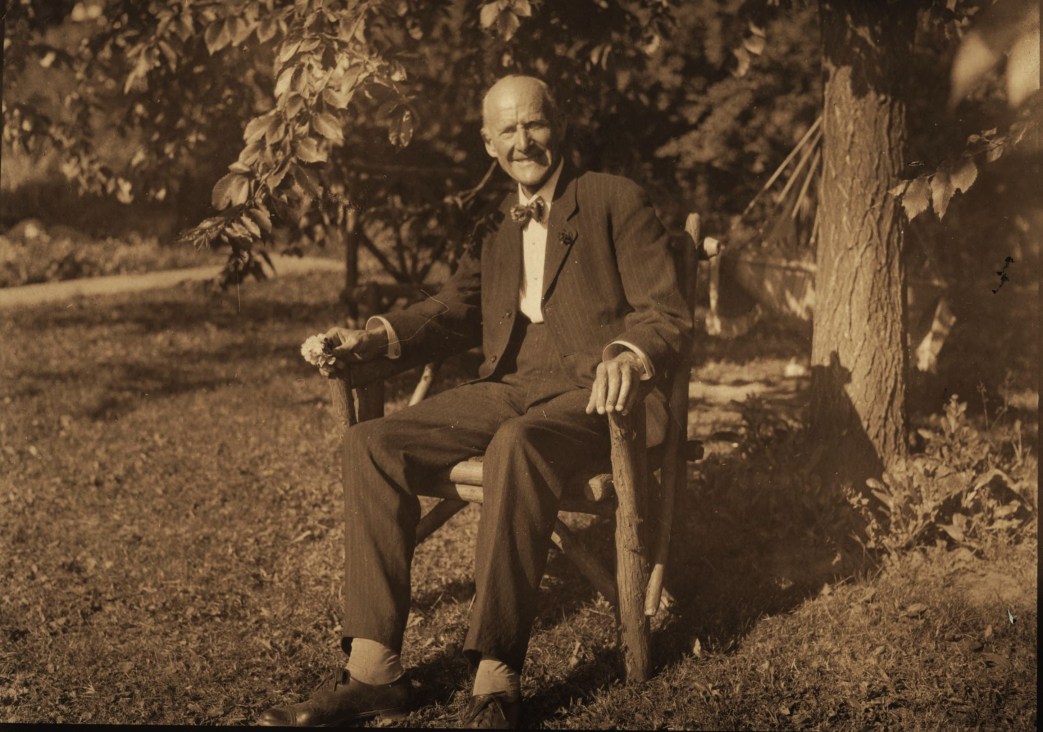

Ludwig Lore pays respects to a 63-year-old Debs on his April 13, 1919 entry into federal prison to serve ten years for sedition, contrasting his stance, and leadership role, to those of his critics in the Socialist Party’s Right Wing.

‘Eugene V. Debs, a Revolutionist’ by Ludwig Lore from Class Struggle. Vol. 3 No. 2. May, 1919.

On more than one occasion, the socialist movement of this country has paid dearly for its readiness to raise upon a pedestal men and women who possessed the gift and the ability to become its leaders. This has been particularly true where these newcomers in the socialist movement had established for themselves enviable reputations as radicals and reformers in bourgeois circles. Their coming was hailed as a great achievement, their opinions were received with a degree of attention and accorded a degree of importance entirely out of keeping with their experience in the working-class movement or their deserts. Men like Benson, Russell and others became leaders in the socialist movement, not on account of their services in the interests of the working class, but for the notoriety that attached itself to their names and to the prestige that their membership gave to the party in certain circles. And so it happened, that when the great crisis came, when the Socialist Party was forced to undergo an acid bath that separated the true metal from the alloy, that these elements in our movement failed. They were tried — and found wanting.

But our movement has leaders too that were made of sterner stuff — leaders that can take their place beside the best the international socialist movement has produced. And foremost among them all stands Eugene V. Debs. No matter how great the crisis — and the socialist movement has gone through more than one critical period — Debs always rang true. He came into the movement at a time when to be a socialist meant to be a social outcast. He came to us, not as a Messiah sent from above, to liberate the toiling masses from economic and political slavery, but as a workingman who had Lamed, in the bitter school of a capitalist jail, that the only hope of the workingman in the unequal fight against the organized capitalist class lies in the merging of his identity with that of the class-conscious proletariat. He became one of us to learn, not to teach, to serve, not to lead, to give the best that was within him, without stint and without hope of gratitude. For more than two decades he has served the Party, whenever it called him, in whatever position the movement saw fit to place him, always ready to carry his share of the burden, heavy and large though it was because of his great capacities. But wherever he stood, and in whatever capacity he served the movement, it was always as a revolutionist, as one who knows that to be a socialist means to be a rebel and a fighter, that achievement for the working-class means sacrifice. And because this is so, Debs was and is one of the men most feared, and withal most respected by the American ruling class.

Already our bourgeoisie is beginning to feel no small degree of discomfort over the victory it won over the revolutionary working-class movement when it passed a ten year sentence upon Debs. Hitherto, because of the comparative obscurity of its victims, they were able to lend color to the fiction that the men and women of the radical and socialist movements who had been sentenced to prison, had indeed endangered the interests of the nation with their propaganda. But Debs has been too long before the American public. No power on earth can make the American workingman believe that he was prepared to act dishonorably, that he would act against the interests of the American proletariat. The conviction of Debs has shown the organized campaign of frightfulness was directed, not against the enemies of the nation, but against the enemies of its exploiters.

Once more the Spargos and the Russells, the Slobodins and the gentlemen from the “Appeal to Reason,” nee “New Appeal” stand ready to serve the ruling class, the more willingly since by so doing they hope to rehabilitate their badly damaged standing in the socialist movement. They have sent out appeal after appeal to Washington and to Paris, pleading for clemency for this splendid upright man, they whose denunciations and slanders about the socialist movement and its aims are to no small degree responsible for the hatred and intolerance that prompted this campaign against the socialist movement. Nor have their appeals failed to accomplish their purpose: there have been suggestions, transparently obvious, that a sufficiently repentant Debs might reasonably hope for a pardon.

But Debs is made of sterner stuff. And neither the pleas of those who will accept government missions today and make overtures to the socialist movement tomorrow, nor the fear of ten years behind prison bars will swerve him from the path he has chosen. As Debs goes to Moundsville jail he gives his comrades a message that sends a quiver of pride through their veins:

“I shall refuse to accept a pardon unless that same pardon is extended to every man and every woman in prison under the espionage law. They must let them all out— I.W.W. and all— or I won’t come out. I want no special dispensation in my case.”

With these splendid words Debs has set us a standard that we must uphold and carry out. To accept less, to ask for less, were an insult to the man whose courage and whose cheerful readiness to endure the fullest measure of sacrifice with his comrades has struck an answering chord in the heart of every thinking man and woman in the United States. All over the country, in sunshine and in storm, socialist meetings are being attended as they were never attended before. The socialist movement stands face to face with an opportunity that holds out the greatest promise for the future of our movement if we are big enough to grasp it. Shall we be smaller, less brave than our Eugene Debs? Shall we be afraid to demand where he has spoken. Will we, too, be ready to give all, that we may win all?

The Class Struggle is considered the first pro-Bolshevik journal in the United States and began in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution. A bi-monthly often over 100 pages and published between May 1917 and November 1919, first in Boston and then in New York City by the Socialist Publication Society. Its original editors were Ludwig Lore, Louis B. Boudin, and Louis C. Fraina. The Class Struggle became the primary English-language paper of the Socialist Party’s left wing and emerging Communist movement and paid lose attention to the fight in the Socialist Party and debates within the international movement. Many Bolshevik writers and leaders first came to US militants attention through The Class Struggle, with many translated texts first appearing here. Its last issue was published by the Communist Labor Party of America.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/class-struggle/v3n2may1919.pdf