The U.S. labor movement has never succeeded in a general organization of the South. The consequences of that failure have shaped U.S. politics for the worse since Reconstruction. Tess Huff reports on the Southern Industrial League conference held in Hendersonville, North Carolina in 1932 that brought together largely textile mill workers at a time of intense struggle in the region.

‘A Conference of Southern Workers’ by Tess Huff from Labor Age. Vol. 21 No. 8. August, 1932.

It is Sunday, July 25 in Hendersonville, North Carolina. The Southern Industrial League, organized by Lawrence Hogan a year ago, has met for its first conference. Sixty-five workers from Southern mill towns crowd the small room. It is the first conference of its kind in the South.

That conditions are terrible, the reports agree.

Story after story of wage-cuts, stretch-outs, speed-ups, lay-offs, pellagra, hunger, slavery, and signs of revolt, told by men and women who have grown up in the mills, many of them the worse off from hunger, put before the convention a cross-section picture of a vast, seething industry on the verge of eruption. The rank and file reports tacitly demanded an answer to a hard question: We can’t stand this much longer, what are we going to do?

“In High Point,” reports chairman Hogan, “where 6000 workers are striking, there is a wonderful spirit. The workers are flaming with revolt. The same conditions that hurled them from the mills to struggle with the bosses for a living are common in all the mills throughout the South.

“The textile industry has made more changes in the past five weeks than in the past five years. There have been more wage-cuts, more lay-offs, short time and piece work, in the past five weeks, than ever before. Out of 104 mills where I distributed the Shuttle I found only 4 mills running. The others were shut down entirely or working part time. In 9 mills things are ready to pop.

“In the print cloth mills the highest wage is $7.35 a week. The average is $2.50.”

“Look at Me!”’

A small man, underweight, who comes from a mill in ___ N.C. and whose name cannot be printed here, since he still has a job, makes this report:

“I’ve been 30 years in a cotton mill.

“Look at me.

“I weigh 128 pounds.

“I’m a fixer, I work 11 hours a night, and I’m the bossman’s slave. I get 27 cents an hour and I furnish my own tools. I make $7.45 a week. My helpers get 17 cents an hour and make $3.27 a week. We have to take what we can get or be kicked out.

“The sanitation is unbelievable. The floors have not been scrubbed since 1904. That’s a fact. The tobacco and snuff spit is caked so I have to scrape it away before I can get to the nuts.

“The toilets are full of maggots and the odor is terrible.

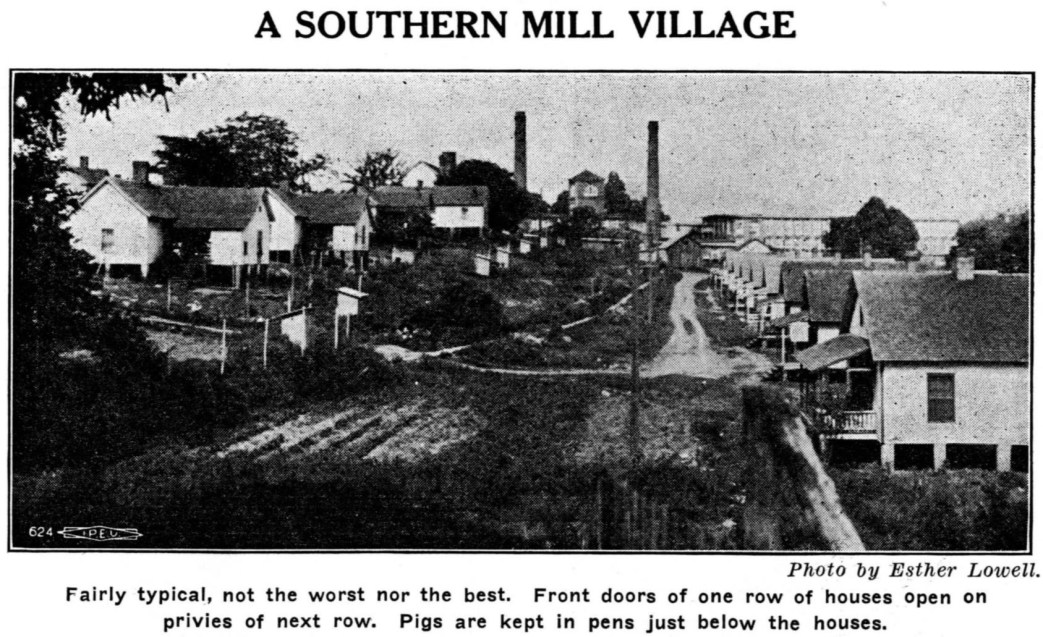

“The doctors won’t come without the money and school children are infected and there is lots of pellagra. We tried to get the State Board of Health to do something about the 6 mills in the village. There is much sickness. About the only time the people can bathe is when it rains.

“I can’t make a living. We pay 90 cents rent a week for a 3 room shack and my wife and children are almost naked. Do you think they get medical attention? No, friends, I’m telling you about how the workers live in the South now.

“The boss wants to keep us blind. My boss, he used to be a preacher, but he knows how to get more work out of men.

“The South needs a union and my people who fought against the union 20 or 30 years ago are now ready to fight for it. We are waking up, friends, and we will learn to stick together.”

The speaker sat down. They said he was a real Jimmy Higgins. By some: kind of proletarian magic, he had seen humor in tragedy, and his speech, magic-like, lightened the atmosphere in the room, warmed all hearts. Certainly workers like this man, one felt, will build a Southern labor movement before they have finished.

“But Still Paying Dividends”

A young woman, slender, tall and blue-eyed, reports. Her name is Beulah Carter and she is all-Southern even to the low musical drawl in her voice. She studied trade union tactics at Brookwood and for two months she has been organizing hosiery workers.

She tells about Durham, N. C.

“Five-hundred people are applying every day for relief. People are living 7 days on 75 cents and they told me that pellagra is increasing.

‘In Durham the mills are running 3 days every other week; in West Durham they run 2 or 3 days a week; and the workers make $5 and $6 a week. Full fashioned hosiery workers who used to make $50 and $60 a week are working for $7 and $8. But the silk mills in Durham are still paying dividends.

“Cigarette workers are working regularly but they are worked to death. They work 3 nights a week till 12 o’clock. They had 2 or 3 cuts; the girls are making $7 and $8 a week, the men $12 and $15.

“Nearly all building trades unions are out of existence. They had a meeting and I went. Two men were there. I went to a meeting of the Plumbers’ Union and one man showed up. The Painters are out of existence. The Barbers have the only functioning union in the city.”

Another woman reports. She tells about working 10 hours a day 2 or 3 days a week. They had a big cut in 1931. She has been working in a hosiery mill for 3 years and is afraid she will lose her job if her name is printed.

High Point

Three women from High Point, where a few days ago six thousand textile workers uprose in a city-wide spontaneous strike, including Negro house servants, such was the spirit, tell about wages cut so low that they can’t be cut any more, and of black conditions that precipitated the strike.

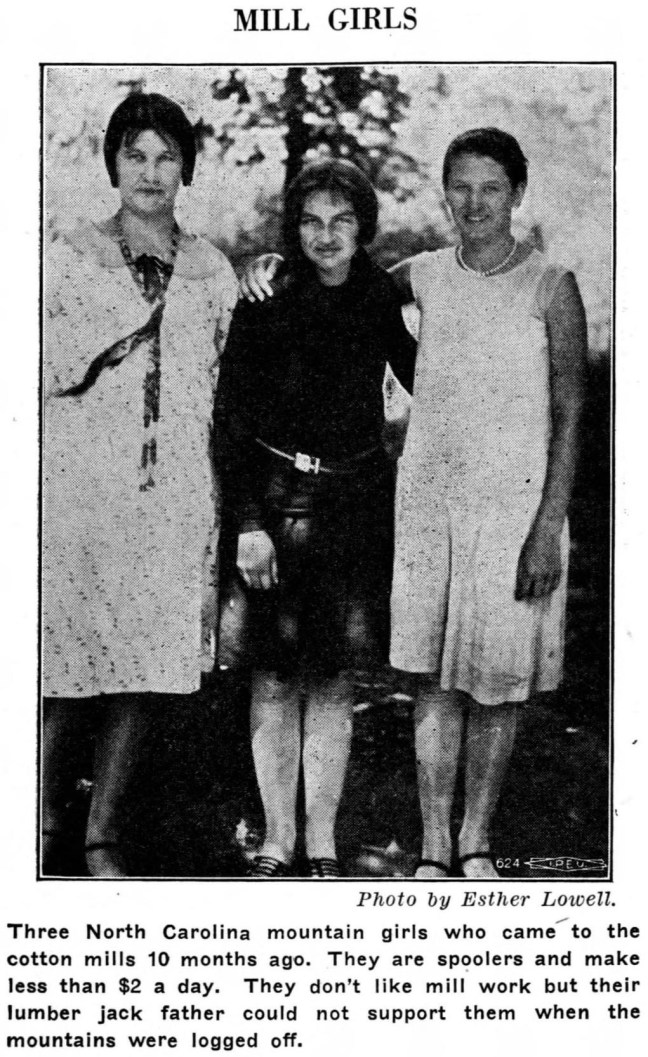

“The girls can’t earn enough and they live in crowded rooms. They come home so tired they can’t talk. They are humans, they want some fun in life. One girl ran away because she couldn’t pay her board.

“They had 2 cuts this spring, 4 in some departments. I have been out of work over a year.”

The second woman speaks:

“There are 32 mills and in the mill where I worked 58 women have to use one toilet. There are no windows in the building and we had light globes the size of a dollar to work by. The ventilation was not much. Cardboard cuspidors are scattered about and they sweep the mill once a week. Just one colored man is supposed to clean the whole mill.

“When an order comes in they work you day and night.

“They cut the loopers $1 a hundred in November. The workers make $7 and $8 a week.

“Northern people own some of the 32 mills and local people own the others. They live in $65,000 and $85,000 homes.

“For 10 months I have not found work.”

Like the first woman reporting from High Point, the speaker wants her name kept secret, not because she has work, as in the other cases, but because she has no work, and is seeking for work!

The third hosiery worker puts the finishing touches to the background of the strike.

“In the neighborhood where I live I know men and women who have been working for about 50 cents a day, $2 or $3 a week. Full time would not give us a good living. Folders have been cut 3 or 4 times in the last year. They have cut wages so low they can’t cut them any more.”

Marion

Reports from Marion, N. C., like those from other mill towns, show the workers in the third year of the depression caught in a web of monstrous circumstances, the insane vampire, Capitalism, sucking the blood of workers and children.

Four wage cuts since the 1929 Marion strike, wherein 6 strikers were murdered by the state, leave the workers earning an average of $3.50 a week, the delegates are told by a Southern Brookwood graduate, unemployed. Sanitation, however, he says ironically, is better since the strike.

“A baby died,” a woman from East Marion reports, “because the young mother was told if she didn’t get to the mill on time she’d lose her job. There is no relief available and the people are starving.

“They won’t give me a job since the 1929 strike. Before that I was in the mills 7 years. The windows are all kept down and on cold days we come out sweating. The toilets are flushed 2 or 3 times a day and the drinking water is in the same room with the toilets.

“The owners tell everybody the average wage is $16, but the foremen, who used to get that, are now taking cuts, looking for jobs, and pawning their autos.

“The machines start at 5:40 in the morning, but they blow the work whistles at 7 o’clock to make outsiders think the mills start at that time. The workers have to get up early if they have jobs. And they give us 30 minutes for lunch, sometimes they double up and work through lunch. They don’t allow us to stop a minute.”

Efficiency Experts.

Two men came down from New York to Greensboro last year to make a time study of the workers. For several days they stood over the workers, watches in hand. Twenty mothers, some of them with as much as 18 years service, were fired from one mill because they were too slow. The Bedeaux system was installed. One girl had her wages cut under the speed-up system 50 per cent for the same work.

“We couldn’t stand it,” the delegate, a woman from Greensboro, reports, “and on February 28 we walked out. Finally we had to go back, we agreed to a 12 1/4 per cent cut, but there was to be no discrimination. Inside 3 weeks the strike committee was fired. We struck again, about 400 of us. The picket line got out a few more. They took the committee back and we returned to work.”

A man from Caroleen who has five children tells about earning $3.50 and $4 a week.

“A hundred of my friends are in the same boat. I had to drop my insurance after paying on it for 5 years. I started a group last fall, I have 12 key people now, and I’m feeling around for more. The boss has a lot of kinfolks in the mill making it hard to spread union work.”

Reports from Forest City where wages were chopped off 35 per cent last November put the number of unemployed at 300. In Hickory, where the U.T.W. still has a charter but not much life, the boys want to start a union. Other reports are the same. Everywhere there is misery and the workers know there is misery and they are looking about, hoping, questioning: We can’t stand it much longer, what are we to do?

Bill Reich from the North Carolina Pioneer Youth Camp speaks. He tells the conference that the intellectuals in America are today interested in the labor movement, but that they see things from above, like a man looking through a microscope, and that the real labor movement will have to come from the workers themselves. The workers are held back by the capitalist movies, newspapers, public schools, which, he points out, spread an antilabor philosophy, and by poor food, poor housing. The crying need is for workers’ education.

Irene Hogan speaks. She tells about how oppressed workers in 14-16th century England came to America for freedom. “Time rolled on, industry came, America grew, but today—our cities are filled with hungry men. The huge fortunes, the billions spent preparing for war! This is the challenge we face. It is our job to do away with a system that neglects the workers.

Larry Hogan Sums Up

The chairman, Larry Hogan, sums up:

“These conditions in the South, comrades, come from a lack of organization. The A. F. of L. has been in the South with a million dollar organizing program, but what are the results? Conditions speak for themselves.

“We must build up a program of workers’ education. Pick key men, train them, develop them for leadership. And the movement must come from the workers. Some organizations are not interested because the workers have no money to pay dues.

“We formed the Southern Industrial League with the CPLA to instruct in forming unions, to develop leadership, and to teach a real workers’ outlook on life, economic and political.

“The workers have never had the right kind of literature. The Shuttle is an attempt in this direction. The Shuttle develops the expression of the workers. Always moving to and fro—always carrying something with it—a sure-go Southern textile newspaper. But we must make it better, we must add others.

“I use the whirlwind system of distribution. Making about 40 through a town I toss a bundle of Shuttles into the air, the wind whips them away, scatters them, and the mill workers, who have learned to expect them, run out and pick them up. I need helpers. We must get them to unemployed Greensboro workers.

“The Southern Industrial League and the CPLA are here to help you, glad to cooperate in organizing and in strikes. Send for me—I’ll come humping on Hoover’s bus. (That’s what we call freight trains out here.) I’ll help you get out a sheet like the Shuttle. I’ll help you start classes. That’s the main thing now, start small groups. The workers are ripe for organization. The unemployed are going to play an important role. Everybody is tired of the Federal Farm Board flour, it’s full of weevils, we can’t live on that.”

He tells about the Progressive Farmers’ League which recently staged a mass protest against the sale of land for taxes. The farmers have debates, labor plays, classes, current events discussions. The League was organized by Hogan.

A. J. Muste, executive chairman of the CPLA, conducted the discussion and speaks in conclusion:

“There is no easy way to build the labor movement. It cannot be done without evictions, hunger, strikes, jail, and the policeman’s club. We have plenty good starters, we need good finishers. It will take courage, it will take endurance, it will take patience. A long struggle is often necessary before results are gained.

“There are things you can do— talk to others, form small groups, distribute literature, report to Larry Hogan what’s happening in your field.

“We shouldn’t all be talkers, we need people who will do something about it.”

Some delegates who were expected didn’t get to the conference. One man caught and tore his last shirt in a machine. One was sick from pellagra. Others, it was reported, were detained by sores caused by muddy stagnant water sprayed through humidifiers in the mills.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v21n08-aug-1932-labor-age.pdf