A fantastic look at the changed world of workers’ intellectual life in Soviet Russia written for U.S. audience by Moissaye Olgin and first published in the Forward.

‘How Workers Study in the Russian Universities’ by Moissaye Olgin from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 4 No. 21. May 21, 1921.

The working class has come into power in Russia, and is naturally preparing its own intellectual development. Individual workers studied even under the old regime. Otherwise a militant working class would have been impossible. It is thirty years since the best Russian workers began to study. They studied in forbidden places and in prisons and in Siberia. They neglected no means to obtain ideas. Now the enlightened workers have become the doers, the leaders, the revolutionary vanguard of the working class. Now they occupy the highest places in the Soviets, in the Communist Party, in the management of factories, in the trade unions. They are the backbone of the proletarian government. It is their government, their regime, and if things go wrong they have themselves to blame.

If you talk with such a worker you will not see any difference at first between him and a bourgeois intellectual. He has for so long read, listened, spoken, mingled with party workers, that he has acquired the style and manners of an educated man. But sometimes an error in his speech, an ungrammatical expression, betrays the fact that he has not studied at school. Thus, for example, he sometimes says “collidor” for corridor”, “takhtical reasons” for “tactical reasons”, or he uses a foreign word in an incorrect way.

But this is not the real difference. It has often happened in a long talk with a Russian worker that I have not been able to decide where he had received his education: in a university or a factory or in revolutionary work.

Worker and Bourgeois Intellectuals

Where, then does the proletarian intellectual differ from the son of a merchant or a manufacturer? Chiefly in knowing thoroughly the life and thoughts and feelings of the laboring masses. It may be that he himself sits in an office or in an executive committee; he may not have worked in a factory for years, but a worker he remains nevertheless: he feels the spirit of labor, he can speak with the workers as one of them, he can see clearly what oppresses them. Not one of the bourgeois intellectuals, no matter how much he has “observed” the life of the worker, will have such an intimate knowledge of the proletarian world one who has himself been a worker from childhood.

Besides, the worker-intellectual has other needs than the professional intellectuals: the latter need refinement and luxury, the most beautiful and the best in the capitalist world; if they lack these they will be unhappy, they will be unable to work. The worker-intellectual, on the other hand, can content himself with less; he can adapt himself more readily to difficult conditions; he has greater physical and moral strength. This can be illustrated by the difference in their peculations; an intellectual who steals while occupying the position of factory manager, will steal enough for a piano; an intellectual who has formerly been a worker will in the same position steal enough for an extra pair of boots; of pianos and automobiles he has never dreamed.

A third important difference is that “intellectual” activity is not for the worker his only means of livelihood: if fortune changes he takes off his coat, rolls up his sleeves and sets to work, laughing at all his troubles; his hands will always furnish him with bread. For the intellectual, on the other hand, this activity is his livelihood. If he loses it he is a fish out of water. That is why he thinks that without him the world will perish. In general he is more bound by traditions and theories, he has less spirit and less strength than the worker-intellectual.

The Worker Intellectual and the Masses

But the greatest difference is that the professional intellectual is better off in a capitalistic order and the worker under a proletarian order. If tomorrow another Kolchak comes into power in Russia— all these bourgeois intellectuals who now speak of freedom and democracy will become the leaders and the rulers in political as well as in economic life (as was the case under Nicholas}. They will be at the head of the country. Naturally, the bourgeois cannot be true friends of the Soviet government—a few idealists excepted. The workers intellectual, however, knows that if the Soviet government falls, his power falls with it, bis pride, his reign. And so he is devoted body and soul to the present regime. For him it is not a theoretical question of a better or worse form of political state—for him, for his class, it is a question of slavery or dominion. Today, under the Soviets, Sergei the smith, is a commissar, a commander, the administrator of a province, a judge, a diplomat. Tomorrow, if there should be a capitalistic system, this same Sergei would be dirt under the feet of the employers: if they wish they dismiss him; if they wish they put him on the black list and he perishes without work.

Therefore the working masses have more faith in a proletarian intellectual, even though he is doing no physical work, and is living the same life as an intellectual of the bourgeoisie. They feel that Sovietism is for him a serious thing. They will perhaps be unable to explain why they prefer him: he is not as good a speaker or so capable as the bourgeois book-man. Yet they know instinctively that he may be trusted.

How the Worker Intellectual Is Trained

But more proletarian intellectuals are wanted. In the time of Nicholas very few workers could educate themselves. Only after the November revolution did Russia begin to create a broad intellectual class of workers and peasants. Now the whole country is one great school of proletarian education.

Disregarding the popular schools and the secondary schools for children and the various courses for adults in evening schools, clubs, trade unions, factories we have three kinds of fundamental educational institutions for workers and peasants: 1. workers’ faculties, 2. military schools, 3. party schools. In all these institutions the teaching is scientific, not popular, and all three are great factories of proletarian intellectuals.

The Workers’ Faculties

The workers’ faculties would in America be called perhaps preparatory schools, because their aim is to prepare workers and peasants for the universities. There is a difference, however, be tween the preparatory school and a workers’ faculty. The faculty so conducts the studies that its students must from the first day accustom themselves to a scientific method of investigation.

This is their method: they bring together several hundred young men and women workers and peasants—from 16 to 20 or 25 years of age—they give them several professors from the university or the polytechnicum, they give them dwellings and rations—and they study. The students are picked; a recommendation from a factory, a union or a local Soviet is required for admission. Most of the students are sent by the various institutions and are supported at their expense: they are workers or peasants who have already distinguished themselves in community work, and proved their ability and spirit. In the workers’ faculties the task of the students is to become acquainted as quickly as possible with the scientific method in order to be able to carry on scientific investigation.

The workers’ faculty, then, is more a gymnasium (a secondary educational institution (eight years) between elementary schools and the university) and less a university. It is different from a gymnasium in that the learning is very serious and scientific. It differs from a university in that it leads the students only through the first stages of scientific investigation, but in the university spirit. The future mathematician learns arithmetic, algebra and geometry, on a purely scientific basis. The future economist studies the history of society, the elements of political economy and so on—but not as popular studies. The time is divided into trimesters—terms of three months each. The entire course must be completed in six trimesters—that is, in twenty months, (including vacations). When the course is finished, our worker or peasant becomes a full-fledged student of a regular university or technological institute.

I have seen the student, I have visited his classes. He is a new kind of student, another sort of intellectual. In appearance he is a “tramp”—a Vanka or Vaska or Styepka, who heats the oven in the factory or works the soil in the fields. But what a hunger this Vanka has for learning! With what wild eagerness he attacks the courses. Laziness is unknown to him, and complaints of hunger. He works. He studies from morning till late at night. He and his fellows overcome every difficulty—within and without. Sometimes the class rooms are not heated. Sometimes there is no writing paper. Sometimes the electricity fails and fagots must be lighted, if there is no kerosene. Sometimes hunger gnaws at the stomach. But the work goes on. With iron will and patience the young students go on developing their minds, training their spirit of investigation. When they enter the university then only will they try their wings.

The distinguishing characteristic of the workers’ faculties is that they give only the most essential, but they give it scientifically. The student is saved from many foolish and childish “predmet” (subjects) which would be stuffed into him in the gymnasium; what he does learn is serious and fundamental. A worker who can read, write and figure, and has a good head, if he studies through the six semesters, can be prepared for the university—perhaps much better than a former “gymnasts.”

Workers’ faculties have grown up over the whole length and breadth of Russia. They function in all the provincial capitals and in many county capitals. They are being opened even where there is no university. The expectation is that after the students finish they will be sent to the nearest university town, or that meanwhile a university will grow up about the workers’ faculty. In fact the workers’ faculty is becoming in many places the cornerstone for a complete university. It accommodates several hundred students, Throughout Russia there are tens of thousands of such students. When they have completed their courses they will become “specialists” (in various scientific branches). It is hoped that they will be more loyal than the present day “specialists” who have been left as a heritage of the bourgeois regime.

The workers’ faculties have been organized only within the last two years.

The Military School

2. The military school (military courses) is a school for Red officers. Just as the factory must have an engineer, so must the regiment have a commander: both are “specialists”. And as the factory made use of the former engineer, who served the capitalist regime, so the Red army made use of the former commander, who served the Tsar. But the former commander was less trustworthy than the former factory manager, and the Soviet republic has begun to create its own commanders from among the young workers and peasants. The idea is simply that there is nothing a young worker or peasant cannot learn to do, if only there be a teacher. Usually he learns more rapidly than a son of the bourgeoisie and makes better use of his knowledge in the interests of the new order.

It is remarkable with what rapidity the system of military courses has developed in Russia. In January 1921, the number of those taking courses was not less than one hundred thousand. About the courses in general I shall have more occasion to speak later. Here I will only remark that although the military sciences are taught there, a general education is also given, and in effect they are great factories of intellectual workers. Now that the war has ended, they are preparing to improve the courses and give the students a better education. I have seen thousands of students who have at least appeared more intelligent than the former Yunkers (military cadets), the children of princes.

The Party School

3. The party-school develops Communist social workers. The Communist party, as we know, is the government machine of Russia. The machine must have men. The men must have special training in all branches of management. The aim of these schools is to provide this training. They are divided into three classes, lower, middle and higher, and are under the local committees or the central committee. The lower school gives the most essential elementary ideas of society in general, and of Russia in particular. The middle school develops and adds to this knowledge. The higher school is a Communist university. All the schools are concerned with practical social work. The students engage in this work almost from the beginning.

The courses in the schools are not merely propaganda. They are not abstract. They have to do with practical daily questions. A social worker must now know everything, must be able to answer all questions. It is not as once, when an official used to come with an order: do so and so and ask no questions. Now questions are asked. And if you are a government official and cannot give a clear answer, you are good for nothing. A food commissar who goes about the country collecting grain from the peasants must be familiar with all food questions and especially know Russian conditions. A worker in a railroad union must know the union movement and everything that pertains to transport. The manager of a factory must a specialist in economic questions. If he lacks this knowledge he enters the party school. The number of such schools is very large. There is not a single county capital without one. The course lasts from three to six months, seldom longer. But the studying is done with a will. In Russia now everything is done in haste: there is no time to lose. Knowledge is seized, like hot cakes. There need be only a little foundation, the rest will be built up by practice and reading.

The Sverdlov University

The most able, the most educated young workers are sent to the Communist University in Moscow, named after Sverdlov. Concerning this university also there will be occasion to speak later. Here I will only remark that in this university is found the pick of the Communist youth. The’ courses formerly lasted three months, then six; now, since January 1921, a course of eight months is being given: five and a half months of theoretical work and three or four months of practical work in various commissariats. The number of students is above 1200.

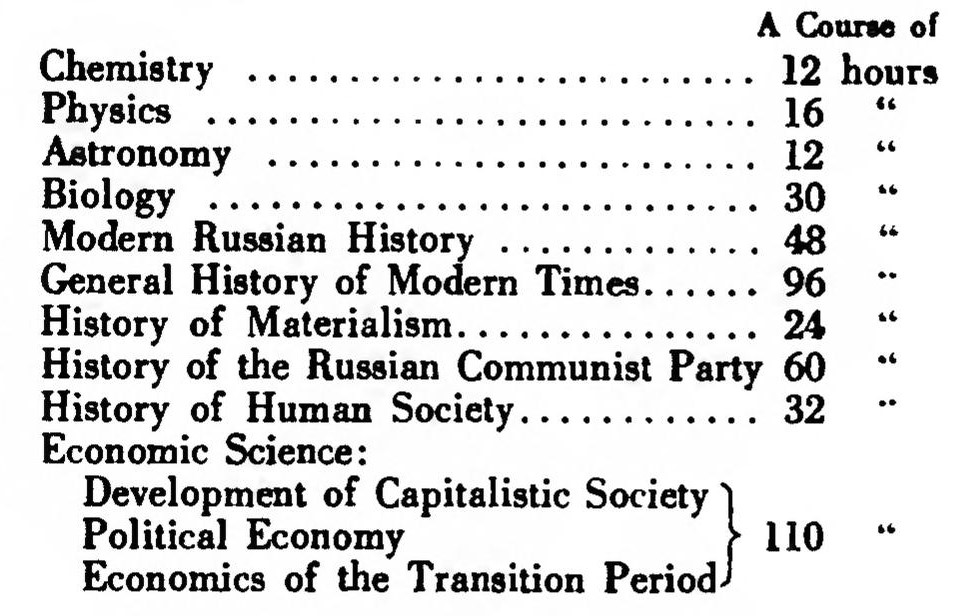

Here is a table of the subjects which are now studied there:

In addition there is a great deal of work in groups, seminars, practice in group reading, public speaking, etc.

Altogether: a course of 18 weeks, 36 hours a week. After the course is completed the students are assigned to various commissariats, each according to his choice, to see the machinery of government in practice. Later they return to the institutions which have sent them, and they themselves become government workers.

The New Intellectual

Thus a new intellectual is now being produced in Russia. He is not yet ripe. He is half-baked. He is not polished. But he has a terrible thirst for learning. He has the divine audacity that stops at nothing. And he is young! He knows no fear. He does not weigh everything. He is not tortured by doubts. If I cannot today—I will tomorrow. If I have made mistakes I am nevertheless richer in experience, and next time I will do better. And if it is hard meanwhile—well, I will suffer. And yet life is interesting—and long live the world!

Such is the spirit of these intellectuals. For, they are on the whole different from the bourgeois intellectuals. They are strong. They have blood in their veins, and muscles on their bones. If it is necessary—they will do physical work too. If they must—they will sleep without a pillow and eat next to nothing. In Nizhni-Novgorod I once spent the night at the quarters of the executive committee and in the same room a committee worker was sleeping on the floor near the stove, with a piece of wood for a pillow, and a thin coat serving for both a mattress and a quilt. In the morning the fellow turned out to be a commissar—with a hundred thousand soldiers under him.

He has no traditions—the new intellectual. He has not the thousand prejudices which for the bourgeois intellectuals are a sacred heritage. He dares everything. Critics call this experimenting. So-be it. One thing is clear: the new intellectual is not bored. He lives with all his senses. He lives years in one day. And how thankful he is to the old intellectuals when they come and share with him their accumulated knowledge. Professor Pokrovsky, the historian, they carry about on their shoulders. Why? Because he is one of them, because he gives his knowledge to the working class. But such as Pokrovsky are rare, they can be — counted on one’s fingers. The rest—the great mass of the learned and the specialists—grumble and complain. That pleases them more. And they still wonder that they are not respected.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: (large file): https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v4-5-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201921.pdf