Legendary journalist Agnes Smedley with an early report on the activities of the 5th Red Army.

‘A Chinese Red Army’ by Agnes Smedley from New Masses. Vol. 6 No. 8. January, 1931.

A young student from a Shanghai university who went to Yochow, Hunan, for his last summer vacation, arrived in his native home a few hours after it had been captured by the 5th Red Army. This student has now written an account of his experiences which, though quite superficial, is the first unbiased account of events taking place in cities or districts captured by the Communist armies in central China.

When he approached Hankow by a river steamer, he threw overboard all modern magazines containing articles on any economic or social subject. Not that he was a Communist or had Communist magazines — but Hankow militarists shoot men for less reason than reading economic articles. The student changed boats at Hankow and reached Chili-shan, where the boat halted for a few hours because they heard shooting in Yochow, two miles away. Nobody knew what had happened, but they thought that perhaps the troops of Ho Chien, the Hunan war-lord, had revolted, or that the “Iron Army” had perhaps returned and captured the city. At last the steamer reached Yochow, and the student left all his baggage on the boat, hid in the grass the few literary magazines of Left writers that he still had with him, and started home. He had spent five days on the steamer, travelling third class, and was dirty and tired. As he entered the gates of the city, he met a vegetable seller and asked: “Is it safe for me to enter this city?” The vegetable seller replied: “Yes — have you just been released from prison?” “No,” the student replied, “I have just come by boat from Shanghai — what do you mean by prison?” The vegetable seller: “The Red Army has captured this city and all prisoners have been released.” The student: “Is the city being looted?” Vegetable seller: “No. Some shops have opened their doors and carry on their business as usual.” The students narrative, in his own words, continues:

“I said good-bye to the vegetable seller and walked toward my home. I met many Red soldiers walking through the street. They were young and their uniforms were just the same as those of Government troops, except that each one had a red sign on the left arm. I was unmolested until I put on my long coat which made me look like a bourgeois. Then the Red soldiers turned to look at me with dark glances, and I was suddenly caught by one of them. ‘What are you doing here?’ he asked. I replied that I had just come from the boat. ‘Well, come with me he said, and he led me to a building and stood me before another Red soldier and said: ‘Comrade Captain— a man has been caught.’

“The officer, who looked just like the other soldiers, said: ‘Sit down, please,’ and when I said ‘thank you’ and sat down, he sat down also, facing me.

“‘What is your business?’ he began.

“‘I am a student studying in the University of Shanghai. I just came from the boat. He asked for evidence, and I showed him my medal from the university. He then remarked: “You are a member of the intellectual class. Of course you are quite clear about our work. What is your attitude? Will you please tell me?’

“I explained to him what I thought and read and then told him that I had left my baggage on the boat and some books in the grass on the river bank. I asked to be permitted to bring these things. He said ‘all right’ and took out a small note book and using his leg to write on, wrote:

“‘This student is just back from Shanghai and he is quite sympathetic with our work. Please let him pass. Note: This passport is effective for 30 minutes. Signed by — Captain of the 5th Red Army. July 4th, 1:30 p.m.

“I hurried to the river bank and took my baggage which was in the possession of a friend, found my magazines in the grass and returned to the city without fear. My friend went with me. The streets were filled with small traders, workers, and poor men. They were not afraid of anything, because the Red armies never capture poor men and force them into military service as do Government armies. A Red officer saw us and came up to me and spoke: ‘Do you know what kind of troops we are?’ ‘Yes, I know’ I replied. He then said: ‘We are of the Red Army and the Red Army is under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party. We are called Communist-bandits — do you understand?’ He smiled when he said ‘Communist-bandits’ and watched my face. I smiled also and replied: ‘Yes. Communist-bandits — I know.’ I then showed him my pass good for 30 minutes. He read it and then walked down the street with me. A Red soldier walked by his side and listened closely. This Red soldier finally exclaimed: ‘I do not think he is a good man — perhaps he does not understand the real meaning of what you said.’ The officer watched me and said nothing. I asked his name, and told him mine and of my studies in Shanghai. He asked: ‘Tell us about the present situation in Shanghai; our life is very fierce and we are always moving and fighting from place to place. We can get no newspapers.’

“I told him that the movement in the foreign concessions in support of the Red armies was quite strong and that the intellectuals had gone to the Left during the past two years, and that they publish many books and magazines on the social sciences.

“‘How about this League of Left-Wing Writers?’

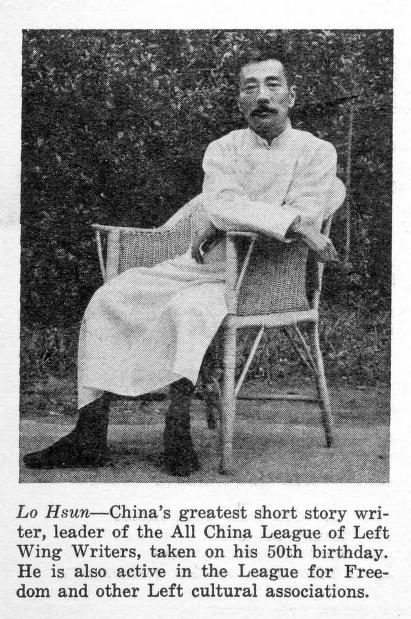

“‘Many writers have gone into it, and even the great Lu Hsun is a member.” (Lu Hsun is China’s greatest short-story writer.)

“‘Do you know about the Shanghai Pao (a Communist daily suppressed many months before)?’ I told him I knew it but that it had been suppressed and the Red Flag Daily took its place.

“We passed the magistrate’s court. Red soldiers were guarding it. We passed the empty prison and saw that the doors had been smashed to pieces. He told me of the Communist prisoners who had been released — they had been in shackles for months and many had died of disease and torture. The other prisoners were poor men imprisoned by the rich. We talked until my pass reached its time limit, but then he lifted his knee and wrote me another that was valid for two hours. He then asked me to come with him to headquarters. Turning over the pass and my baggage to my friend, I told him to go home, while I went with the officer. We passed through crowds of small traders, workers, ricksha men, peddlers and coolies who seemed happy and excited. All walls and doors throughout the city were covered with slogans painted in white: Workers and peasants, unite! Protect the free trade of poor traders! Poor men never fight poor men! Protect the Soviet army of workers and peasants! Carry out the land revolution l Establish the Soviet of Hunan, Hupeh, and Kiangsi! The officer explained: ‘We have propaganda corps, and after we capture a city, it must be covered with slogans within one hour.’

“The Red Army headquarters was in a primary school. There I was introduced to a young man about 30 years of age, head of the office. After listening to the officer, he looked at me for a long time and then said:

“‘If you can study in a university, you are at least a petit bourgeois. I also came from that class. But the economic background of our class is quite different from that of the proletariat. About all the petit bourgeois can do is to give sympathy to the proletariat.’ We talked further and he said: ‘The aim of the present revolution is to release the workers and peasants from the fierce oppression of the Kuomintang and the imperialists. To do this, our first task is to destroy the Nanking government.’ Later he said: ‘We are newcomers in this city and unfamiliar with local conditions. We eagerly hope that you will help us arrest the rotten gentry and reactionaries and the local rowdies.’

“At five o’clock I went home to greet my mother. She is an old lady of sixty and we have always been poor. ‘This morning the Reds held mass meetings everywhere/ she told me in excitement. ‘They told us what they were trying to do — to help the poor, to free the workers and peasants! But they are going to leave within two days!’ My old mother had gone to the mass meetings!

“While the Red Army was in our city it burned down the headquarters of the magistrate and the tax office, and no document was left. The Yu Cheng Ching jewelry shop was the only shop burned. It closed its doors when the Red Army asked it to contribute to the revolution. And do the soldiers broke down the door and shouted to the ricksha coolies and other poor men in the streets, saying: ‘Come — go into this rich man’s shop and take everything you need. Come — this is your only opportunity to get enough to live on until we come again.’ The poor men went in and carried out everything from the shop and divided it. The Red soldiers stood at the doors, but they took nothing for themselves, for this is forbidden them.

“The Red soldiers went to all the big rice shops in the city and forced them to post new price lists on all their doors. These notices read:

Order of the Headquarters of the Political Bureau of the 5th Red Army: The responsibility of the Red Army is to free the masses from their suffering and to help them to happiness. Now all food and clothing is kept at such high prices that the masses starve. We have now set prices for food and clothing and any violation of these prices is forbidden. All traders are strictly forbidden to hide their rice, or to change these prices. “Then followed a list of the five principal articles of food and fuel, rice, cereals, salt, lard, kerosene. Rice was priced at $2 per picul, although they had been selling it at from $8 to $10 before.

“I talked with crowds of people in all the streets. Everywhere I heard these words: ‘I speak from my heart — the Reds are good.’ No man was afraid to be pressed into military service, and when they worked for the Red Army they were paid $1 a day. The Red Army did not live in the homes of the people as do government troops, nor did they demand food and pay nothing.

“An old peasant from a village who had come to Yochow to sell lumber told me a story. There was a lazy, well-to-do man in his village, he said, but this man was kind to the poor. When the Red Army took the village, this man was imprisoned. His old wife and relatives went to Red Army headquarters and pleaded for his release, saying he was not a bad man because he had always shared his money and food with the poor. The Red officers told them that if they could bring eighty peasants from the village to witness the truth of their claims and to guarantee his future good conduct, they would believe. After a while the eighty farmers actually came and testified that the man was useless and rich, but, unlike other rich men, he had always shared money and food with the poor. The Red Army released the man. He was astounded to hear that poor peasants who hardly had a rag to their backs had enough power to secure his release. And he stood, held his fat sides, and laughed in his astonishment.

“After a few days the Red Army left Yochow, retreating before the well-armed government troops. The white terror began. The prison doors were repaired and the prison was again filled with the poor. All workers and peasants were suspected because they had done nothing against the Communists. Each day militarists caught suspected men and shot them or hacked their heads off in the public streets. The merchants raised their prices again and only those with a lot of money could afford to eat as much as they needed. The Red Army was gone — but at the end of August when I left Yochow, their slogans were still written on all the city walls, and on all the buildings. It would take months for the government troops to wash them off, and they are too lazy. When I left for Shanghai, I could read from a long distance the slogan on a wall — Establish the Soviet Government of Hunan, Hupeh and Kiangsi!”

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1931/v06n08-jan-1931-New-Masses.pdf