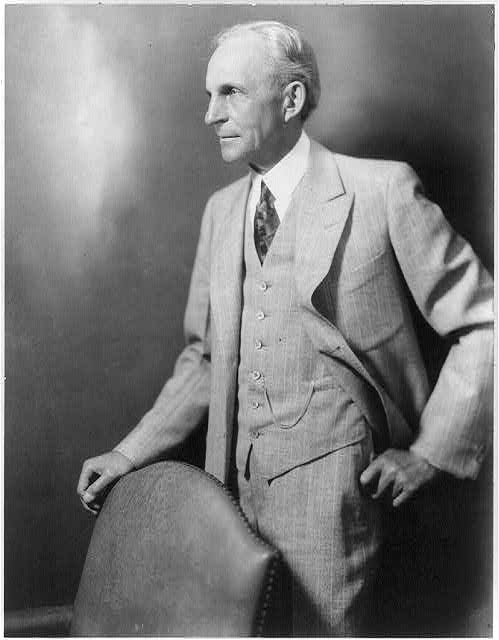

Reviled by the labor movement of the 1930s, the ghoul that was Henry Ford has been re-covered and protected by myth so that he may haunt us still. Robert L. Cruden, a former Ford line worker and fellow with the Labor Research Association, with an early expose of the ‘Mussolini of Highland Park’ written shortly after the Dearborn Massacre in which Ford’s thugs killed five workers demonstrating against unemployment.

‘The End of the Ford Myth’ by Robert L. Cruden. International Pamphlets No. 24. International Publishers, New York. 1932.

The Ford Myth has been washed away in blood. The legend of high wages, good conditions, contented workers, was riddled by the bullets which killed four unemployed workers and wounded over a score on March 7, 1932. Now the world knows that all this talk of Ford’s paternal interest in his workers is the sheerest hypocrisy, built up by his own publicity agents and dished out by the capitalist press.

But for Ford workers the Ford myth exploded years ago. Workers far from the Ford plant might be misled by the unending stream of bunk emanating from the Ford publicity department. We who have worked for Ford long ago learned, by bitter first-hand experience, what the Ford policy means in action. Driven at an inhuman pace by foremen picked for their brutality, and kicked out when we slowed up; shifted to other departments at a lower salary, or fired and then rehired at the lower wage, while the Ford publicity men blared forth “no wage-cuts”; at the mercy of the armed Ford guards and secret service men with power to fire any worker instantly whose walk or talk or look any of them found displeasing; our work-week cut at the expense of our pay envelopes, and then driven to produce the same amount of work in the fewer hours; our “week” of work cut to three days, then to two or one; now most of us long out of work altogether, waiting day after day for those long-promised jobs; standing hour after hour at the Ford plant gate, under the arrogant and brutal surveillance of Ford’s servicemen, shoved around and bullied, beaten up or slugged if we dare talk back. Such is the famous Ford policy as we auto workers get it.

Plenty Speed—Plenty Accidents

Let me tell you the story in more detail. When, in 1926, the five-day week was introduced in Ford plants, people were told the workers were to receive six days’ pay when they had produced six days’ work in five. As late as 1928, Ford was saying, “We will stick to the five-day week for employees. That schedule on the old six-day basis of pay is working out splendidly.” As a matter of fact at the time Ford was making such statements, wages were being cut throughout the plant. The five-day week has itself been abandoned as occasion demanded— in 1929 I worked many weeks on the six-day basis.

In the fall of that year Ford declared that thenceforth $7 a day would be the minimum wage in his plants. Immediately the bosses at the plant came around yelling at us: “Go like hell. If you’re gonna get that raise you gotta increase production.” On my job production was raised from fifteen pans of stock to twenty-two—with the result that one entire shift of our gang was laid off. Down the line from me one man was given two drill presses to tend, instead of one. The inspector on our job was taken off and we had to do our own inspecting and still keep up the production rate. This terrific speed-up took place all over the plant—and immediately nearly 30,000 men were laid off.

That speed-up has been increasing ever since. In the old days Detroit workers would go to Ford’s only when they could get a job nowhere else, conditions were so bad. But now General Motors and Chrysler plants are just as bad. However, Ford can still show them a thing or two in sweating labor. As a result of the conveyor system, upon which the whole plant is operated, the men have no time to talk to each other; have no rest except for fifteen or twenty minutes at lunch time; and can go to the toilet only when substitutes are ready to relieve them. One operation upon which I worked required that I be on the job, ready to work, just as soon as the preceding shift went off; work up to the exact minute for lunch time; take a couple of minutes to clean up and get my lunch kit, and be back thirteen minutes later ready to work. There was never a moment of leisure or opportunity to turn my head.

A grinder told me recently: “The machines I’m running take up the distance of a short city block. By the time I’m at the last one the first machine has already stopped. The boss is shouting at me and I have to run back there, then back down the line again to see that the last machine doesn’t stand idle for a second. Now the boss tells me they’re going to give me more machines.” A worker on pinion gears started his job some years ago running four machines. It was later raised to six. A year ago he was given nine to look after, and in the fall he was raised to twelve—with no change in the machinery.

A worker on tire carriers, who has collected statistics on his job—where both intensive speed-up and machine changes were carried through—presents the following figures for daily shift production and the men required:

Thus in six years production more than doubled while the number of workers on this job went down to one-tenth of those employed before! (For many additional examples of Ford speed-up see Chapt. V of Labor and Automobiles by Robert W. Dunn, International Publishers.)

This speed-up, combined with the nervous tension, results in a high accident rate. No outsider hears of these accidents, for Ford has his own hospital at the Rouge, and the Detroit newspapers do not print news of Ford accidents. The day I was hired six men were killed in the power house. The Safety Department is overruled for the sake of speed. On a grinding operation upon which I worked, the dressing wheel would often burst and cause severe face injuries to the operator. The Safety Department ordered this discontinued and installed a new, safe device. A few weeks later this was removed and the old wheel put back—the new device had slowed up the work.

Wage Cuts a la Ford

The claim that wages are never cut in Ford plants has always been part of the Ford publicity line. But this is not true. When the plants reopened in 1928, after the eight months’ lay-off, and production began on Model A, thousands of older men who had been making $8 to $10 a day when they were laid off were hired again as new men at $5 a day. In many cases, the older men were not rehired—younger men were put in their places at lower wages. Beside this trick of rehiring a man at lower wages. Ford has a method of “transferring” men from department to department, their wages being cut as they are moved. I worked in 1929 with men making $6.40 who had been making $7.60 before the transfer.

Then came the general wage-cut. In the fall of 1931 Ford officials admitted, after much evasion, that wages in their plants had been cut to $6 a day.

This may sound like high wages to the innocent outsider. But most Ford workers now get only a day or two days’ work a week. And what Ford gets from them is more than just one or two days’ work, for a man working short time can be pushed harder for the day than if he worked all week. In 1930, when the wages of the Ford workers were figured at $7.60 a day, the average earnings were $959.20 for the year. This allows for the three-day week then in force and for the seven weeks of enforced idleness during the year. For 1932, if we allow for two days’ work a week, and grant that the Ford plants will not be closed down any more than in 1930—which is doubtful—the average Ford worker will not make more than $540. So much for Ford’s “high wages”!

Ford claims not only that there are no wage cuts in his plants, but there are none in any of the 3,500 plants which make parts for him. “To prevent wage cuts on Ford work, the Ford Motor Co. makes periodical inspections of its supply companies/^ says the Wall Street Journal, quoting Ford officials. Many of these supply companies are in Detroit. I shall speak only of the most prominent of them, the Briggs Manufacturing Co., which makes 43 per cent of Ford bodies. This concern gained no little fame in 1930 because its earnings during the first half of that year showed “an increase of 45.78 per cent over the $2,422,697 reported for the similar period in 1929. Earnings in the second quarter alone exceeded by $344,000 the earnings of the entire year of 1929.”

These increased earnings are explained by the 15 to 50 per cent general wage cuts which the company put through early in 1930 and the piecemeal cuts, from 5 to 30 per cent, later in the year. In 1931 it was offering unskilled jobs at twenty-five cents an hour. Besides being notorious in Detroit for its low wages, this concern also enjoys an unsavory reputation among workers because of its lack of safety devices on machinery and the resulting high accident rate. In all this, Briggs is representative of the “Ford inspected” contractors.

The highly profitable letting out of parts contracts, together with speed-up in the Ford plant, has of course led to widespread unemployment in Detroit. Department after department at the plant has been closed down—brake, rear-axle, shock absorber, differential housing—to mention only a few; while other departments run with skeleton crews. Nearly every second man I meet in the job lines has been laid off from Ford’s.

At capacity the plant employs 120,000; during 1929, 30,000 men were discharged; layoffs continued through 1930 until another 50,000 had been let out; in 1931 many thousands of production men were dismissed. With a total of about 90,000 men dismissed, you can figure out for yourself how much truth there was in the Ford claim that 80,000 were working in April, 1932.

Ford Likes Boys—to Work Cheap

One of Ford’s most touted acts of “humanitarianism” is the Henry Ford Trade School. It is proclaimed as a benevolent effort on the part of Ford to help fatherless and “delinquent” boys. Just how “benevolent” he is can be gathered from the fact that in 1931, while thousands of production men were being laid off twelve- or sixteen-year-old trade school boys, who get a week, were put on their jobs, and those who refused were either suspended or dismissed. Many workers on tool grinding, machine repair and milling machines were definitely displaced by trade school boys. One of the boys who refused to work in the foundry was suspended; another who wouldn’t take over a dangerous job in a big tank was dismissed. In such a manner does Henry Ford demonstrate his interest in fatherless boys.

So too with Negroes. Ford propagandists, both white and Negro, have claimed: “There is no racial discrimination in Ford plants.” But any Ford worker can tell you that there are few Negroes on the assembly lines and practically none in the tool room or in other skilled work. In the motor building, few of them are to be found doing work other than sweeping. But there are Negroes in the rolling mill, the foundry, the steel mills—where work is hard and body-killing.

Ford has been getting plenty of publicity for “aiding debt-ridden workers” of Inkster, a small village just outside Detroit, made up of 500 Negro families and 50 white families, the heads of which work, or worked last, in the Ford plant. Because of unemployment, high rents, installment payments, the workers are destitute. With his usual hullabaloo Ford proceeded to “rehabilitate” the village—by putting the Negro workers to work at a dollar a day and pressing their wives into service in the Ford soup kitchen, where the workers and their families have to get their meals. The company says that a dollar a day is “what is actually needed to feed their families.” For other supplies, such as clothing and shoes, the workers have to apply to the company store and sign a note saying they owe so much money to the company, which the latter can collect at any time. In short, the Ford Motor Co. is building up a system in Inkster, through holding the workers in debt to it, which is much like the peonage system under which Negroes are kept in bondage in the South.

Service Department Gangsters

The Ford “Service Department” is headed by an ex-prizefighter, Harry Bennett. He is probably the most hated and despised man in all Michigan; for his power and activities stretch much further than the Ford plants. His connection with Detroit’s gangsterdom, whom he finds useful for Ford purposes, is well known. When he was in the hospital recently, his first visitor after Henry and Edsel Ford, the newspapers reported, was Joe Tocco, downriver beer-baron. One of the ways Bennett pays his chief gangsters is to turn over to them the valuable food concessions at the Ford plant. This was the way the notorious gangster Chester La Mare was paid, after Bennett had gotten him paroled from a bootlegging conviction. When La Mare was bumped off, his food concession was turned over to a rival gangster. Twice in recent years Bennett himself has been unsuccessfully put on the spot by rival gangsters.

The Service Department which this man heads is made up, as a former member told me, of “ex-pugs and thugs.” The open section, whose members are known as service-men, acts as a police body in the plant. It checks up on men walking around; sees that workers do not talk to each other; prevents bosses from becoming too friendly with workers; and enforces the thousand and one petty regulations of the plant. The thugs are a law unto themselves. From their decision there is no appeal. At times you’re fired if you walk down the main aisle in your building. At other times you’re fired if you’re caught dodging among the machines on your way to your work place. At one time it was all right to wear a badge anywhere, just so that it was in sight. Overnight an order was issued that they should be worn on the left breast, and all who forgot to do so were laid off. In times like these, when every excuse is seized upon to lay off men, it becomes a nerve-racking ordeal to stick to the job, under the eyes of these Ford servicemen If you stay too long-in the toilet, you’re fired; if you eat your lunch on a conveyor, you’re fired; if you eat it on the floor, you’re fired; if you wait to return stock to the tool crib, you’re fired; if you talk to men coming on the next shift, you’re fired.

The secret section of the Service Department has spies scattered through the plant, working with the regular workers. They “listen in” on conversations, find out what’s going on, and locate those who voice “dangerous thoughts.” In this way even the mildest criticism of Ford meets with swift dismissal. In fact, so easy is it to get a man fired for “political agitation” that foremen have used the pretext to get rid of men they didn’t like. There are members of A. F. of L. unions in the plant, but they are tolerated because they keep their mouths shut. After the Ford Massacre, all those suspected of Communist sympathies were fired and spies were sent in among the workers to locate those who expressed sympathy with the marchers. At the time of writing, all Ford workers are required to open their lunch boxes for inspection when they enter the plant. Ford fears the distribution of leaflets.

His Workers Begin to Revolt

Well may he fear the distribution of leaflets, for the Ford workers, desperately driven, need only trusted leadership and the conviction that their fellow-workers will act with them. Ford’s inhuman policy has turned even the most backward workers into bitter, brooding men who are beginning to organize and fight.

Ford’s trick of flooding Detroit with labor has already caused outbreaks. Early in 1929, he announced he would hire 30,000 men. Thousands of workers, many of them with their families, and penniless, rushed to Detroit. Night after night, in bitter zero weather, they stood in line. A few hundred were taken on. Fire hoses were turned on the rest to drive them away. A similar situation arose in 1930; with the result that 10,000 unemployed stormed the plant and smashed the hiring office and the woven-steel fence which protected it. After that the police inaugurated a policy of repression. Men were not allowed to start fires to warm themselves; they were prohibited from gathering in groups; they were required to keep moving; if they were in line they had to move quickly if they were to avoid being beaten. On at least one occasion an unemployed worker was killed by the police when he resisted their attempt to put him at the end of the line, after he’d been standing in line all night.

An even more important revolt occurred inside the Ford plant in the summer of 1931. Thousands of workers, already desperate with fear of unemployment, were laid off at one stroke. They rebelled, smashed machinery, and fought off the service-men. Machine guns were set up in the affected departments and the workers threatened with death if they did not surrender. While these men were being paid off, the pay office resembled an arsenal.

Bloody Monday

During the fall and winter of 1931-32, the ranks of the unemployed were swelled, while relief rations were steadily cut. When, therefore, the Auto Workers’ Union and the Detroit Unemployed Councils called for a Hunger March on the Ford Plant, there was no lack of volunteers. On the coldest day of the year, Monday, March 7, some 5,000 men, women and boys set out to see Henry Ford, to demand jobs and relief, and abolition of the Service Department.

We know Ford’s answer too well! After pushing back Dearborn police for nearly two miles, in spite of repeated tear gas attacks, the marchers were met at the plant with pistol and machine gun fire, while Edsel Ford, Mayor Clyde Ford of Dearborn (a cousin of Henry), and ex-governor Fred Green, calmly looked on.

Four of the marchers were killed: Joe York, 19, Joe Bussell, 16, both leaders of the Young Communist League; Coleman Leny, 25, and Joe de Blasio, 27. Twenty-two more collapsed under the withering fire. How many more, with club and gun wounds, went to private physicians for treatment is not known —but eyewitnesses agree they must run close to a hundred.

Right after the massacre a regular reign of terror began. The wounded were put under arrest and chained to the hospital cots; the offices of the Trade Union Unity League, the Auto Workers’ Union, the Unemployed Councils, and the Communist Party, were raided. Communist leaders, including William Z. Foster, Communist candidate for president, were threatened with life sentences.

But within twenty-four hours of the massacre, it was plain even to the dullest capitalists in Detroit, that they dared not further antagonize the working class. The newspapers, which on the first day had talked of a “red riot” and “howling mob,” backed down and admitted that the marchers had been bent on a peaceful and legal mission. Even the Prosecutor, Toy, a Ford dummy, changed his mind about indicting the march leaders for criminal syndicalism, and swore he would “investigate both sides.”

Just how “impartial” this investigation was can be seen in the fact that no police were arrested—although all the slain and wounded had police bullets in their bodies. The sessions of the Grand Jury were declared secret and their first witness was that notorious labor spy and ex-operative of the Department of Justice—Jacob Spolansky. Assistant Prosecutor Culehan who conducted the “investigation” told newspapermen: “I don’t care who knows it, but I say I wish they’d killed a few more of those damned rioters.”

When the workers who appeared to testify pointed out that the questions put to them were quite irrelevant to the case, Culehan threatened to put them in prison for contempt of court. He declared that if any one of them told any one outside the court room about the proceedings he would be immediately jailed! This is not surprising in view of the questions he compelled these unemployed men and women to answer: Do you go to church? Do you prefer the Red Flag to the Stars and Stripes? What would you do if you inherited $7,000,000? Do you know that Foster might have as much money as Henry Ford? Don’t you know that you could save millions of dollars if you worked at the Ford plants?

Whitewash of the police murderers was a foregone conclusion.

The Workers Answer

How strongly the auto workers of Detroit felt about the Ford massacre was manifested at the mass meeting on Friday, March ii, and the mass funeral the next afternoon. The largest hall in Detroit could not hold those who came to protest. There were 6,500 seats, but the seats didn’t count, they were pushed together, the aisles were filled, the hall packed to the doors, and thousands stood outside unable to get in. There were easily 15,000 in and about the protest meeting. After the meeting, and far into the night, the thousands of Negro and white workers stood in lines extending for blocks, waiting to look upon the four dead comrades lying in state at Ferry Hall. And early the next morning the lines had formed; and hours before the time of the funeral, the streets were packed with men, women and children waiting to march.

At the sight of the vast line of marchers filling the chief thoroughfare of Detroit, said one observer, he had to remind himself that this was not “Red Berlin,” but American Detroit. But “American Detroit,” meaning a 97 per cent non-union town—the boast of the Detroit Employers’ Association—^will soon be a thing of the past. Those 40,000 men and women who swore in the cemetery to avenge the four murdered workers and their shattered comrades, are but the vanguard of the on¬ coming organized auto workers.

Over the common grave in which the four bodies lie, facing the Ford plant, there will stand a monument erected by the workers, to commemorate their dead brothers, to be a symbol of the new day which is dawning for the workers of Detroit.

Workers of Detroit have learned profound lessons from the Ford Massacre. They have learned that even such immediate demands as jobs and relief are met by bullets. They have learned that the only way to prevent more massacres is to build their working class organizations so broadly and firmly that the capitalists dare not attack them. This is why many of them are joining the militant Auto Workers’ Union and the Unemployed Councils.

Equally important, they have learned the true role of the liberals and the Socialists as shown by the fact that many Detroit workers are joining the Communist Party.

Mayor Murphy of Detroit was elected, with the aid of the Socialist Party, on promises of unemployment relief, abolition of police terrorism and institution of free speech. During his term of office over 25,000 families of unemployed have been struck off the welfare lists, which means that they get no help from the city whatsoever, and those who remain on the list have had their relief cut steadily until today it is admittedly far below the minimum subsistence level set up by social workers.

Police terror continues, especially against the Negroes. Several Negroes have been shot and beaten by police but no rebuke from the mayor has been forthcoming. And so with free speech—the police attacked an anti-war demonstration in Grand Circus Park in November, 1931, and demonstrations before city welfare stations have been broken up with the usual brutality.

It was the Ford Massacre, however, which disillusioned many workers about Frank Murphy. Although he tried to cover up the fact, his police were right there during the shooting, as Inspector Black admitted to the Detroit Free Press on March 8.

And after the massacre, his police raided the offices of working class organizations, picked up survivors and turned them over to Ford’s Dearborn police. When questioned, he admitted that his police had been sent to the massacre, “but they got there after it was over,” he said. “Of course, it is my duty to send my police when there is disorder and they are asked for.” In other words, every time some capitalist has his thugs fire on workers, Murphy will send his police to join in the shooting. The massacre brought out the function of Mayor Murphy and the Socialists who supported him—to keep the workers unorganized and trusting in them, and when the workers try to help themselves, to shoot them down.

“Smash the Ford-Murphy Police Terror” was the slogan of the mass funeral. The funeral itself smashed the terror, for Murphy’s police had first forbidden it, then backed down when they saw the response of the workers.

In 1905 the unemployed of Petrograd received the same answer as our comrades when they asked for bread—bullets. And when they had buried their dead they had learned a lesson—to expect nothing from the capitalist class, and to prepare for working class emancipation by working class organization. They did organize and they did prepare for the hour of freedom. Twelve years later they delivered their answer—with a blow which shook capitalist society to its depths they smashed the whole rotten structure of capitalism and set to build a socialist society. Their success has been such that the eyes of the workers of the world are upon them.

So also must the workers of America answer the Ford Massacre.

The End of the Ford Myth by Robert L Cruden. International Pamphlets No. 24. International Publishers, New York. 1932.

International Publishers was and is a printing house of the Communist Party USA

PDF of full pamphlet: The End of the Ford Myth by Robert L Cruden. International Pamphlets No. 24. International Publishers, New York. 1932.