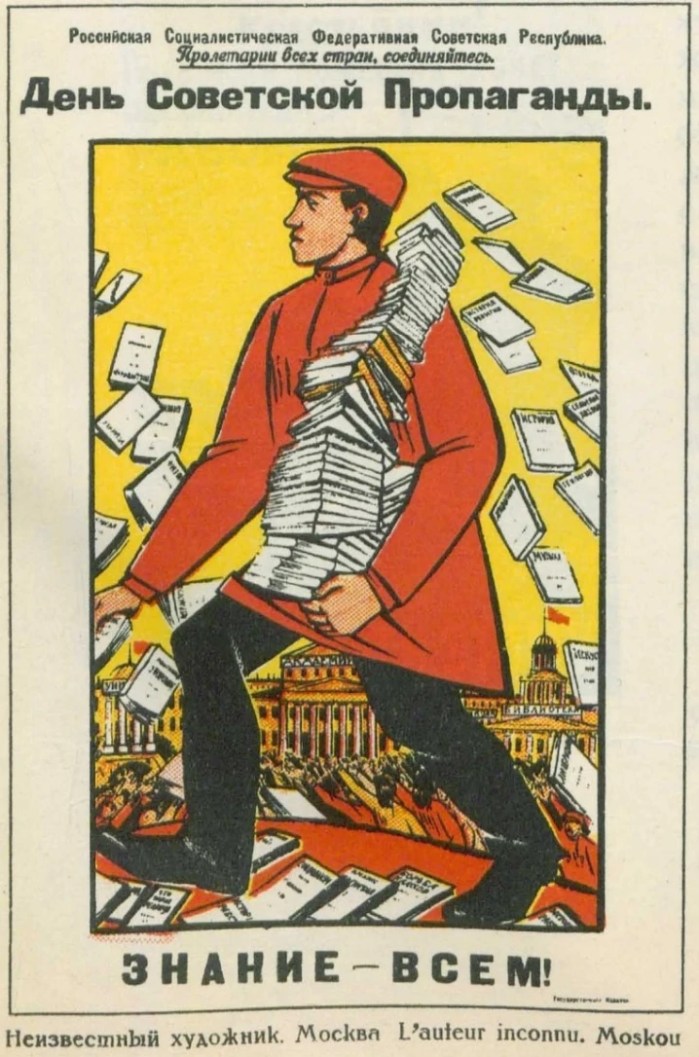

Something else has also become apparent. Our era has disclosed a further truth. It shows that after a period of temporary decay the “sinister Communist iconoclasts” are not only saving all that is worth saving from former times but are also outdoing all others in extending culture to an enormous mass of people, creating a tremendous cultural movement of the masses, tilling a vast area with the tractor of civilisation, and opening up not individual veins of culture whose brilliance disappears in the masses but rather a mighty stream of civilisation and cultural construction. And finally, a third truth has also been disclosed in the course of time. Enormous perspectives are now opened up to us for creative and constructive work, perspectives such as the capitalist world never knew and never could know. Economically, in our work among the masses, in our scientific and creative activity, and in regard to culture in general, we have already reached the threshold of tremendous tasks; we have left the narrow limits of a “chamber” culture and walk on the highroads and through the cities, sending our messengers of culture into the villages and into the remotest nooks and corners.

Our science is beginning to turn the propeller of practice faster and faster. It is now no longer a subject of occupation for individual “cabinet scholars”; it is already in immediate touch with the great tasks of economic construction, from which, directly or indirectly, it derives its theoretic programme. With febrile haste the working class is enlarging the scope of its work. It raises the oppressed and tormented nationalities to the level of historic life, aids them with a brotherly hand in developing their civilisation, and thus provides science with new tasks. It comprehends economic construction in a single tremendous organised system, uniting in a constantly increasing measure national economy in the State scheme and in the uniformity of systematic schemes. These tasks also confront science with very interesting problems, such as are fully unknown to the science of the bourgeois world. Finally, the working class pays the minutest attention to the problem of man himself, his work and his health, thus opening up new realms of science with new tasks and bringing theory and practice, science and life into closer contact along new lines.

Thus the mechanics of the workers’ dictatorship include culture more and more in the general circle of life of the masses, subjecting an increasingly ample science to the new requirements of life and adapting its development to the advance of the entire tremendous historical process. All this is very different from the sinister prophecies in which even the best thinkers of the bourgeois and capitalist world indulged, very different from the miserable lamentations, interspersed with malicious sallies, to be heard from the Social Democratic “critics” who bark themselves hoarse at the proletarian dictatorship. True, during the period of revolutionary warfare many “lilies’ were broken. But during the imperialist wars yet far more “lilies” were mowed down and far more nightingales were silenced by the roar of cannon. The important point is that if we compare the destruction caused by capitalism itself with the destructive side of the revolutionary process, we can declare without any pricks of conscience that it has cost us less to achieve a state of affairs which will definitely eliminate the destructive efforts of the perfumed and manicured barbarians of capitalist civilisation.

From the standpoint of cultural activity, the working class and its Party has placed the masses in the foreground. No more single prodigies, no more exotic hot-house creations; in the focus of our cultural work are the masses themselves. And it is with them that the point of gravity lies.

How ridiculously petty and contemptible are the accusations directed against victorious Communism. No other than Lenin, that passionate revolutionary, the great destroyer, the leader of the working class, who led the attack on the capitalist castles, fortresses, and estates, most emphatically and in his very last articles placed the cultural problem in the very centre of our Party and Soviet work. Very aptly Lenin declared that after the conquest and consolidation of the workers’ dictatorship our attitude towards Socialism had fundamentally changed. He wrote:

“This fundamental change consists in the fact that we formerly attached the main importance to the political fight, the revolution, the conquest of power. Now the main interest must centre on the peaceful and organisational “cultural” work. I may say that the point of gravitation has shifted to the side of cultural work, naturally apart from international relations in which regard the main importance attaches to defending our international position. But apart from this and considering only our internal economic conditions, our work must centre in cultural activity.”

This idea must be comprehensible to every member of our Party and to every worker who is desirous of becoming thoroughly conversant with the aims of his class and its historical development. In sketching the fundamental outlines, Marx also recorded this idea. The period of the workers’ dictatorship, the transition from the capitalist to the Socialist, and thence to the Communist, order of society, can be regarded from a particular standpoint, viz. that of a transformation in the entire predominant class, the working class. In fact, we can regard the process of proletarian dictatorship from the standpoint of a strengthening of proletarian authority; we can regard it from the standpoint of the development of the economic basis of Socialism, i.e. from the standpoint of the growth of our Socialist industry and transport, from the point of view of what we call the proletarian “key positions” or “heights of command”, or else we can consider it as the “socialised section” of our economy.

But it is also possible to regard this process from the standpoint of the changes entailed in the nature of the working class. In other words, this enormous historical process may be considered from the standpoint of a remodelling of the masses, the reformation of their nature, and in particular the re-forming of the proletariat. As is well known, Marx once wrote that in the great civil wars and in the struggles among the nations which occupied the stormy period separating capitalist society from Communism, the working class changed its own nature. Lenin, who never departed one jot from the Marxian teaching but only developed and intensified it, regarded this problem of a “remodelling of the masses” as the most significant, most difficult, and most essential problem confronting our Party.

And how did Lenin divide up this question when he set about analysing the conception of “cultural revolution?”

“We are faced with two great tasks. The first is the task to re-form our apparatus, which is worth practically nothing and which we have taken over wholesale from former times, for during the years of struggle we did not and could not succeed in creating any serious innovations in this direction. The second task consists in cultural work among the peasants, which forms the actual object of co-operation. If we had already realised perfect co-operation, we should now be standing with both feet on the basis of Socialism. But the presumption of such co-operation embodies such a high cultural level on the part of the peasantry (considering the peasantry as a mass), that it appears to be quite impossible without the aid of a cultural revolution.”

If we read these lines again and again, we are involuntarily prompted to ask “And how about the working class?” Throughout an entire epoch, for this in the word Lenin employs, two tasks are to occupy our attention, the reformation of the State apparatus and the hundred per cent. co-operation of the peasantry. To a superficial critic desirous of finding signs of “national limitations” and a “deviation in the direction of the peasantry”, it would be easy to designate these tasks, set up as the main objects of an entire epoch, as expressive of some sort of “deviation”.

In reality, however, the matter is altogether different. If Comrade Lenin speaks of the re-formation of our State apparatus, he naturally understands this to be in close alliance with the cultural rise of the working class. For what is meant by the “State apparatus” in the Soviet Union? The framework of State authority. And in what does State authority consist in our country? In the words of Marx, it is the working class which is “constituted as the State authority”. Our State is the most comprehensive organisation of the working class. Consequently the remodelling of the State apparatus, which Comrade Lenin set up as one of our two primary tasks, constitutes the most essential portion of our work among the working class. But in what direction must we remodel our State apparatus? Along the lines of a struggle against bureaucracy, the education of the working masses, the instruction of the working masses in the art of administration. The remodelling of the State apparatus is in the first line a cultural problem. In discussing the Party programme on the occasion of the VIII. Party Congress, Comrade Lenin spoke as follows:

“We know very well how this lack of culture weighs upon the Soviet authority and aids the rebirth of bureaucracy. According to the letter of the law, the Soviet authority is accessible to every worker; in reality, however, it is far from being at the command of all. And here it is not because the law intervenes, as was the case with bourgeois authority; on the contrary, our laws help to make authority accessible to all workers. But the laws alone can effect little. What we need is a mass of educational work, a thing that cannot be obtained quickly by means of a law, requiring rather a tremendous amount of work.”

In a cultural sense, the working class “matures” very slowly; it does not mature spasmodically nor yet uniformly in all its branches; it matures only, partially. Not all workers pass through the various workers’ faculties and high-schools; not all workers become “red managers” or Soviet officials; not all are equally connected with the organs of Soviet authority. But though it advances “particularly”, the working class does advance from one grade to another. When the predominant mass of the working class is firmly established at the tillers of the administration, bureaucracy and bureaucratism will die a natural death. The improvement of the cultural level of the workers is therefore a presumption for the actual improvement of our State apparatus.

And thus the entire gigantic programme of Lenin, as outlined in the said article in rapid but emphatic strokes, is divided into two tremendous tasks, firstly the co-operation of the peasants, to effect which an entire cultural revolution is necessary, and secondly the re-formation of our State apparatus and the penetration and replenishment of all its pores with culturally improved workers. This alliance between a peasantry, co-operating to one hundred per cent., and a State apparatus purged of all bureaucratic evils, really constitutes the great organisational and cultural task of our epoch.

I repeat that for Lenin it was the mass that stood in the centre of the entire system. Many years ago there was, both within and around the Party, a great discussion in regard to the cultural tasks. Lenin then pitted all his energy, all his revolutionary passion, and the heavy artillery of his overwhelming logic against the errors apparent in our ranks. After the events of October, there were many who desired to storm the very heavens; they excited themselves unduly in debating the questions of proletarian culture and in preparing the immediate revolution of all spheres of science and technics; there were some who thought that proletarian culture was a thing to be manufactured in experimental laboratories.

Lenin attacked such a conception with all the arguments at his disposal, and why he did so is quite obvious at present. He acted most strategically. He was right in fearing that these enthusiasts would probably get entangled in artificially cultivated theories and would thus turn away from the immeasurably more numerous and more elementary, but also more essential, cultural requirements of the masses. He therefore attacked the “twaddle” and “bombast” in regard to proletarian culture with bold references to such phenomena as corruption, Communist vainglory, and illiteracy. There lies the enemy, he said, that is what we must fight against with all our might; like that we shall attain results. But if we shut ourselves off, if we separate the working class from the masses or segregate part of the working class from the rest, or remove any small group of the proletariat from its social foundations, we shall be committing a tremendous and unforgivable error. It is not a question of upsetting all science at a blow, but rather of singling out the fundamental enemies of culture and education and destroying them as speedily as possible. These tasks must be given precedence, on them we must concentrate the entire attention of our Party, and against these evils we must fight most inexorably.

In connection with this Lenin set up a further task, that of taking from capitalism as much as was possible. It was impossible, he said, to transfer the focus of the revolution to the realm of mathematics, biology, and physics, without first solving at least a certain small percentage of the elementary and preliminary task which cried to the heavens for settlement and which, if neglected, would trip us up and be our ultimate ruin. It was therefore that Lenin so persistently advised us to take from capitalism all that could possibly be taken from it. At a meeting at Petrograd in March 1919, Lenin said:

“The masses have destroyed capitalism, but a mere destruction of capitalism will not help them. They must seize the culture that capitalism has left over for the purpose of building up Socialism; they must take all the science, technics, knowledge, and art, without which it is impossible to construct our Socialist life and society. But this science, this knowledge, and this art are in the hands and the heads of the specialists.”

I may here remind you of the fact that at that time a great portion of the workers, among them numerous members of our Party, failed to understand this necessity, and it was only the iron will and the logic of Lenin that could prevent the proper revolutionary policy from being consumed by “Left phrases” and could ultimately lead forth the proletariat from the complicated labyrinth of dangers onto the only right straight path of historical evolution.

It would, however, be altogether wrong to represent the matter as though Lenin had merely considered it necessary to take over the culture of the bourgeoisie in its entirety and without restrictions. That was by no means what he intended. He repeatedly told us that we must take over all such things as are useful to the proletariat, while energetically rejecting all that is harmful. His attitude towards religion, towards a philosophical idealism, towards the bourgeois sociology, and towards many other subjects is sufficiently well known. He more than once attacked those whose thoughts were completely dominated by bourgeois traditions. In particular I may call to mind his remarks. to the effect that in the realm of art we harbour many renegades from the bourgeois world, who offer us works without rhyme or reason under the pretence of proletarian art. But as a born strategist, Lenin knew how to distribute the forces at his disposal according to the importance of this or that sector of the cultural front.

And it is just this which is one of the most important presumptions for a correct policy in general and a proper cultural policy in particular. For, as Lenin put it, our peaceful, organisational, and cultural work is by no means in itself a “peaceful” activity, but only another form of the class struggle of the proletariat, of the fight for Socialism. Even when Lenin told us that we must “build up Socialism with the hands of our enemies” or maintained that “a good bourgeois specialist is better than ten bad Communists”, he was speaking of nothing else than this very class struggle, to be carried on by special methods.

It is now a long time since Lenin wrote his last article. Year by year we see more and more clearly that for each case that arises there are ever fewer “cut and dry” recipes to be found in Lenin. But then Leninism does not consist of “cut and dry” recipes. Lenin told us to study that which is, in its entire concreteness and with all its peculiarities. Lenin was far from desiring to apply to any given time measures and solutions employed three or four years before. And if we wish to proceed in the spirit of Lenin, we must render ourselves an account of all changes that have occurred since that time and take into consideration what tasks have already been fulfilled and what tasks are yet before us, how these tasks have been influenced by recent events, what completely new problems have arisen, and so on. It is only thus that Lenin’s disciples should consider questions.

In the article from which I have already quoted, Lenin writes as follows in regard to the co-operatives:

“This cultural revolution is all we now need to become a fully socialist country. But such a cultural revolution requires tremendous efforts both of a purely cultural nature (in view of our illiteracy) and in a material direction, since our development into a country of culture necessitates a certain material basis, an improvement of the material means of production.”

Do these principles still apply? Naturally they do. But nevertheless there have been some quantitative changes since that time. We are not now suffering starvation, and in spite of great material difficulties we have succeeded in raising our economy and our State budget to an appreciably higher level. What was at that time no more than a pious wish (viz., the increase of material means for cultural purpose), has not only become a necessity but in a certain sense it has become such a vital necessity, that it absolutely has to be satisfied, even at the cost of sacrifices on other fronts. If in one of his speeches Lenin maintained that we should not stint in cultural work, this must now be repeated with far stronger emphasis, seeing that a great many questions of economic development stand and fall with the problem of culture. Thus you will certainly all be aware that in our great constructional work there are a number of serious shortcomings, such as mathematical mistakes, negligence, faulty projects, and the like. This is ultimately a question of culture, and even the quantity of our output is adversely influenced by the fact that we do not always make sufficient use of West-European and American experiences. How often we set out to discover things that have been discovered long ago. We have not even learnt to reckon properly, although we really need to know that even better than the capitalists, seeing that our economy is on a much larger scale. We spend too much on our constructions, both because our materials are too expensive and because we employ antiquated and expensive technical methods when there is no objective reason why we should not be using more up-to-date systems.

But this is only one out of many aspects of this question. Does not rationalisation absolutely depend on the question of a higher cultural standard of our workers, our employees, our engineers, and our administrative officials? Is the bad working of our apparatus in the rural districts not an outcome of such shortcomings? Could we not have increased the rate of our savings if the broad masses had stood on a higher cultural level? Should we not be able to cope more successfully with bureaucracy, which is not only a social evil but also an impediment for the development of the productive powers of our economy? In a word, our production suffers by reason of our lack of culture. But, be this as it may, certain means are now at our disposal, which is a very great achievement. Just re- member the time when Lenin considered it a great success for us to have accumulated a sum of 20 millions. We have now a budget of 6000 millions. This shows the tremendous progress we have made with our Soviet economy.

Secondly, we have aroused and enhanced the activity of the people in the greatest degree, and that both of the proletariat and of the peasantry. We have also enhanced the cultural requirements of the masses. Our peasants and workers are no longer the peasants and workers of pre-revolutionary times. During the last four years we have observed a tremendous advance of culture in our peasantry and our working class. One of our comrades who works among the peasants and the village school teachers (Comrade Shatzky, now a member of the Party) told me that even in such a backward gubernia as Kaluga certain peasants possess libraries of 400 or 500 volumes. Moujiks may sometimes be heard discussing Tolstoy, Tourgeniev, etc. Was there ever anything of the kind prior to the coming of the Communist “Huns”?

We have so aroused the cultural requirements of the masses, that we now find it hard to pay the bill we have accepted. Thus it is fully comprehensible that our Party, the most active portion of the working class, and the more progressive among the peasants must make a great effort to satisfy the growing demands of the broad masses.

The culture of the masses has also been enhanced in regard to the most elementary things, such as the art of reading and writing. The level of the masses has risen because the horizon of the masses has expanded tremendously. In the direction of political enlightenment, the culture of the masses has attained an unprecedented level.

If we speak of our achievements, it seems to me that, without exaggeration, we can maintain that, as regards political consciousness and class consciousness, there is no proletariat in all the world to be compared with ours. We can also maintain that, as regards his political horizon, i.e. in regard to his conversance with the great questions of international politics, our peasant is practically the equal of the culturally and economically far more advanced peasant of Western Europe.

In regard to this realm of culture, we may well affirm that the great re-formation of the masses which ensued during the revolution, partly as an elementary phenomenon and partly as the result of the activity of the Red Army, our political work of enlightenment, and the entire mechanism of the proletarian dictatorship, has placed these masses politically at the head of the workers of the whole world.

A tremendous amount of work has been done among the working class and the peasantry. Very much has also been done among those nationalities which were formerly considered as foreign-born. This side of the problem must also by no means be neglected; it is of far greater importance than we generally suppose. We have also done much good educational work among the most backward sections of the working population, especially among the women. Without a dictatorship of the working class all this could never have been achieved. The stern language spoken by the dictatorship of the proletariat during the period of the civil war was the necessary presumption for this success.

We can therefore claim to have achieved great success in our work among the masses. But we have also to record some satisfactory results as regards the formation of our working cadres. We have acquired a great degree of organisational skill, we have learnt much that is new; we have enlarged our experience. Have we not established a considerable number of military cadres of our own? Yes, indeed we have. The commanding positions in the Red Army are to a great extent occupied not only by tried specialists, but also by qualified men risen from the “lower orders”. The framework keeping together the whole army already consists of our social material, of elements that have passed through the gigantic political mill, representatives of the proletarian dictatorship. We are already beginning to form special cadres of our own technicians. Such cadres we must establish all over the country. Throughout the country we have cadres of our fairly experienced administrators, men of the working class who have passed through the severe school of the civil war and the fight against starvation and misery. They are very tough fighters, men who in the fire of our revolution have not only steeled their “shoulders, heads, and hands”, but who have also acquired tremendous experience and a certain theoretic schooling. It is these men who hold the large and small levers of our tremendous mechanism, political and economic, Party and Soviet positions. With their administrative culture, their experience, their knowledge, their training, and their cultural requirements, they are now far above the very revolutionary but only slightly experienced men they were when they entered the period of civil war. Such more or less, is the present state of affairs in our cadres.

Of late we have commenced to deal with (and to solve) such problems as Lenin postponed indefinitely and as we were formerly really not in a position to approach. These are tasks which we may sum up under the head of the “scientific revolution”, in the sense of a revolution in the methods and system of science. A few years ago no such thing existed or could possibly exist, but now we are not only dealing with this task but are even partly solving it.

In a whole number of sciences, and that not only in the Social sciences in which Marxism has already for many years occupied a commanding position, but also in the natural sciences, a far-reaching re-formation is taking place. Marxism is carefully feeling its way. This is an extremely interesting phenomenon, which is unfortunately not accorded nearly enough attention in the press. We have already various prominent biologists who enthusiastically discuss Marxian dialectics and their application to biology. Physics, chemistry, and physiology are included in the same current, as are also reflexology, psychology, and pedagogics. There is even a society of mathematicians dealing with the problems of Marxism in relation to mathematics. All this shows that our cultural growth penetrates to the very highest realms of culture, and that Marxism, which fought originally with arms and with political propaganda, is now extending its work to the entire cultural front and is penetrating into every apartment of the cultural edifice, even into the “holy of holies” of former cultures, with a view to remodelling everything according to its own example.

The same process is also noticeable in art. I cannot devote myself here to enumerating all the new achievements recorded in this connection, but every unprejudiced hearer will admit that a “new direction”, with which we are associated has already made its appearance in literature. All of you will be aware that within the last twelvemonth there has been a decided transformation in our dramatic art. Such pieces as “The Revolt”, “The Armoured Train”, or “Lyubov Yarovaya” are by no means merely accidental.

It is obvious that all this is not without a tremendous practical significance. If art begins to speak more or less in our language without stuttering, lisping, or ogling to one side, it means that a number of people have been “infected” and have come to feel revolutionary. If the natural sciences not to speak of the social sciences are beginning to experience their revolution, means that they are the more speedily becoming weapons of the cultural and economic revolution itself. When extensive circles of pedagogues have come to do more than mere lip-service to our standpoint and champion it out of conviction, not formally but in reality, it means that the new generation succeeding us will advance more boldly and ripen to Socialism more rapidly.

Such are our achievements and successes and in regard to the remodelling of the masses, in regard to the remodelling and training of the cadres, in regard to the revolution in science and art. Have we thereby fulfilled our “historical” mission? Naturally not. We have merely the first steps behind us. We are still up to our ears in a sea of shortcomings and deficiencies. We have before us whole mountain ranges of the hardest and most passionate work. True, some of our “cultural” enemies,

blessed with all the benefits of the old world, predict our speedy decline by reason of what they call our “historical superfluity”. Thus, e.g., the famous professor Ustryalov is of opinion that we owe our victory to the fact of our far greater energy in comparison with the “Whites”. Nevertheless, the horoscope set us by Ustryalov envisages our certain decline. He writes as follows about us:

“Iron monsters, with metal hearts, machine-made souls, and cables in the place of nerves.

“What can our armed fronts do against them, against their terrible reflectors burning with condoned energy?

“They destroy the culture of decay, drench the earth with new energy, and, having fulfilled their mission, perish as the victims of complete self-absorption.”

Ustryalov probably foresaw how certain “grousers” were beginning to suffer from internal exhaustion and were thus even to be induced to attack our entire system. But such “microbes” have been removed to a more northern clime.

As regards our “self-absorption” and the “exhaustion” of our party, Ustryalov has indeed proved a very poor prophet. The party has “absorbed itself” so far that the working class reacted to the attempt of the “microbes” to penetrate into the pores of the party organism, by equipping an army of a hundred thousand fighters, who went straight from their workshops into the Communist ranks. And these “iron monsters” seem anything but inclined to succumb to the ravages of microbes, preferring to build and to fight with increased energy, in a full consciousness of their creative mission, leading the masses from victory to victory and overcoming, with really “animal” obstinacy the most discouraging difficulties they find in their path.

If we ask ourselves what we must do and what are the main tasks confronting us at present on this cultural sector of the battle-front, it seems to me that our answer must be as follows: in our cultural efforts we must even more speedily than in other respects overcome the period in which the “old” has already been destroyed without the “new” yet having been constructed. In our entire great revolution there is a certain amount of method, not only in an economic, but also in a political and cultural direction. At one time we overturned the old economic apparatus and destroyed it, when the old discipline of work went to pieces. We destroyed that old working discipline without immediately achieving a new one. We destroyed the old economic and administrative system, but did not immediately create a new system to take its place. The same was the case in a military connection in the army. We disintegrated the old army, which was a necessary step. After all, you cannot make an omelette without first breaking the eggs. And we did not immediately achieve the organisation of the Red Army.

The same may be said of the State apparatus. And this process is still in progress in a cultural respect. Thus we have destroyed the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois moral code and broken it to pieces; indeed, it crumbled under our very hands. But we cannot yet say that have set up any regulations of our own such as we require. There are many who look with contempt on the old morals (and they are right in doing so). but they have not yet any new standards and now hover in space without any points of gravitation. That is a very bad state of affairs which can do us great harm.

In regard to our manner of living and the standards regulating the relations of individuals to one another, in art, and in a number of other matters which impart what we may call “mental culture”, we have not yet got our bearings. In many of these connections there are not even the rudiments of any new standards. This often results in very regrettable consequences.

Relative instances from the different spheres of social life are known to all of you. The old family and sex morals are destroyed, and that thoroughly, but the influence of newly evolving standards of conduct in this regard is very weak, and the consequent interim entails many deplorable and very disadvantageous features of our manner of living. The old bureaucratic ideology has been destroyed, but there is still much to be desired in regard to the development of a new ideology of work for the workers, an attentive consideration for all “applicants”, especially if they are workers, the economical use of State funds, etc. We have shattered the old “ideal” of a subordinate devoted to his superior, but we cannot yet say that we have trained in any general sense such a type of the conscious public worker and fighter on all fronts of our activity, counted on to persecute all nepotism and toadyism. We are working in that direction, without as yet having more than the first few steps behind us.

The entire problem of rationalisation, and that not only of production but also of the manner of living, still faces us as a task to be fulfilled, or rather yet to be begun. We must pull ourselves together, whether it is a question of the masses, of the formation of cadres, or of the “highest” leaders. Not only have we not yet reached any result in this connection; in many respects we have not even laid our first foundations. To mention a few general tasks which confront us in this connection, we may formulate them somewhat as follows: We must make greater haste in getting over the intermediate stage between the eradication of the old and the introduction of the new. Starting from this standpoint, we must set ourselves a series of tasks, firstly as regards the masses, secondly in respect of the cadres, which represent the most progressive section of the masses, and finally with reference to the most highly qualified leading groups. In speaking of the masses, it is obvious that we are in the first place faced with the task of as rapid as possible an advance in the matter of elementary knowledge. It is an altogether mistaken policy to “scrap” certain reading rooms, libraries, and even schools, as is sometimes done in the rural districts. To “stint” in these things is altogether impermissible at the present time, for how can “civilised” members of co-operatives be trained without an increase in the system of educational establishments?

The care of the public health must also be extended as far as possible, the first step in this direction being a development of the fight against alcoholism and syphilis. It is only illiterate and really uncultured people that can ignore the importance of this task. I recently perused the work of Bumke, a German professor, which has also appeared in Russian. The writer cites a whole number of circumstances in proof of the fact that since the war it is particularly alcohol and syphilis which have diminished the capacity of the masses, a state of affairs particularly noticeable in this country. The fight against alcoholism and the organisation of really rational forms of amusement, the proper development of the cinema and wireless and the active encouragement of sport, are all matters we must take in hand without delay.

Furthermore, we must strive to make the broad masses conversant with a rationalisation of economy and with the art of reckoning accurately. These are assets required by the peasantry just as much as by the working class. Thus Comrade Shatzky visited a great number of farms and arrived at the undeniable conclusion that, in spite of the small budgets, nay, even within the limits of the present budgets, it should be possible to attain a greater agricultural output. A whole series of accurate investigations of peasant budgets led to calculations, which were distributed among the peasants by school-children and which caused great surprise among them. These calculations show very clearly that even within the limits of the ordinary budget of a peasant farm, there is the possibility of very considerable progress. Moreover, it would be advisable to consider a whole number of measures by which the peasant would be assisted not only in looking after his own farm but also in looking after the welfare of the entire district, or, in other words, of “public economy”. Finally, we must aim quite particularly at turning these districts into integral parts of what Lenin called the “Community State”.

The questions of the worker’s budget, of his family budget, of his participation in production, and of his increased interest in the course of production, and of a conscious and socialist-cultural attitude to this production are all matters of importance in our economy. We must also initiate the rationalisation of the manner of living. We must say that we are still most uncultivated, especially in view of the tasks which confront us. Sometimes we cannot stir a finger to put to right trifling matters on which much depends.

The question of amusements, of clubs, wireless, picture-theatres, the question of public baths, laundries, bakeries, schools, and libraries, and a number of other “every-day” questions, are not infrequently solved in such a way, that we set forth all sorts of fine plans, standpoints, and tasks, and yet permit a tremendous time to elapse before the work in question is executed. But Lenin said that our work of propaganda must consist in examples, in action, in energetic effectuation and not in a “political drumming”, which was once necessary but is now fairly out of date. There are very many facts to hand indicating that our efforts would profit greatly, if we were to substitute a good form of instruction for the present system of revisions and written reports. Real practical help would disappoint neither the peasant nor the worker, who would experience something really alive in the place of bureaucratic formalities. These are, more or less, the main tasks with which we are faced, so far as the masses are concerned.

These tasks, however, cannot be executed if our cadres are not improved to the utmost. A peasant summed up our shortcomings pretty tersely in saying, “You Communists are most of you very progressive people, but there are few of you that are willing really to put your shoulders to the wheel.” (Laughter.) That is very near the truth. Our “progress” consists in a great readiness to “project” all sorts of things. But there is as yet no control of execution, though Lenin repeatedly emphasised this side of the programme. And it is just the practical execution of the good resolutions passed which forms the best means of propaganda. Greater attention to the practical details of an economic and cultural nature in the rural districts and practical help even in quite small matters are better and more convincing means than whole cartloads of “political arguments”. This sort of propaganda and this sort of work must be given prime consideration.

But there are also a number of quite elementary “virtues” which are practically little known to our cadres and have to a very small extent become a part of our being. It can but be useful to call to mind the simple principles which Lenin set up as milestones of the work of construction, such principles as “Learn to reckon properly”, “Be thrifty”, and so on. In that respect we are still greatly behind-hand. If our cadres had really already acquired these indispensable qualities, it would surely not be possible for such miscalculations to occur as are frequently made. By no means. “Be accurate”. That is also quite an elementary rule. But can our cadres be said to have adopted this rule? Are they absolutely accurate in all things? Unfortunately not. To this very day we show traces of typically Russian negligence.

We must learn to adapt ourselves more quickly to circumstances, to go more into details, and to be altogether more thorough. We must cultivate in ourselves always and everywhere a feeling for the masses, a feeling of identity with the masses, a feeling of constant and unintermittent care for the masses, whether we are serving on the board of a trust, a syndicate, a trade union, a municipal Soviet, a gouberina committee, or a war committee. The feeling of responsibility must be constantly more developed. It not infrequently happens to us that, by reason of our lack of organisatory experience. it is not even known who is really responsible. The acquisition of such a feeling of responsibility, responsibility towards our class, our State, and ourselves, is also one of the cultural tasks incumbent upon us.

In certain sections of our Party there are tendencies towards resting in self-contentment on our laurels. We have, thank goodness, got the better of starvation. This bureaucratic self-contentment is a thing we must strike “hip and thigh”, for it savours of a psychology which is altogether incompatible with Bolshevism and Communism. It will not carry us very far. This proposition must be put most energetically to every worker and every soldier who is really devoted to the Party. As long as we live, there can be no “resting on oars” and no spiritual “laying on of fat”.

Besides this, we need an increase of special knowledge within our cadres. In this respect there are a number of weak points. Thus we have very few technicians with a medium degree of qualification, while many of our technical engineers are also insufficiently qualified. Technical and agricultural workers with a medium amount of qualification is what we mainly need. Very often such members of our Party as are unacquainted with a number of practical matters requiring special knowledge, are unable to fulfill their political functions in the Party. Now neither the peasants nor the workers can content themselves with such a political leadership as can talk about Chamberlain but have no idea of farming or technics. Our Party members not only give instructions but also see to the execution; they not only prescribe the “line” but also follow it up practically. They are not only “politicians” in general but also administrators.

If this is the case, the workers in these positions must necessarily extend their knowledge from year to year. In this connection, too, it is of importance that, outside the task of increasing our knowledge and training our feeling of responsibility towards the masses, special attention be paid to the small details. Let us make the following test. Let us take the “Life of the Worker” column and the respective correspondence columns of any of our bigger newspapers (“Ekonomitcheskaya Shisn”, “Trud”, “Gudok”, “Pravda”, “Rabotchaya Gazeta”, etc.), and read out all such remarks as refer to any shortcomings or misuses. Let us then try to analyse these various complaints. We shall soon see that nine tenths of all these different abuses do not result from “objective” circumstances, but could be avoided if dealt with energetically and in detail. If among the working masses there are still very considerable remnants of an indifferent attitude towards the interests of the State, there is on the other hand still an undeniable lack of culture in our administering cadres and even among members of the Party.

If we encounter instances of a negligent psychology among workers engaged immediately in production, we may also meet in the cadres with such as wish somehow or other “to get out of” performing their duties. (“We have been even worse off; somehow we shall, manage to get away with it”, is what we hear, or, again, “Things are not so very bad after all”.) This is a rotten psychology. Every leader, and in particular every Communist, must be an exemplary cultural pioneer, using all his energies to find out shortcomings and to correct them with energy. Even the smallest detail must not be regarded as a “trifle” lying outside our sphere of influence. There must be no such “trifles”, for it is of such details that life consists. They can even become political factors of importance. A sleepy “oblomov” attitude towards these small shortcomings is a nuisance we must combat with all our strength.

We must bring pressure to bear on all our functionaries immediately in touch with the masses, whether they are in the trade unions, or in the Soviet organs, or in the Party. He who attacks this question without “rolling up his shirt sleeves” is not a Communist. This indifference, this lack of attention to the immediate requirements of the masses, may easily grow into a disgusting form of bureaucracy and self-satisfaction on the part of the officials. That is a barbaric characteristic which we must attack with all the weapons at our command. We must tell all our workers that the mass cannot be educated or made to attain ever higher grades of active culture, if those in authority give an example of bureaucratic self-contentment and self-love. We must listen to every criticism on the part of the masses, instead of designating all censure as anti-Soviet, as malicious blockheads or bureaucratic idiots are inclined to do.

As regards the yet “higher” leading cadres, the following questions might well be raised. Greater intimacy with Western and American experiences, more thorough attention to our great economic and other plans and manoeuvres, elaboration of a number of scientific questions from special points of view, and periodical journeys through the length and breadth of the Soviet Union. We have frequently asserted that the revolutionary spirit in connection with efficiency, or again the revolutionary spirit in connection with Americanism are tasks confronting the Communists. What was meant by a revolutionary spirit? A revolutionary spirit means subordination and co-ordination of every single step in relation to the fundamental idea of revolution, i.e. to the idea of the world-revolution on the one hand and that of the construction of Socialism on the other. A revolutionary spirit, however, does not only presume such a mental and intellectual attitude; it also presumes a definite state of mind, a revolutionary enthusiasm and revolutionary optimism. A revolutionary spirit presumes a definite belief in a cause and in the denial of defeatism, pessimism, failure, and any kind of corruption, which is altogether incompatible with a revolutionary attitude.

A rising class can in no wise be in connection or sympathy with a rotten, pessimistic psychology. Naturally our optimism must not be confounded with a stupid optimism which declares everything in the world to be perfect. Voltaire created a hero of this stamp, a man who, in the face of an earthquake or a disagreeable illness, constantly declared that everything was very well arranged in the world. Nor can we assume the standpoint of St. Augustine who affirmed that God had only created evil things so as to make good things appear to better advantage. We must be steadfast in combating all signs of decline, decay, and dissolution, whether they appear in literature (as, e.g., in the writings of Yessenin), in politics, or in life. It is obvious that the rising class can only solve the tasks set it and complete its great work, if it is full of belief in its own powers and in the cause it has undertaken.

There have been very hard times in the history of our revolution, but our Party has managed to overcome them merely because it has been inexorable and has never under any circumstances lost its belief in its great cause. In this respect our leader Lenin was the model of the new type of men and fighters. Lenin revealed the new forms of our social existence. That fact is expressed in the slogan of world revolution, “All Power to the Soviets”. Lenin raised the veil concealing the future and showed us the example of a man who, in defiance of all obstacles and of even the most formidable of adverse circumstances, upheld the flag of revolution and marched forward on his way with a will of iron.

We can clearly see what tremendous historical perspectives are opened out before us. The world is already trembling with the distant rumble of the great revolution, which will surpass all that has ever been experienced or imagined. Gigantic masses will be put into motion and in our country the way will be opened up for further stupendous creative efforts. If we read the stupid references to “savage Huns” and if the “civilised hangmen” of the international bourgeoisie accuse us, the creators of a new life, of “barbarity”, we can answer with quiet consciences, “We are creating and shall continue to create a new civilisation, in comparison with which the civilisation of capitalism will appear like “caterwauling” compared with the heroic symphonies of Beethoven.”

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n07-feb-09-1928-Inprecor-op.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n08-feb-16-1928-Inprecor-op.pdf

PDF of issue 3: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n09-feb-23-1928-Inprecor-op.pdf