A valuable article by David Ivon Jones explaining the reasons for, possible dangers, and early operation of the ‘Tax in Kind’ on the peasantry that inaugurated the New Economic Policy.

‘The Soviet and the Peasant’ by David Ivon Jones from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 3 No. 48. July 5, 1923.

The Decree on the Unified Agricultural Tax.

Every day the Moscow newspapers give reports of the prospects for the next harvest, which appear to be increasingly favorable as the summer progresses.

This year’s harvest is being produced under altogether new conditions. A new spirit pervades the village. New relations are created between the city and the country, between the town proletariat and the peasantry.

It was Lenin himself who, at the beginning of the year, first pointed out how the link between the proletariat and the peasant could be strengthened. He proposed that every branch of the party in the towns should take over responsibility for the cultural needs of a village or volost. This idea has since been taken up on a very wide scale, and not only Party branches, but factories have also “adopted” villages, supplying not only books, newspapers, and propaganda material, but repairing the ploughs and harrows of the village. “Smeichka” (Lenin’s word for “Link” or bond with the peasantry), has become a general slogan. And now, when workers are everywhere going off to the country for their annual holidays, they go armed by their Branch secretary with propaganda material and information about the New Unified Agricultural Tax.

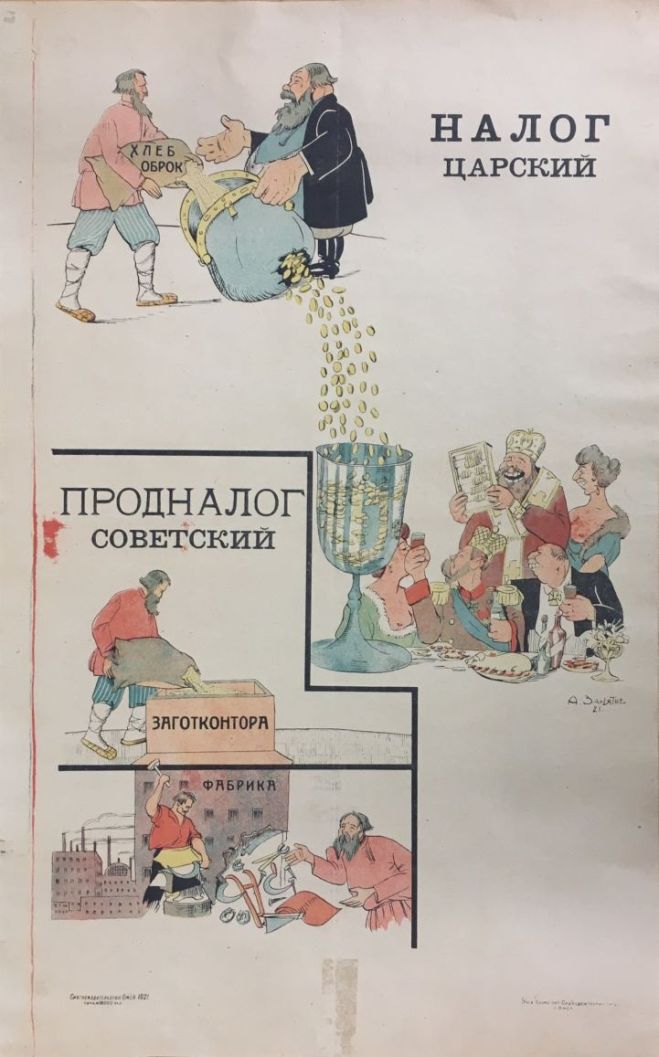

Trotsky not long ago referred to the difficult situation of the peasant owing to the low price of bread compared with the prices of industrial products. He said that the ideological “Smeichka” must have an economic basis. This economic basis has been enormously strengthened by the recent decree on the unification of all the taxes on the peasantry into one annual agricultural tax.

Up to the Twelfth Congress of the Communist Party the peasants, in addition to the tax in kind, were levied a series of other taxes for local and central needs. The peasants complained that harvest came only once a year, but the tax collector called in and out of season. And this caused them considerable inconvenience and no little irritation.

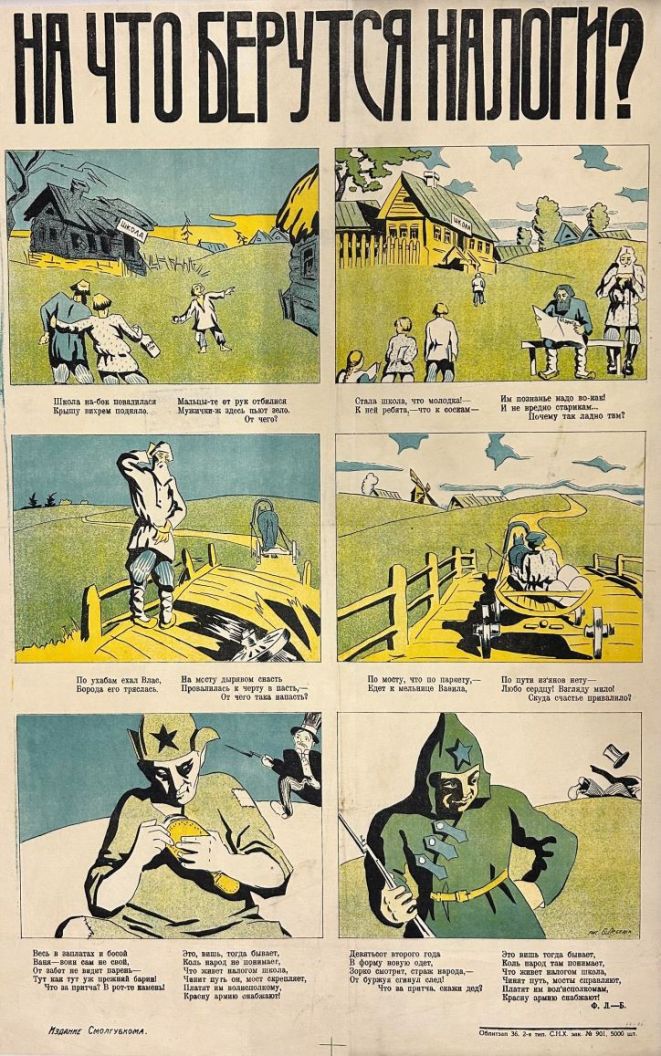

The Party Congress adopted the principle of the One Unified Tax; and the Government Decree has since been issued. The peasant will pay a tax once a year only from his harvest. All other payments which the volost or the village may require for local needs rank only as “collections”. All taxes on the peasantry, except the Unified Agricultural Tax, are declared illegal. Percentages will be retained by the Provincial Soviets for Schools, hospitals, bridges and roads.

The new tax has ceased to be essentially a Tax in Kind. The right is given to every peasant to pay in money according to the official prices fixed for wheat and rye units. But the tax is nevertheless fixed in units of wheat and rye, according to the prevailing crop in the locality. Certain areas will be marked out where the tax will be payable only in cash; that is, in industrial provinces where the peasant can quickly realise on his harvest. Other provinces will pay partly in cash and partly in kind. Thus the transition is begun of a general cash payment of taxes. Meanwhile the payment in kind is still necessary for the convenience of many peasants, and also in order to supply the needs of the Red Army and the Children’s Homes, thus saving the Government from having to compete in the market for prime necessaries.

The Tax in Kind imposed a certain amount of compulsion on the peasant to produce the specific products required by the Government. The new decree removes the last vestiges of compulsion. The peasant is given full freedom to choose the crop which appears to him the most lucrative.

“Ability to Pay”.

In the Decree on the Unified Tax the principle of “ability to pay” is given ideal form. No less than 396 categories of taxpayers have been fixed according to their ability to pay. This looks very complicated. But the principle is so simple that every peasant can see from the table to what category he belongs.

First of all, the decree starts off with the number of “eaters” in a family. That is, the tax is less as the number of eaters” per dessyatin is more. Thus we have nine grades of taxability, starting with farms of a quarter of a dessyatin per “eater” up to farms with three dessyatins and over per “eater”. Then we have four vertical divisions. Poor peasants without working animals or horned cattle must obviously pay less. Thus, column one shows taxpayers without horned cattle, column two, those with one cow, and so on. Thus we have a table with 36 (9X4) categories of taxpayers.

But suppose the harvest is poor. Or suppose that it is a very good one. Obviously you cannot take so many puds of wheat off a dessyatin of bad harvest and good harvest alike. So we are given eleven grades of crops, starting from crops up to 25 puds per dessyatin, up to crops of over 101 puds per dessyatin.

And so the above little table of 36 categories is repeated eleven times, making 396 arguments against the tyranny of formal democracy.

For example, one sees at a glance that a family without cattle, with half a dessyatin of land per eater, and less than 35 puds of crop per dessyatin, pays no tax at all. And a similar family with a quarter of a dessyatin of land per eater is exempted from tax right up to a crop of 45 puds per dessyatin; and even when it has a crop of 50 puds per dessyatin it only starts paying at the rate of ten pounds of rye per dessyatin; whereas its neighbour with a similar crop having more than four cows and more than three dessyatins per eater, pays a tax of 13 puds, 25 pounds per dessyatin.

Looking down the columns we see that the highest amount paid by the poorest category is five puds per dessyatin. That occurs when it has a crop of more than 100 puds per dessyatin. With a crop like this the highest category pays a tax of 25 puds, 10 pounds per dessyatin, about a quarter of the crop.

Of course, it must not be forgotten that this includes not only fax, but actually rent of land, which belongs to the people as a whole. In fact, here we have the Single Tax for the first time applied, not as a panacea for all the ills of society, but as the partial measure that it really is.

The Third Covenant.

Kamenev has called this new Unified Tax the Third Great Covenant of the proletariat with the peasantry. The first was the October Covenant socialising the land. Then came the 1921 covenant inaugurating the New Economic Policy with the Tax in Kind; and now the Unified Agricultural Tax, abolishing the last vestiges of expropriatory measures towards the peasants. To those whose minds are still dominated by utopian conceptions of Socialism, these three covenants represent stages through which the tide of revolution has rolled backward. To the petty bourgeois Socialist, whose class is pressed down by the money lender, money is naturally the root of all evil, And the transition of Soviet economy from simple barter and transactions in kind seem to him and to the uninitiated bourgeois to be steps backward from Socialism.

But the first period of the New Economic Policy has taught the Communist that the money system, when controlled by a Proletarian State, is one of the most useful devices known to social science. Without it no adequate system of accounting and control can be thought of. And if money, with all its concomitants of banking, taxation, etc., becomes under a capitalist government the agent of capitalist accumulation, leading to vast combines controlling the lives of millions for private profit; so, under a proletarian regime, this same money, hitherto so much maligned, through Soviet industry, Soviet banks and Soviet taxes, becomes the agent of Socialist accumulation, leading all surplus wealth into the service of the proletariat.

The writer met a comrade the other day who belonged to an agricultural commune. He was one of a deputation to the Commissary of Lands, and was in a cheerful mood. This deputation bore documents from the Provincial Soviet showing that the Commune had stuck together through the supreme test of the Great Famine. The Commissary of Land had on the strength of this given a cheque on the State Bank for a loan to the commune–secured on the movable property–to construct an irrigation system which would increase the prosperity of the commune five-fold. This is one of the many ways in which Soviet finance is helping the growth of Socialist production.

Is the Land Really Socialised?

The question that most often arises in the mind of the Communist abroad is: How far is the principle of the Socialisation of the Land a real one; or how far has this principle been made merely nominal by the inveterate private property instincts of the peasants?

Answers to this question crowd upon the mind as one reads the handbook on the Land Code, recently issued by the Land Department in the form of simple questions and answers for the peasants.

The Henry George theory of the Single Tax, which sought to prove that free land was the only remedy for social inequality, has been concretely disproved in Russia. The Russian peasantry has free land. But free land has not abolished classes within the peasantry, and a state of friction exists between the various strata of poor, middle and “kulak” peasants. The vital difference between them is not in the area of land they occupy, but in the movable capital, implements, horses and cattle which they own. The “horseless” peasantry is a term often used for the big mass of poorer peasants standing solidly behind the Soviets. Recently there was a congress of these propertyless peasants in the Ukraine organised by the Party.

While the Soviet Government has to allow the conditions causing this economic struggle (free trade and exchange, even the right of the “kulaks” to hire labour, etc.), in order to develop production, at the same time it takes part in this struggle on the side of the poorer peasants by mobilizing them into political activity, urging them on by propaganda and stimulative legislation to stand up, organise, co-operate, unite against the same “kulak” class which the Soviet must perforce allow to exist by the very character of the money system.

And what is the grand weapon at the command of the “poorer” peasantry in this struggle? The Social ownership of land. And the struggle leads directly towards the social use of land as its inevitable solution. The hope of the poorer peasants is in communal production. And for this the whole machinery of the Government, its finances, banks, co-operatives, organisers, are at their disposal, as soon as they can muster up sufficient spirit of organisation and co-operation to break with their old individualistic form of production and march forward. The Kulak class is strongest in the Ukraine. A report in the “Pravda” in March mentioned the enormous growth of collective farming in that area, and placed the number of Agricultural collectives at no less than four thousand.

Only the Proletariat can free the Land.

But free land is a mere day-dream without the dictatorship of the proletariat. In a government of bankers or even in a government of peasants, “free land” can only mean freedom to sell to the highest bidder or mortgage up to the biggest moneylender.

Marx’s “Eighteenth Brumaire” describes how the peasantry of France had been wholly mortgaged up to Paris finance, and therefore did what Paris finance bade them to, namely to vote the third Napoleon into power.

Encompassed by capitalist states, it is clear that the peasant can only remain a free peasant by leaning upon the proletariat, by supporting a regime which denies the very principle of peasant economy and all private property economy for its basis. The Land Code lays it down clearly for peasants and “nepmen” alike to understand that no one can sell, give, mortgage, or bequeath land, and that all such acts are not only void but punishable.

Neither can any peasant having right to land as a member of a village community waive such right in any ones favour for any valuable consideration whatsoever.

The new bourgeoisie would like to get its roots into the land as the one grand immovable security. In every transaction between him and the peasant involving the need for credit, the nepman is brought up against the Social Ownership of land. No People’s Court would recognize a bond on the land. Rather it would punish the bondholder. And there is a mass of young peasants and poor peasants too interested in their common right to the land to allow such a deal to go through unchallenged. Thus the New Economic Policy has strengthened the principle of the Social Ownership of land.

But the peasants need for credit must be met. And the Proletarian Government is itself stepping into the place of the moneylender by the formation of Peasant Credit Banks with capital running into millions of gold roubles, in which the State institutions are the largest shareholders, drawing in also a certain amount of shares from the savings of the peasants and the nepmen”, who in this and other ways are made to feed the State Bank of the Soviet with their surpluses.

According to the Land Code, the land of a “dvor” or farm belongs to every member of the family and not to the head of the family only. All ages and sexes have their share of the land, although they only enter into full rights of disposing of it at the age of eighteen. The name of the manager must be registered with the Village Soviet. It is not an immutable rule that the father of the family shall be the manager of the farm. If the other members of the family have reason to complain that the farm is suffering from chronic mismanagement, another member of the family of either sex, may be appointed.

Three years disuse of land means forfeiture of all right to it. A wife marrying into a family thereby acquires her right to a share of the land, (relinquishing her portion in her old home if any). There is no distinction of sex in any provision of the code. In fact there is an explicit provision against any sex distinction in the apportioning out of land.

It can be imagined what a powerful lever all this must. be against the old patriarchal tradition of the peasant, even though it may remain as yet more or less unobserved. The Proletarian, State, which enforces the principle of the Social Ownership of land, standing on the side of the youth, and furnishing financial credit so sorely needed by the peasant, will sooner or later impose its whole morality upon the life of the Russian peasantry, “the ruling ideas of any age” said Marx, “are only the ideas of the ruling class”. And the Soviet rouble, although the emblem, “workers of the world unite”, owing to the exigencies of trade agreements, no longer appears upon it, must inevitably be a powerful factor in spreading the Soviet ideal. The great ferment of change among the peasantry has undoubtedly begun.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr was a major contributor to the Communist press in the U.S. and is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1923/v03n48[28]-jul-05-Inprecor-loc.pdf