A Leadville wobbly writes on the social and economic history of that Colorado metal-mining boom town, where so much exploitation generated so much wealth.

‘Leadville: A Famous Mining Camp’ by Card No. 112357 from Industrial Pioneer. Vol. 3 No. 11. March, 1926.

Says Card No. 112357, the author of the article below, “I have never read a half true account about Leadville and have often wanted the facts compiled by the workers — so finally I attempted it myself, and found I could have written much more, if it were not for the fact that an article must not be too long for the worker’s press.” This fellow worker has found out just what the editor of Industrial Pioneer has always been saying — that workers are perfectly capable of describing the industries in which they work, and of doing it from the working class point of view. In fact they are the only ones who can do it. The more of such articles as this that are written for Industrial Pioneer, the better satisfied everybody is. ED.

Invention has gone forward a step, and by means of a newly improved ‘‘flotation process,” the low grade lead and zinc ore bodies of the Southwest are again regarded by many capitalists as the scene where much labor is to be profitably exploited in the near future. The territory around Leadville, Colorado, is rich in vast quantities of complex sulphide lead and zinc ores, suitable to proper flotation but so far unworked or piled in waste dumps while the historic battles between labor and capital raged over the mines of higher grade minerals, now nearly exhausted.

The possibility of awakening this industry from its present rather quiescent stage, makes it important, from the workers’ point of view, to learn again here from the experiences of the past, for capital is still as ruthless and as greedy as ever, and workers as much in need.

During the onward march of progress, amid great eras, construction, the expansion of industries and the building of modern cities, attention is focused upon the phenomena of the present, while the older and once famous places and events are lost sight of and drop from memory in the minds of men.

The famous mining camp of Leadville, Colorado, with its past history and present status is not known to the present generation of men, therefore the facts in this story will be of value from the viewpoint of Labor.

Many accounts and tales of early day events have been written and published by bourgeois journalists, news writers and poets, but the present writer has never yet read the history of Leadville from the standpoint of the worker. He has lived in the camp many years, and has worked in its mines and smelters and on the railroads, therefore he is qualified to give Labor’s version of its history.

The site of Leadville is picturesque in the extreme; it lies in an elevated basin (10,153 feet altitude; it is called “The Cloud City”), between the main range of the Rocky Mountains to the west and a parallel spur to the east, known as Mosquito Range. Between these two ranges and a few miles below Leadville lies a broad valley through which courses the Arkansas River, the source being 12 miles distant.

At right angles to, and running westward from Mosquito Range, are several deep gulches, and in the hills between them lie the main mineral treasure chests. This area is but 10 square miles, yet 40,000 mineral claims have been located on it and it is known as The Leadville Mining District.

As early as 1860 emigrants in covered wagons were pushing their way up the Valley of the Arkansas; prospectors and miners were panning the stream beds of the intersecting gulches for their alluvial deposits.

Gold in abundance was struck in one of these gulches (near the present site of Leadville) and it was called “California Gulch,” for it rivaled the findings in the great gold rush of California in 1849.

Thousands of pioneers and fortune seekers panned the gulches around this region and after the “diggings” seemed worked out they moved on, leaving a few prospectors in Oro City at the head of California Gulch.

In the subsequent years the hills were prospected and there followed a second ‘strike about 1878; this time it was rich silver — lead carbonate ore found “at grass roots.”

A camp was established and given the name “Leadville,” or “The Carbonate Camp,” and from a few hundred people in the spring of 1879 the population grew to 60,000 at the end of the year.

People from all corners of the earth came to this bonanza camp. With pick and shovel, with windlass and bucket, wagon loads of rich carbonate ore were dug and hauled by “bull team” to Colorado Springs, Colo. One such load sold for $30,000.

Fortunes were made in a few weeks — what scenes and activities are related! Never before nor since in the history of mining camps was this period.

No railroads within 150 miles and but one single telegraph wire connecting with the outside cities! Travel and transportation was by stage coach, bull teams and covered wagons. Here was a condition where for once all had equal opportunity; with but few exceptions men worked for themselves or as co-partners, and their product was their own.

Now, take note what followed! Financiers, brokers, capitalists came with a rush; syndicates were formed; companies were founded; claims were sold and resold — and stolen. Smelters were erected; mine machinery was hauled in and placed on properties, and as early as the year 1880 the camp witnessed a great labor strike — 8,000 miners downed tools and demanded more wages and better working conditions!

The strike was effective; picketing prevented the importation of strike breakers and the miners showed a spirit of solidarity. Victory for the workers seemed near.

The mine operators and business men of the town organized what they called “A Committee of Safety” — “Vigilantes” would be a more correct name.

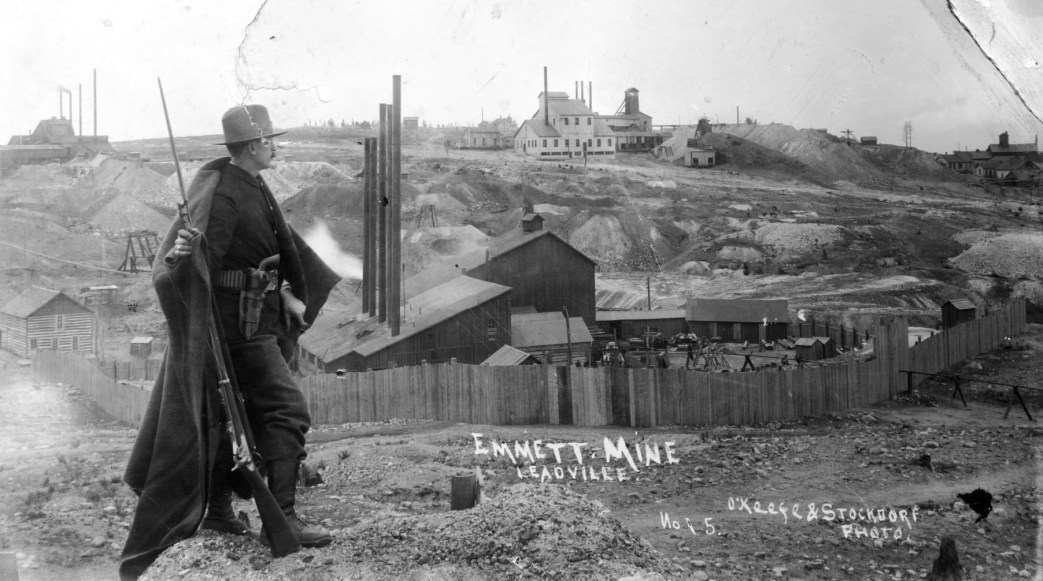

Arms and ammunition were brought into the camp and thousands were armed by this class in opposition to the miners who paraded the streets to show their Union strength. Spies and agents, provocateurs were placed among the strikers to stir up trouble, and as a last resort Leadville was put under a military siege; the militia encamped here for months. This broke the morale of most strikers and they soon returned to the mines and went back to work — defeated.

Again in 1896 the miners pitted their union strength against their masters; strike breaking followed; pitched battles ensued; trouble makers and traitors infested the ranks of the workers; conspiracy again brought the militia, the ready tools of capitalism, and again the miners’ strike was lost.

In the years since then a few demands have been made by the workers of the district, but lack of the right kind of organization blocked their efforts, and nothing of importance was gained, so today there is no union of the miners or smeltermen here.

Since 1879 concentration of mining and smelter wealth has gone on apace. The mineral claims once owned by the prospectors and miners are now in the hands of corporate mining interests; the early day independent” smelters have all ceased to operate. The Guggenheim Smelter Syndicate dominate the field; their plant at Leadville used to employ 3,000 workers; today owing to the mechanicalized processes, 900 tons of ore per day are put through the furnaces by a forces of only 450 men, of whom eight per cent are low-paid Mexican labor: the wages are $2.70 low and $5 high. This smelter combine had $12,000,000 earnings in 1924.

From the Leadville hills and gulches has been dug the fabulous sum of $500,000,000 worth of metal! — few mining camps have this production record.

The oxide ore at shallow depth was first mined, then sulphide ore deposits at greater depth were encountered and mined; the area of mineralization has been extended for miles and the geology of the camp has long been charted and studied.

Here are ore bodies of millions of tons; the hills are filled with mineral resources; gold, silver, lead, zinc, copper, iron, manganese, etc. The ores are complex and need separation, concentration, and smelting. The metallurgical processes have been solved and from these resources will be dug the metals for future generations, such is the extent of mineral wealth.

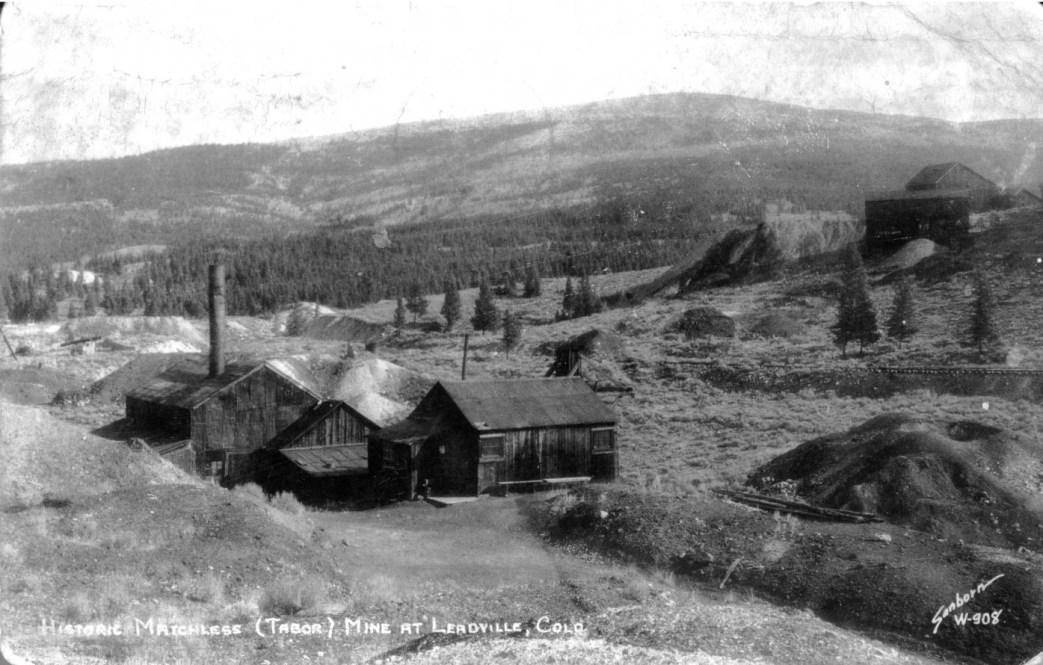

At present the population is not above 4,000, and Leadville is but the ghost of former years. The scenes have changed greatly; the hills once teeming with activity now seem deserted; hundreds of mine dumps and shaft houses and numerous smelter dumps stand as mute evidence of former life.

The landscape, once covered with evergreen Jack Pines and wildflowers and berries, is now almost barren. Civilization and poisonous smelter fumes killed off all nearby vegetation.

The gulches show great rock heaps from placer mining; old “Mother Earth” shows deep scars; mankind has often made desolate Nature’s beauty.

Not a paved street can Leadville boast! Its single walks are wooden boards, showing the wear of years, loose and rickety.

Hundreds of structures have been wrecked the last few years and the materials shipped to other points in the state for construction purposes. Scores of houses are still vacant and in a state of decay.

Few homes are modern, a sewer system serves but a small portion of the town, and the populace still empty ashes in the streets and drain waste water into the gutters.

In former years the smelting processes gave lead poisoning to the workers; the young, brawny Italian and Austrian laborers fresh from their native homes met their fate in a short time. This industrial disease or poisoning would wreck and twist their bodies, and send them to an early grave.

Human labor was a cheap commodity due to a plentiful supply — nothing was done to conserve it — no protective measures or devices were provided. Today things are better, but still detrimental to the workers’ health. The class of labor has changed with the years; Mexican labor now replaces that of Europeans.

The wage scale is as follows: Miners (machine men), $4.50 to $5 per 8 hours; muckers (helpers, etc.), $4 to $4.50 for 8 hours; pumpers, engineers, mechanics, $5 for 8 hours. This wage scale is from $1 to $2 lower per shift than in many other mining camps; conditions in these holes are generally poor and real bad in some of the mines, as there is no forced ventilation with blowers or suction fans Some shafts are 1,300 feet deep and the air is so poor a match will not light and carbide lamps burn dim.

The mining syndicate that owns and operates the Greenback Mine (one of the largest producers in the Leadville district) boast of a $17,000,000 reserve fund, yet will not install a ventilating system to furnish oxygen for the underground workers. There is a state mine inspector for Colorado, too; he has a nice office in Denver, but he should hang his head in shame — however, we know what all inspections amount to when fostered by the employer.

When all facts are compiled and the evidence given, a charge will be made against the system that wrecks men’s lives, robs them of the products of their toil and sentences their wives and children to drudgery, defaces and ruins nature’s beauty spots in the quest for profits!

Leadville becomes more intimate when the fact is shown that the foundation wealth of not a few great fortunes was made here. From 1880 to 1890 the Guggenheim Syndicate made wealth that built the smelter at Pueblo, Colo., and extended operations info old Mexico, then up into British Columbia and Alaska.

The estates of many Colorado families owe their wealth to Leadville’s hills and workers; rich residents in many other places owe their status to the same source.

The building of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad up the Arkansas Valley to Leadville and eventually beyond and over the Continental Divide, down the western slope of the Rockies and on to Salt Lake City was due to the rich ores from Leadville and the supplies into the camp assuring plenty of tonnage at a high rate per ton ($10 to $15).

It might be of some interest to know that the Santa Fe Railroad and the Denver and Rio Grande interests had open warfare to determine which could claim the Grand Canyon Route (the famous “Royal Gorge”). Cannons were placed on the rim of the canyon to hold the “grab.” Such are the peaceful and lawful methods of Capitalism!

Leadville territory, the scenic region of the Rockies, is the water shed for the valley below. This county (Lake County) derived its name from the many lakes in its hills, some of which are large bodies of water and the meccas for campers and fishermen. Twin Lakes, a beauty spot beyond compare is situated a few miles from Leadville. It was the annual camping grounds for the Ute Indian Tribe, who made regular pilgrimages to its shores, and Leadville hills and environs were their hunting grounds, before the white settlers came, after which, the Red Men lost out.

The automobile tourists, wishing to see the wonders of the Rocky Mountains, will soon be shunted through this country; its scenic beauty will captivate the eye, and its camping grounds will be long remembered.

Do not for a moment think, though, that natural beauty is what we rely upon to bring Leadville back on the industrial map. The reason why the hills will soon be riddled as never before, is a human invention, the process by which certain ores, difficult to separate on “tables” (that is by the method of shaking and washing the broken rock, to catch the lead and zinc when it sinks) are now to be made use of by floating the metal (lead, too, however heavy) up away from the ordinary rock on small bubbles of oil, which is mixed with other substances, and churned around with the ground-up rock dust that contains metal. Up to recent times the floatation scheme was not perfected in a form that would work exactly well on the particular ores around Leadville, though it was used elsewhere. Now this difficulty has been removed, and there will surely set in a long, continuous revival of industry in this town; not immediately, but as the new mills for grinding and floating the minerals are created.

A large new floatation mill is about completed and ready to start in a few days — its successful efforts will be followed by the building of more mills to treat the complex sulphide ores of which there is a vast tonnage. So, if delegates remember this, we will be abreast of the times and when the workers come into Colorado’s mining districts — the Industrial Union propaganda will give them basic facts.

Today, however, Leadville reminds one of a man who has been robbed and stripped of his wealth, left in dire need! Of the many who gathered the riches from its hills few have left any improvements.

A late senator from this district has erected a statue of the noble “Burro” — the prospectors’ pal — but this statute graces Washington, D.C., not historic Leadville!

Of the many brave hearts and spirits that once lived here, few remain — the present workers seem doped and submit to standards and wages scarcely above the level of Asiatics. Perhaps their particular brand of religion or the “white mule beverages” lull them to sleep, but whatever the reason may be — shame on labor of this caliber — it goes down to early graves — unhonored and unsung!

Come to Leadville, you rebel workers! Mexican fellow-workers have much to do here in the way of education and organization, so that these workers can demand more than $2.70 for their labor power. These Mexican men should get inspiration from the solidarity and recent gains made by their fellows down in Tampico and in Mexico throughout.

Poets have penned the grandeur of these hoary old mountains — have pictured the shady nooks.

I have mentioned the exploits of rapacious capitalism — the arch-enemy of all who toil, the stealer of wealth and the instigator of crime.

Labor has suffered ignominious defeat before this monster — but in its struggles and experiences labor is learning how to fight intelligently and is organizing its members under the plan and structure of Industrial Unionism and will some day march to victory against the class and the system that takes the products of its toil.

The Industrial Pioneer was published monthly by Industrial Workers of the World’s General Executive Board in Chicago from 1921 to 1926 taking over from One Big Union Monthly when its editor, John Sandgren, was replaced for his anti-Communism, alienating the non-Communist majority of IWW. The Industrial Pioneer declined after the 1924 split in the IWW, in part over centralization and adherence to the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU) and ceased in 1926.

PDF of full issue (large cumulative file): https://archive.org/download/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_007/case_hd_8055_i4_r67_box_007.pdf