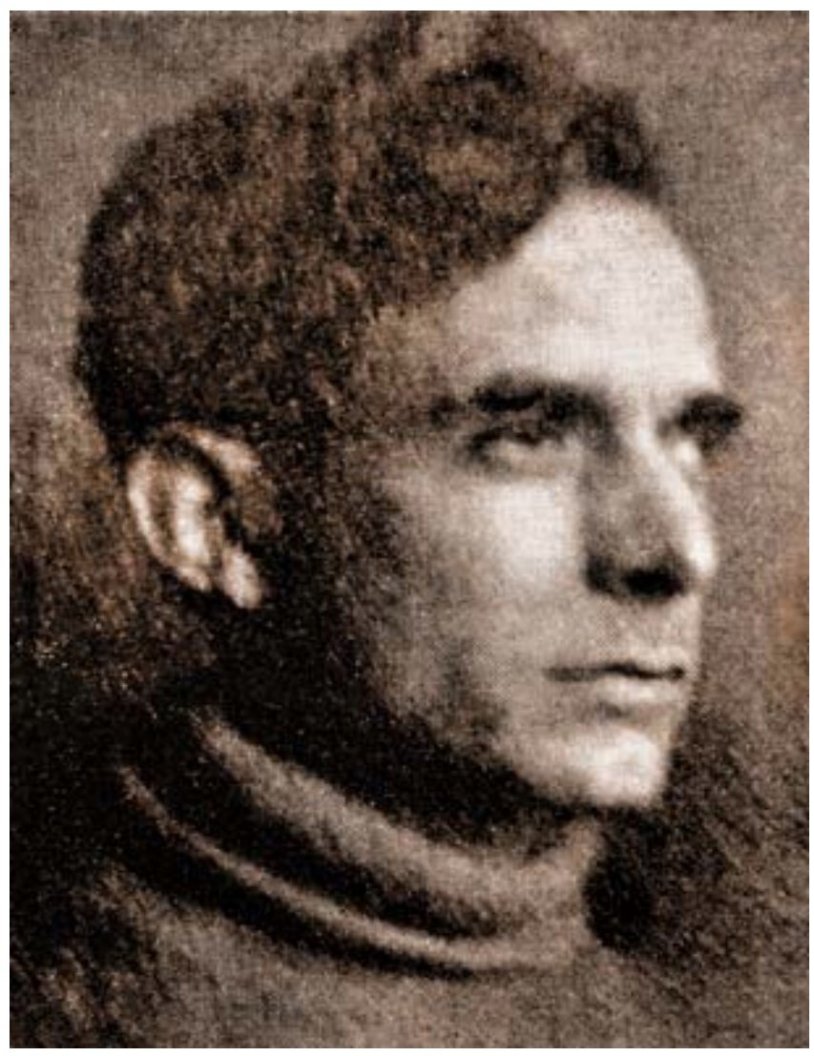

At the center of a Left Wing coalescing in the Socialist Party during the spring of 1919, Louis C. Fraina develops his analysis of the core differences in approach and understanding between the Rights, Moderates, and Lefts as the Party headed towards its fracturing that summer.

‘The Left Wing and the Revolution’ by Louis C. Fraina from The New York Communist. Vol. 1 No. 2. April 26, 1919.

THE distinguishing feature of the controversy in the Socialist Party between the Right Wing and the Left Wing, between the moderates and the revolutionists, is that the Right Wing refuses to develop and defend its real program. This is partly fear, partly camouflage, and partly sheer stupidity.

The moderates have a program, and a consistent It consists of parliamentarism, of reprogram. forming Capitalism out of existence, of municipalization and nationalization of industry on the basis of the bourgeois parliamentary state, of the theory that the coming of Socialism is the concern of all the classes, in short, the policy of the moderates (which is in itself consistent, while inconsistent with fundamental Socialism) is a policy of petit bourgeois, “liberal” State Capitalism. But this policy broke down miserably under the test of the great crisis of Imperialism; it broke down under the test of the proletarian revolution, and revealed itself as fundamentally counter-revolutionary.

But the moderates, essentially, still cling to this reactionary policy, although they are compelled by circumstances to disguise it, to camouflage it with cheap talk about “being left wing” and “a shift to the left” in the international movement, compelled to wait until “normal” times in order openly to defend their reactionary policy. So the moderates refuse to discuss the fundamentals of the Left Wing Manifesto and Program; they refuse to oppose their real policy to ours; they dare not.

Accordingly, the Right Wing indulges either in vituperation of our revolutionary comrades, in threats of expulsion (guardians of the unity of the Party!), or in sophistry.

Characteristic of this sophistry was Algernon Lee’s letter in the Call of April 2nd Lee implies that the acceptance of the Left Wing policy depends upon an actual revolutionary crisis, and says:

“Have we reason to expect a revolutionary crisis in this country in the proximate future, aside from the possibility of such a crisis being voluntarily precipitated by one element or another?

“In such a crisis, if it should be precipitated (no matter by whom) would the majority of the people probably be actively with us or against us? Or would the majority remain neutral and inert, ready to accept the outcome of the combat between a revolutionary minority and a reactionary minority? latter case, taking into account only the supposed active minorities, which of them would probably I win in a decisive struggle at this time? On the basis of our answers to these questions, have we reason to seek or welcome a hastening of the crisis?

“These are fundamental questions. Upon the answers we give to them must rest our decision on detailed problems of methods and tactics. They are unescapable questions.”

It is important to understand the immediate “moment” in the great social struggle as a basis for action; but Lee uses it to make arguments against action.

The policy of the Left Wing, in general, which is the policy of revolutionary Socialism, is not a policy only for an actual revolutionary crisis. The tactics of the class struggle, of the unrelenting antagonism on all issues between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, function in “normal” as well as in “revolutionary” times.

It didn’t require an actual revolutionary crisis to oppose the imperialistic war.

It didn’t require a revolutionary crisis to make Lee’s acceptance of the war “in order to save the Russian Revolution” a betrayal of Socialism.

It didn’t require a revolutionary crisis to make Lee’s voting for Liberty Bonds, a betrayal of Socialist practice.

It didn’t require a revolutionary crisis to make Lee’s voting for a “Liberty Arch,” on which is inscribed “Murmansk” as a glory of the American troops, a betrayal of the international proletarian revolution in general, and the Soviet Republic in particular.

It doesn’t require a revolutionary crisis to condemn the policy of petty-bourgeois reformism and compromise pursued by Algernon Lee and his confreres in the Board of Aldermen.

And it doesn’t require an actual or immediate revolutionary crisis to accept the Manifesto and Program of the Left Wing; but this acceptance is necessary for the immediate struggle of the moment, and as a preparation of our forces for the revolutionary struggle that is coming.

Let us discuss this problem more fully. It is necessary to completely expose the miserable arguments of the Right.

The central concepts of Left Wing theory and practice are mass action and proletarian dictatorship. From these concepts flow three sets of tactics: before, during and after the Revolution. The immediate “moment” in the social struggle may compel a different emphasis; but the tactics are a unity, adaptable to the particular requirements of the social struggle.

Mass action implies the end of the exclusive concentration on parliamentary tactics. It implies awakening the industrial proletariat to action, the bringing of mass proletarian pressure upon the capitalist state to accomplish our purposes. It means shifting the centre of our activity from the parliaments to the shops and the streets, making our parliamentary activity simply a phase of mass action, until the actual revolution compels us completely to abandon parliamentarism. Mass action has its phases. It isn’t necessary to have an actual revolution in order to use mass action, before the final form of mass action we may use its preliminary forms, in which, however, the final form is potential. Take, for example, our class war prisoners. It is necessary to compel their liberation. The Right Wing depends upon appeals to the Government which has imprisoned our comrades, upon liberal public opinion, upon co-operation with bourgeois and essentially reactionary organizations in “Amnesty” conventions, upon every thing except the aggressive mass effort of the proletariat. The Left Wing proposes a mass political strike to compel the liberation of our imprisoned comrades, to bring proletarian pressure upon the Government. Get the workers to down tools in the shops, march to other shops to pull out the workers there, get out in the streets in mass demonstrations, that is mass action we can use now, whether or not we are in an actual revolutionary crisis.

In proletarian dictatorship is implied the necessity of overthrowing the political parliamentary state, and after the conquest of power organizing a new proletarian state of the organized producers, of the federated Soviets. These concepts were implied (if not fully expressed) in revolutionary industrial unionism, which equally contained in itself the implication of mass action. Revolutionary industrial unionism placed parliamentarism in its proper perspective. The acceptance of and the propaganda for revolutionary industrial unionism did not require an actual revolutionary crisis: yet the moderates refused to accept this vital American contribution to revolutionary theory and practice (even refused to accept industrial unionism as necessary in the immediate economic struggle.

No! It is miserable sophistry to affirm that the Left Wing policy accords only with an actual revolution. That is precisely what the moderates in Europe said. When the war broke, the moderates (led by Scheidemann, Cunow, Plekhanov and Kautsky), declared that the Basel Manifesto had proved wrong in expecting an immediate revolution, that the masses had abandoned Socialism, therefore— they had to support an imperialistic war! But the Basel Manifesto did not assume an immediate revolution; it asserted that war would bring an economic and social crisis, and that Socialism should use this crisis to hasten the coming of revolutionary action.

The moderates in Germany said it was absurd to expect a revolution; and then they used all their power to prevent a revolution. And when the proletarian revolution loosed itself in action, the moderates acted consistently and ferociously against the revolutionary proletariat.

In Russia, the moderates said a proletarian revolution was impossible; but when it came, they acted against the revolution.

That is the attitude of the moderate Socialists everywhere, who are riveted with chains of iron to the bourgeois parliamentary state, who are absorbed in futile petty bourgeois reformism and the “gradual penetration of Socialism into Capitalism.” Their arguments may appear plausible, until the test of the proletarian revolution reveals them as sophistry. Lee’s arguments and policy are characteristic of the Scheidemanns, the Hendersons and the Vanderveldes…

Imperialism, roughly, appeared in 1900; and with its appearance developed the revolt against parliamentary Socialism–Syndicalism, Industrial Unionism, Mass Action, Bolshevism, the Left Wing. Imperialism, as the final stage of Capitalism, objectively introduced the Social-Revolutionary epoch.

But the dominant moderate Socialism did not adapt its practice to the new requirements; and it broke down miserably under the test of the war and of the proletarian revolution.

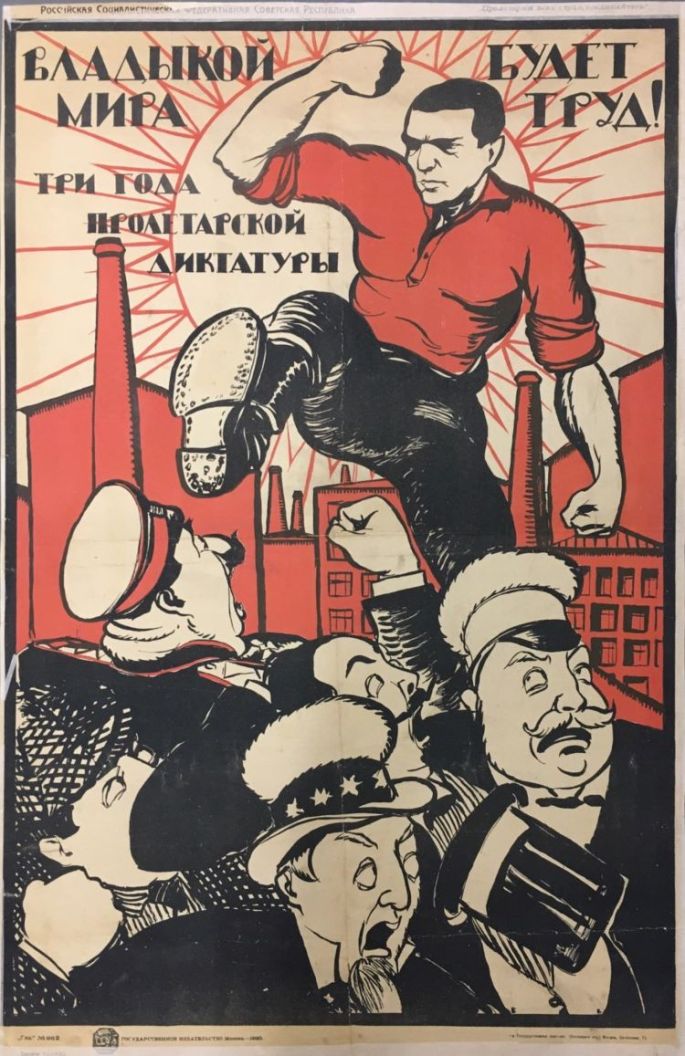

The war was the expression of the economic contradictions of Capitalism, of the insoluble problems of Imperialism. It is clear that Capitalism is breaking down; that the proletarian revolution is conquering. Capitalism cannot adjust itself to the new conditions, cannot solve its enormous economic problems. The world of Capitalism is in a revolutionary crisis, more acute in Europe, less acute in the United States, but still a crisis This crisis, which is a consequence of the economic collapse of Capitalism, provides the opportunity for Socialism to marshal the iron battalions of the proletariat for action and the conquest of power.

The final struggle against Capitalism is on; it may last months, or years, or tens of year this is a revolutionary epoch imposing revolutionary tactics. And revolutionary agitation is itself an act of revolution.

It is not our job to “hasten” a revolutionary crisis. Capitalism itself takes care of that. job is to prepare. Our job is to act on the immediate problems-unemployment, the soldiers, strikes, class war prisoners—in the spirit of revolutionary Socialism, in this way preparing the final action.

The Left Wing Program is a program of action, not a program of wishing for the moon. Sophistry can’t annihilate it. Life itself is with us.

The New York Communist began in April, 1919 as John Reed’s pioneering Communist paper published weekly by the city’s Left Wing Sections of the Socialist Party as different tendencies fought for position in the attempt to create a new, unified Communist Party. The paper began in a split in the Louis Fraina published Revolutionary Age. Edited by John Reed, with Eadmomn MacAlpine, Bertram Wolfe, Maximilian Cohen, until Reed resigned and left for Russia when Ben Gitlow took over. In June, 1921 it merged with Louis Fraina’s The Revolutionary Age after the expulsion of the Left Wing from the Socialist Party to form The Communist (one of many papers of the time with that name).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thecommunist/thecommunist1/v1n02-apr-26-1919-NY-communist.pdf