One of the largest and most effective mutual aid campaigns of the early Depression was Seattle’s Unemployed Citizens League. What began in July, 1931 by October had 22 branches in the city. A year later it would count tens of thousands of members in the Seattle area. Carl Brannin reports on how the movement expanded to other cities.

‘Northwest Unemployed Organize’ by Carl Brannin from Labor Age. Vol. 21 No. 6. June, 1932.

“IF the bankers and captains of industry who admit their helplessness in solving unemployment, would stand aside we’d show them how to deal with the problem.”

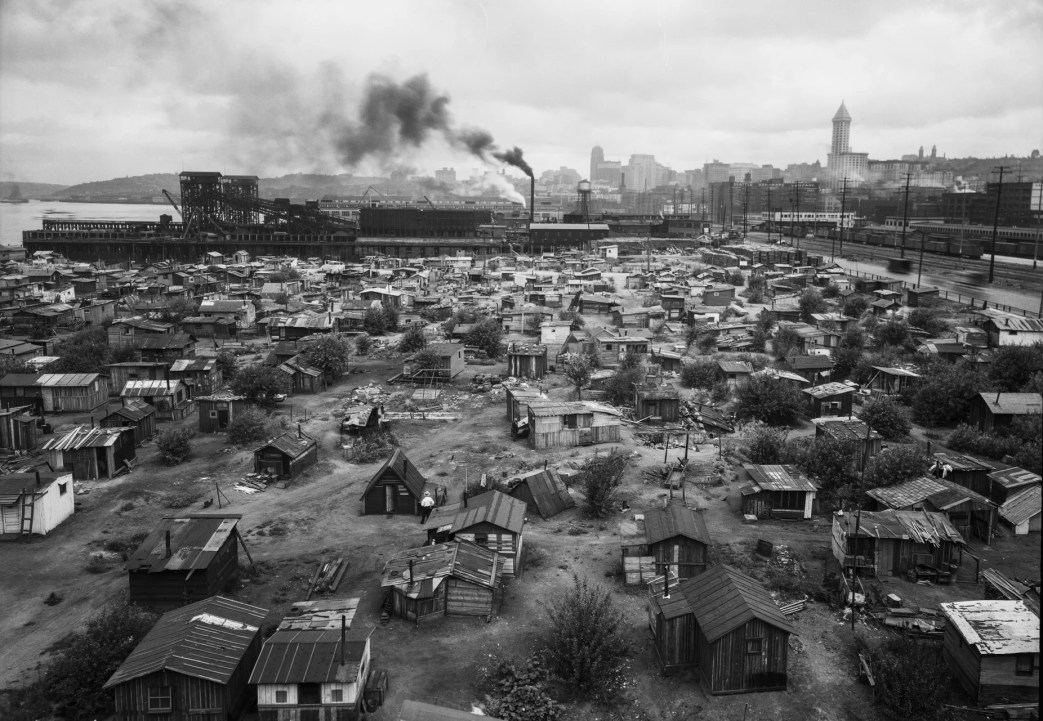

This is the challenge of the 13,000 families, representing 50,000 persons, in the Unemployed Citizens League of Seattle to the propertied class. Nor are these mere empty words, for since early last Fall when the League was organized, its members have been engaged in building a society within a state, which, considering the handicaps to be overcome, has proven that bankers and bosses are not needed to supply those who require commodities with what they need.

Started in a suburban district of the city by a group of labor college students and teachers with self-help and a public works program as its chief aim, the League established itself in 22 city districts in a short time. People who were cold to cut and dried programs for revolutionizing our social order were interested in cooperating to help themselves. They flocked into the locals and put themselves to work.

The cutting of wood for fuel on land donated by timber companies and the State was the first undertaking. Saws, axes, tools, trucks and gas were borrowed and begged from the city and private concerns. Workers were given a part of what they cut and the balance went to supply others who had no wood cutter in the family.

Next, expeditions were sent to scour the farms for surplus potatoes, fruits and vegetables. Thousands of tons were brought in. Then each local established a commissary for the distribution of its products. Fish from the surplus brought in by salmon and halibut boats was secured to the amount of thousands of tons. Much of it was frozen in the municipal cold storage plant for later use. Some food donations were made by local firms. / At che present time the League is handling 1,200 tons of wood per week, 100 tons of coal, 400 tons of food stuffs, and 300 tons of fruit. Local housing committees have made minor repairs on hundreds of dwellings donated rent free for the use of evicted families. The unemployed have contributed labor, free, in return for a certain period of occupancy. There are no central feeding stations but most of the commissaries have a kitchen which serves free meals to those working around the depot and in the shops.

While regarded at first with some suspicion by the city administration, the League was soon able to command respect and forced the City Council to reverse its proposal for a special unemployed wage scale of from $1.50 to $3.00 per day. The League demanded a minimum of $4.50 and this was adopted when a large delegation packed the city hall on this question.

This respect deepened later into recognition when the County Commissioners and the Mayor’s Unemployment Commission jointly agreed to distribute food purchased with public funds through the League commissaries. This is still continuing at the rate of approximately $150,000 per month. A little of this goes for gas, for hauling wood and truck parts.

The unique feature of this relief system is that all the investigation of applicants and checking in and out of rations is done by the unemployed themselves. All draw on the basis of the number of mouths to be fed. All able-bodied persons are expected to be available for two days’ work per week of 6 hours—at wood cutting, investigating, committee work, etc. All wood and food gathered is now turned into each commissary and rationed out to those in need on a “communistic’’ basis.

No one connected with the League receives any pay. All meeting places, such as churches, community club houses and store buildings for commissaries, shops, and garages are given rent-free by the owners. Small funds for incidental expenses are raised by dances and entertainments, but the League operates almost entirely without money. To expand its industrial program with the establishment of factories, where commodities will be made for the use of League members, not for sale, a drive is on now for a special fund of many thousands of dollars. Public moneys will be demanded and wealthy individuals will be asked to give. This will have a strong appeal as it will tend to make the unemployed self-supporting.

Each local is responsible for the proper operation of its commissary to the Central Federation of the League. This body in turn is responsible to the County Commissioners for a strict accounting of all food bought with public funds, but the League maintains itself as an independent body. The set-up of the League takes the local branch as the point of beginning. Committees on relief, housing, transportation, fuel, investigation, child welfare, garden, health, etc., take care of the needs of the members. Each local sends delegates to the Central Federation for the mapping out of general policy and other delegates to central committees on relief, housing, industrial operations etc. These act as a clearing house to co-ordinate local activities and avoid duplication and cross firing.

While the League started on a nonpolitical basis, the pressure of conditions last spring forced it to endorse candidates in the municipal election. Politicians rubbed their eyes in amazement the morning after when the full slate was elected. Three were men virtually unknown, who were conceded before the polling date, to have little chance of winning. Official attitude at once took a marked change for the better. A request by the League for the use of the Civic Auditorium for a mammoth mass meeting and free street car transportation was freely granted. (In the Fall this had been bluntly refused). The organized unemployed had proved that they were a force to be reckoned with.

Expands To Other Cities

In the last two months organization along similar lines has sprung up in adjacent cities and towns and in many county districts. Unemployed workers and deflated farmers are finding that they have a common problem and can go far together toward solving it. Self-help and the interchange of products will be a cardinal plank in the platform but emergency legislation and political action to put progressives in office will also have an important place. There is much talk of running an independent ticket in the coming State election. A state wide convention is being held, as this is written, to perfect and spread the movement in the Northwest.

The general program of the League, aside from its industrial self-employment feature, includes:

1. Full and adequate relief, at the expense of the county, state, and federal governments for every unemployed person.

2. Unemployment insurance along the lines proposed in the bill, which will be submitted by the League through the initiative to the voters at the Fall election.

3. No evictions from homes or apartments, because of inability to pay rent.

4. No light, water or gas shut-offs, because of inability to pay bills.

5. Lowering of legal interest rates.

6. All relief work on county and state jobs to be at a minimum rate of $4.50 per day, and done by day labor without the intervention of contractors.

7. A program of public improvements, city, state, and nation, to provide needed work.

8. A moratorium on taxes, mortgages and bank loans, where people are unable to make their payments.

9. Free medical, dental, burial, and hospitalization services for unemployed workers, needy farmers and their families.

10. Legislation to tax employers a fixed amount for each hour worked by any and every employee in excess of six hours in any day or more than 30 hours in any calendar week. The funds thus provided by such taxation to be used exclusively to care for the unemployed.

11. The five day week, and the six hour day in all public employment.

The development of the Seattle movement has demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt that the unemployed can be organized if they are approached as normal human beings with wants to be satisfied. They are not interested in radical philosophies, but will not balk at action which 1s revolutionary in its implication, if it seems to promise them something which they want. Their daily experience in working together and fighting for their bread and butter, develops solidarity and group consciousness and opens their eyes to the fundamental nature of a winning program.

What Seattle, Tacoma, and other Washington unemployed have done can be duplicated elsewhere if these points are kept in mind. Following are suggestions for procedure in any city or community:

Instructions

1. The work or organization may be undertaken by any group who have some understanding of the social factors involved in the unemployment problem.

2. A meeting of the unemployed, however poorly advertised, will draw a crowd. Contact churches, schools, community club halls, etc., for a free meeting place. At this meeting should be formed an organization committee to extend activities to other sections. The central idea is for the unemployed to go to work to produce their own necessities. This is a sound policy which will get the support of taxpayers and business men upon whom the relief burden is heavy. The cooperation of these classes is almost essential to success, as they own the resources and equipment which the unemployed need.

3. In this and subsequent organization meetings, stress the fact that the workers have produced all wealth heretofore and that now, being shut out from industry, they should again produce wealth for themselves using such idle machinery and land as is available.

4. The formation of small locals, close enough together to be in walking distance of the members is recommended. Two or three hundred is as large as a local should be. When they grow larger than that they should divide themselves and their districts to avoid becoming unwieldy and inefficient.

5. Upon the formation of a local, a president, secretary, relief committee and delegates for a Central Federation should be elected, and instructed in their duties. The relief committee should be urged to secure as soon as possible a vacant building for free use as a relief commissary. A store building is best, and craftsmen in the organization can make what repairs, painting, etc., is necessary.

6. Get a centrally located room or building, on the ground floor front if possible, for a central office.

7. The executive secretary should be the general overseer of all activity and, with his contact group, conduct relations of the organization with public officials, business men, etc., and should be chosen for these qualifications as well as his understanding of fundamental problems. The heads of all working departments should be chosen on their merits for the job in hand. Gardens should be under the direction of the best agriculturalist available in the organization, fuel operations in charge of a logger, if in the timber, or a construction man, if from wrecked buildings or bridges; clothing manufacture and repair shops supervised by a tailor and so on.

8. Contact with public officials should be made as soon as the organization reaches any considerable numbers. Lay the plan before them as a constructive business proposition which will lift the major portion of the public relief burden if it is rendered the aid necessary in its beginning, a money saver to county, city and business. Appeal for their cooperation and that of the press in getting the necessary land, tools, gas and equipment, with which to get into production in a modern manner. Later, when the mass of the unemployed are organized, pressure may be applied to the county to get temporary aid in the way of direct food relief for the local commissaries. This should be attempted only after adequate machinery has been perfected in the local and central relief committees for “investigation” requirements in the manner of community chest agencies. If this is done the league can establish its own standards as to what constitutes a needy family.

9. Avoid political entanglements, endorse no candidates in the beginning. Political policy can be worked out later after the organization has the members. Avoid alliances with relief agencies who promise cooperation with the idea of holding their well paid jobs. Stand for the independence of the League as the only constructive relief program and the support will be compelled to swing your way. Avoid money in the organization. Cash contributions, cash receipts from entertainment functions, relief funds from public sources should be handled by some prominent individual trusted and respected by all classes and dispersed according to instructions of League officers. No graft charges can then be made. Avoid any trading or selling of league products. These are produced for use and not for profit and must be consumed by members, not put on an already demoralized market to compete with established business and employed labor and alienate their sympathies with the unemployed. Turn all commodities into a central commissary and distribute them through local depots.

10. Establish a rule requiring each member to do his share of the work of the League—so many days each week in rotation. Avoid red flag waving. This cannot be a revolutionary organization. It must consist of all the unemployed and conform to the level of mass intelligence and raise that level by the example of deeds, not words.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v21n11-nov-1932-labor-age.pdf