Clara Zetkin’s oldest son, and Marxist activists in his own right, Maxim Zetkin reviews a posthumous collection of the letters of Victor Adler and Frederick Engels published in Austria in 1922. I am unaware of there ever being an English translation of the collection.

‘The Adler-Engels Correspondence’ by Maxim Zetkin from Communist International. New Vol. 1 No. 24. January, 1923.

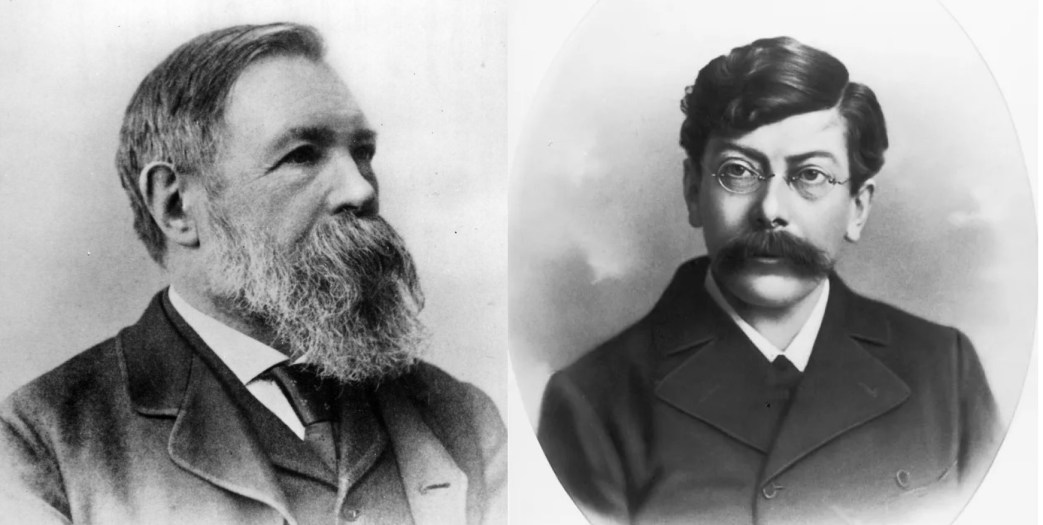

When we read the letters exchanged between Victor Adler and Frederick Engels published in this volume, the grand figures of these two noted leaders of the Labour movement seem to stand out as though they were alive. A chapter of the history of the Labour movement is revived. One sees again the unexpectedly rapid development, the surprisingly rapid success, of the Austrian Social-Democratic Party under Adler’s brilliant leadership, during the period of 1890-1895. (“Adler has organised the thing splendidly” this and similar references are frequently made by Engels.) The entire international movement of the proletariat passes in review before us. The World Congresses-the “International Guards Parades” as Engels once somewhat irreverently described them-the Congresses of Paris (1889), of Brussels (1891), of Zürich (1893), refreshing in our memories the glorious old times when the Second International was still in the ascendant. “The International is now established, and it is invincible,” says Adler after the Congress of Zürich. One after another arise the grand figures of nearly all those who have played any part in the movement during the years 1890-1895, or any part in politics in general. Liebknecht, Bebel, Kautsky, Zetkin, Guesde, Jaurès, Millerand, Turati, Bernstein, Keir Hardie, and so on.

We see before us the grand figures of Adler and Engels, who, even in their private lives, command respect and affection. Adler looks up to his older friend with confidence and adoration, and the latter is always ready to help with word and deed, never affecting the overbearing attitude of a schoolmaster. Adler, indeed, was at times in financial straits, and this fact could be appreciated only by those who knew that Adler had inherited considerable wealth from his family, which was sacrificed by him for the Party. Engels generously but unostentatiously helped Adler, and Adler accepted this aid as from a friend, without squeamishness, yet with full appreciation of the kindness that had been shown him. Thus Engels writes on May 19th, 1892: “I therefore think it necessary for the further development of the Austrian movement that you should be given the opportunity, first, of meeting all the unavoidable current expenses, and, secondly also, of making every possible provision for the future. I would therefore propose to put at your disposal the above-mentioned fees” (one thousand marks due to Engels from his publisher, Dietz, for “The Situation of the Working Class in England”).”

Adler replied: “Your offer is so friendly in substance, so exquisitely kind in form, and so honourable as regards the person who makes it, that I will tell you quite frankly that in the course of a fairly long period it has been the first ray of light which brought joy to my inner being.” It was at that time that Adler was beset by many cares, owing to the prolonged and severe illness of his wife.

Equally magnanimous was the attitude of Adler and Engels in the delicate matter of creating the proper atmosphere for Louise Kautsky (Karl Kautsky’s first wife). She should have everything that she needed, without being influenced or put in a false position. Many pages are devoted by both of them to the discussion of the pros and cons, in order to arrive at the proper decision, in a spirit of utter unselfishness. Adler writes: “The fact of Louise being with you relieves our mind. However, from her letter to Emma, I understand that she is still unsettled in her mind as to whether she should stay with you or not. I would desire it, but I will take care not to influence her.” Engels replied: “Best thanks for your hint as to Louise. It is also my wish that she should remain with me; if she decides to go, it will be very hard for me to part from her. But it would cause me constant pain if I were compelled to believe that she had sacrificed other duties. and other prospects for my sake.”

When Engels lay on his death-bed, seized with a severe cancer of the throat, and unsuspecting of his approaching end, Adler hastened to him, but was careful to conceal the true cause of his anxiety. He tried to make Engels believe that he was merely taking advantage of an unexpected vacation to visit his friend and take his advice upon difficult political questions. The letter in which he wrote of his coming was the last letter that Adler wrote to Engels; it was dated July 15th, 1895. On August 5th, 1895, Engels passed away; his mortal remains were cremated and his ashes thrown into the sea, in accordance with his expressed wish.

On the whole, the private life of the two correspondents is naturally given little prominence in these letters. First and foremost are the affairs of the Party, political and economic questions, sociology and history. The work of the Party brings its little and big worries, as well as its little and big joys. Many a sigh is heaved by Adler; and anyone who is not alien to Party life can well appreciate this. Adler writes: “The whole day long I have worked like a horse, and now I must immediately go to a workers’ meeting.” At that meeting the newspaper was to be established, the necessary funds collected, and the assistance of the necessary workers enlisted. We feel all these things as we read, and we appreciate the ready way in which Engels contributed his aid by word and deed. We share in the sad complaint made by Adler: “The worst of it is, not that we have an insufficiency of forces, but rather that we have a super-abundance of people for whom we have no use.” The daily work consumes the man entirely, without leaving any time for himself. Adler writes: “I thoroughly enjoy my imprisonment,” and he had enough opportunity for enjoying it. Thus, on June 15th, 1895, he writes from the Rudolfsheim County Gaol: “Dear General! In a few days I shall be released. Thanks to my determination to have this time for myself, and to cast away for a fortnight all things temporal, I have enjoyed the time spent here since May 18th more than any other period in the course of a great many years. I have found it so delightful and refreshing.” How characteristic is this utterance of the overworked Party man! Engels is, of course, less enthusiastic about Alder’s delightful arrest; he finds that the newspaper cannot spare him. Adler should devote his time to the newspaper: sitting in prison should be left to the “sitting editor,” or, as Engels aptly describes him, the lamb that has to bear all the sins of the editorial board. We find frequent and thorough-going discussions in these letters upon the situation in the various countries. We see Engels at work, giving his opinions, his advice and predictions, based on the fundamental investigation of economic and social relations in the respective country. One should read, for instance, the letter written by Engels on October 11th, 1893, dealing exhaustively with Austria. Unfortunately, the letter is too long to be quoted here in extenso, but a few remarks can be given. We thus find in Austria “strongly developed industry, but mostly still backward in regard to productive forces; the industrialists are kept in tow by the Stock Exchange. A politically fairly indifferent crowd of Philistines in the cities; the country farmers encumbered with debts and exploited by the landowners; the big proprietors in the saddle as the real rulers of the land, content with their political position, which indirectly makes their sway secure. A big bourgeoisie comprising a small number of high financiers, closely allied with the major industries, exercising their political power in even more indirect fashion and even more contented. On the other hand, the peasantry cannot be organised because it is broken up by small farming.” Engels goes on to describe the “Government which, in spite of appearances, is formally but little restricted in its autocratic appetites, constantly worried over the question of national minorities, over its perpetual financial difficulties, over the Hungarian question and foreign complications.” Engels arrives at the conclusion: “As against parties which never know what they want, and a Government which is equally ignorant. of its own mind, a party that is conscious of its own aims, and pursues them vigorously and perseveringly, must always win. Furthermore, everything that the Austrian Workers’ Party desires. and hopes to achieve is dictated by the very needs of the progressing economic development of the country.” This was the prophecy made by Engels before he learned that Tauffe had already officially announced the contemplated electoral reform in Austria.

The conditions of the working class in England at that time are depicted by Engels in an article contributed by him to the Arbeiter Zeitung, and dated May 23rd, 1890. He lays stress on the great importance of the then beginning organisation of the unskilled workers. “On April 1st, 1889, was founded the Gas-workers’ and General Labourers’ Union; it has 100,000 members today…Now (after the Dock Strike) union after union is being formed among these mostly unskilled workers (‘the bottom elements of the workers of East London’). Yet there is a wide difference between these new unions and the old trade unions. The old unions of the skilled workers are exclusive organisations. They debar from membership all workers who have not been apprenticed to the craft, thus creating for themselves the competition of a large body of unskilled; they are wealthy, but all their funds are devoted to sick and death benefits; they are conservative, and call themselves’ Socialists up to a certain point. On the other hand, the new unskilled unions will accept any skilled worker; they are substantially, and the gas workers exclusively, strike-unions, and their funds are strike-funds; and, if they are not yet Socialists to a man, they choose none but Socialists as their leaders.” Full credit is given to the work of Marx’s daughter, Eleanor Aveling, in the organisation of the unskilled, particularly of the women. On the whole, Engels depicted the situation in excessively roseate hues under the fresh impression of the successful May Day celebration of 1890, and in view of the rapid rise of the unions of the unskilled labourers. On March 16th, 1895, he writes somewhat more soberly: “The movement here may be summed up as follows: instinctive progress goes on amongst the masses, the tendency is maintained; but every time there is need to give conscious expression to this instinct and impulsive tendency, this is done by the sectarian leaders in such a stupid and narrow-minded manner that one would feel tempted to shower abuses at them. But this is precisely the Anglo-Saxon method, after all.”

Clear light on the blurred situation among the French ‘Socialists’ is thrown by Engels in a letter dated July 7th, 1894. Now, when history has already spoken, one reads with particular relish what Engels has to say about Millerand and Jaurès. He writes: “Of the principal leaders, Millerand is one of the shrewdest, and I believe also one of the most straightforward; but I fear that he is still possessed of some bourgeois-juridical prejudices, even stronger that he suspects it himself. Jaurès is a professor, a doctrinaire, who was fond of listening to his own voice, and to whom the Chamber listens more gladly than to either Guesde or Vaillant, because he is still akin to the gentlemen of the Majority. I believe he has the honest intention of developing into a real Socialist.”

In parenthesis, it should be observed that references to individual politicians in these letters are made only in connection with their work and the movement as a whole; seldom does one find a thorough-going characterisation; we get mostly brief and terse remarks. Thus, in speaking of Vollmar’s fiasco in his first revisionist attempts, Engels casually remarks: “This should suffice for an ex-soldier of the Pope.” And in March, 1895, Engels writes about Edward Bernstein’s articles on the third volume of Capital: “E. Bernstein’s articles are extremely confused.” Had Engels lived to know the latter-day Bernstein, he would certainly not have excused him because of his neurasthenia and overwork.

As is known, Marx and Engels devoted a good deal of attention to Russia. In these letters, however, there is little talk about Russia. It is only en passant that Engels writes, on December 22nd, 1894: “In Russia it is the beginning of the end of the Tsarist autocracy, for the autocracy will hardly withstand the latest shuffling of the throne.” In the same letter we read: In the German Empire ‘Little Willy’ wants to force the passage of the Haliez and destroy a great empire.” Germany and the German movement in these letters. A short reference to the policy of Herr von Köller” and “Little Willy,” a few stray remarks about Liebknecht, Bebel and a few others, a few words about traditional German narrowmindedness, and that is about all.

General questions are discussed as they arise in connection with the everyday tasks, e.g., the agitation upon the land question, the significance of the franchise, and so forth. Thus, Engels writes to the Party Conference at Vienna in March, 1894: “In Austria it is a question of winning universal suffrage, the weapon which in the hands of a class-conscious working class goes farther and hits harder than the small-calibre rifle in the hands of a drilled soldier.”

In this connection Engels sheds light also upon the international effect of political events: “It will be only after you (i.e., the Austrians) will have won electoral reform–of some kind–that there will be any sense in the agitation against the three-class electoral system in Prussia. And even now the fact that an electoral reform of any kind is to be granted in Austria will remove the menace to universal suffrage in Germany.

High value for the proletariat is put on parliament. Engels writes on October 11th, 1893: “Here it ought to be said: the advent of the first Social-Democrat into the Reichsrath has marked the dawn of a new epoch for Austria.”

The views of Engels on tactics can be seen from a passage in his letter of August 30th, 1892, which reads: “There are only too many who, for the sake of convenience and to avoid worrying their brains, would like to adopt for all eternity the tactics that are suitable for the moment. We do not make our tactics out of nothing, but out of the changing circumstances; in our present situation we must only too frequently let our opponents dictate our tactics.”

Particularly interesting is the attitude of Adler and Engels toward the General Strike. From their correspondence we learn what vagueness there existed at the time as to the possibilities of the General Strike. The comrades approach the General Strike as gingerly as a society dame handling a hand-grenade. Because of their importance, I am quoting more fully some passages in the letters. We read in Adler’s letter of October 11th, 1893: “I have managed to get the question of the General Strike put off, I hope, for a long time to come.” A few weeks later Adler writes: “The General Strike is naturally dead, even as a useful threat to the enemy; for even the elbow refuses to believe in it.” Engels writes, on January 11th, 1894: “The Czechs at the Budweis Party Conference have discarded the General Strike, which seemed to make most noise out there. Further on we read: It was inconceivable tactlessness (on the part of Karl Kautsky), in the midst of a movement fighting tooth and nail against the catchphrase of the General Strike, to try and launch a purely academic and abstract discussion of the pros and cons of the subject.” Adler writes again on March 19th, 1894: “The Party Conference (at Vienna) will no doubt instruct us to keep the General Strike, as a weapon, in our minds, but without forcing us to apply it. The most dangerous element, the miners, I hope to win over by a separate agreement, so that the intensification of their demand for the eight-hour shift shall not force us into a General Strike.” To this Engels replies, a few days later: “I congratulate you on the manner in which you have lulled the General Strike to sleep.” Finally, Adler writes again: “I am satisfied with the outcome of the Party Conference. The General Strike was recognised as the ‘last resort,’ which was a great relief to everybody, not only to myself.”

It is particularly important and interesting to read what Engels says about revolution, notably about the French Revolution (in his letter to Adler on December 4th, 1889). I can quote here only a few striking passages: “We will emphatically point out that the revolutionary heads of the great French Revolution properly saw the force that alone could save the Revolution. The Paris Commune (Cloots) was in favour of a campaign of propaganda as the only means of salvation…But the Commune, Hebert, Cloots, etc., was beheaded. The plebians, the embryonic elements of the later proletarians, whose energy alone could save the Revolution, were brought to reason and order.”

The influence of external political events upon the Revolution is clearly seen. “Danton sought peace with England, i.e., with Fox and the English Opposition. The English elections proved favourable to Pitt, and Fox was removed from office and power for many years to come. This was the undoing of Danton: Robespierre conquered and beheaded him.” Robespierre fared no better. The Reign of Terror reached the height of madness, because it was necessary to maintain Robespierre at the helm under the then prevailing internal circumstances. But it was rendered absolutely superfluous by the victory of Fleury on June 24th, 1794, who not only liberated the frontiers, but also delivered to France the whole of Belgium and indirectly the left bank of the Rhine. Robespierre became superfluous, and he fell on July 24th.

On reading these letters one becomes convinced that Engels did not entertain any hazy and nebulous notions about Revolution, but deeply studied the practical details of carrying it out. Thus, Adler tells us in the preface: “Engels heartily welcomed Adler’s plan of becoming a factory inspector; he thought that we had plenty of agitators, but no one who was familiar with the machinery of management, and it is just such people that we will need when we come to power.”

There is a great variety of other problems discussed by Engels and Adler in their letters. I will merely touch upon two of the more important among the latter. I would like to quote what Engels has to say on certain effects of protective tariffs: “At any rate, I was immensely glad to learn from you about the rapid industrial advance in Austria and Hungary. This is the only solid basis for the advance of our movement. And it is also the only good point in the protective tariff system. Big industries, big capitalists and large proletarian masses are artificially fostered, the centralisation of capital is accelerated, and the middle classes are destroyed. On the other hand, while advancing your own industries, you are also rendering a service to England: the quicker British world domination is destroyed, the sooner will the workers here (in England) come to power.”

Further on, we find a reprint of a long letter by Engels to an unknown correspondent on the subject of anti-Semitism. Its substance is briefly summarised by Engels himself:

“Thus anti-Semitism is nothing else but a reaction of mediæval and dying elements of society against modern society, which consists substantially of capitalists and wage-workers; it is therefore only a tool for reactionary aims under an ostensible Socialistic cloak.”

Engels speaks but little of his quiet, scientific research work. On October 23rd, 1892, he writes: “I am now engaged on the third volume of Capital. If I only had had but three quiet months during the last three years, it would have long since been completed. I find that I have already overcome the most difficult passages, much better than I did it last time; at all events, I have now reached the principal difficulty, which has been hampering my work for many years, etc.” Finally, on January 11th, 1894, Engels announces: “The third volume is at last ready for publication.” Thus we see once again the confirmation of what we have already gathered from the “Marx and Engels Correspondence.” We learn from these letters with increasing conviction that “Engels made it his life purpose to be the helpmate of the Genius (Marx) and his work.” (Adler.) In this work Engels assisted even after the death of his friend. “The intelligent reader can discover the traces of affection, of admiration and adoration for his dead friend in his edition of the second and third volumes of Capital” (Adler.) Indeed, there can be no better guide to us than Engels as to the best method of studying the second and third volumes of Capital. This he does very thoroughly in his last letter to Adler on March 16th, 1895; at the same time he sheds light on the origin of some of the chapters. It is to be regretted that the letter is too long to be reproduced; besides, it was already made public by Adler himself in 1908 (Der Kampf, Volume I, No. 6).

Those desirous of learning more should read these letters for themselves. They will be repaid by an abundance of those experiences which the direct intercourse with great personalities alone can give. The reader will become profoundly convinced that the whole life of the two dead leaders, until their last moments, was permeated by feverish longing and ardent desire for the one great goal: the emancipation of the proletariat.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n24-1923-CI-grn-riaz.pdf