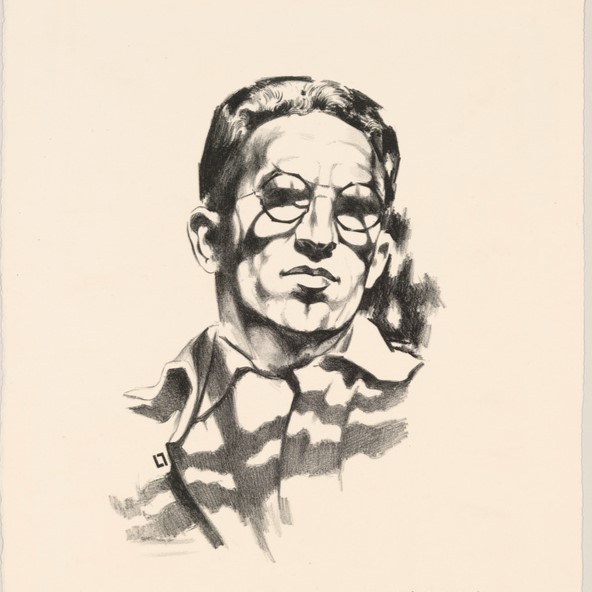

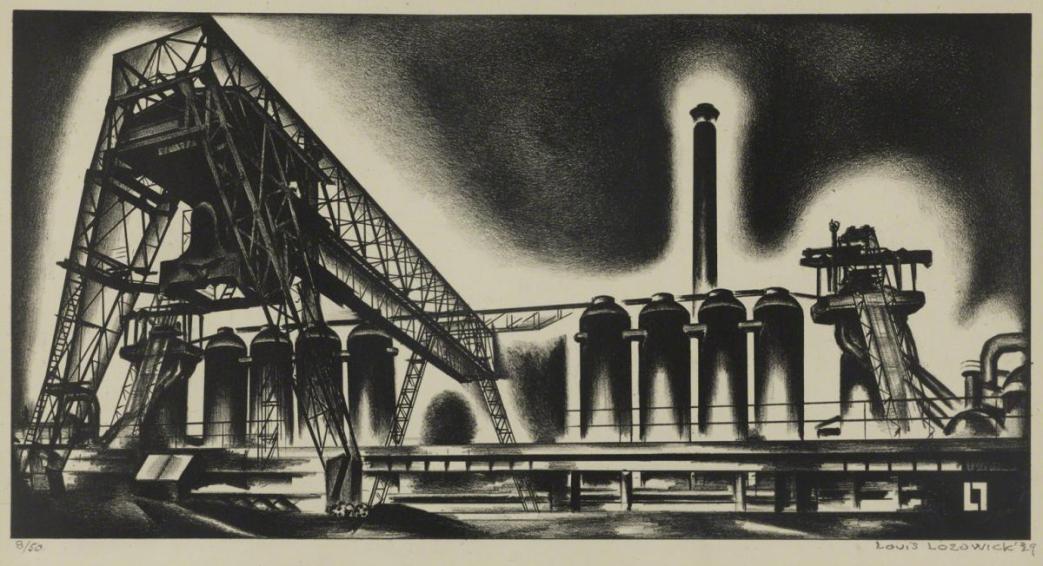

Louis Lozowick, whose work has featured here many times, with a major statement of his creed. Lozowick (1892-1973), a central figure in the world of radical arts, was born in Ludvynivka Ukraine and studied at the Kiev Art School from 1903 to 1906 when he came to the United States and continued art studies at Ohio State University. Louis traveled extensively in post-war revolutionary Europe before returning to the US in 1924 where Lozowick lectured on modern Russian art for the Société Anonyme. In 1926 he joined the executive board of the New Masses, became secretary of the American Artists’ Congress and was active in the John Reed Clubs. His work appears in many issues of New Masses. Known for his WPA work, including murals, his work exemplified the Art Deco and Precisionist movements.

‘Towards a Revolutionary Art’ by Louis Lozowick from Art Front. Vol. 2 No. 8. July-August, 1936.

WHEN a new art current emerges, persisting over a long period of time, comprising a large number of adherents, exhibiting a continuity of development, embodying a solid system of principles, we are justified in assuming that a fundamental change in society has taken place. In a broad generalization: Italian art of the fourteenth century, Dutch art of the seventeenth century. French art of the nineteenth century each compared with the art of the century preceding it might be taken as characteristic illustrations. Similarly perhaps in even broader generalization the emergence of a revolutionary art in the Soviet Union as in Japan, in Mexico as in Hungary, in Holland as in the United States, points to the presence of a revolutionary world situation, is in fact both a symbol and a product of that situation.

The capitalist press in a moment of unconscious clairvoyance has referred to the revolutionary artist as “class-struggle” artists. Excellent appellation, for it identifies the revolutionary artist unmistakably. Like the artists of every age worth considering, the revolutionary artist proceeds from direct experience of immediate reality, knowing, however, that experience and reality have no meaning except in concrete connotation. The revolutionary artist proceeds from the patent factor that the class antagonisms, always present in capitalist society, have reached the acute stage of open class war. When capitalism “plans” industry by curtailing production, “solves” starvation by destroying food and degrades the human personality, science and art to cash payments (to limit ourselves to a few short items), the conclusion is inescapable that the basic assumptions underlying capitalist society have lost their validity; that it has reached a stage of insoluble internal contradiction which only a shift of power can resolve.

In all parts of the world there are signs of incipient and open revolt against the system. The organized working class, joined by growing numbers of intellectuals, farmers and other elements, and guided by the philosophy of Karl Marx, is the only force that can abolish it. Artists like others, whether they want it or not, whether they know it or not cannot remain outside of the situation described. We notice, in fact, everywhere the parallel process of fascization and radicalization of art as representative of the two forces in conflict. (The meaning of the so-called American school is transparent. On one hand it attempts to corner the art market against foreign competition; on the other hand it is the first step in the direction of a more aggressive chauvinism, a home style. Whether it will also take the last step will depend entirely on how far reaction travels in the United States.)

When the revolutionary artist expresses in his work the dissatisfaction with, the revolt against, the criticism of the existing state of affairs, when he seeks to awaken in his audience a desire to participate in his fight, he is, therefore, drawing on direct observation of the world about him as well as on his most intimate, immediate, blistering, blood-sweating experience, in the art gallery, in the bread line, in the relief office. But as already indicated experience to him is not a chance agglomeration of impressions but is related to long training, to habits formed, to views assimilated and entertained at a definite place and time; to him. experience acquires significant meaning by virtue of a revolutionary orientation. In sum, revolutionary art implies open- eyed observation, integrated experience, intense participation and an ordered view of life. And by the same token revolutionary art further implies that its provenance is not due to an arbitrary order from any person or group but is decreed by history, is a consequence of particular historic events.

Although the revolutionary artist will admit partisanship he will most emphatically deny that it need affect unfavorably his work. Obviously, if disinterestedness were in itself a guarantee of high achievement all the tenth-rate Picassos would be geniuses; if social partisanship resulted necessarily in inferior art Goya and Daumier would have to be erased from the pages of art history. Nor does partisanship narrow the horizon of revolutionary art. Quite the contrary, the challenge of a new cause leads to the discovery of a new storehouse of experience and the exploration of a new world of actuality. Even a tentative summary will show the vast possibilities, ideologic and plastic; relations between the classes; relations within each class; a clear characterization, in historic perspective, of the capitalist as employer, as philanthropist, as statesman, as art patron; the worker as victim, as striker, as hero, as comrade, as fighter for a better world; the unattached liberal, the unctuous priest, the labor racketeer; all the ills capitalist flesh is heir to persons and events treated not as chance snapshot episodes but correlated among themselves shown in their dramatic antagonisms, made convincing by the living language of fact and made meaningful from the standpoint of a world philosophy. The very newness of the theme will forbid a conformity in technique.

Strictly speaking, contemporary revolutionary art is not altogether new. It already has an impressive history and many precursors of great talent. Almost as soon as industrial workers organized as a class in the early part of the nineteenth century, pictures began to appear which showed labor in its social position and historic role. Tassaert, Jeanron, Adler, Laermans, Courbet, Daumier and many others pictured the working class in its daily occupations as well as on barricades and in strikes.

If contemporary revolutionary art stems in a continuous line from the artists enumerated, it descends. in a collateral Wine from many more, throughout the ages. For the overwhelming mass of art across all history-Egyptian, Byzantine, Renaissance, Dutch, French. etc., has been art derived from social experience and directed to social ends, an art frankly partisan for one or another historic class. Thus the revolutionary artist has a rich cultural heritage to draw upon, absorb and utilize in his efforts toward the formation of a style appropriate to his needs. But just as no style can be created out of a vacuum, so no style can be carried over from one period to another without change. Certain elements in the cultural heritage such as the religious genre and pure abstraction are not usable at all. Other elements may have to be radically modified. The problem of how to utilize the cultural heritage will be best solved in practice–revolutionary art being still in process of formation. As an extreme instance one may take the revolutionary artist who has recourse to the method of surrealism. Like the surrealist he records within the same frame a series of events. distributed over several points of space and time (the surrealists are the latest but by no means the only ones to use this device which is, in fact, quite ancient), but unlike the surrealist he gives the events logical unity and ideological meaning; like the surrealist he uses a meticulous technique but unlike him he rejects its mystical application. Where the surrealist postulates irrationalism and “automatism, the revolutionary artist must substitute reason, volition, clarity. The message will fail of its object unless it is clear and forceful; the meaning will not carry conviction unless it is effective. And this, by the way, is only another aspect of the form-content relation. It is there- fore a perversion of the truth to accuse the revolutionary artist-as is done so often of disregarding the problem of form. Beginning with Marx and Engels (who presumably knew their own minds) the importance of formal excellence in art has been stressed by every Marxist who has written on the subject. The Marxists maintain, however, that while all artistic creation implies formal organization, it cannot be reduced to it, much less exhausted by it. Content and form are mutually interpenetrating; both derive from social practice, are outgrowths of social exigencies.

To illustrate by an example (one among many) from the history of Christian art. Early Christianity was a movement of the enslaved, the impoverished and oppressed; their art of the Catacombs (second and third centuries) followed. the style and imagery of Roman fresco painting and incorporated in their work the humble subject-matter from their own life and beliefs; stone masons, agricultural workers, the figure of Christ. (Orpheus) as the Good Shepherd, all done in subdued colors and treated with a directness and simplicity which invite intimacy between image and audience. With the spread of Christianity among larger masses, with the rise of a priesthood and the growing entrenchment of the church as part of the state apparatus, new elements came into Christian art (fifth and sixth century): the formal dignity of the Byzantine, elaborateness and solemnity. Art emerged from the underground catacombs to make its abode in caste-ridden houses of worship. The image of Christ as the Good Shepherd gave way to the concept of Christ as Lord, as powerful ruler with all the attributes of regal authority, throne, scepter, splendid raiment, an increasing army of royal attendants (pictorial elements these, inseparably both content and form). The resplendent colors, the precious stones, the rigid formal dignity served as a wall to keep the congregation at a reverent distance. Christianity had become the state religion, admirably responsive to the needs of the ruling autocracy.

In this example which could be profitably analyzed in greater detail, we see with striking clarity how old forms are grafted on new contents, how new forms evolve to meet new social situations, how reciprocally related are all the elements involved and how contingent on the underlying class structure. If historic precedent is any indication the revolutionary artist may look confidently to the development of a style appropriate to his aims. For the present, revolutionary art is still a direction but a direction well defined as to its source and its goal.

A revolutionary orientation must ultimately affect even the treatment of old genres such as still life and landscape. Which brings up the question of whether the revolutionary artist should at all deal with them. The formation of a revolutionary art is not the task to be achieved. by one work or even by one artist. It is the labor of a movement; whether one member or another occasionally paints a still life or a landscape is, viewed in large perspective, of little consequence.

A more serious question is: can the artist who has been trained in the dispassionate contemplative tradition change into a participant and revolutionary? Unquestionably yes–with reservations–even as the conditions under which he lives and to which he must adjust himself, change. In proportion as his ideology forms and matures and becomes part of his mental make-up his art will seek to express his feelings and thoughts. But the process is not mechanical; it depends on the mobility of character in the individual artist, on how set he is in his ways; it may be very painless with certain artists, very slow with others and all but impossible with some. The process should be in every way encouraged–it cannot be forced. But again, in a movement of such major proportions the behavior of a few single artists is inconsequential.

We are in the midst of a vast, decisive transformation, economic, social, cultural, by which no one is unaffected. Where among contemporary art currents can we look to the expression of this momentous event? In the moribund symbolism of the doddering academy? In the “hypnagogic” trances of the surrealists? In the tabloid thrills of the American school? Whatever else might be said about revolutionary art, it does not play sycophant to “disinterested” collectors, nor cater to the speculative needs of the dealers. It grows out of profound conviction of the artist and the living issues of society. Fortified by a revolutionary tradition (present–if neglected–in American art as in the art of other countries) the revolutionary artist stands before an ideal and a task to which all artists not directly interested in the maintenance of the status quo can rally. To make art auxiliary to the building a new society is not to degrade but to elevate it. An art to be valuable must be historically on time. Revolutionary art makes sure to be in the vanguard rather than in the rearguard of history.

Art Front was published by the Artists Union in New York between November 1934 and December 1937. Its roots were with the Artists Committee of Action formed to defend Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural soon to be destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Herman Baron, director of the American Contemporary Art gallery, was managing editor in collaboration with the Artists Union in a project largely politically aligned with the Communist Party USA.. An editorial committee of sixteen with eight from each group serving. Those from the Artists Committee of Action were Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Zoltan Hecht, Lionel S. Reiss, Hilda Abel, Harold Baumbach, Abraham Harriton, Rosa Pringle and Jennings Tofel, while those from the Artists Union were Boris Gorelick, Katherine Gridley, Ethel Olenikov, Robert Jonas, Kruckman, Michael Loew, C. Mactarian and Max Spivak.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/art-front/v2n08-not-n7-july-aug-1936-Art-Frontpdf.pdf