James S. Allen was the editor of Southern Worker and among the Communist Party’s leading theoreticians of race and slavery in the United States during the 20s and 30s.

‘Sharecropping as a Remnant of Chattel Slavery’ by James S. Allen from The Communist. Vol. 13 No. 12. December, 1934.

SHARECROPPING is that specific economic slave survival which lies at the basis of the oppression of the Negro people, and is the most important single factor which marks the non-completion of the bourgeois-democratic revolution. Before establishing the extent of this economic slave hangover today and its relation to capitalist development in the South, it is first necessary more firmly to establish its nature.

American bourgeois economists are practically unanimous in defining sharecropping as wage labor, even of a higher form than labor paid in cash wages and differing from the latter only in that it is paid in kind. The stages in development from a lower to a higher plane of farm labor are envisaged by them somewhat as follows: first comes wage labor, then sharecropping, which is the first rung in the tenant ladder. Then, via the other forms of tenancy, the worker may graduate into the class of landowners. One writer, for instance, declares:

“The share tenant is in reality a day laborer. Instead of receiving weekly or monthly wages he is paid a share of the crop raised on the tract of land for which he is responsible.” (Robert P. Brooks, The Agrarian Revolution in Georgia, 1865-1912, pp. 65-66.)

The legal codes of some of the cotton States classify the cropper as a “wage laborer working for the share of the crop as wages”. The Georgia Supreme Court in 1872 decided that, “The case of the cropper is rather a mode of paying wages than a tenancy” and has remained by this decision since. A later decision revealed the motivation behind this classification:

“Where an owner of land furnishes it with supplies and other like necessaries, keeping general supervision over the farm, and agrees to pay a certain portion of the crop to the laborer for his work, the laborer is a cropper and judgments or liens cannot sell his part of the crop until the landlord is fully paid…” (Ibid., pp. 67-68.)

The sum total of this decision was that, as a wage-laborer being paid in kind, the cropper has no title to the crop, upon which the landlord has first call. On the other hand, the same objective is obtained in those States where the cropper is legally considered a tenant. Here, “where the landlord desires to avoid statutory requirements, he may obtain full title by written agreement. In such cases the cropper loses his legal status as a tenant.” (C. O. Brannen, Relation of Land Tenure to Plantation Organization, U. S. Department of Agriculture, Bulletin No. 1269, p. 31.)

C. O. Brannen, agricultural economist of the U. S. Department of Agriculture, holds that the cropper occupies an intermediary position between the wage-worker and the farm tenant, between which positions he may be shifted, depending upon the state of the labor market, the planters sometimes being “obliged to raise their wage hands to the cropper status”! According to this writer, “the consistent increase of tenancy in the South since the Civil War indicates an improvement in the status of farm labor”. (ibid., pp. 2223; 32-33.)

Neither historically nor from the point of view of their economic content is this comparison between the various forms of labor and tenancy correct. Historically speaking, it is true that wage-labor, in a greatly modified form, was probably prevalent on the Southern plantations in the first two years immediately following the Civil War. But this was an expression of the revolutionary situation which existed in the South at that time, and came much closer to a solution of the bourgeois-democratic tasks than did the system of sharecropping. Wage-labor, even as practiced during those years, was a much “freer” form of labor than the first forms of sharecropping. Sharecropping and related forms fulfilled the function of assuring labor the year through, and even longer, to the planter, of binding it to the plantation. And sharecropping continues to serve this function to the present day. Both Brooks and Brannen are forced to admit this, despite their smooth and utopian picture of the ladder of progress. “The wage hand was an uncertain factor in that he was liable to disappear on any payday,” declares Brooks, in discussing the rea sons for the prevalence of sharecropping. ““The cropper is obliged to stay at least during an entire year, or forfeit his profits.” (Brooks, op. cit., p. 66.) In fact, within the limits of the sharecropping arrangement, the planter often, when plowing, planting, cultivating or picking demand it, quite forgets the individual business deal he is supposed to have entered upon with his croppers: he will work them in gangs, plowing or carrying out other operations over the whole plantation at one time, regardless of the “individual holdings”.

In remarking upon an increase of tenancy, especially cropping, during the World War and after, when large numbers of Negroes migrated out of the Black Belt, Brannen says:

“…Considerable numbers of planters, both of cotton and sugar cane, have shifted in part during the World War from the wage to the tenant system. Under present conditions (in 1920) some of these will probably return to the wage system, provided the labor supply becomes normal…When a scarcity of labor has occurred planters have been obliged to raise [!] their wage hands to the cropper status or lose the labor and allow croppers to become renters” (Our italics. Brannen, of. cit., p. 22.)

A constant supply of labor is a prerequisite for capitalist relations of production and under capitalism it is a “normal” condition that there should always be at hand a large reserve labor army, or that such an army should be constantly in the process of becoming by the expropriation of the tillers of the soil or, as in the United States, that a constant labor supply migrate from regions where such expropriations are taking place. Only when there was a relative abundance of labor power at hand, which was not being depleted by industrial development, could wage labor be safely employed on the Southern plantations. But as soon as this supply was beginning to vanish, as happened during the World War, the immediate effect was greater utilization of sharecropping, i.e., of binding the laborer to the soil more firmly. As Brannen himself so aptly puts it: “From the landlord’s point of view, the use of cropper rather than wage labor may be a means of stabilizing the labor supply.” (ibid., p. 32.) Speaking of the relative merits of the employment of day laborers, the same author states that while the planter has the advantage of not having to support them when their labor is not needed, “it [wage labor] has the disadvantage of compelling the plantation operator to engage in costly competition for labor when labor is scarce”. (ibid., p. 26.) Who does not know that under competitive conditions and with a restricted labor market, the worker will get higher returns for his labor power? Both from the point of view of better conditions for the worker and from the point of view of its social nature, wage labor is a higher form of labor than sharecropping and reflects in those regions where it is predominant the existence of a higher and more progressive stage of social development.1

In reality, sharecropping is neither a higher form of labor than free wage labor, nor does it hold a position between the latter and higher forms of tenancy. The significance of sharecropping lies in the fact that it represents an intermediary stage between chattel slavery, on the one hand, and either wage labor or capitalist tenancy on the other. Two courses of development were possible after the Civil War within the limits of the fulfillment of the bourgeois- democratic revolution: either the break-up of the estates and the establishment of petty-proprietorship which might then develop into large-scale capitalist farming, a necessary accompaniment of which would be the creation of a large army of wage workers, or, even failing the confiscation of the estates, the immediate utilization of the former slaves as wage-workers on large capitalist farms. But with the failure to carry through the bourgeois-democratic revolution, neither of these possible solutions took place, either one of which would preclude the carrying over of slave forms of labor as the dominant forms. Instead landowners, and, to some degree, capitalist tenants, continued to operate the large estates, which for the most part remained intact, utilizing semi-slave forms of labor.

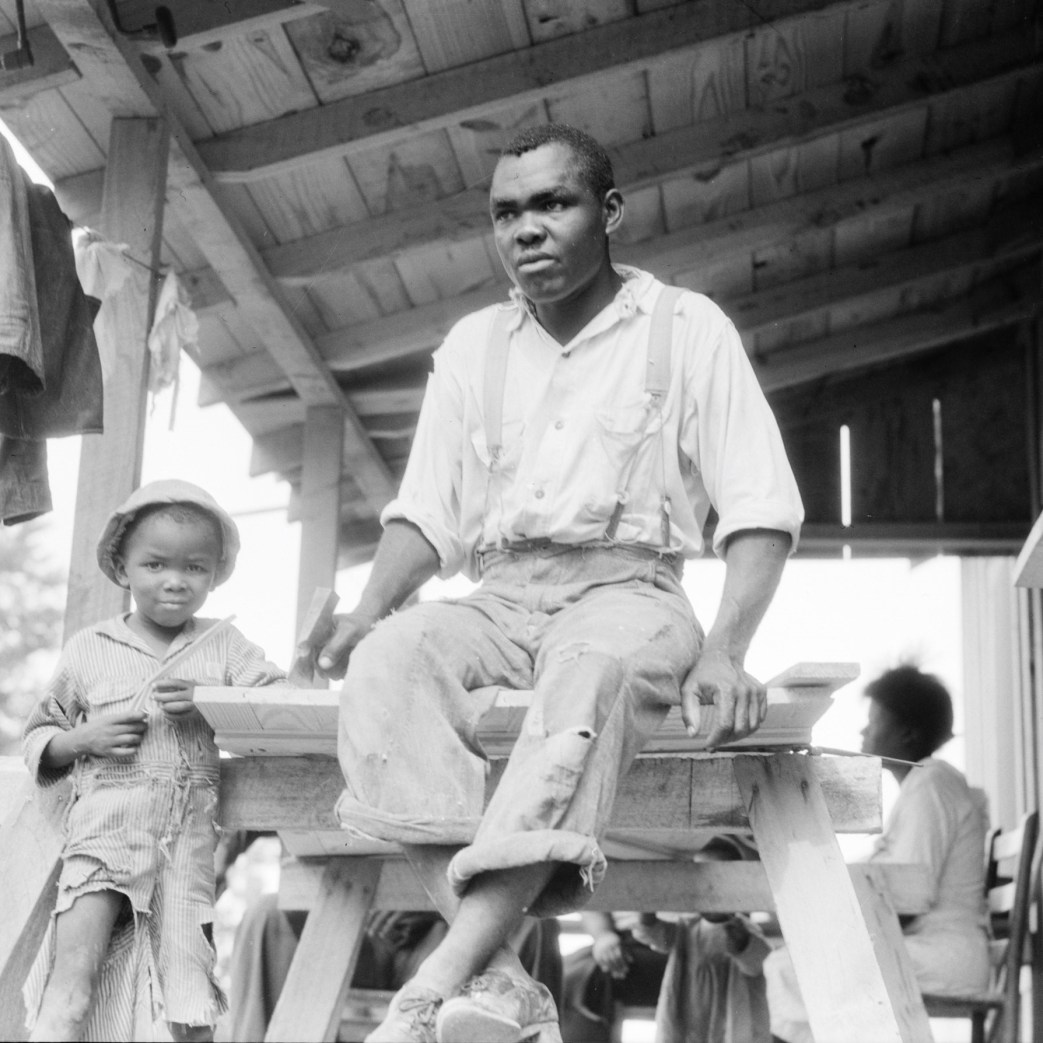

What is the specific slave content of sharecropping and the forms of tenancy which exist in Southern agriculture? An analysis of the forms of labor and relations of production which prevail in the cotton plantation areas should reveal the very source from which arises the whole superstructure of the oppression of the Negro people. Here is that specific economic factor which reveals the half-way abolition of chattel slavery and from which flows the whole complex of violent and all-pervading persecution, discrimination, jim-crow, “race hatred”, white superiority, etc., which surrounds the American Negro.

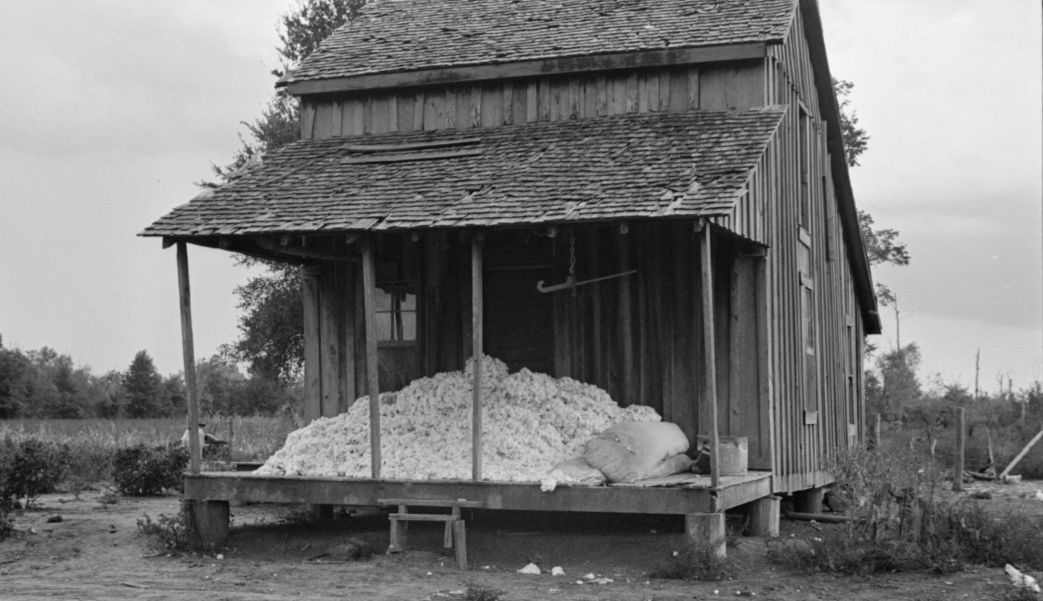

Among non-landowning tillers of the soil in the South, there are three principal categories, excluding wage-labor. These are the sharecroppers, the share-tenants and the renters. In the case of the sharecropper, all the means of production—the land, implements and working stock—are owned by the landowner. The cropper is assigned a portion of land and a cabin. For the use of the means of production the cropper is theoretically supposed to give the landowner half of the crop. Out of the other half of the crop (which is supposed to constitute either his wages in kind, or that portion of the crop left after he has paid his rent in kind) the landowner deducts for all food and other necessities advanced during the season s well as for certain costs of cultivation, such as fertilizer. At all times the cropper works under the close supervision of the operator or his agents. He has no control over the nature of the crop, the acreage, methods of cultivation, nor over the marketing of the crop. He has none of that independence, as limited as it is by the dominance of all forms of monopoly, which is enjoyed by the very smallest of farmers or tenants in non-Southern areas. In reality, the settlement at the end of the year amounts to the cropper having received barely enough subsistence from the planter in the form of advances to remain working, with a little cash thrown in very occasionally perhaps at Christmas time during an especially good year. More often, the cropper finds himself still in debt to the planter after the cotton picking and the marketing of the crop and he is forced to remain, under the provisions of the crop lien, until the debt is worked off or another planter agrees to buy the debt and with it the peon. Legalization of this state of affairs is to be found in the vagrancy statutes, emigrant agency laws and laws penalizing tenant farmers, croppers or wage-workers for failure to complete cultivation of the crop after once having entered into a contract with a planter. (See Walter Wilson, Forced Labor in the United States, Chaps. VI and VII.) The social oppression and degradation of the masses corresponding to such forms of economic bondage can well be imagined.

The share-tenant is distinguished from the sharecropper principally in the fact that he owns part of the means of production and makes an investment in the undertaking. He furnishes his own work stock and feeds it, and also supplies his own implements and seed. Rent is paid in kind, either one-fourth or one-third of the crop, and fertilizer expenses are shared in proportion to the ratio of each party’s share of the crop. The share-tenant must also submit to supervision by the landowner or his agent. Since he must take advances from the landowner, or the supply merchant directly, the share-tenant is also caught in the credit net and is accordingly subject to a high degree of supervision, including the marketing of the crop.

There is a real distinction here in the status of the tiller of the soil, although his actual condition of semi-servitude is but little removed from that of the sharecropper. The share-tenant has a greater degree of independence in that he is to some extent his own capitalist, owns part of the means of production and makes part of the investment in the undertaking. This form of tenancy is sometimes combined with cash renting, when the share-tenant may pay cash rent for land on which he grows corn or some other food crop.

The renter most closely approaches tenancy as it prevails in highly developed capitalist areas. The standing renter pays his rent for the land with a fixed amount of the product, he pays rent in kind, and furnishes his own equipment and costs of production. In cash renting, the highest form of tenancy, the tenant pays a definite sum per acre or per farm as rent. Where such a renter is a small farmer, his work is often also closely supervised by the planter, who is interested in the crop for the rent as well as in many cases for advances of food and other necessities.

It is clear, therefore, that only the various categories of the share-, standing and cash tenants may properly be considered as tenants, although in their relations with the landlord there are strong semi-feudal elements, such as close supervision by the landowner and rent in kind, as well as the peculiar features of the Southern credit system. Of these, the share-tenant is the most harassed by the slave survivals and is often but slightly distinguished from the sharecropper. Capitalist tenants, in the sense of employment of wage labor, are to be found almost exclusively among the classes of standing and cash renters, among whom there also occur largescale capitalist farmers, as well as small or poor farmers.

It must not be imagined that there is a strict line of demarcation setting off the tenant classes, on the one side, in the sphere where only semi-feudal relations of production exist, and, on the other, where only capitalist relations of production exist. The economic slave survivals make themselves felt in all phases of Southern economy, not only in agriculture but also in the forms of labor exploitation sometimes taken over by industry. And capitalist relations of production have also penetrated into the plantation system, so that on any single plantation one may find side by side wage-labor, sharecropping, share-tenancy and renting. In close proximity, one will find as well even a small-scale self-sufficing economy, the capitalist tenant, the small capitalist landowner, the plantation junker, and the large capitalist undertaking.

Share-tenancy is on the borderline between sharecropping and higher forms of tenancy, and is really a transition between the two. In reality, share-tenancy corresponds to the metarie system in Europe, which served as a form of transition from the original forms of rent (labor rent, where rent is paid by the direct labor of the tiller of the soil on the land of the overlord; rent in kind; and money rent as a transformation of rent in kind) to capitalist rent. Although in the South of the United States share-tenancy had as its predecessor the slave system and bears its imprint, in form it does not differ from the metarie system. In his discussion of the “Genesis of Capitalist Ground Rent” in Volume III of Capital, Marx describes the metarie system as follows:

“…the manager (tenant) furnishes not only labor (his own or that of others), but also a portion of the first capital, and the landlord furnishes, aside from the land, another portion of the first capital (for instance cattle}, and the product is divided between the tenant and the landlord according to definite shares, which differ in various countries. In this case, the tenant lacks the capital required for a thorough capitalist operation of agriculture. On the other hand, the share thus appropriated by the landlord has not the pure form of rent…On the one hand, the tenant, whether he employ his own labor or another’s, is supposed to have a claim upon a portion of the product, not in his capacity as a laborer, but as a possessor of a part of the instruments of labor, as his own capitalist. On the other hand, the landlord claims his share not exclusively in his capacity as the owner of the land, but also as a lender of capital.” (Kerr edition, p. 933.)

This describes the situation of the Southern share-tenant, who in addition to his labor also provides a portion of the first capital in the form of implements, work stock, seed, etc. The landlord has additional claim upon the product not only in that he has lent the land to the share-tenant but also other capital, in the form of food and other advances. But the above does not yet describe the situation of the sharecropper, who provides no portion of the capital and can have no claim upon a portion of the product even in a restricted capacity as capitalist. Is the sharecropper, then, a free worker, free in the capitalist sense, i.e., he himself is no longer a direct part of the means of production as a slave and the means of production do not belong to him?

Under the slave economy, says Marx, or,

“…that management of estates, under which the landlords carry on agriculture for their own account, own all the instruments of production and exploit the labor of free or unfree servants, who are paid in kind or in money, the entire surplus labor of the workers, which is here represented by the surplus product, is extracted from them directly by the owner of all the instruments of production, to which the land and, under the original form of slavery, the producers themselves belong.” (Capital, Vol. III, p. 934.)

Is the sharecropper that “unfree labor” on the “estates” in this characterization? He is; he is paid in kind and sometimes partly in cash, in the form of food and shelter, the amount of cash received in part determining the extent to which he is free. Not only in effect but also in form the entire surplus labor represented by the surplus product is extracted from the cropper directly by the landlord. ‘The slave received a bare subsistence, the entire product he produced on the land was appropriated by the landowner. In the case of the sharecropper, one-half of the crop is claimed by the landlord from the beginning by virtue of his monopoly of the land and implements, thus assuring from the start a goodly portion of the surplus product produced by the tiller of the soil. But the landlord manages to extract directly the full surplus labor, additional unpaid labor, beyond that portion assured him from the start. The bare subsistence of the cropper and his family is provided in the form of food and shelter, which are taken out of the remaining half of the crop and which generally represent the total wages received by the cropper. The cultivation of cotton as the principal commercial crop of the plantations causes these wages in kind to be paid not in the product raised, with the exception of corn, but in meagre food supplies measured in terms of cotton raised by the tiller of the soil. In the case of free wage-labor, the surplus labor is extracted from the worker under cover of a contract and is hidden in the regular money-wage paid, which makes it seem as though the laborer were being paid for the entire duration of his labor for the employer. In the case of the sharecropper the method of extracting the surplus labor is more direct, with remuneration for the labor necessary to keep the worker alive not hidden in the money-wage, but paid directly in the necessary subsistence. Although the sharecropper no longer appears as a part of the means of production, as did the slave, the method or form under which the surplus labor is extracted by the landowner differs but very little from that of chattel slavery.

The existence of sharecropping in a highly developed capitalist society makes it possible for the cropper to appear occasionally in the capacity of a wage-worker, hiring himself out for money-wages at such times when his labor is not essential on his patch of the plantation. But this occasional appearance of the cropper as a wage-worker does not alter his basic characteristic as a semi-slave. He differs from the slave in that he is no longer a part of the means of production owned by the planter, and may occasionally appear as a free wage-laborer, but, like the slave, his entire surplus labor, as represented by the product of his toil, is appropriated directly by the land-owner.

In his theoretical title to half the crop (a title which is not legally recognized in a number of Southern States), in the entirely abstract promise of half the product of the cropper’s labor, sharecropping contains elements of transition to capitalist tenancy. But this subdued promise, as well as the transition to free wage-labor, is restricted by the fact that the sharecropper is not entirely “free” from the means of production, in this case, the land. He does not have permanent tenure of the soil, nor is he bound to the soil either by forced possession of it, as was the case of the serf (for land was not a commodity which could freely be bought and sold), or by chattel bonds to the land-owner, as was the case with the slave. He is bound to the soil by direct coercive measures—by contract enforced by the State for the period of the growing year, and beyond that by peonage, by debt slavery which is made all the more coercive by the credit system under the domination of finance capital. The fact that he is not owned by the landlord or capitalist tenant, allows him that degree of freedom which permits changing masters under certain circumstances. The existence of sharecropping in a capitalist environment also admits a greater degree of freedom in the presence of capitalist relations of production in there being at hand an avenue of escape from the semifeudal relations between master and servant. It is precisely in this element of bondage to the soil, of direct coercive measures to enforce it, that the share-tenant and to a lesser degree other tenants in the South, despite their restricted capacity as capitalists, share with the cropper in suffering from the survivals of the slave system.

The price which the land-owner paid for a slave was “the anticipated and capitalized surplus value or profit…to be ground out of him”.2 For the land-owner the money paid for the slave represented a deduction from the capital available for actual production, and this deduction from capital had ceased to exist for the land-owner until he sold his slave once more. An additional investment of other capital in production by means of the slave was necessary before he began to exploit him. Under sharecropping, the land-owner is saved his initial deduction from capital in the purchase of the slave; he invests only in his advances to the cropper and in the costs of production. It costs about $15 a year under chattel slavery to feed and maintain a slave. In the sharecropping system in normal years the average advance for each cropper family was about $15-20 a month during the seven months of the growing season (Brannen, op cit., p. 62). In 1933, the average annual furnishings supplied by landlords to croppers amounted to from $50 to $60. (A. T. Cutler and Web Powell, “Tightening the Cotton Belt,” Harper’s, February, 1934.) Now, this advance is supplied to a cropper family, which usually has more than five and more often close to ten members, some of whom may earn a little on the side as wage-workers on the landlord farm or in a nearby town. But the actual running invest-ment in supplying the subsistence of life to the worker is hardly any higher, and sometimes even lower, than under slavery, and if one considers the initial deduction in capital in the purchase of the slave, even much less. In addition, the land-owner is relieved of the necessity of maintaining his labor over dull periods as, for instance, during the months intervening between the chopping and picking of cotton and between the harvest and the planting of the next crop, or during periods of crises. Under terms of the contract, verbal or written, protected by the State power, the landlord may force the croppers to remain on the plantation without at the same time advancing food and other supplies, a state of affairs which becomes common throughout the cotton belt during periods of crises or of low prices for cotton. Under the Roosevelt acreage reduction program, which in 1934 provided for a reduction in cotton acreage of about 40 per cent, large numbers of croppers and other tenants are simply being released from their bondage to the soil, with no hopes of employment elsewhere.

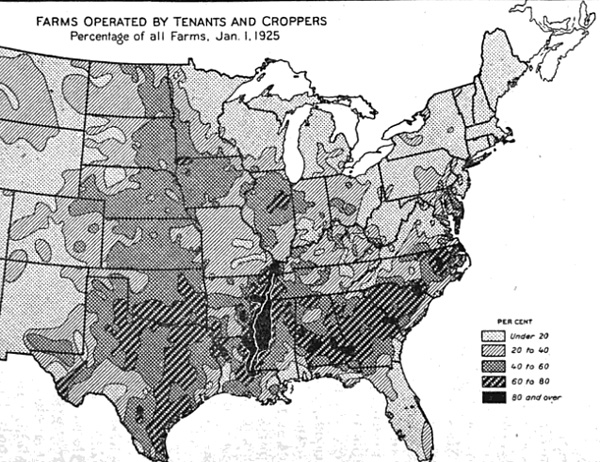

Sharecropping and share-tenancy can only be dominant in a specific social content. Their prevalence is inconceivable where a highly developed form of capitalist agriculture prevails. Of the various forms of tenancy in the South, only cash renting can be likened to the dominant form of tenancy of the North.

Tenancy in the North is the culmination of an altogether different process than in the South. Northern agriculture is undiluted by feudal remnants. Here tenancy is, in general, the result of the impoverishment of the small and middle independent landowners by finance capital through mortgages and other forms of usury, monopoly prices in manufactured products, State taxes, control of marketing of farm produce, exorbitant freight charges, etc. Here tenancy has developed on the basis of the capitalist relations of production; in the South it has grown out of the slave system. To a large extent the impoverished and expropriated farmers of the North vanished into the stream of population that was flowing from country to city. In the decade 1890-1900 the net migration from rural to urban communities was estimated at 2,500,000; in 1910-1920 it had reached 5,000,000. Many of these included the children of farming families and farm workers who were displaced by increased agricultural production per worker made possible by the extensive use of farm machinery and improved methods of cultivation. But this flow of population also concealed the cry of expropriated farmers. The wide expanse of the public domain which did not become fully settled until the end of the 19th century and the flow of immigration from abroad had made possible the existence of extensive independent landownership precisely during the period of the most extensive development of large-scale industry. American industry was absorbing the expropriated peasantry of Europe with the result that the extensive expropriation of the farmers in the United States became unnecessary for the creation of a large labor reserve for industry. In addition, large-scale capitalist production in agriculture could develop upon the basis of the seizure of large parcels of the public domain by the capitalists, and the early and intensive use of farm machinery. But as the public domain became exhausted, as monopoly capitalism developed, expropriation began in earnest as reflected in the large migration of the farm population to the cities in 1890-1900. The cutting off of the labor supply from abroad by the World War at a time when increasing demands were being made of industry hastened this expropriation as can be seen in the huge figure for the city-ward migration in 1910-1920, although a large portion of this migration came from the South.

To a certain extent the expropriation of the farmers was also reflected in the rapid increase of tenancy in the North. We say to a certain extent because an increase of tenancy does not necessarily mean a corresponding expropriation of the farm population. Many of the tenants in the North are in fact middle or well-to-do farmers, and some of them even large-scale capitalists. It is possible for a land-owning farmer to become a tenant without shifting from his class as a small, middle or well-to-do farmer. ‘The rapid increase in tenancy in the North since 1900 is, however, indicative of impoverishment, since foreclosures and other forms of expropriation not only deprived the farmer of his land and buildings, but also of his other capital, so that it was only as a much poorer capitalist that he could rent land, if at all, and continue as a farmer to be subject again to the same inexorable thirst of finance capital. Complete expropriation, not only of land and building, but also of machinery, livestock and other capital, as is more common during the present crisis, is reflected not primarily in the growth of tenancy, but in the decrease of the number of farmers, who have been so completely expropriated that they cannot even become small tenant farmers.

In the South, however, tenancy is not as a rule the result of the partial expropriation or impoverishment of the land-owning farmer, but has as its general basis the existence of the large landed estates perpetuated after the abolition of chattel slavery, the monopoly of the land by the owners of estates and plantations. It is the result of the non-completion of the bourgeois-democratic revolution and not, as in the North, the result of impoverishment of the farming population brought about by finance capital on the basis of capitalist relations of production in agriculture. Of course, this form of expropriation also takes place in the South, but it is not the chief basis for the existence of tenancy.

This leads to another difference of basic importance between the forms of tenancy in the North and in the South. Marx points out in his third volume of Capital that the progressive features of the capitalist mode of production in agriculture consist, on the one hand, in the rationalization of agriculture, which makes it capable of operating on a social scale and, on the other hand, in the development of capitalist tenants. While the latter has an adverse effect upon the former in the sense that tenants on the land hesitate to invest capital on improvements and often permit the land to deteriorate, the development of capitalist tenancy performs a two-fold progressive function. With regard to pre-capitalist forms of agriculture, it separates land-ownership from the relations between master and servant; the land-owner himself or his manager is no longer the direct overlord of the tillers of the soil, as was the case on the feudal domain or under slavery. With regard to post-capitalist development, capitalist tenancy “separates land as an instrument of production from property in land and land-owners, for whom it represents merely a certain tribute of money, which he collects by force of his monopoly from the industrial capitalist, the capitalist farmer”. Land thus more and more assumes the character of an instrument of production and as such is separated from private property in land which merely signifies a monopoly over a parcel of land which enables its owner to appropriate a portion of the surplus value produced by the workers on this land in the form of rent. This is “reductio ad absurdum of private property in land”, declares Marx, and he points out that the capitalist mode of production “like all its other historical advances” brought about this as well as rationalizing of agriculture “by first completely pauperizing the direct producers”. (Capital, Vol. III, pp. 723-724.) Capitalist tenancy, therefore, in making the land-owner merely a rent collector, an appropriator of surplus labor, and in stripping the actual farmer of land-ownership, paves the way for the abolition of all private property in land and, once the land-owner is stripped even of his capacity as rent collector, for the Socialist operation of agriculture.

This progressive feature of capitalist tenancy is present only in a restricted sense in the South. Tenancy in the South, because of the foundation upon which it developed and exists today, does not exhibit the progressive features of capitalist tenancy. As regards the past, tenancy did not succeed in separating on a general scale land-ownership from the relations between master and servant; in fact, it prolonged and strengthened these relations, it perpetuated in a highly developed capitalist country powerful remnants of chattel slavery. Nor, as far as the dominant forms of tenancy are concerned, was its corollary developed, the separation of land as an instrument of production from private property in land. The Southern landlord who rents his land out to share-tenants or even renters, maintains direct supervision over production, despite the intervention of rent in kind which, in this case, does not serve to draw a sharp line of distinction between the relations of production and landownership. To the small degree that absentee landlords have rented out their land to large plantation operators, or in small lots to independent cash renters, can capitalist tenancy be considered as existent in the South.

Without possessing any of the progressive features of capitalist tenancy, the tenant system in the South partakes of its chief evils. Tenancy is one of the greatest obstacles to the rational development of agriculture because the tenant will not invest in improvements on the land, which would only add to the capital of the land-owner. A special study revealed that out of some 55,000 rented farms in the United States for which data was collected, 36 per cent reported decreasing fertility of the soil. But in 50 counties of the South, 56 per cent of the rented farms were reported as decreasing in fertility. The greater the number of tenants under a single landlord, the greater the loss in soil fertility; 63 per cent of the landlords in the 50 Southern counties who have five or more tenants, a unit which in most cases may be classed as a plantation, reported decreasing soil fertility. (Turner, The Ownership of Tenant Farms in the United States, p. 41.) The retarding influence of tenancy on the technical development of agriculture is further accentuated in the South by the cultivation, year in and year out, of cotton as the commercial crop, which has the effect of deteriorating the soil and demands advanced methods of preservation if the land is not ultimately to become useless. Many of the tenants, especially on the non-plantation and small plantation farms, own only the most wretched stock and implements and are in no position to give the soil the attention it needs. The credit system, with its insistence upon cotton as the principal crop, does not permit the farm operator, if he desires credit, to rotate crops and is thus a powerful factor in bringing about the utter desolation of the soil in large stretches of the older cotton belt.

NOTES

1. As between sharecropping and the various forms of tenancy in the South, the former offers the most profitable field of exploitation for the planter. In “A Study of the Tenant Systems in the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta”, made by the Department of Agriculture in 1913, it was found that the average yearly income of sharecroppers was $333, of share tenants $398, and of cash renters $478. The profit obtained by the landlord was in inverse proportion: his income from sharecroppers yielded on an average of 13.6 per cent on his investment, in the case of share tenants his return was 11.8 per cent, and in the case of cash renters between 6 per cent and 7 per cent. “It is…easy to understand why, in practically all cases where landlords can give personal supervision to their planting operations, they desire to continue the sharecropping system as long as possible,” sagely remarks Woofter in his Negro Migrations, p. 75.

2. Marx, Capital, Vol. III, p. 940.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v13n12-dec-1934-communist.pdf