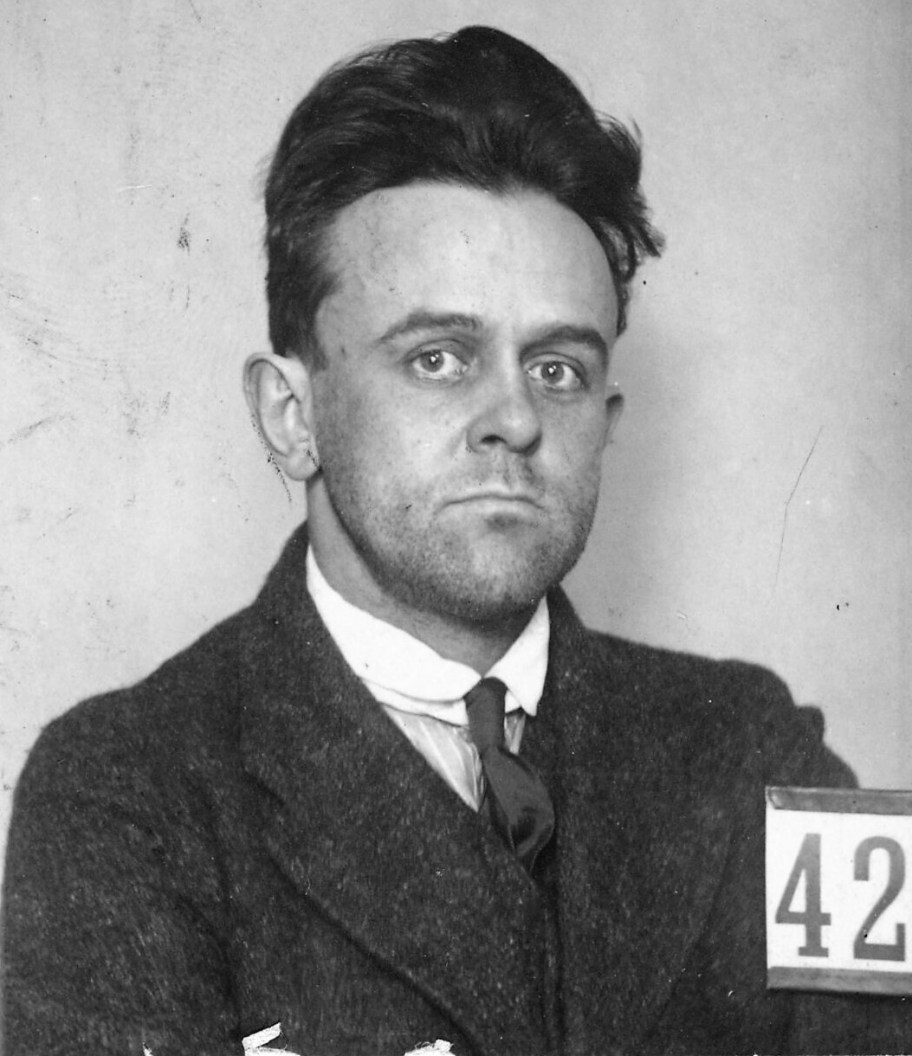

John Reed’s biographer, Granville Hicks, describes his travels, articles artistry, and growing political understanding and commitment as Reed became the leading journalist of his generation writing for Max Eastman’s still-admired magazine, The Masses.

‘John Reed and the Old Masses’ by Granville Hicks from New Masses. Vol. 18 No. 1. December 31, 1935.

During 1916, John Reed was engaged in many activities, not all of which were connected with the war. In abridging this chapter for magazine publication, it has been necessary to omit certain sections, such as that dealing with Reed’s poetry, and to condense others, such as those describing his meeting with Louise Bryant, the founding of the Provincetown Players and his operation. G.H.

AFTER his return from the Eastern Front, John Reed planned to visit his mother in Portland, but first he had to finish his articles for The Metropolitan. While he was staying in New York, in the latter weeks of November, 1915, he gave two lectures. The first was before the Harvard Club and many of his college acquaintances came to hear him. Reed, despite the successes he had had at Harvard, had been unpopular with many of the students and especially with the little group of aristocrats. Some of these men, having disliked Reed in college, came to his lecture prepared to scoff. They were skeptical of his stories, the tales of innumerable arrests, the flight from Constantinople, the sights of the battlefields. As he sensed the hostility of his listeners, he became arrogant, deliberately exaggerating the stories in order to shock these smug stay-at-homes. And afterwards, realizing that he had not been taken seriously, had not convinced anyone of the truth about the war, he was unhappy.

It was different when he went to speak to the prisoners at Sing Sing. Reed’s father had been a close friend of Thomas Mott Osborne, the warden, and Reed himself had followed with warm approval Osborne’s attempts at prison reform. He had dinner with the warden and with Spencer Miller and he fascinated them with his account of his adventures. When he was introduced to the audience in the crowded chapel, he began, with complete naturalness, “Hello, fellows,” and instantly there was applause. He talked a little about his own experiences in American and European jails and then went on to speak of the labor movement and the peace movement as phases of the struggle for freedom. He spoke exactly as if he were talking to a group of workers in a labor-union hall and there was no doubt that he felt more at home than he had at the Harvard Club. When he finished, there was cheering such as Osborne and Miller had seldom heard.

While he was in Portland, he met and fell in love with Louise Bryant, who joined him in New York soon after his return. Despite this new preoccupation and despite the fact that he was working very hard, for the demand for his articles and stories was strong, he found time for lecturing. At the Labor Forum he not only denounced Theodore Roosevelt and the other advocates of preparedness, but urged the workers to refuse to fight and said, in the course of the question period, that a civil war would be necessary to restore the government of the United States from the plutocracy to the people. At Columbia, speaking before the Social Study Club, he told the students that they need not expect the war to disgust men with fighting; on the contrary, it would foster the habit of killing.

Because he recognized the strength of the martial spirit, he found the emotional pacifism of many of his friends unrealistic and ineffectual and at the Intercollegiate Socialist Society he ventured the suggestion, to the horror of the pacifists, that the workers should arm. “A drilled nation,” he said, “in the power of the capitalist class is dangerous, but a drilled nation in the hands of the workers would be interesting. For instance, if the men employed in the munitions factories should take it into their heads to train a little now and then, if they should familiarize themselves with guns, isn’t there just a chance that their demands for better conditions would be listened to with somewhat more attention and respect?” He was beginning to feel that the question was not whether force should be used but who should use it.

Suddenly the Mexican issue re-emerged. On January 10, nineteen employes of an American mining company were shot in Mexico. Immediately the interventionists were clamoring at Washington. “California and Texas were part of Mexico once,” William Randolph Hearst wrote. “What has been done in California and Texas by the United States can be done all the way down to the southern bank of the Panama Canal and beyond. And if this country really wanted to do what would be for the best interests of civilization, the pacifying, prosperity-giving influence of the United States would be extended south to include both sides of the great canal.”

Reed gave an interview to Robert Mountsier, which was published in many papers throughout the country. He did not dwell on the moral issues but described the cost of intervention. “Every Mexican,” he said, “of whatever faction, will take up arms against the hated gringo. Even the women and children will join in the fighting.” He spoke of the courage of the Mexicans, their resourcefulness in guerilla warfare, the possibilities of tropical disease and the certainty of death for thousands of American soldiers.

Two months later came the attack of Villa’s men on Columbus, New Mexico, with the death of nine civilians and eight American troopers. While Pershing prepared to pursue Villa, Reed gave another interview and wrote a syndicated article. Once more he spoke of the dangers of intervention and this time he paid tribute as well to Villa’s personal qualities. He had been convinced, to his regret, that Villa was not the social idealist he had assumed, but he still admired him. “I don’t care if he is only a bandit,” he told John Kenneth Turner, after reading Turner’s analysis of Villa’s course of self-aggrandizement; “I like him just the same.” He thought a little of going to Mexico-to report Pershing’s expedition from Villa’s side.

IN the meantime he had an assignment from Collier’s to go to Florida to interview William Jennings Bryan. Much of what he saw on the way offended him. “The bloated silly people on this ridiculous private rich man’s train,” he wrote Louise Bryant, “throw pennies and dimes and quarters to be scrambled for by the Negroes whenever we stop at a station. Lord, how the white folks scream with laughter to see the coons fight each other, gouge each other’s eyes, get bleeding lips, scrambling over the money. Why don’t you suggest to Floyd Dell that some one draw a cartoon about it for The Masses? All the whites in this section look mean and cruel and vain. Have you ever seen Jim Crow cars, colored waiting rooms in stations, etc.? I have seen them before, so they don’t shock me so much as they did. Just make me feel sick. I hate the South.”

Reed joined Bryan at Palatka and the Great Commoner, remembering their previous meeting, welcomed him cordially and gave him a ticket to his lecture that night. The next morning they went together up The St. John River, with Bryan addressing the natives at each landing. In his private conversation, as in his public addresses, the former Secretary of State employed pompous platitudes and Reed took pleasure in drawing him out. He was opposed to war, but asked what he would do if his country were fighting for an unjust cause, he said that he could not answer hypothetical questions. He denounced trusts but praised capitalism: “Competition,” he said, “is absolutely necessary to commercial life, just as the air we breathe is necessary to physical life.”

He spoke eloquently about religion and Reed led him from religion to morality and from morality, by way of censorship, to art. When Reed said that he personally opposed censorship of any kind, Bryan declared in amazement, “Well, I never met anyone before who didn’t believe that decency should be preserved.” Reed went on to maintain that the human body was beautiful and Bryan crushingly remarked, “I suppose you would advocate people’s going naked on the street.” When Reed cheerfully said, “Why not?” Bryan frowned and announced, “We won’t discuss that subject anymore.”

In writing his account of the interview, Reed did not hesitate to emphasize Bryan’s fatuousness, but at the same time he paid tribute to his humanitarianism. “After all,” he wrote, “whatever is said, Bryan has always been on the side of democracy. Remember that he was talking popular government twenty years ago and getting called ‘anarchist’ for it; remember that he advocated such things as the income tax, the popular election of senators, railroad regulation, low tariff, the destruction of private monopoly and the initiative and referendum when such things were considered the dreams of an idiot; and remember that he is not yet done.” In recalling Bryan’s service to reform, Reed was making clear that, though he had little respect for the man, his criticisms were not to be identified with those of the reactionaries and war-mongers, who were trying in their ridicule of Bryan to discredit every effort to regulate private industry or preserve peace.

When Reed submitted his record of the interview, Bryan deleted most of the discussion of censorship on the ground that art was a field in which he had no expert knowledge. Otherwise he accepted Reed’s report as correct. In returning the notes, he wrote: “If you will pardon my personal interest in you, I will enclose an order on my publishers for The Prince of Peace. I feel that in maturer years you will give more consideration to the faith in which you were reared and which is a source of strength as well as a consolation to so many millions.”

IT was not difficult for Reed to secure magazine assignments such as the interview with Bryan, despite his reputation as a radical. In the spring of 1916, though the retreat from the new freedom was under way, a touch of radicalism was still something of an asset to a competent journalist. He was given an inkling of how wealth could be secured when a prominent industrialist with an eye on the presidency approached him and asked him to become his publicity manager. The industrialist had calculated the value of Reed’s following among the liberals and radicals as well as his skill as a journalist and he was willing to pay for both. It was an excellent chance to sell out and many of Reed’s Dutch Treat friends would have told him he was a fool to refuse.

The problem of integrity, however, was easy; Reed did not have to think twice before rejecting the steel magnate’s offer. But the whole problem of his future as a writer was complicated. Robert Rogers told him that, good as his journalism was, it only expressed a small part of his nature. It was time, Rogers said, for a novel or a long poem. Reed knew Rogers was right and he was constantly making notes and outlines for a novel, but he never got beyond the drafting of plans or the writing of a few tentative pages. There seemed to him to be something final about a novel and he was not ready for finality. Not only was the world changing too rapidly; he felt that, if he began a novel, he would be a different person when he finished it. If he marked time by continuing with articles and doing occasional short stories that were deliberate pot-boilers, it was because he felt that he was not ready to pour his whole nature into a sustained effort.

Throughout the spring of 1916, the idea persisted that it was not in the novel, not in poetry, that he could find expression, but in the drama. Writing Enter Dibble had been fun, but he was ready to admit that the future of the theater did not lie with such plays. What kept recurring to him was the possibility of building upon his experience with the Paterson pageant. He wanted to create a theater of the working class. Plans to give plays for the workers, though he was interested in these, were not enough. Hiram Moderwell, Leroy Scott and others had conceived a theater that would produce, at popular prices, plays that workers would want or ought to want to see. Reed had a bolder scheme: labor groups would dramatize the principal events in their lives, just as the Paterson workers had dramatized their strike. The idea grew: the best dramatizations from all over the country would be presented once a year, on May Day, in New York. Reed’s friends caught his enthusiasm and money for initial expenses was quickly raised, but he became absorbed in other things and the plan collapsed.

Busy as he was, he never neglected The Masses and when he had something that he really wanted to say, it was usually in The Masses that he said it. Nothing disturbed him more in the spring of 1916 than the growth of the preparedness movement. He watched with anger and alarm the founding of the National Security League, Wood’s and Roosevelt’s attempts to create a private army, the opening of the business men’s camp at Plattsburg and the spread of military training in the colleges. The news that Samuel Gompers had joined Howard Coffin, Ralph Easley and Hudson Maxim in working out details for industrial mobilization infuriated him. The preparedness parade, with its Wall Street sections, its thousands of bloodthirsty society women and its blatant banners, made him pound on the furniture and shout with disgust. This was something that had to be written about and he wrote about in The Masses.

Although “At the Throat of the Republic,” which appeared in the July issue, began with some colorful vituperation of the militarists, especially Theodore Roosevelt, it was for the most part straightforward exposition, handling facts with vicious precision. Reed showed that the National Security League was dominated by Hudson Maxim, president of the Maxim Munitions Corporation and that among its directors were representatives of United States Steel and Westinghouse Electric. He showed that the Navy League had as directors and officers J.P. Morgan, Edward Stotesbury of the Morgan interests and the Baldwin Locomotive Works, Robert Bacon and Henry Frick of United States Steel, George R. Sheldon of Bethlehem Steel and W.A. Clark, the copper king. He pointed out that The Metropolitan, in which Roosevelt advocated preparedness, was owned by Harry Payne Whitney, a Morgan man and a founder of the Navy League. He traced the various interlocking directorates of the Morgan and Rockefeller interests and showed that they dominated both the preparedness societies and the newly formed American International Corporation, organized for the exploitation of backward countries. He touched briefly on the conditions in the industries owned by these gentlemen in America and then he quoted Elihu Root: “The principles of American liberty stand in need of a renewed devotion on the part of the American people. We have forgotten. that in our vast material prosperity. We have grown so rich, we have lived in ease and comfort and peace so long, that we have forgotten to what we owe these agreeable instances of life.” Reed commented: “The workingman has not forgotten. He knows to whom he owes ‘these agreeable instances of life.’ He will do well to realize that his enemy is not Germany, nor Japan; his enemy is that two percent of the people of the United States who own sixty percent of the national wealth, that band of unscrupulous ‘patriots’ who have already robbed him of all he has, and are now planning to make a soldier out of him to defend their loot. We advocate that the workingman prepare himself against that enemy. That is our preparedness.”

REED wanted to write novels and poems, wanted to found a workers’ theater, wanted to write for The Masses, wanted to fight against war, wanted to get the most out of New York City for himself and for Louise Bryant. But there were two problems that he could not forget: money and health. Money meant primarily work for The Metropolitan and incidentally articles and stories for other paying magazines. It was an unpleasant problem, but not a very difficult one to solve; the magazines wanted what he wrote and it took a relatively small part of his energy to earn enough for his own needs and for the assistance of his mother. Health had become a more serious matter. His kidney periodically bothered him and his doctor was talking about an operation. In any case, the doctor said, he must have a rest and he and Louise Bryant went to Provincetown.

They arrived at the end of May and early in June he had to leave to attend the Republican, Democratic and Progressive conventions for The Metropolitan. In New York the doctors told Reed that he was better and he set out for Chicago. He saw Hughes nominated and witnessed the collapse of the Progressive convention. Then he went to Detroit for an interview with Henry Ford, with whom he spent part of two days. After observing the renomination of Wilson at St. Louis, he returned to Detroit, apparently to try to persuade Ford to finance a newspaper devoted to the cause of peace. The attempt failed, though for a little while Reed was swept off his feet by a great ambition and a great hope.

In the division of the fruits of the trip, The Masses once more got the better of The Metropolitan. “The National Circus,” which appeared in The Metropolitan for September, with cartoons by Art Young, was a perfunctory piece of reporting that conveyed little to the reader except the author’s boredom and his sense of the futility of the whole performance. But for The Masses Reed told the story of Roosevelt’s betrayal of the Progressives. He began by stating the case against Roosevelt and he stated it with some venom: “We were not fooled by the Colonel’s brand of patriotism. Neither were the munitions makers and the money trust; the Colonel was working for their benefit, so they backed him.” For the Colonel he had only contempt, but, remembering his father, he sympathized with the Progressives. They were not intelligent radicals, he knew; they were “common, ordinary, unenlightened people, the backwoods idealists.” But they were loyal to their ideals and they had an almost religious faith in Teddy. When he refused the nomination, they wandered around as if dazed and more than one of them wept. Although, like other Socialists, Reed had predicted that this would happen and had laughed at these men for their devotion to a person and to such a person as Theodore Roosevelt, he was moved. to admiration and sorrow.

But on the whole, Reed’s visit to Ford was more significant to him than anything that happened at the conventions. He liked Ford, the audacity with which he talked of millions of cars, the common sense with which he disposed of complicated problems, the streak of romanticism that had resulted in the Peace Ship. The efficient organization of production in the Ford plants overwhelmed Reed’s imagination. He had a vision of all this power in the hands of the workers and he convinced himself that the vision was shared by Henry Ford. Clutching at the fact that other industrialists and financiers criticized Ford, he made himself believe that here was a genuine revolutionary. The paternalism in Ford’s treatment of his employes irritated him, but he argued that it was only a phase in the creation of an industrial democracy. Ford was so powerful and seemed so benevolent and the working class was so docile, that for a brief period, Reed was ready to put his faith in a utopia created by kindly capitalists.

HIS enthusiasm did not survive the failure of his plan of interesting Ford in a newspaper, but that was less because he made a conscious effort to analyze Ford’s role in the capitalist system than because he had other things to think about. In particular, he had to make up his mind about Mexico. There was talk of enlarging the punitive expedition and John Wheeler of the Wheeler Syndicate wrote him, “It seems to me that this war will be a vehicle on which you would ride to a position in the literature of the country that would be above everybody else as a war correspondent.” Carl Hovey told him, “You have the chance to be the one correspondent in this war.” F.V. Ranck of The New York American wired: “Feel that you would be particularly effective. Wish you would decide to go. Don’t believe you will be able to keep out of it once things really begin to break. Can’t you give us definite answer?” But Reed steadily refused. He was tempted, of course, but there was the question of his health, the question of leaving Louise Bryant and especially the question of the kind of reporting that would be demanded of him. He strongly suspected that he would be required to glorify the American soldier in Mexico and that he could not do.

None of the newspaper executives could understand why he refused to go to either Europe or Mexico. His reputation was at its height. The Metropolitan Bulletin, a little paper sent to advertisers, published an article called “Insurgent Reed,” describing his independence and courage and calling him the best descriptive writer in the world. The publication of The War in Eastern Europe, though the book had a small sale, brought excellent reviews, not only in the liberal and radical weeklies but also in the daily press. Most of the reviewers, including John Dos Passos, who reviewed it for The Harvard Monthly, spoke of the picturesqueness of the book, its unpretentiousness and its humor. A few, notably Floyd Dell in The Masses, saw in it more than colorful reporting; they found an understanding of human beings that had significance for the student of international affairs. All agreed that John Reed was as able a war correspondent as any in America.

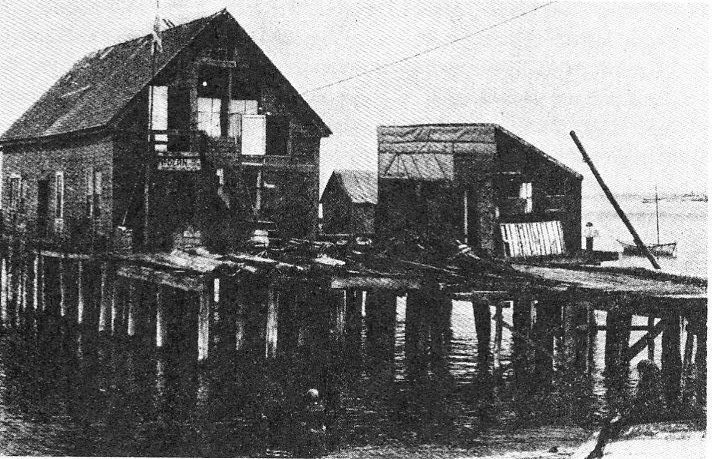

And John Reed, instead of going off to see General Pershing catch Pancho Villa, stayed in Provincetown. The summer before, George Cram Cook and Susan Glaspell had produced two groups of one-act plays and they were eager to attempt further experiments. Reed’s persistent interest in the theater flared into enthusiasm. Soon he was devoting as much time to the Provincetown Players as he was to his own writing. They took a shed on the end of a fishing wharf, cleaned it out and built a stage. The first bill consisted of Neith Boyce’s Winter Nights, Suppressed Desires, by Cook and Glaspell, which had been given the preceding summer and Reed’s Freedom. The theater was filled and Cook immediately started securing subscriptions for a summer season.

Freedom, which had been rejected by the Washington Square Players, was a good-humored satire of romanticism. It is a story of four prisoners, Poet, Romancer, Smith and Trusty. After years of plotting and working, the Poet and the Romancer are at last ready to escape. At first they persuade the Trusty to join them, but deciding that he has a place in prison and would have none outside, he chooses to stay. Then the Poet remembers that he has won his reputation as a prison poet and says, “For God’s sake, I’m free?” Romancer and Smith persist, but when Romancer discovers that the room has no bars and is on the ground floor, he declares that no man of honor would escape under such conditions. Smith says, “Well, the difference between you sapheads and me is that I want to get out and you just think you do. You’re playing a little game where the rules are more important than who wins. I’m willing to grant that you have it on me as far as honor and patriotism and reputation go, but all I want is freedom.” The others make so much noise in denouncing him as a coward and a traitor that the guards come. Romancer, Poet and Trusty unite in attacking Smith for attempting to escape and say that they tried to stop him. Smith has the last line: “There’s not a word of truth in it! I was trying to break into a padded cell so I could be free!”

Except insofar as it served to mark the distinction between Reed’s own kind of romanticism and the romantic poses of the pseudo-revolutionaries, the play was unimportant, though possibly it had as much significance as the others on the same bill. The only major dramatic talent, of course, that emerged that summer at Provincetown was Eugene O’Neill’s. Bound East for Cardiff was produced on the second bill, with Reed in the cast and a little later Louise Bryant appeared in Thirst. Reed acted in several plays, including The Game, a morality play written by Louise Bryant and staged by the Zorachs, who provided an abstract setting and introduced a stylized type of acting. He also wrote a one-act play, The Eternal Quadrangle, in which he and Louise Bryant and George Cram Cook took the leading parts. It was another Shavian farce, a burlesque of the “triangle” plays of Broadway with incidental comments on love and the institution of marriage. It was written in haste, to fit the needs of the Players and Reed did not seek either to publish it or to have it produced a second time.

The conviction grew in Reed that the Provincetown Players had importance for the theater and he was insistent, in the face of skepticism, that the experiment should be continued in New York. On September 5, a meeting was called, with Rogers in the chair and Reed, Cook and a few other enthusiasts won a majority of the members to their side. The next day a constitution was presented and adopted and plans were made for the first performances in the city.

Reed and Louise Bryant lingered on in Provincetown until the end of September. He was now negotiating with the editors of The Metropolitan with regard to a trip to China. Eager to have Reed in any land where there would be colorful scenes for him to describe, Whigham and Hovey ap- proved the suggestion. But there was the question of his health. He was feeling stronger after his summer by the ocean, but the infection of his kidney was not cured.

Reed found more and more difficulty in writing for The Metropolitan. The editors vetoed his suggestions, for they knew that the subjects he proposed, treated as he would treat them, would be dangerous. He tried his hand at short stories, but he had no real talent for pot-boilers. Increasingly it seemed to him that the trip to China offered the only possibility for continued work with the magazine.

After his return from Provincetown to New York, he did secure one assignment that pleased him. The New York Tribune sent him down to Bayonne to report the strike in the Standard Oil plants and he did an article for The Metropolitan as well. He described the strike as akin to those in the Colorado coal fields, the Michigan copper mines and the Youngstown steel works-a desperate, unorganized revolt of oppressed workers. His gift for sharp portrayal re- turned, now that he had a congenial theme, and he depicted the conditions of the immigrants, the Rockefeller domination of the city, the victimization of the workers by the tradesmen, the law and the church, the progress of the strike and the use of violence by the police and the company’s thugs. It was the last article Reed wrote for The Metropolitan and he showed once more that, when his sympathies were aroused, he had no superiors in journalism. The fact that his sympathies were always excited by the sufferings of workers meant that he was better as a labor-reporter than as a war correspondent, but capitalist journalism had little place for labor-reporters like Reed and the time was coming when there would be no place at all.

As the presidential election drew near, Reed came to feel that the only thing that mattered was to keep the United States out of the war and that the only hope of doing. so was to re-elect Woodrow Wilson. In the summer he had joined Albert Jay Nock, Lincoln Steffens, Boardman Robinson and others in addressing a letter to Hughes, questioning him about his views on Mexico, neutrality, trusts and the income tax. Now, together with Henrietta Rodman, Franklin Giddings, Carlton Hayes and John Dewey, he signed an appeal to Socialists, asking them to vote for Wilson. “Every protest vote is a luxury dearly bought,” the statement read. “Its price is the risk of losing much social justice already gained and blocking much. immediate progress.” He became a member of the group of writers that George Creel organized to support Wilson, a group that included Steffens, Fred Howe, Zona Gale, Hutchins Hapgood, George Cram Cook and Susan Glaspell. In a widely-syndicated article, one of a series by members of this group, he wrote: “I am for Wilson because, in the most difficult situation any American president since Lincoln has had to face, he has dared to stand for the rights of weak nations in refusing to invade Mexico; he has unflinchingly advocated the settlement of international disputes by peaceful means; he has opposed the doctrine of militarism and has warned the American people against sinister influences at work to plunge them into war; and in this dark day for liberalism. in the United States, he has declared himself a liberal and proved it by the nomination of Louis D. Brandeis and John H. Clarke to the supreme court, by forcing the enactment. of the Clayton bill, the child labor bill and the workmen’s compensation act and by the labor planks in the St. Louis platform.”

Reed went on to attack the Republicans, especially Roosevelt, “the arch-disciple of Professor Bernhardi, believer in war for its own sake, the leader of the munitions-makers’ party and a traitor to the people.” One may suppose that Reed supported Wilson chiefly in order to oppose the Republicans. Indeed, later, when he was a little ashamed of the position he had taken, he said, “I supported Wilson simply because Wall Street was against him.” It was ironical, of course, that, at the moment when Wilson was swiftly moving towards war, Reed should support him as a peace-maker, but he was only one of the millions who were deceived and betrayed. The fact that Benson, the Socialist candidate, deserted his party six months later to support the war, may have made Reed feel less guilty for having supported Wilson.

A week after the election, Reed entered Johns Hopkins hospital. Prolonged and painful examinations led to the conclusion that an operation was necessary and on November 22, 1916, his left kidney was removed.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v18n01-dec-31-1935-NM.pdf