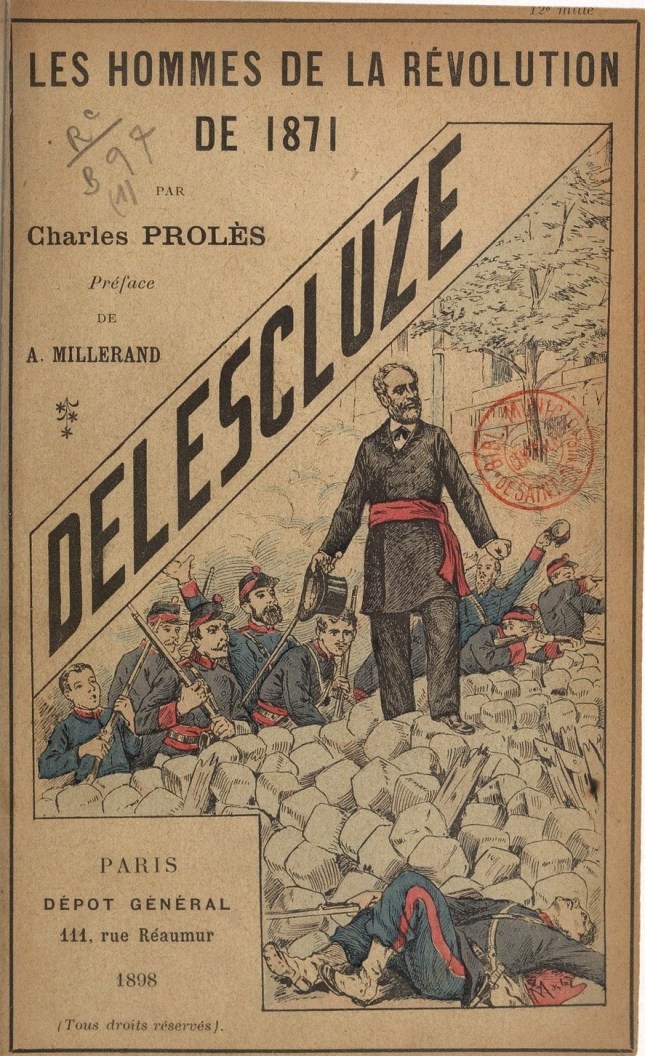

Seventeen years after his death on the barricade of Place Château-d’Eau, the military commander of the Commune is remembered.

‘Louis Charles Delescluze, Hero of the Commune of ‘71’ from Workmen’s Advocate (New Haven). Vol. 4 Nos. 11 & 12. March 24, 1888.

A Seasonable Retrospect–Lessons of the Parisian Uprising–Forecasting the Last Struggle–World’s Workers-A Hero’s Death.

The younger generation of the struggling proletariat–generations of proletarians come and go all too quickly–is so busily engaged in the everyday wringing for the attainment of its ideal of freedom, solidarity and justice for mankind, that there are few opportunities for many retrospect glances at the progressive phases of the revolution.

And yet there are periods in the recent past that live in the memory of the older comrades in the proletarian army, which may be referred to with profit for the valuable les- sons they teach and the incentive they bring for zeal and encouragement to further sacrifice and effort.

One of these periods is that of the Paris Commune of 1871 which, being a historical necessity, in more than a single instance, taught the proletarians of modern times that even under the most favorable circumstances of a moment, no lasting success may be hoped for, in the sense of social emancipation, as we understand it, as long as the purely material, economic conditions have not reached a certain development, and while in the minds of the masses, as in those of their leaders, there has not been developed a clearly defined knowledge of the only possible, success–promising revolutionary tendency. At the same time, both friends and foes of the labor movement should learn from the two months’ struggle of the Paris Commune to what extent the laboring masses are capable of displaying strength and heroic valor when they once have grasped the sword in the high hope of freeing themselves from their oppressors and exploiters for all time to come.

In the irresistible force which the brave communists developed in those memorable days lies a promise for the proletarians of today who battle with the weapons of reason and solidaric unity, of the inevitable ultimate victory, when, in the fulness of time and in the final effort, not only the proletarians of Paris, but of the whole civilized world, arise to deal at death blow at the rotten and tottering fabric of the reigning system. The experiences which the Paris Commune has bequeathed us, being probably the last of the kind which the modern proletariat had to go through before the final triumph, are of especial value, and it is therefore most appropriate if during the “ides of March” the older soldiers recall the story and relate it for the encouragement of their younger brothers.

During the Empire (salaried) writers even declare it was by and through the Empire with its frivolous and luxurious wastefulness) France’s industries developed magnificently. But the inseparable accompaniment of the capitalistic system of industry, the impoverishment of the masses, developed also; class interests were sharply outlined, and the way was paved for the reintroduction of the revolutionary ideas for which the “men of June,” the “victorious vanquished” had already died. Naturally, the progress of revolutionary agitation was somewhat obstructed by the sectarianism of the various socialistic “schools,” There were the followers of Louis Blanc, the Fourierites, the Proudhonites, the Socialists, and others, each of which wanted to increase its territory. The appearance of Marx’s “International” first promised, in the sixties, to bring more unity into the movement, and with its glorious motto of “Proletarians of all countries, unite,” had made rapid progress, when, all too soon, the war of 1870-71 brought the catastrophe. The defeat of the imperial armies at Sedan overthrew the Napoleonic throne, and for the third time the Republic was proclaimed. The subsequent warlike events apparently left it an open question as to whether the new French Republic should be a middle-class or proletarian, industrial one. Certain it was that the workingmen of the great industrial centers were not inclined to deliver the government over to the landlords and greedy bourgeoisie, without securing to the working classes a commanding position within it, which would pave the way for their eventual and absolute emancipation.

The landlords and the bourgeoisie certainly feared active and energetic measures in this direction by the working people, and this fear led to the reactionary elections for the National Congress in February, 1871, which gave the enemies of the proletariat courage to execute the perfidious trick against the Parisian workmen and an industrial republic. This consisted in the disarmament of the Paris National Guard, whose military power was feared above all.

The attempted carrying out of this perfidious plan led to the events of the eighteenth of March and the subsequent communal uprising.

The assertions made by opponents who falsified history that the events of the subsequent weeks were the doings of a few dozen of “professional agitators,” of the young International, Parisian “Club heroes” and revolutionists of the “old school,” are either deliberate libels or great errors. Every real revolutionary act of the Commune was due to the watchful activity of the Central Committee back of the Official Commune, and this Central Committee was elected by the workingmen and petit bourgeois of Paris, as far as they were enrolled according to city divisions in the National Guard. The Central Committee was formed of reputable artizans, intelligent and honest. Had the Official Commune been as well composed as the Central Committee, many a mistake would have been avoided; and had the real, intelligent working class been more represented in the leading body, while it would not have been victorious, it could not have heaped error upon error as it did. Of seventy members only twenty-five were workmen; the rest were small tradesmen who had sympathy for the cause, but no adequate knowledge of the labor question.

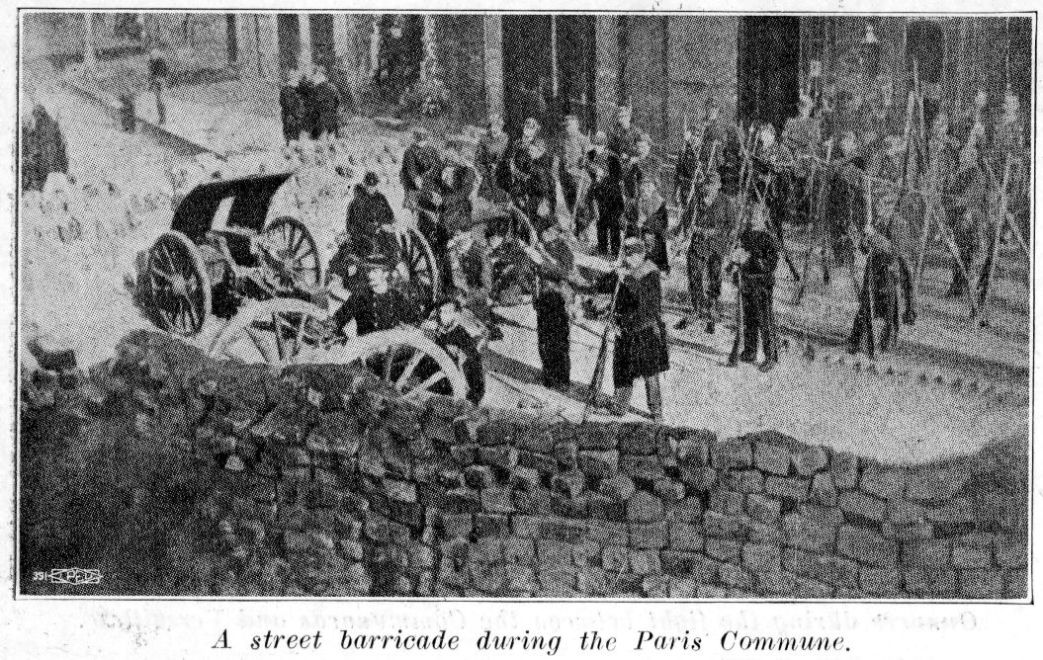

Malon and other clear-sighted Socialists, saw and warned against the untimely uprising, in vain. The brave working people were filled with the glowing fervor of battle, so intent upon doing their part, that fate had to take its course. These were the ones that won the first battle for the Commune, and these were they who, when all hope of success had fled, fought with wonderful valor against the Versailles hirelings and disputed their progress inch by inch, retreating only before superior numbers and arms. And these were massacred by thousands in cold blood by the revengeful bourgeoisie the following May.

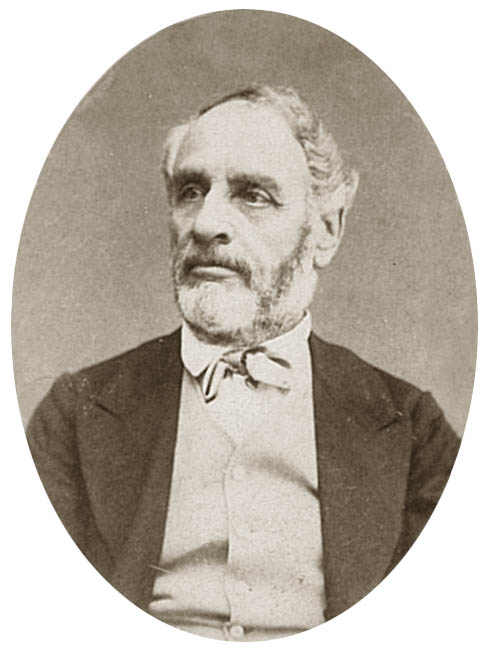

The Commune brought forward more than one noble figure, but none that are more worthy of remembrance and honor than LOUIS CHARLES DELESCLUZE, whose portrait adorns our columns. He was not a youth but a man with graying hair, become aged in the service of the revolution. He needed no invitation; “the people arose, the storm broke” and found him faithful and fearless at the head of the fighters. The citizens of his arondissement almost unanimously elected him to the Council of the Commune who placed him upon the Executive Committee and finally at the head of the Council of War. Wherever he was placed, obscurely or prominently, he proved himself careful, energetic, faithful and fearless, above all suspicion–an honest workman in the service of the people.

Did he err in his work? Perhaps. Even Delescluze was not infallible. But he was irreproachable as a man of character. Delescluze died the death of a hero in the last days of the struggle. He did not wish to survive the defeat of the Commune, An eye witness relates the circumstance as follows.

“At a quarter to seven o’clock we saw Delescluze, Jourde and about a hundred Communists marching in the direction of the Chateau d’Eau. Delescluze was dressed in his usual habit, black hat, black trousers and overcoat, the invisible red sash about his waist. He was unarmed, and walked with a cane. We followed at a short distance, when about fifty metres from the barricade the guards who accompanied him were scattered–the air was thick with flying projectiles. Delescluze, without looking to see that the others were with him, marched forward. He was the only living person on the street. When he came to the barricade he turned to the left and mounted the paving stones. For the last time we beheld the earnest, gray-bearded face turned towards death. Suddenly he disappeared A Versailles bullet had pierced his heart. He had confided his intention to no one, not even his nearest friends. Silently, his strict conscience only in confidence, did he step upon the barricade. The long labor of his life had exhausted him. He had but one breath and breathed it. The Versaillese sequestrated his corpse, but his memory will be buried in the hearts of the people. He lived only for justice–the talent, the conscience, the pole star of his life. To her he appealed, confessed her for thirty years in exile, in prison, under the scorn of his persecutors, regardless of the persecutions which broke his body. He fell at the side of the men of the people, to defend them. His reward was that when his hour came he might die in the bright sunlight with free hands and without being insulted by the sight of the hangman.”

He died a hero in the cause of labor.

The Workmen’s Advocate replaced the Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement and the English-language paper of the Socialist Labor Party originally published by the New Haven Trades Council, it became the official organ of SLP in November 1886 until absorbed into The People in 1891. The Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement, published in Detroit and New York City between 1879 and 1883, was one of several early attempts of the Socialist Labor Party to establish a regular English-language press by the largely German-speaking organization. Founded in the tumultuous year of 1877, the SLP emerged from the Workingmen’s Party of the United States, itself a product of a merger between trade union oriented Marxists and electorally oriented Lassalleans. Philip Van Patten, an English-speaking, US-born member was chosen the Corresponding Secretary as way to appeal outside of the world of German Socialism. The early 1880s saw a new wave of political German refugees, this time from Bismark’s Anti-Socialist Laws. The 1880s also saw the anarchist split from the SLP of Albert Parsons and those that would form the Revolutionary Socialist Labor Party, and be martyred in the Haymarket Affair. It was in this period of decline, with only around 2000 members as a high estimate, that the party’s English-language organ, Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement, appeared monthly from Detroit. After it collapsed in 1883, it was not until 1886 that the SLP had another English press, the Workingmen’s Advocate. It wasn’t until the establishment of The People in 1891 that the SLP, nearly 15 years after its founding, would have a stable, regular English-language paper.

PDF of issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90065027/1888-03-24/ed-1/seq-1/