Ellen Wetherell describes worker organizing and conditions in the Washington Bureau of Printing and Engraving, where the U.S. government makes stamps and money. This revealing look declares the workplace as ‘worse than a Southern textile mill.’

‘Uncle Sam’s Wage Slaves at Work’ by Ellen Wetherell from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 13 No. 1. July, 1912.

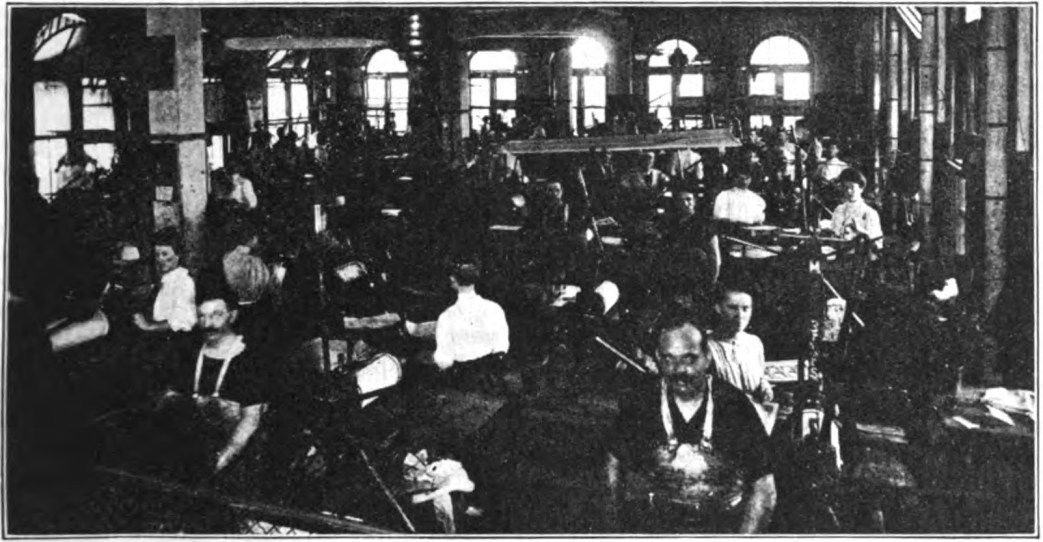

ON the dank, unwashed floors of the great press room of the Government Department of “Bureau of Printing and Engraving” at Washington, there are deep depressions made by the toiling footsteps of the women wage-slaves as they move forward and backward in a steady, monotonous tread about the presses at their work as “Printer’s Assistants.” The men and women in this room are employed by the United States Government to make its paper money. There are windows on one side of the room, but the light is insufficient, therefore over each printing press there are electric burners whose heat adds to the close, depressing air in which oil, ink, and foul dust, mingle with the breath and sweat from the bodies of seven hundred men and women at work.

The clothes worn by the printers are caked with ink, while the dresses of the women drip with grease which flies from the presses in their revolutions. А girl’s dress is ruined by a day’s wear. Said one union woman worker to me, “We went to Superintendent Ralph and asked if shields of zinc or-some other substance, could not be placed around the presses to protect the clothes of the women.’ With a satirical smile he replied, ‘Oh yes, a bow of pink ribbon on every press if you say so.’”

Two years ago Alice Roosevelt with other society women declared they wished to “о some good.” They said they wanted to help improve the sanitary condition at the “Bureau” and to “make the girls happy in their work.” One day they drove down. Mr. Ralph knew of their intended visit and was ready for them. In the new wing of the building a dressing room was made—clean and fine–that these idle dames of society might see for themselves how well the government at Washington treats its workers. These ladies were not shown any of the workrooms; nor did they see the dressing rooms in actual use.

Last week, following a guide, I went through the Bureau; I stood upon an elevated platform in the press room where, as the guide said, “You can get a better view of the place.” What I saw was a long, low room having a dozen windows or less. An open iron grating higher than the head of the tallest man there, encircled all sides. Within this grating I saw a mass of men, and women, and machines so closely huddled together that it would have been dangerous for a visitor to have attempted to move around among them. The noise of the presses drowned our speech, but a wo. man from the open spaces of the far west who stood beside me, shouted in my ear, “How awful.” Then, probably apologetic for her government, she added, “But these men and women work only four hours a day.” “You are mistaken, madam,” I called back, “government workers here go on duty at eight o’clock in the morning; they have half an hour at noon for lunch, and quit work at. half past four at night, and for these hours of laborious toil the women receive $1.50 a day.”

There is a night force at work in the “Bureau” and on this force over 200 women are employed. Said one pale faced worker to me, “I prefer to work at night. Of course I get no evenings for recreation of any kind, but at night the Bureau is less crowded; the air. is better, and I am not so tired; I get home at midnight.

Alice Roosevelt said that the Bureau of Printing and Engraving was no place for a woman to work, but she did not say by what means the dependent Bureau girls were to make a living. We have all heard of the ingenious remark of that famous French queen, when told at the time of the Revolution that the people were starving for bread. “But why do they not eat cake?” This is the logic of the idle rich.

Most of the workers in the Bureau eat their lunches in the building. “They bring them and put them in the lockers provided for their clothes. Every man and woman in the press room is compelled to make a complete change of clothing before they go home. Said one girl, “The lockers are but eighteen inches long and into this go my dirty clothes, my dirty shoes, and my lunch, when we shake our clothes at night, red ants and mice run from them in all directions.”

The dressing rooms of the Bureau workers are taken care of by charwomen, but they are never clean. If a girl wants her locker to be decent she must scrub it herself. Six towels are allowed for 200 women.

The superintendent of the Bureau claims that the women workers receive sufficient wages, but strange to say, the women think differently. Three years ago a handful of Bureau women came together to talk union. The printers were willing to assist them in organizing. Mr. Ralph said he had no objection, but the idea seemed to worry him. Later some 300 women rallied to the organization under the A.F. of L. The union held meetings every two weeks. Frank Morrison spoke for the women and urged them to petition for a fifty-cent increase in wage, but his talk seemed half-hearted. Scant was the help the union got from the national body, and although the headquarters of the National A.F. of L. is located in Washington, and Mr. Gompers and Morrison are well aware of the work conditions at the Bureau, and the low wages of the women, nothing has been done to substantially aid these government exploited wage-slaves in their dire distress.

United States government workers in Washington cannot strike, they cannot vote, neither can they petition congress save through the man next higher in power.

It was by the help of a young Socialist, some three years ago, and the determination of the union Bureau girls themselves, that twenty-five cents increase in wages per day for the women beginning their apprenticeship in the department, was wrung from Ralph.

Superintendent Ralph boasts of his power to cut down expenses on behalf of the government. In 1910 he claimed that from the appropriation made that year, he turned back into the treasury, $500,000. Today the union of “Bureau girls” is at low ebb. I am told that those girls who have a married life in view are not friendly to the union. But there are good union women, and good stuff to make class union women, among the 2,000 workers in the Bureau.

Boys over sixteen are employed as printer’s assistants, but they are clumsy compared with the girls. To the well drilled girl, the work has become an art, and the printer who has become accustomed to his assistant’s method of work likes to retain her in his employ. Printer’s assistants receive $1.25 per day from the printer, and twenty-five cents from the government—the printers claimed that the raise in wages for the girls must come from the government.

There are printer’s assistants who can handle 1,000 sheets of bills a day, while 500 IS a big day’s work for a boy.

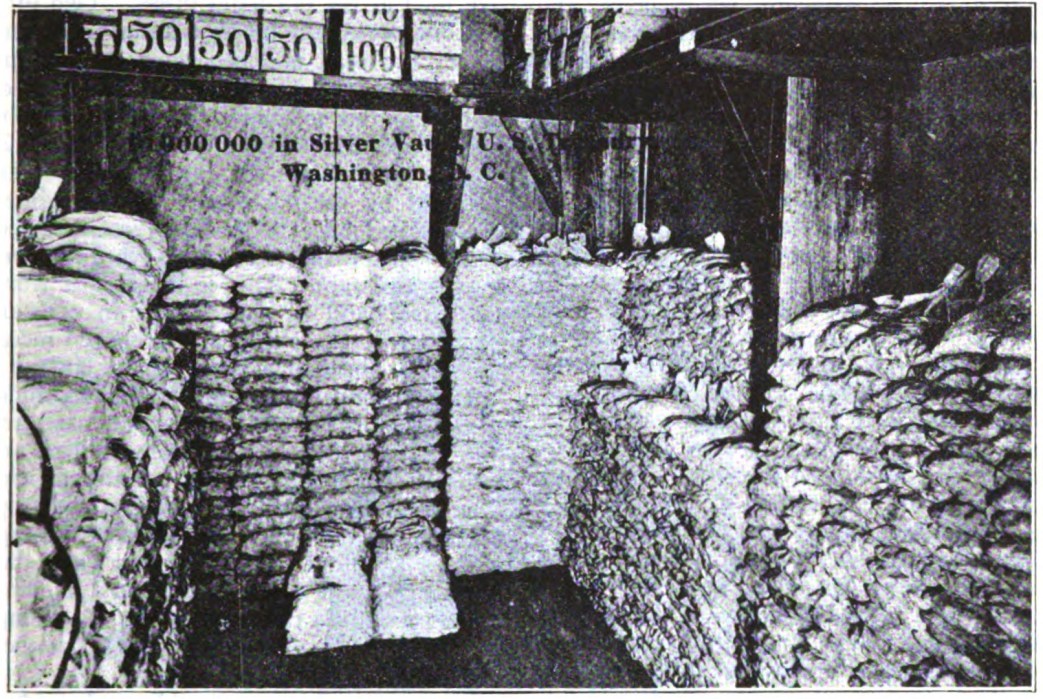

The printed sheets of money usually contain eight bills ranging in denomination: from $1.00 to $10,000; the presses register the number of sheets printed.

A printer’s assistant takes a blank sheet of paper which has been wet with water to make it pliable, and lays it on the press made ready with chemicals by the printer, then by a most laborious effort of his body and arms the printer turns the revolving press once. The assistant is alert to take the stamped sheet from the engraved plates and to lay on another wet one; to do this she is compelled to step backward to a table for the wet sheet, then forward to the press, and so on for eight hours.

There are no seats for these women to drop into even for a moment. They are always moving forward and backward, first with the wet paper, then with the printed bill, amid a confusing noise of machinery, dirt and grease.

I have been through the notorious cotton mills of South Carolina. I have stood with the workers at the machines in the great shoe factories of Massachusetts, I know what it is to work, and breathe the phosphorous laden air in the Corporation match factories of the north, but I have yet to find a more congested, or foul workshop than that of the great press room at the Government Bureau of Printing & Engraving at Washington. An expert shoe stitcher can command $12 to $20 a week, the Government Bureau women are obliged to live, and pay for food, housing, and clothes, on a $9 wage a week. Let those Socialists who are clamoring for “Government Ownership” study the work conditions of those industries in Washington over which the stars and stripes wave so proudly; let them talk with these government wage-slaves and hear from their own lips, if they can, how fine a thing it is to work for the United States Government.

A bank note is not finished in the press room, but it has to pass through the hands of 54 persons and 20 machines before it becomes United States money. A printer is allowed to spoil one sheet in every one hundred, but if the sheet is lost the printer is obliged to pay the face value of the note.

The printing of bills is done by hand presses. The printers claim that the work done by the hand press is of a superior finish over that done by the power press. Superintendent Ralph favors power presses. It is said that he is to receive a bonus on each press introduced into the Bureau; we know that he was urgent at the late hearing before the Congressional Committee to prove that the power press is an improvement in every way over the hand press, “And there is the economy to the government,” he pleaded. But Ralph said nothing about the money he may put into his pocket by the introduction of power presses into the Bureau and the discharge of a large number of printers and their assistants. Of course the printers are against the power press; the printer’s union took action on this matter at the hearing, but as the Evolution of Industry takes no account of the individual, neither does the capitalist, nor the capitalist government. There was a compromise, and a small number of power presses are to be placed in the Bureau.

The Glass Blowers claimed that never a machine could be invented to displace their high grade hand labor. They were kings of their craft, but, Evolution, “so careful of the type is she, so careless of the single man,” produced a glass blowing machine which enabled six men to do the work of six hundred. No man or woman wishes to see the bread taken from their mouths—none is willing to starve for the sake of scientific development of machinery, and the plate-printers and their assistants in the Bureau of Printing & Engraving are no royal exception.

I was taken into the room where postage stamps are made, and into the revenue stamp room. The latter room contains a new power press invented by Superintendent Ralph; this press does the work of five men at the old hand press. Two girls run one press; the machine numbers, trims, places the seal, and separates the stamps. One million sheets of stamps were spoiled in testing this machine. There are revolving presses for printing postage stamps, 24 stamps on a sheet; the engraved plates are polished by the bare hand of the printer, each plate must be polished as it comes around after the sheet has been removed by the assistant. This is dangerous work, the bare hand of the printer in constant contact with the chemically prepared metal. Only one sheet at a time can be laid on a postage stamp press. A sheet slides under a roller, this is removed by an assistant, and the engraved plate again rubbed and polished by the bare palm of the printer. One press can print 4,000 sheets of stamps a day. There are 30,000,000 postage stamps sent out of the Bureau each day.

The noise made by the presses is deafening.

I passed on into the room where the stamps are examined and counted. A girl expert can count 15,000 stamps a day.

About to leave the building, I said to the guide: “There is one room we have not seen,” the “Sizing Room.” The woman’s answer came quick, “I cannot take you into that room.”

Capitalism is stronger than the craft unions. We need class unionism for government wage-slaves as well as for corporation wage-slaves. The evolution of the machine is driving the craft union to bay. “One Big Union,” demanding for each worker the full equivalent of his or her product, this must be the program of the government employee at Washington; this is Socialism, and it is Socialism that the plate-printers will turn to ere long. Today the leaders of the craft unions are of the “Pure and Simple” kind. Said one to me, “I am a Democrat, the Democratic party first, last and always.”

Washington’s avenues are beautiful and spacious. Its trees and parks and sparkling fountains are a source of delight. Its marble buildings command the admiration of the world, but over and above these stately piles of marble, against the pale blue of the heavens, floats the stars and stripes, beneath which Liberty lies low and bleeding, and justice is but a thing of scorn.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v13n01-jul-1912-ISR-gog-ocr.pdf