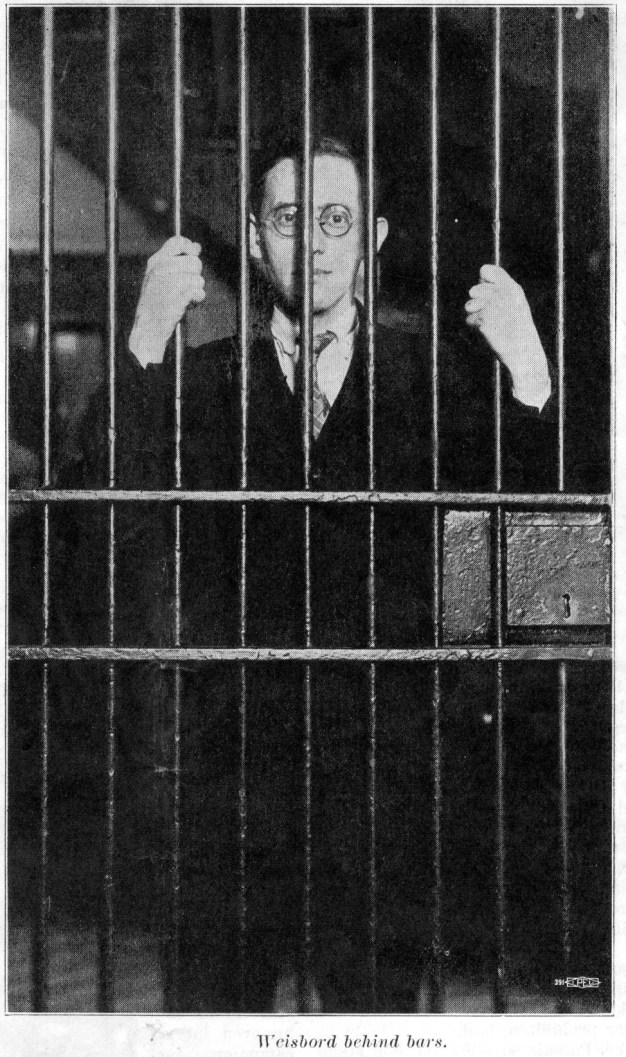

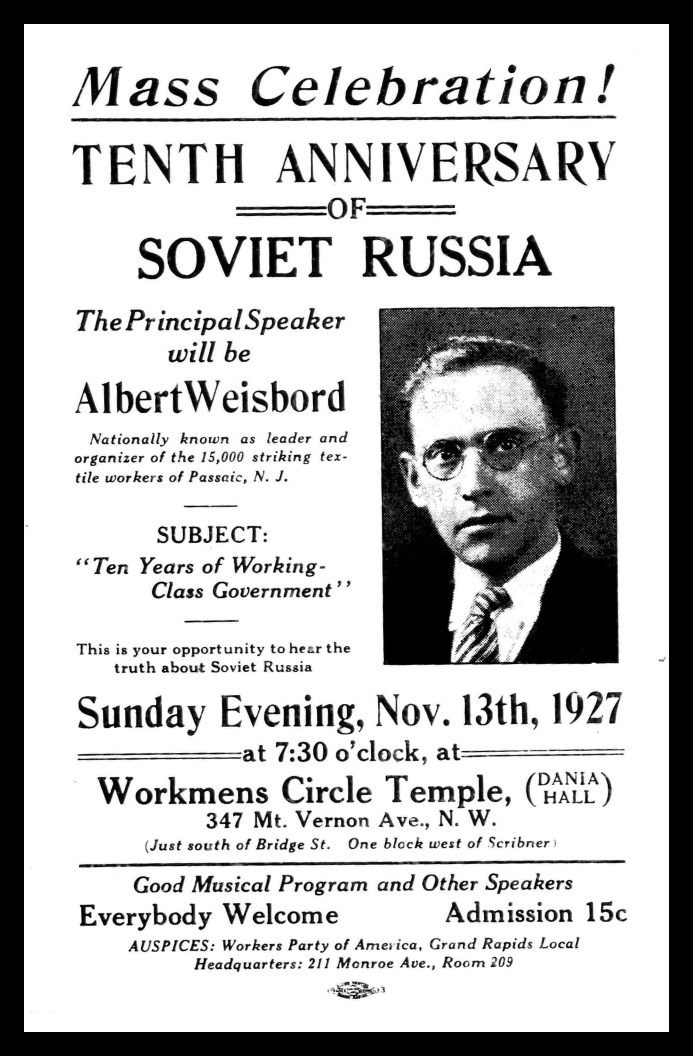

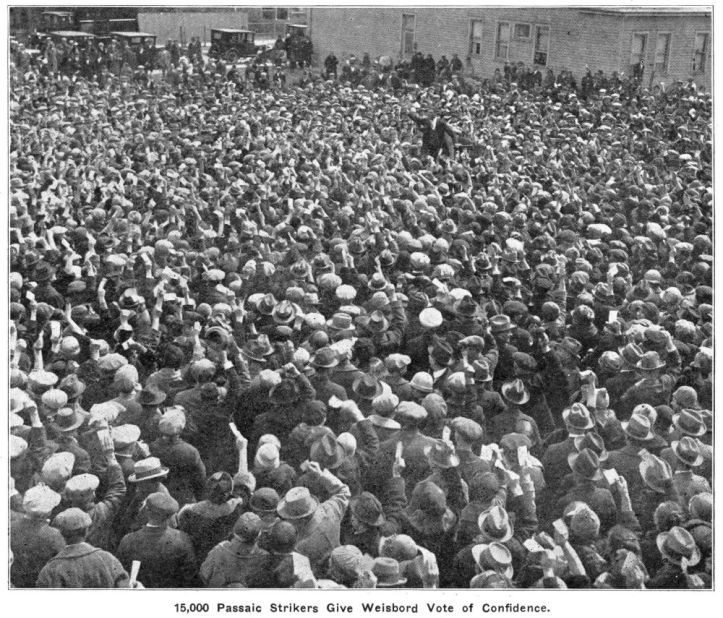

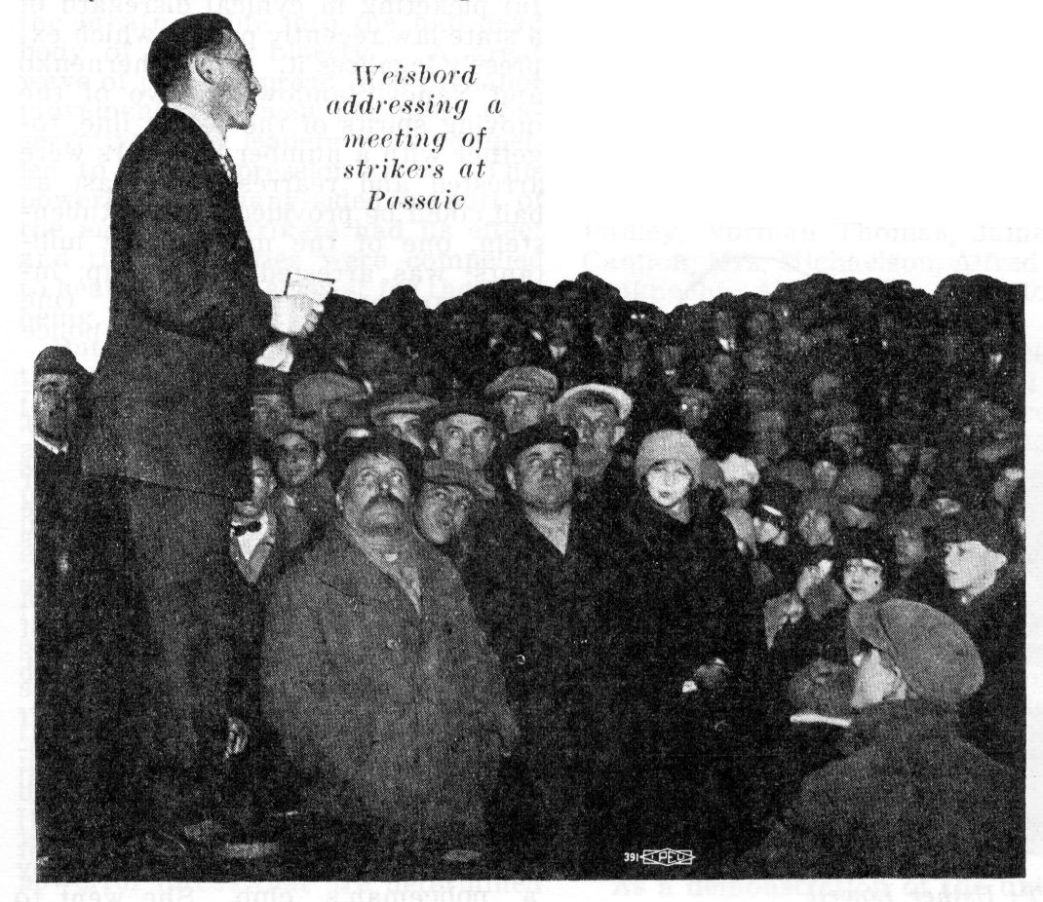

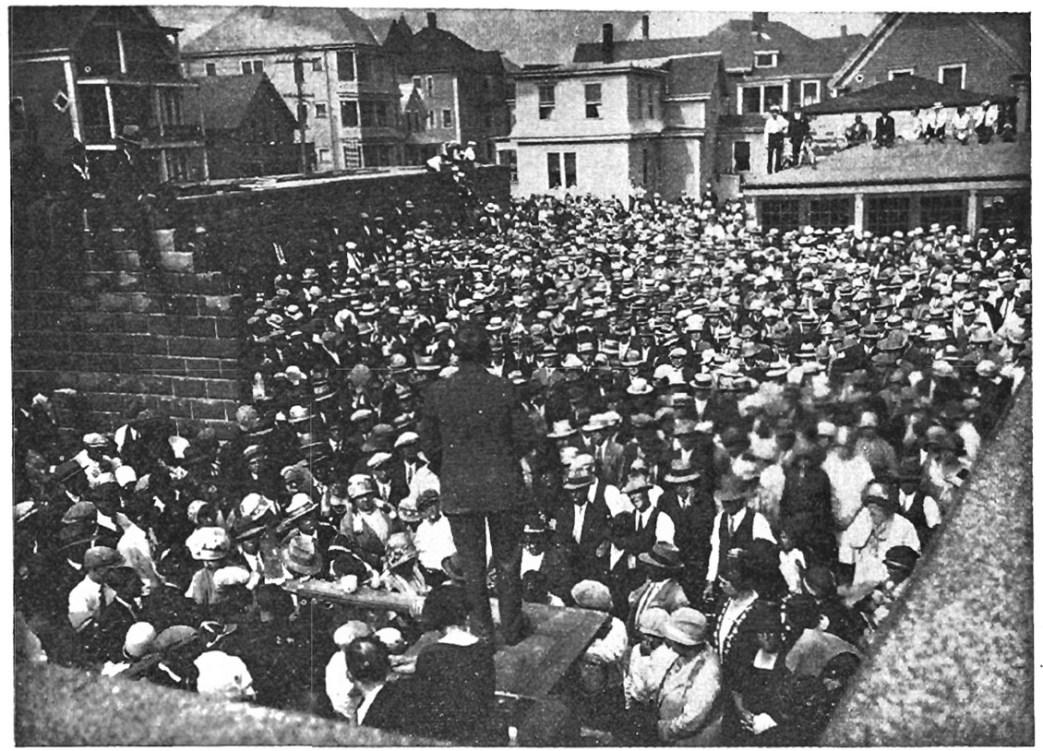

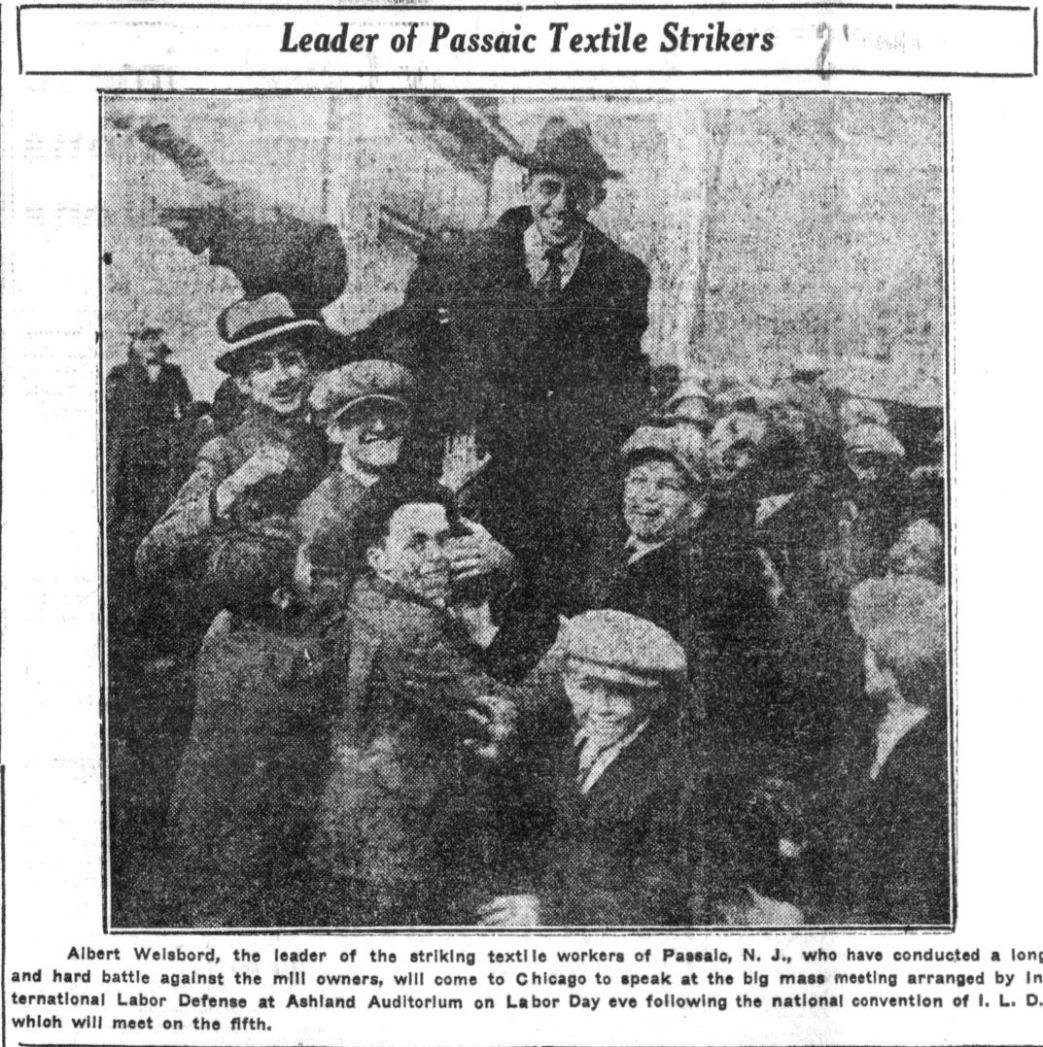

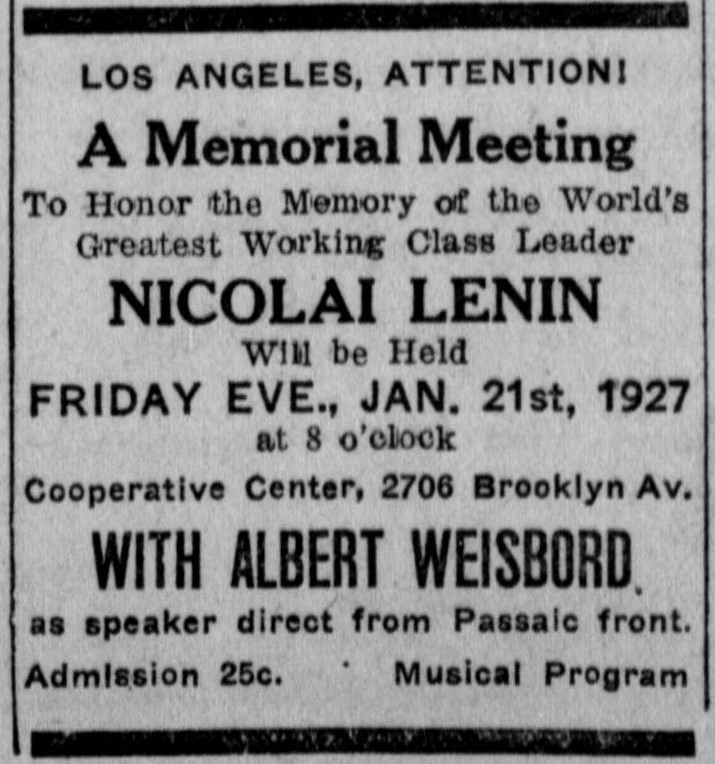

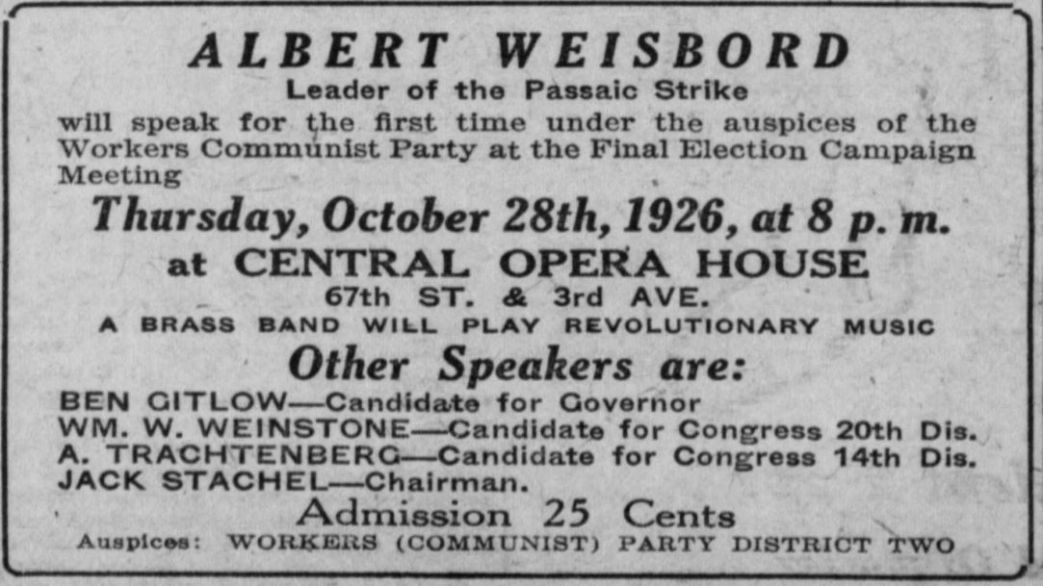

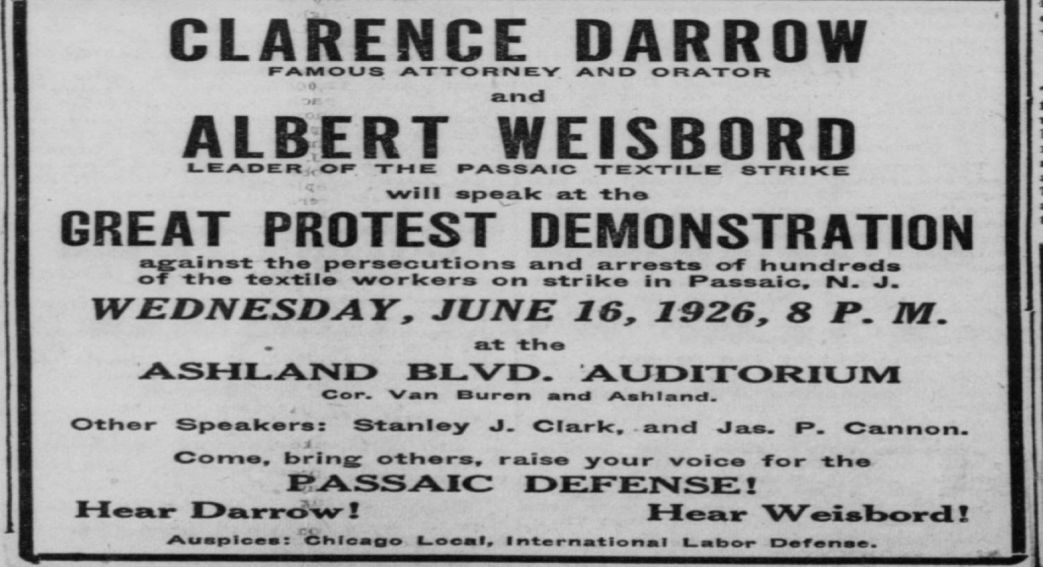

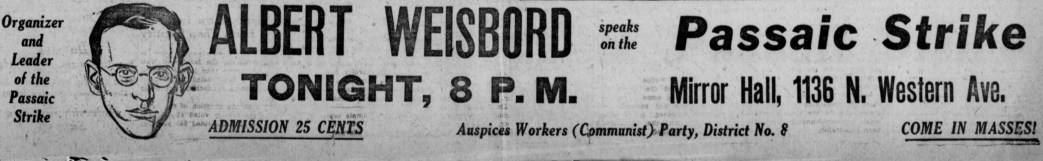

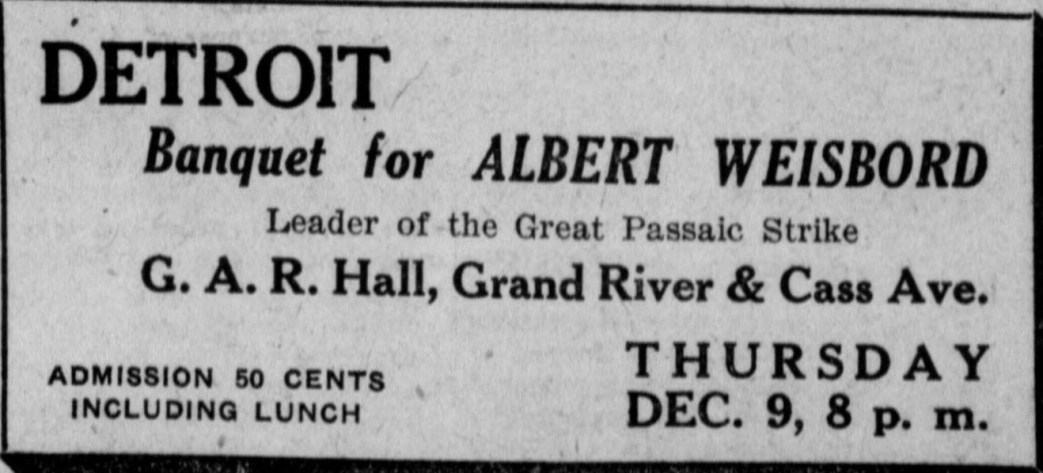

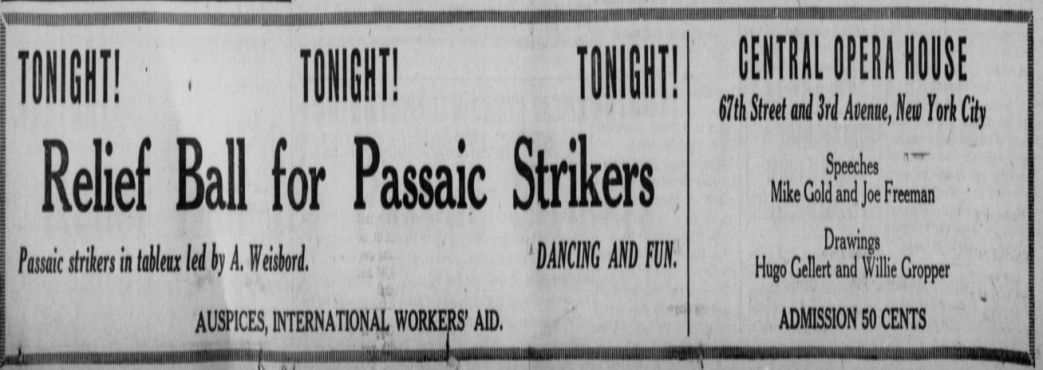

Albert Weisbord (1900-1977) was a member of the I.W.W., the Socialist Party, and National Organizer of its Young People’s Socialist League until he quit, joining the Communist Party in 1924. Emerging as central Party labor activist, particularly among textile workers, Weisbord, with partner and comrade Vera Buch, led the epic Passaic Textile Strike of 1926 . In the course of the fight, they became nationally prominent and would figure in many other textile fights of the latter 1920s. Increasingly isolated after the 1928-1929 mass expulsions from the Party, Weisbord and Buch were expelled as ‘Lovestonites’ in 1931. Though gravitating to the Left Opposition, Weisbord had many differences, and despite negotiations, remained apart from Cannon’s group. Soon Weisbord formed the small Communist League of Struggle and edited its organ ‘Class Struggle,’ which lasted through much of the 1930s. The C.L.S. wound up by 1937. Though tiny, the C.L.S. produced much literature, some of it quite valuable. Here Weisbord gives an extensive defense of his side of the break with the C.P., and in the process offers an illuminating picture of Party life during the period.

‘My Expulsion from the Communist Party’ by Albert Weisbord from Class Struggle (Communist League of Struggle). Vol.1 Nos. 3 & 5. August-September & December 1, 1931.

The reasons for my expulsion from the Communist Party are still a mystery to many party members and sympathizers. My expulsion is not a personal matter. It has given our enemies many a good laugh, as for example, the Jewish Daily Forward. It is a good example of the rudeness and disloyalty of Stalin and his henchmen, and the corrupt bourgeois methods with which they have dominated the Party.

When I joined the Communist Party in 1924, I had at once been forced to plunge into the factional fighting then raging within the Party. Ostensibly the fight was over the question of a Labor Party. But the methods used by the various cliques (Foster, Cannon, Lovestone, Weinstone) soon demonstrated that this was not a Communist fight but an unprincipled fight for power. On the one side stood a group of intellectuals, MELAMUDS (Hebrew teachers) e.g., Bert Wolfe, Bert Miller, Weinstone, Bedacht, Stachel, et. al. On the other side stood a group of MANDARINS (bureaucrats) who had learnt well all the corrupt practices in the A.F. of L. and who were carrying them into the party (Foster, Johnstone, Cannon, Dunne, et. al.)

It was for this reason that as soon as I had registered my opinion with the Ruthenberg group that I left all these factional wranglings and taking the Comintern slogan “To the Masses” seriously got a job in a textile mill, learned how to weave silk, transferred to Paterson and began the work of organizing the masses and building the party.

Up to the time of my expulsion, no one had accused me either of socialist opportunistic tendencies or of an incorrect line in these strikes, or of a wrong attitude to my work, or of bureaucratism.

Why The Expulsion?

How, then, could it be I was expelled, the incredulous reader will ask? Yet the answer is relatively simple. The longer I remained in the Party, the higher up I went in the Party councils, the more I saw of the most rotten corrupt Tammany Hall practices engaged in by all the factional cliques inside the Party. The more I participated in mass work, the more I saw the yellowness, the incapacity, the frivolity, the opportunism of those so-called “Communist leaders”. I began a struggle against the charlatanry of the unprincipled factional fighting, against the bourgeois conduct of our “leaders”. I began to demand that the leaders of the Communist Party go into mass struggles also and take serious responsible posts in the thick of the fight.

This was the real reason for my expulsion: my declared lack of confidence in the leadership and my demand that no one reach leadership unless first having participated in mass struggles and behaved as a foremost Communist in those struggles. However, the Party leaders could not give this for the reason for my expulsion. They had to find other reasons. And so they resorted to lies and to the frame-up.

The first charge made against me was I was a Lovestoneite. Here are the facts:

1. With the death of C.E. Ruthenberg I separated myself ideologically from all groups. For this I was removed by Lovestone from Detroit where I was District Organizer at the time, and not made a member of the Central Executive Committee.

Broke With Gitlow

2. Sent to the Profintern congress in 1928 I there broke formally with Gitlow and presented my own opinions of the defects of the American Communist Party. When the 6th Congress of the Communist International was held I sent across my own views disagreeing with Lovestone on the question of the strength of American imperialism, radicalization, trade union tactics etc. (Letter to Lovestone C.P. secretary, June 11th 1928).

3. Throughout my trade union work I constantly fought the opportunism of Lovestone in Passaic, in New Bedford, in Paterson, in Detroit, etc.

4. Before the 1928 convention I wrote a programmatic article which appeared in the Daily Worker (January 1929) and which had in its title the slogan: “Criticize the too many right wing errors of the C.E.C.”

5. When the open letter came with the organizational instructions calling for the removal of Lovestone, while very much opposed to Foster as being just an opportunist as Lovestone, I welcomed this removal as a blow to opportunism and unprincipled factionalism (Letter to Party Secretariat, March 15th 1929).

6. After the removal of Lovestone I sent the following telegram: (May 25th) “Comintern address very timely and necessary. It definitely smashes the old clique rule of the petty- bourgeois politician officialdom. The Political Committee decision printed Monday’s Daily Worker not strong enough.

“It did not emphatically condemn as it should have, the anti-Comintern slanderous splitting policy of Lovestone, Gitlow, and all others involved. Whole Party must intensify the struggle to clear out all remnants of rotten opportunism inside the Party. I am convinced the whole rank and file now no longer misled are now completely and enthusiastically for the C.I. policy”.

Did Not Print Telegram

This telegram was never printed. The Stachels and the Minors, good swindlers for Lovestone, feeling that this telegram was directed at them were already laying the basis for the frame-up, my expulsion as a Lovestoneite.

7. Finally here is part of the text of a resolution drawn up by me in Gastonia June 11, 1929 (and signed by Jim Reid of the N.T.W.U.)

“1. We enthusiastically welcome the open address of the C.I…We strongly condemn the anti-Comintern slanders…of Lovestone…

“2. Our main tasks while fighting all splitters of every description now are the cleaning out of all remnants of factionalism and rotten diplomacy within the Party and the throwing of our entire and leadership into mass work.

“3. In accomplishing our tasks we must recognize the most serious mistakes, yes, crimes that our leadership has perpetrated. The present leadership not only has kept our party an isolated sect, but it has for years continuously misled the honest proletarian members of our party, driving away many thousands of them from our party.”

8. When after I was expelled, Herberg of the Lovestone group tried to capitalize on it, and in an article in the right wing International Bulletin claimed I was supporting the opposition. I wrote the following letter to Herberg and to Brandler (May 21, 1930) — a letter which Brandler printed but not Herberg. “Everyone knows that I was removed not because I supported the opposition, but quite the reverse, because I declared the present leadership (Foster et al.) was in essence no better than the opposition. Further it is equally well known that I am not a member of the opposition and differ from it on many questions.

The Desertion Charge Exposed

The second charge against me is that I deserted my post in the Textile Workers Union at a critical moment of the struggle in the South. What are the facts?

1. On June 5th, two days before the shooting took place in Gastonia, I had informed Foster that due to my complete lack of confidence in his opportunist leadership, due to the fact that the C.I. called for a struggle against the petty-bourgeois rotten diplomacy which he embodied (see C.I. address 1929). It was impossible for me to accept responsibility for the textile work and that I would tender my resignation at the next meeting of the union fraction as party representative, and what would follow as a matter of course as national secretary of the N.T.W.U.

2. On June 7th the shooting took place. As soon as I heard of it, June 8, I at once got the party secretariat to meet and I made the motion that “I should proceed immediately to Gastonia to stay a minimum of three weeks to take charge of the situation in the field until matters became normalized and the crisis due to the murder frame-ups was over” (Minuets Secretariat June 8th, 1929). The secretariat passed this motion but decided I could leave Sunday June 9th as the National Executive Committee of the N.T.W.U. had been called in for June 8th and 9th. I again informed the secretariat I would announce my resignation as party textile representative to the Communist fraction which was to meet before the N.E.C. meeting of the union.

Motion Voted Down

3. On June 9th the Communist fraction of the N.E.C. met. They approved the decision that I go to Gastonia. I then moved that I be given a leave of absence till the union convention, it to be understood to mean resignation. BUT THAT THIS WAS NOT TO TAKE EFFECT TILL MY RETURN FROM THE SOUTH. The Communist fraction (present Keller, Reid, Dawson, Chernoff, Michelson, and others), UNANIMOUSLY VOTED MY MOTION DOWN. As a Communist I accepted the decision. I DID NOT OFFER MY RESIGNATION AT THE N.E.C. MEETING OF THE UNION.

4. On June 9th I immediately left for the south, having given up my room and stored my things. A large group of Comrades saw me to the train. Jim Reid and Ellen Dawson went with me.

5. I arrived in Charlotte, N.C. Monday morning June 10th. A large party fraction was there (among others, Poyntz, WagenKnecht, Dunne, Crouch, Trumbull, Reid, Dawson). At the fraction meeting I moved that Reid, Dawson and myself at once enter Gastonia in spite of the great danger of lynching for the workers must see that the union is not afraid. Dunne moved that only Poyntz go on the ground that she is a woman and would not be lynched and also on the “political” ground that it is now a defense case and the I.L.D., not the union must take the lead. When this motion seemed doomed to fail, Dunne moved another that only one person go at a time and he presented a list (with himself not too far in front). Taking the authority given me by the C.E.C. as textile representative I declared that the union representatives would go in first and that settled the matter.

Return Is Demanded

6. The next morning June 11th, Reid, Dawson and I were all ready to go from Charlotte to Gastonia when we received a telegram to me signed by Robert Minor, the acting secretary of the Communist Party and dated June 10th. The telegram read: “You are instructed to return immediately.” As soon as possible I called a fraction meeting to take up this telegram. The fraction unanimously decided I should not return, that it would harm the work very seriously as I was the only one with central authority in the field for the union. When we informed the secretariat in New York we received two long distance phone calls categorically demanding I return by the next train. There was nothing to do but for me to return.

7. As soon as I returned to New York City I demanded that I be allowed to go back at once. The necessity for my immediate return to Gastonia was made greater when soon after both Ellen Dawson and Jim Reid returned. This meant that there was absolutely no union organizer in the field at all. And this condition remained until only 10 days before the trial. It took Bill Dunne over 14 days before he ventured to go into the city of Gastonia from Charlotte. To my plea to be allowed to return, the secretariat merely ordered me to stand trial before it next week.

Charged With Running Away!

What was my astonishment to learn when I appeared before the secretariat that I was charged with running away from the south! And it was for this I was removed from the C.E.C. and suspended from the Party, later expelled by the C.I. How shall we designate this if not by the term frame-up?

8. Soon afterwards the Secretariat ordered a fraction meeting of the N.T.W.U. At this fraction meeting Foster appeared and in the name of the Party Secretariat demanded that I resign as national secretary of the union and that he fraction vote for it. There followed a long discussion. The fraction was not quite in harmony with this policy but after I declared that I would not fight the order of the Secretariat, the fraction agreed. At the N.E.C. meeting of the union I resigned. Now I am charged with resigning from my post and expelled for that reason!

9. Later the N.T.W.U. called a national convention in Paterson. I came to the meeting. I was met at the door by a party committee who told me that it was party orders that I was not to enter the hall as I was under suspension and they thought the workers would give me an ovation, thus upsetting the party’s plans for my elimination from the union. As a disciplined Communist I obeyed. The next day in the Daily Worker there appeared an article by Amter charging me with being too yellow to appear to face the charges! And this while I was officially still a member of the party and under its discipline!

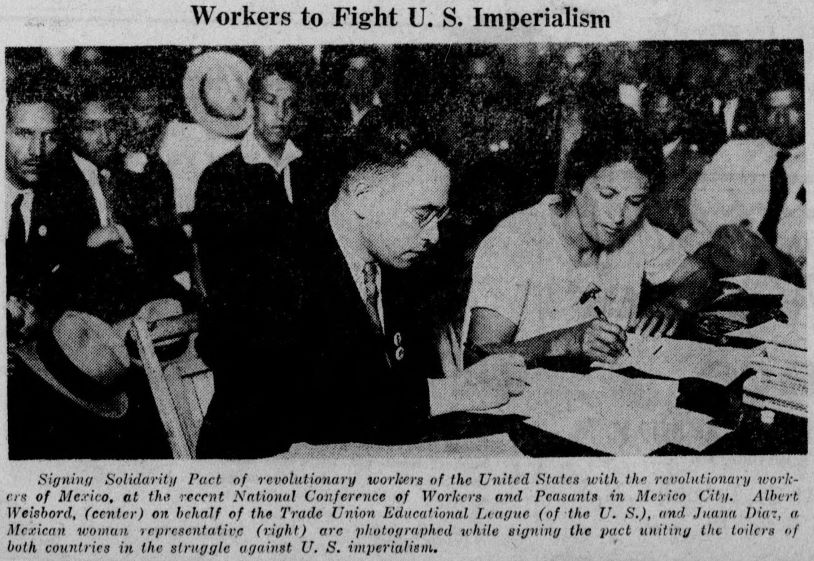

Who were the people who had me charged with “Lovestoneism”? The very ones who had been the worst Lovestonites, those who had formed the right end of the Lovestone faction (Stachel, Weinstone, Minor and Co.) Stachel could never forget how I had testified that he had tried to swindle the C.I.–affirming that Pepper had gone to Mexico and trying to use the evidence of my own trip to Mexico to prove it! As for the right-wing policies of Weinstone, these had come thoroughly into the open in the 1926 Patterson Strike where I had been forced into a head-on collision with his Menshevik theories (June issue Class Struggle: Crucial Moments in Textile Strikes). Inside the Lovestone faction it was the Weinstone-Stachel clique against which I had been forced to struggle the most. When, due to the capriciousness of Stalin, they were momentarily put at the helm, they were quick to seize the opportunity to expel me.

Who were the people who charged me with “running away from the South”. It was again the Stachels and the Weinstones who never ran away from a fight because they saw to it that they never had to come near one. The Minors, who, Southern gentlemen that they are, would rather leave it to the East Side Jews or Poles to organize the Southern workers? The Dunnes and Johnstones who carefully avoid the scene of action or conveniently arrive there too late and never take responsibility for the action! The Browders who go through a Chinese revolution and learn nothing except that Chinese textile unions sweep their floors clean! The Fosters who enter a struggle only to make a speech or so, but who, when they were organizers (in the far-off past) actually betrayed the workers (Foster record Steel Strike, 1919)! Yes, these are exactly the people who levy the charges.

Was it correct for me to have tendered my resignation as the Central Executive Committee textile representative? The Secretariat threatened me with immediate expulsion unless I at once repudiated my resignation. This I did. However, I stated:

“At the time I offered my resignation I felt that I had such serious political disagreements with the present leadership that if I had not resigned I would have to be removed and that with such opinions I could not maintain the responsible party post of CEC textile representative and that under such circumstance , especially since I was now leaving for the South, that it would be better for a textile comrade to take hold of the post of secretary of the union. It was clearly understood that the union change of secretaryship must take place in such a manner that the union would not be hurt by such a change. A previous telegram giving my position had been suppressed. I was desirous of demonstrating my political disagreements in some manner before leaving for Gastonia, due to the terror of the bosses I might never have the opportunity again.” (Statement to Secretariat, June 19, 1929)

Of course, my tendering my resignation under the circumstances was correct. If any criticism is to be made it is that I did not wait to organize a strong faction inside the union, that I did not mobilize the textile workers to fight the frame-up artists and puppets in the Party.

Once my suspension was decided upon, a frame-up was necessary to put it over on the party and union membership. A whole regiment of “reasons”, most of them pure lies and fabrications were “discovered.” It was discovered that I “sold-out the Passiac strike.” It was discovered that I “hid on a roof in the New Bedford strike.” It was discovered that I “had wrong union policies”, that I had a wrong strategy in the South, a wrong policy in Elzabethtown, that I had wrong defense slogans, that I was a pacifist, a careerist , a syndicalist, a factionalist, etc., that I was for the bourgeois democratic revolution in America (no less!) And for an opportunist labor party.

The only part of these ridiculous “charges” which deserves words to answer is that touching on policies. On the “wrong union policies” I can say we never had a disagreement in the National Executive Committee of the National Textile Workers Union on any serious question and none on the South. The “rolling wave strike strategy”, proposed by myself, was unanimously adopted by the N.T.W.U. And approved by the Polcom of the C.P. itself. This strategy is in itself important enough for an article. Finally as to the “wrong Gastonia defense slogans”, all I need to say is that at the same time I was removed from all posts by the party leadership, no defense slogans had yet been issued.

As for the charges of careerism, individualism, etc., are they to be treated seriously? We ask the people who made these charges to show us a single thing they did for the American proletariat to deserve the posts they have. We ask them whether they ever did a thing without considering “would it affect my job, my career”. We are in our “1902 period” in America for we have not yet really tested our leaders, because we are still infested with the worst type of shysters and sharpers which our “1905 dress rehearsal for the revolution” will clean out. Just as Lenin sounded the alarm in 1902 in Russia so must we today in the United States.

After my suspension from the Party I cabled an appeal to Moscow denouncing the frame-up and demanding a trial and the right to appear personally in Moscow. You see, I naively imagined that the crookedness and corruption of the marionettes in the U.S. did not come from the Stalin-Lozofsky regime. At that time I wrote that “the C.I. calls upon every party member to finish what the C.I. has begun — the elimination of the present leadership fundamentally vitiated by petty-bourgeois political tendencies and rotten diplomacy and for the creation of a leadership actually tested in the fire of proletarian struggles…” (Statement to the Secretariat June 19, 1929)

I was soon disillusioned. I learned through the New York Times that the C.I. had expelled me. From the Imprecorr I learned the reason: It was for WHITE CHAUVINISM! No more, no less. The charges were made by Lozofsky himself who demanded that I be thrown out of the Party “like a rag”. What are the facts?

1. I was the first to speak on the Negro question in the Gastonia strike at the very beginning, raising the slogan of equality for black and white workers. All the Southern papers carried the story of my speech (Houston “Democrat”, Atlanta “Constitution”, etc.) Furiously denouncing it and declaring this alone meant the N.T.W.U. would never have the slightest chance in the South.

2. In the face of the terrific reaction that set in, our whole fraction in the field capitulated on the Negro question, refused to carry out our line, strung up a wire between Negro and White workers, etc. These capitulators include some still leading the Party. The Polcom sent down Jack Johnstone to correct their line, to stiffen them up, to take leadership. Within a week Johnstone had run back to New York City – without permission. He proposed in a written series of motions the N.T.W.U. build TWO UNIONS in the South, one for Negroes, one for Whites, declaring that the Negroes themselves wanted this! These outrageous proposals were supported by Browder. It was I who took the lead in denouncing them. The Negro comrades sent a cablegram to Moscow denouncing the white chauvinism of Johnstone-Browder. Johnstone was yanked out of the South – for which he was desperately manoeuvering – and I was sent down to carry out the line of the Party.

3. The first thing I did was to counteract the poisonous chauvinism of Johnstone and Wagenknecht and to break the sabotage of the fraction in the field. None of the organizers at first would speak to the strike committee on the simple proposition of complete equality in the union. I was left to do it myself. I had to get a vote in the Gastonia Strike Committee. I had to go to Bessemer City to get a vote there. I had to call the meetings in the Negro quarter. In order to get a little help I got the I.L.D. attorney to make a five minute talk to the Strike committee on the necessity of black and white to stick together. I worked out his remarks and he told them in the Southern language to which they were accustomed. All of the organizers admitted that I was successful in convincing the majority of the Strike Committee.

4. What were the results? I got the Strike Committee to vote for the proposition “Full equality in the union”. For the first time white men and women held a meeting in the Negro quarter standing side by side with the Negro workers. It was a great move forward. Some of the comrades now saw their error and began to help.

But as Party representative I was not satisfied with this. While we now hammered home before the union “Full equality in the union” I laid down a much more advanced program for the communists. As I wrote in a letter to Beal soon after the strike began (Letter of April 20, 1929):

“On the Negro question, there must be absolutely no compromise. OUR UNION STANDS AND FIGHTS FOR FULL ECONOMIC, POLITICAL, AND SOCIAL EQUALITY FOR ALL WORKERS INCLUDING NEGRO WORKERS. Further than that you as a Communist and all leaders as Communists, must lead the way by personally fraternizing with the Negro workers, making them your personal friends. While at UNION MEETINGS it is not necessary AT THIS STAGE OF THE GAME to advise the Southern workers with deep prejudices that they have on the Negro question – to intermarry or even have as their personal friends Negro workers, nevertheless, you AND THE OTHER ORGANIZERS BY YOUR PERSONAL CONDUCT BY MAKING PERSONAL FRIENDSHIPS WITH NEGRO WORKERS CAN DEMONSTRATE IN ACTION THAT YOU AS A COMMUNIST CAN WIPE OUT COLOR DISTINCTION. Please see that this line is rigidly adhered to.”

5. When I returned to New York city and reported everything, the Polcom by express motion passed a decision that on the whole I CARRIED OUT THE PARTY LINE.

Now what shall we say when we learned that I am expelled as a white chauvinist but Johnstone is promoted to the Polcom and Browder made head of the Party?

Here stands Lozofsky and the whole Stalin apparatus fully exposed. Are they not rags, these gentlemen, who must be thrown out of the revolutionary movement?

The Communist League of Struggle was formed in March, 1931 by C.P. veterans Albert Weisbord, Vera Buch, Sam Fisher and co-thinkers after briefly being members of the Communist League of America led by James P. Cannon. In addition to leaflets and pamphlets, the C.L.S. had a mostly monthly magazine, Class Struggle, and issued a shipyard workers shop paper,The Red Dreadnaught. Always a small organization, the C.L.S. did not grow in the 1930s and disbanded in 1937.