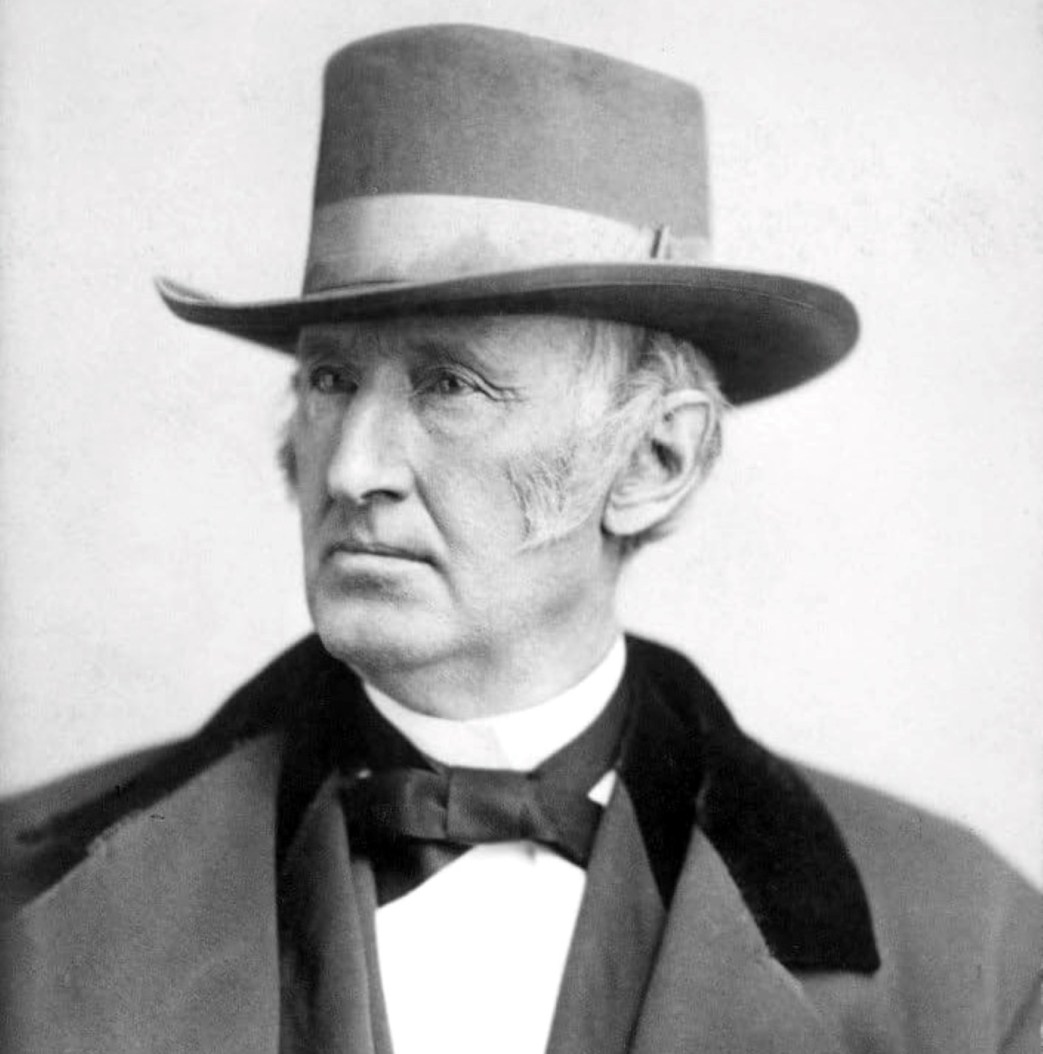

“When I want to find the vanguard of the people, I look to the uneasy dreams of an aristocracy and find what they dread most.” Wendell Phillips, “On The Labor Question” given in the immediate aftermath of the Paris Commune, 1871.

Frank Bohn argues that November 27, birthday of preeminent 19th century radical Wendell Phillips, be set aside as an international day of celebration for the man and his cause; the liberation everywhere of the oppressed, and by extension, all of humanity.

‘The Wendell Phillips Centenary’ by Frank Bohn from Revolt (San Francisco). Vol. 2 No. 21. November 18, 1911.

November 27th is a day which should be celebrated by every Socialist and Socialist party local in the land! More than this. It should be an international day of rejoicing. Wendell Phillips was one of the first great modern internationalists. It is impossible in the brief space here taken to give any adequate conception of the character and services of Phillips. For thirty years he was one of the most uncompromising enemies of chattel slavery. He entered this fight when it meant to him loss of his profession, loss of friends, loss of respectability, loss of everything in the world but a good opinion of himself.

It is sometimes thought that chattel slavery was always opposed in the North, especially in New England. This is not true. New England ships brought the slaves to America originally and later Northern manufacturers sold their products in the South. The anti-slavery movement was at first hated as much in Boston as in Charleston, South Carolina. It was on the occasion of the mobbing of William Lloyd Garrison in Boston, when the latter was hurried off to jail in order to save his life, that Phillips resolved to throw in his life with the abolitionists. For more than thirty years he fought the slave institution, not in the South, but in the North. The story of this war of the abolitionists upon slavery is to the modern revolutionists the most precious chapter of American history. After twenty years of agitation the abolitionist society numbered hardly a thousand members. They never hesitated. They were never silent. They refused absolutely to compromise in any way whatever. When, later, parties arose which aimed to abolish slavery in the territories only, the abolitionists fought those parties.

Wendell Phillips and William Lloyd Garrison despised the Constitution of the United States because that Constitution upheld slavery. To them the Northern compromisers were “doughfaces.” In 1850 the position of the mighty Daniel Webster upon the slavery contest was very much. like that of Theodore Roosevelt upon the labor movement at present. Phillips’ scourging of Webster will ever remain one of the greatest philippics in American literature. It should be read by every Socialist.

The following story will indicate Phillips’ attitude and method of fighting. Then as now 99 per cent. of the priests and parsons wiggled and squirmed on the subject of slavery. Phillips spoke in Cincinnati at a time when feeling ran high. A Methodist clergyman from Kentucky came to hear him. After the meeting he burst out upon Phillips.

“Why don’t you come down to Kentucky where I live,” said the preacher, “and agitate anti-slavery down there? You don’t dare to!”

Of course, Phillips knew that if he went into a slave State to speak he would be killed, so he made reply to the parson as follows: “You’re a preacher, aren’t you?”

“Yes.”

“You are preaching against eternal damnation and in favor of salvation from hell, aren’t you?” “Yes.”

“Then why don’t you go to hell to preach salvation?”

The Civil War proved the soundness and rectitude of the abolitionist position. There could be no compromise between two economic systems fundamentally different in character.

But it was during the twenty years following the Civil War that the life of Phillips stands out as no other in the history of the Nation at any time.

In 1865 he was 54 years of age. A generation of the most ardent service had been crowned with victory. For the first time in his life he was respected by his fellow citizens. The fashionable people of Boston, who, when they had seen him coming along the streets in years past drew their shutters, now flocked to do him honor. He was invited to deliver an address at Harvard University, which had always shut its doors in his face. But his revolutionary spirit was not content. All of the other great abolitionist leaders spent their declining years talking of ante-bellum days. No so Phillips. With the close of the struggle against chattel-slavery the struggle against wage-slavery began. He helped organize the labor party of Massachusetts and was its candidate for Governor in 1871. Some of our New England comrades still remember him standing in union halls and in open places forty years ago urging class-conscious action upon the workers. Labor, he said, should rule the world. It was the year of the Paris commune. In a great speech in Boston he defended the communards. His advocacy of the Irish revolt endeared him forever to that race, and among the most earnest supporters of this Puritan New Englander. were Irish Catholics.

It is almost impossible at this time when the working class of America is so far in its road to success to conceive of the hatred held for the labor movement by every element of respectable society forty years ago. Unions must needs be organized in the dark. A labor party was denounced as “un-American,” “un-patriotic,” in every way a most wicked thing. And here we come to the climax of Wendell Phillips’ career. During this thirty years of anti-slavery fighting, he had necessarily made the warmest friendships of his life. Many of these friendships were among that coterie, of famous literary people of which New England is so proud.

When Phillips espoused the cause of labor many of these friends deserted him. Even Ralph Waldo Emerson refused to have anything more to do with him. It made a difference, said Phillips, whether the people were fighting slavery in the South or slavery in New England. Before that they had fought other people’s crimes, now they were asked to fight those for which they themselves were responsible.

Wendell Phillips forty years ago advocated the ownership of the tools of production by those who used them. Even this extreme view had been popular among the literary people of New England in the days of Fourierism and the Brook farm. The earlier utopian Socialism of 1840 was to be obtained by Sunday School societies. But Phillips advocated the class war.

We would not make the attempt of establishing Phillips’ position in the mind of the working class by making a comparison with others who have distinguished themselves in the cause of human liberty and progress. But it is not too much to say that American history must accord him a position apart from all others. During his whole life he was a torch-bearer always far in advance of any considerable number of those who followed him. He was as little endangered by vanity, by ambition, or by any desire for commendation, as by love of pelf or power. For thirty years he wanted nothing on earth but freedom of the black slave and then for twenty years more he wanted nothing on earth but the freedom of the white slave, of women and the freedom of the race from the institutions and influences which kept it from rising.

In the minds and hearts of the working class his memory will always be enshrined with those of the very few who, when our cause was weak and when our class did not understand itself. gave all that he was and all that he had or could have had freely and fully to the future.

Note. November 27th comes upon Monday. Would it not be fitting for Socialist party locals everywhere to have à Phillips meeting upon that evening or upon the preceding Sunday? Almost any good public library contains one of the two biographies of Phillips. There is also a most incomplete and unsatisfactory volume of his speeches. Most of his great orations are contained in the standard collections. His speeches upon the Philosophy of the Abolitionist Movement (1854) and upon the Labor Movement (1871), are especially recommended. In the December number of the International Socialist Review there will appear a notable article on Phillips by Comrade Charles Edward Russell. Russell’s poem on Phillips will accompany his article.

Revolt ‘The Voice Of The Militant Worker’ was a short-lived revolutionary weekly newspaper published by Left Wingers in the Socialist Party in 1911 and 1912 and closely associated with Tom Mooney. The legendary activists and political prisoner Thomas J. Mooney had recently left the I.W.W. and settled in the Bay. He would join with the SP Left in the Bay Area, like Austin Lewis, William McDevitt, Nathan Greist, and Cloudseley Johns to produce The Revolt. The paper ran around 1500 copies weekly, but financial problems ended its run after one year. Mooney was also embroiled in constant legal battles for his role in the Pacific Gas and Electric Strike of the time. The paper epitomizes the revolutionary Left of the SP before World War One with its mix of Marxist orthodoxy, industrial unionism, and counter-cultural attitude. To that it adds some of the best writers in the movement; it deserved a much longer run.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/revolt/v2n21-w30-nov-18-1911-Revolt.pdf