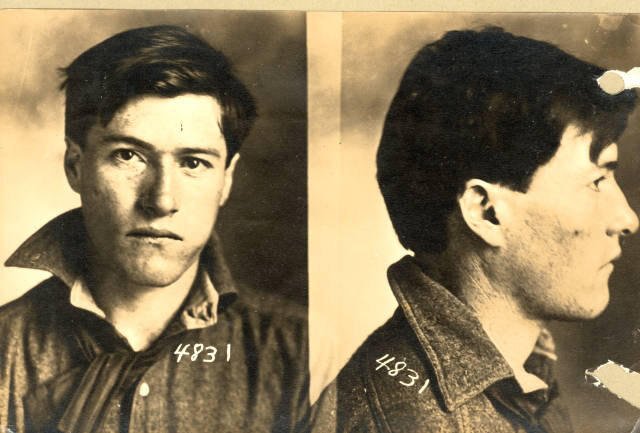

Imprisoned survivor of the Everett Massacre, comrade Harvey Hubler refuses to break ranks with his fellow workers.

‘A Soldier of the Class War’ by Stumpy from Solidarity. Vol. 8 No. 385. May 26, 1917.

An Interesting Character Study of One of the Everett Survivors

Could the rebels of the East and the West know each other as they and understand the heroic and manly fight that the others are putting up for industrial solidarity it would form a bond of fellow workership that would be unbreakable. There are men and women in the East as staunch as any in the West, but I would like to tell those in the East of a western man who can not be beaten anywhere for devotion to the principles of the one union. The one I have in mind now was no more true than any other of the 73 who stood by their principles all the time, but he was called upon to show his colors in a more dramatic manner than most of the others were.

Harvey Hubler was twenty-one years of age when he went on the ill-fated trip of the Verona on Nov. 5, 1916, to Everett. He was born in Illinois, but has lived most of his life in Los Angeles. He is six feet tall, weighs 165 pounds, has black hair, and his brown eyes have the look of one who has had the utmost confidence in humanity, but has awakened with a pained surprise to find that all men are not trustworthy.

During February Veitch and McLaren wanted someone in the Everett jail to substantiate the “confession” of Auspos, but they knew better than to try the game themselves, as they were known too well to the men inside. The game they played was to have a “lawyer” of Los Angeles go to Hubler’s relatives with a story of how poor Harvey was in bad company and if they would just trust the case to him he would have the dear boy out of jail in short order. And to help him in his game he had Harvey’s father, mother and sisters write letters to Harvey telling him to entrust his case to the lawyer and all would be well.

When the “lawyer” went to the Everett jail there were none of the men there who were receiving any visitors who were unknown to them unless the jail committee from their own tank was allowed to be present. When Hubler was called out he took the jail committee with him, but this did not suit the “lawyer.” He only stated that he wanted to talk privately with Harvey and said that he had letters from his folks, and that he was there at their request to represent the boy. He wanted Hubler to read the letters but Hubler refused to do so and told the “lawyer” to read them aloud so the jail committee could hear them. This the “lawyer” refused to do and Hubler was taken back to the tank with the committee. Later in the day, Hubler and another of the prisoners were in the corridor of the jail hanging up their blankets to air when one of the jailors shut and locked the door, and four or five jailors took Hubler and the other man upstairs by force to the women’s detention ward. The other prisoner was at once taken back to the tank, and the “lawyer” and two jailors began working on Hubler to break him down. The “lawyer” did nearly all the talking. He again showed Hubler the letters from his folks and wanted him to read them but Hubler again refused, so the “lawyer” read them for him. When the letters were read the “lawyer” said that he could get Hubler out of the jail before night, and have him walking the streets a free man before sundown “if you will only trust your case to me.”

Hubler’s only reply was that the I.W.W. had attorneys to defend him, and to make a demand that he be taken back to the tank. When it was seen that Hubler would not talk or listen to the “lawyer” he was returned to the tank and there were no more attempts to break down any of the men there.

The prosecution had counted on Hubler’s love for his mother and his youth and apparent lack of knowledge of the world to get him into a condition where he could be led to desert his fellow workers to gain his own freedom. But though the boy’s lips quivered and his eyes grew moist when his mother’s letter was read to him, he kept his head and refused to treat with the “lawyer” who was there to get him out “before sundown.” He did not allow his affection for his mother and father to blind him to the fact that the jailors could have given him the letters to read in the tank, or that if they had his welfare at heart they would not need to force him to listen to a stranger when they were denying him the privilege of a private conversation with the lawyers engaged by the I.W.W. Auspos was one of the first turned loose after Tracy was acquitted. As this is written Harvey Hubler is being rewarded by Snohomish County by being one of the eight who are still held with perhaps some hope that there can be a conviction made on some charge yet. Harvey Hubler himself, when questioned about the affairs says, “Aw, that was nothing much,” but millions have worshiped at the serine of men of less heroic fiber than his. And Harvey Hubler is but one among seventy-three who are just as staunch soldiers of the social revolution.

STUMPY

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1917/v8-w385-may-26-1917-solidarity.pdf