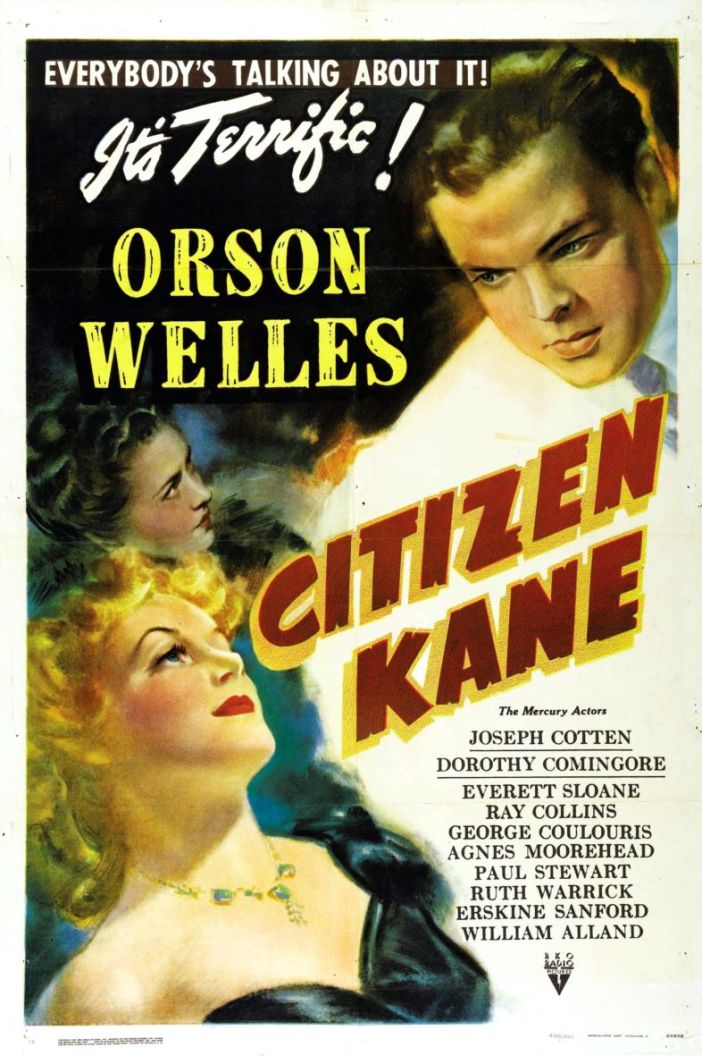

A brilliant and brazen 25-year-old makes one of cinema’s great works, and an enemy of one the most powerful people in the world. The story of Orson Welles, William Randolph Hearst, and the attempted censorship of Citizen Kane.

‘Orson Welles and Citizen Kane’ by Emil Pritt from New Masses. Vol. 38 No. 7. February 4, 1941.

The devious Mr. Hearst tries to suppress a movie. Syndicated gossip-mongering and continental wire-pulling. RKO fiddles while San Simeon burns.

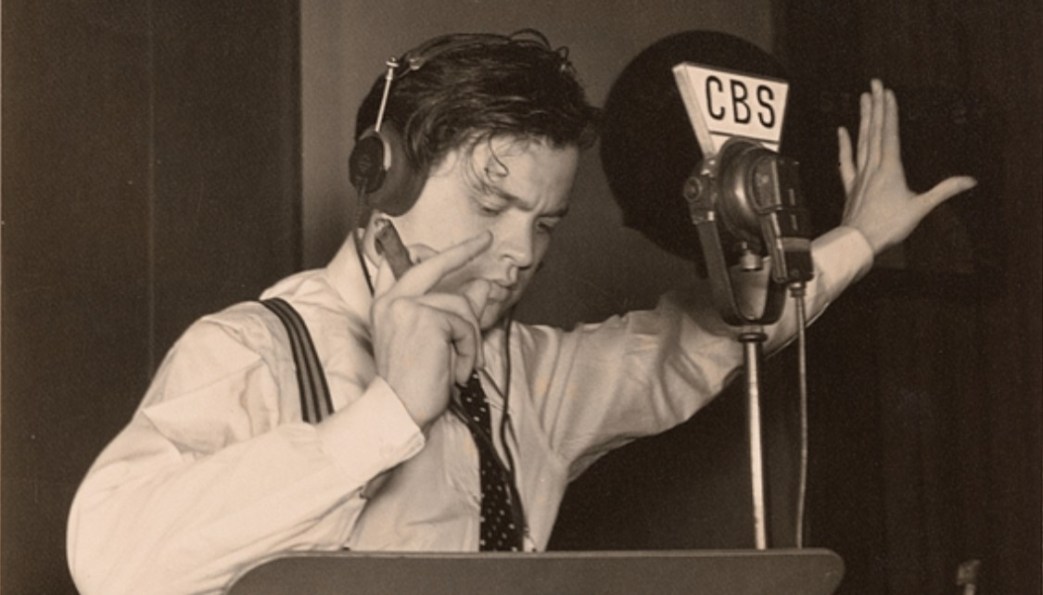

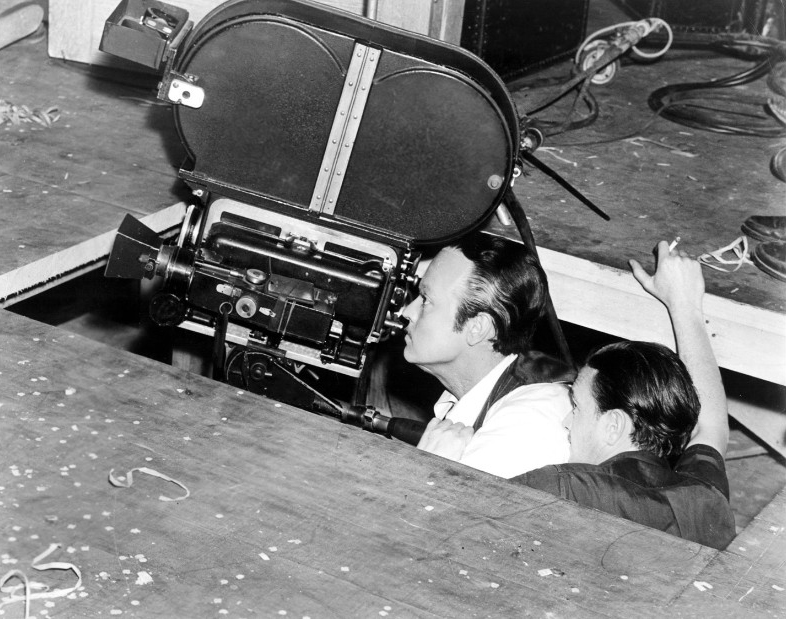

UNTIL quite recently, a lot of people in Hollywood thought that Orson Welles was just a great big beautiful publicity stunt. They knew that a young boy, five or six years old, had come from the planet Mars to Vine Street in the summer of 1939 and was given a contract at RKO studios to make three pictures. They heard vaguely that he was about to make the first picture, and then something happened to the story. They heard that he got another story, and then something happened to it. They heard that he conjured up still another story, and this one he was really making into a picture. He grew a beard and shaved it off and broke his ankle and had a radio program sponsored by soup. It was all rather fantastic and other-worldly. And then, early this year, Mr. Orson Welles and Mr. William Randolph Hearst collided head-on and everyone suddenly discovered that it was all very real.

Mr. Welles had, after a year and a half, finally completed a picture called Citizen Kane and simultaneously the Hearst publications banned all publicity from RKO. Hollywood’s elves and sprites remembered a piece in Variety six months ago that claimed that Welles’ picture was based on the rise and degeneration of Hearst, but nothing more authoritative was known. The completed film had been shown to a select few who didn’t do much talking. Everybody waited with varied degrees of impatience for the release date, which was announced as February fifteenth.

We fade to a telephone call, made on a rainy California night from Miss Hedda Hopper to Mr. Hearst. She tells him that the picture is really about him and that it tears him, with scientific and esthetic precision, into a thousand sociological and psychological shreds. Furthermore, Citizen Kane dies, a broken and beaten man.

This telephone call–as Miss Hopper undoubtedly calculated–made Mr. Hearst hit the ceiling with a vehemence any stunt man could envy. He gathered himself together after the initial explosion and got hold of Miss Louella Parsons, his Ambassador to Hollywood and Miss Hopper’s greatest rival at syndicated gossip-mongering. After wiping up the floor with her, Hearst ordered Miss Parsons to lay the groundwork for an attack. No one was going to portray him with such disrespect, and no one was going to dare show Mr. Hearst dying. Death is verboten in San Simeon.

The next day Miss Parsons, flanked by Hearst legal counsel, stomped into a projection room and saw Citizen Kane. Mr. Welles sat with her, but neither spoke. When the picture was over, she stomped out and the battle was on. A color photograph of Ginger Rogers was pulled out of the magazine section of Mr. Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner and the Hearst press throughout the nation received strict orders to ban all RKO publicity. In New York Mr. George Schaefer, president of RKO, received a telephone call from Miss Parsons asking him not to release the picture if he didn’t want a peck of trouble from Hearst. But Schaefer was in one of those peculiar positions that compelled him to announce that Citizen Kane would be released as scheduled. He had gone out on the limb in defending Welles against the attacks of his Board of Directors and the petty attempts at sabotage in the studio. And so now he found himself solely responsible for an $800,000 investment. Mr. Schaefer isn’t a man to ask for trouble and yet he isn’t able to throw away almost a million dollars, which is to say that this was a hell of a fix.

So long as the pressure on him was exerted only by Hearst, however, Schaefer held comparatively firm. He arranged that all plans for exploiting the picture go on as projected and he took great pains to make certain that the issue would remain quiet and isolated. Perhaps it would just dry up and blow away. Perhaps Hearst might do the same. But Mr. Schaefer was fiddling while San Simeon burned. Hearst was in no mood for drying up and blowing away: he was out to see the negative of Citizen Kane destroyed and he would pull all the tricks out of his hat to gain this end.

In Hollywood you gradually began to hear the phrase “skeleton in the closet” repeated with increasing frequency. Every producer in town, apparently, has one or more of such skeletons. Mr. Hearst, the sly old fox, knows where all the closets are. Suppose he should say to Louis B. Mayer, “I wouldn’t like to publish all I know about you, but I may have to do just that if this picture gets released.” Mr. Louis B. Mayer would probably faint. It may seem quite unbelievable, but the rumors say that that’s just what he did. Fainted dead away. When he came to and gathered a little strength, he got hold of George Schaefer on the other side of the continent and told him that it would be an unwise thing–and perhaps unpatriotic–to let anyone in the world see Citizen Kane. Mr. Jack Warner said the same thing. And so did Mr. David Sarnoff, who is a very big man in the entertainment world; he sits, among other places, on the Board of Directors of RKO; and he too would seem to have a closetful.

Mr. George Schaefer was getting more upset every day. After all, the producers couldn’t be disregarded completely: they are important men in an important industry. They like to think that a blow to them is a blow to all Hollywood. Mr. Schaefer’s nervousness began to manifest itself in repeated transcontinental calls to Orson Welles. Hold tight, he would say. Yes sir, Orson would reply. I’m going ahead with the advertising campaign, he would say. Great, Orson would reply. You haven’t shown anyone the picture, have you? he would ask. Oh no, Orson would reply.

This sort of thing went on and on. Welles himself was in the awkward position of wanting to defend the man who had given him such good treatment, but at the same time wanting to get the picture out to the public. He wasn’t allowed to say anything, to make any outspoken stand against Hearst. Schaefer’s sad predicament was producing a state of high tension all over town. Welles stoutly maintained that the picture was not about Hearst but about a type of capitalist. Lawyers for both Hearst and RKO declared that there was no basis for any kind of suit whatever.

All of which simply raised Hearst’s temperature several degrees more. Then it began to get out that Hearst was concentrating an attack on Nelson Rockefeller. Such an attack, together with the flank movements through the closets, would most certainly raise a stench which could easily be appreciated as far up as Mr. Welles’s planet Mars. Mr. Nelson Rockefeller has been charged by President Roosevelt with the task of “promoting closer relations and better understanding between the American republics.” One phase of this broad program is the responsibility of the movies. John Hay Whitney is working under Rockefeller to coordinate Hollywood’s effort. Prominent on the committee that Rockefeller appointed to work with Mr. Whitney are Louis B. Mayer, Harry Warner, and George Schaefer. And so, by this very circuitous attack, Hearst attempted to strengthen his entire campaign.

It can be seen, then, how one man’s effort to censor production in Hollywood might be successful. Through an intricate process (referred to by the wise boys as two parts blackmail and one part doddering frenzy), Hearst is in effect trying to prove that Citizen Kane is a disruptive force tending to destroy national unity, imperil the defense program, and outrage relations between this country and South America. He also says, incidentally, that he himself is being grossly maligned. All the stops are being pulled out. Even Welles’ well-wishers in Hollywood’s top jobs and executive offices are saying that Hearst has mapped out a neatly vicious program that can’t very easily be disregarded; and although they’d like to see Citizen Kane get out to the public, there’s really nothing they can do. It would be ridiculous, they say, to raise the question of Hearstian censorship of the movies. For the producers, such a question is purely academic in this instance. As far as they’re concerned, a grave mistake has been made and must be corrected.

That mistake was bringing Orson Welles to Hollywood. It was known that Orson Welles had too many ideas of his own; it was known that his sympathies were with the opponents of either alien or native fascism. To bring such a man into a studio and give him a free hand was to court disaster. And if the result has been a picture which displeases Mr. Hearst, it’s only what might have been expected. Throw him to the MGM lions. So say the Hearst stooges.

But what of the others-what of the writers and directors and actors, what of the guys on the back lot, what of the millions who make up the movie audience? They certainly can’t be satisfied with any dictum of Hearst’s, and they most surely resent the suppression of any honest and valuable picture made in Hollywood. The case of Orson Welles and Citizen Kane must not be judged by a frightened or conniving Hollywood autocracy but by the people who pay the admissions; not by the Jew-baiting, Red-baiting studio vigilantes but by those who carry the weight of the little golden calf labeled Box Office; not by a bellowing old tyrant but by those ultimately responsible for having made the movies a mass entertainment. Theirs, as always, will be the final verdict.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

For PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1941/v38n07-feb-04-1941-NM.pdf