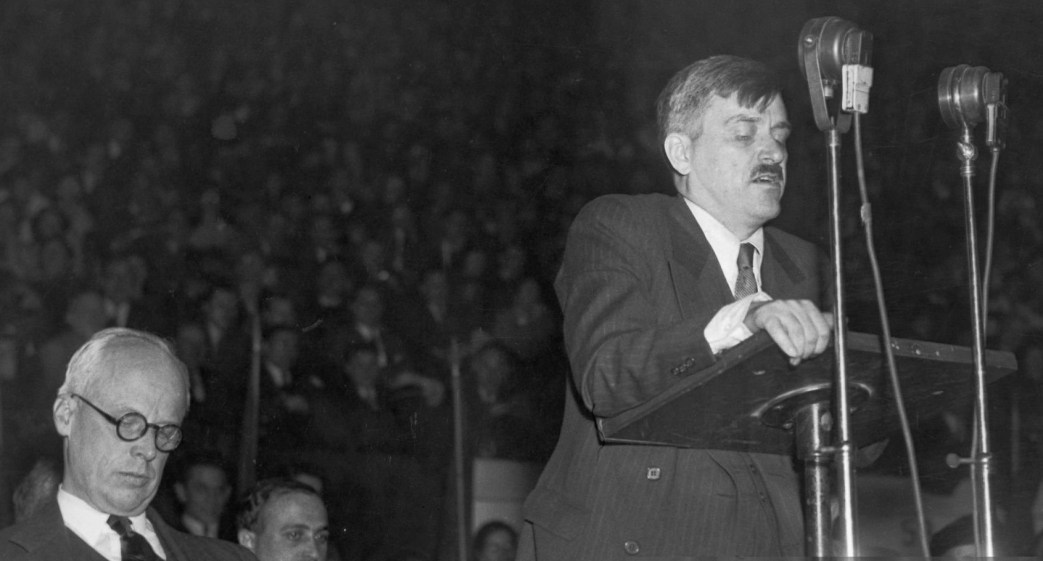

A useful summation by then top Party leader Clarence Hathaway of the Communists’ stated reasons, aims, and practice of the ‘Popular Front’ as it transitioned to the late-1930s ‘Democratic Front’ phase, with both terms, and their differences, defined below. Hathaway would later be accused of having a long relationship with the Federal Bureau of Investigation and was quietly expelled for ‘drunkenness’ in 1940.

‘Building the Democratic Front’ by Clarence A. Hathaway from The Communist. Vol. 17 No. 5. May, 1938.

THE realization of a broad democratic front of all labor and progressive forces is the heart of the draft resolutions which the Central Committee submits to the Party member ship in opening the pre-convention discussion. The main resolution, “The Offensive of Reaction and the Building of the Democratic Front” (see The Communist for April), states:

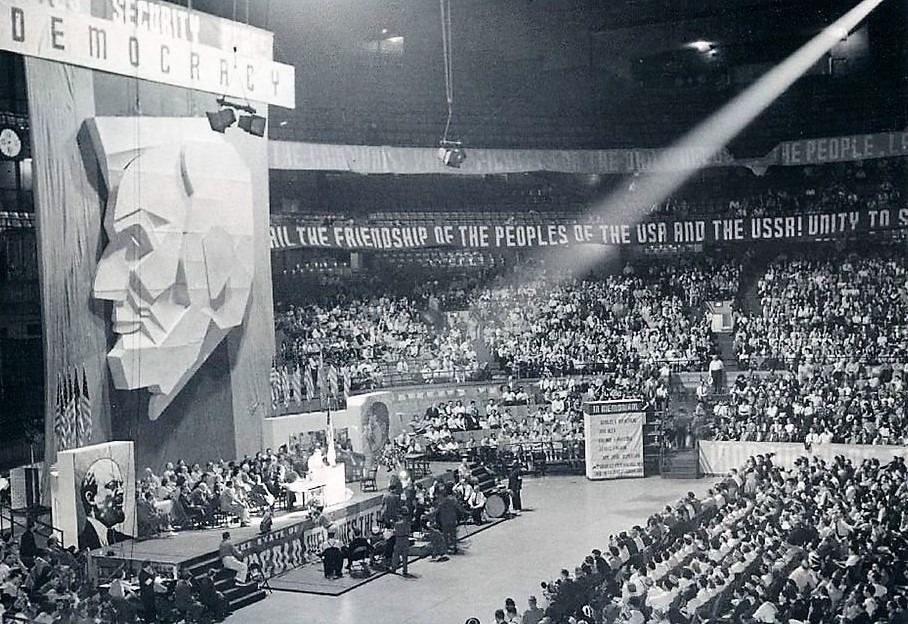

“The chief task before the working class, and therefore, above all, before the Communists, is to defeat the offensive of finance capital and block the road to fascism in the conditions of the developing economic crisis. To achieve this aim, it is necessary to unify and consolidate all labor and progressive forces into one single democratic front. This demands the strengthening of all economic and political organizations of labor; the building of the C.I.O., the organization of joint action between the unions of the A.F. of L. and C.I.O., as well as the Railroad Brotherhoods, especially in the forthcoming elections, leading toward the achievement of full trade union unity, labor’s initiative in gathering the farmers, the middle classes and all progressives into the general democratic front; and to defeat all efforts to split this front by reactionary Republicans operating behind a progressive shield.”

The question may arise in the minds of some of our comrades, “Just what is this ‘democratic front,’ and what is its relation to the People’s Front, to the Farmer-Labor Party?” They may ask further, “Does this conception of a broad democratic front constitute a revision of the line of our Party?”

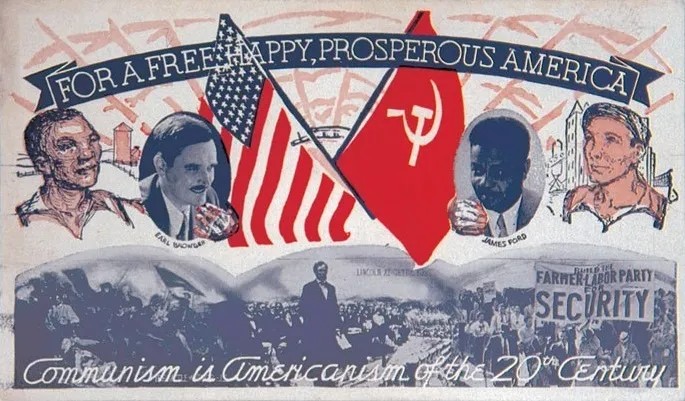

To answer the last question first, it does not constitute a revision of our line. Our goal still remains the building of a nationwide Farmer-Labor Party, as an American expression of the People’s Front. Our proposal now—today—for the creation of a broad democratic front is based on a realistic appraisal of the present stage in the political regrouping of class forces in the country, and is designed to further and speed up that regrouping. It is a policy for this immediate period and, if energetically and successfully carried through this year in connection with the State and Congressional elections, can contribute to the early realization of a People’s Front; it can further the movement for a Farmer-Labor Party. In short, the effort to achieve a democratic front is an effort to advance a step closer to the People’s Front.

Now, just what is it? First, as in the case of a People’s Front, a democratic front would unite in one progressive political camp the main body of the people, the workers, farmers, Negroes, small business people and professionals. It differs from the People’s Front in that it recognizes that at this time it is not yet possible to organize this broad mass movement in a new party, let us say, like the Minnesota Farmer Labor Party, nor is it possible always to unite this movement through a formal set of political alliances between the different progressive political groupings, or on a commonly worked out political platform. The democratic front presupposes a more loosely knit coalition of what are in the main progressive forces, with a program generally progressive, but less clearly defined. To illustrate this difference one can contrast Minnesota and New York City.

In Minnesota the Farmer-Labor Party closely approximates an American type of People’s Front. There, the workers, farmers, professionals and small business people meet together in convention, with the delegates coming directly from the trade unions, local political organizations, cooperatives, etc. They draft their platform, select their candidates, choose their party officers and plan their campaign in a united, disciplined way. Communists participate freely, with “Redbaiting” squelched by the party leadership. Though there also they have the problem of an election alliance with progressive Democrats, this is done on Farmer-Labor terms and in an open, official manner. This is a practical example of the People’s Front.

In New York City, in the anti-Tammany coalition of the last campaign, we had an example of the democratic front, reflecting a less mature development than in Minnesota. Here we had the American Labor Party as the core of the whole anti-Tammany drive, a party that had emerged during the Presidential campaign, that had grown rapidly, numerically, and in prestige before the city elections, but which was not strong enough to uproot the entrenched Tammany machine alone. Then followed a series of “deals,” bargains and compromises with Republicans who were made to accept a ticket hardly to the liking of their Tory wing, with progressive Democrats, with the Fusionists and with “civic reform” groups. Though the American Labor Party had a platform which Mayor LaGuardia accepted, the coalition forces as a whole had no commonly agreed upon platform. They had one plank on which they agreed: Defeat Tammany!

In this very loose coalition of anti-Tammany forces New York experiences teach us:

1. The possibility of bringing together the broadest mass of the people in a winning coalition against reaction, furthering the break-up of old political alignments;

2. The necessity for the independent organization of labor on the political field to initiate and force through such a coalition;

3. Labor’s ability, when it is so organized, to establish its own leading role within the whole movement and among its elected representatives, thereby opening the way for further advance on the road toward a People’s Front. In short, New York is not Minnesota, but it leads toward Minnesota. And interestingly enough, the early developments in Minnesota in the formative period of the Farmer-Labor Party are singularly similar to those of this period in New York.

From these examples the character of the democratic front should be clear, and also the role that it plays in furthering the break-up of the old political parties and in advancing the People’s Front.

This idea of the democratic front, though given this name only at the Party Builders Congress and Plenum in February, and then only to avoid confusion as to the character of the People’s Front, is not something “new,” suddenly sprung on the Party. The idea of support for such a loose coalition of the progressive forces with its candidates sometimes running on the Democratic ticket, sometimes on the Republican ticket, and at other times independent, is inherent in the work of our Party for the advance of the People’s Front over the past several years.

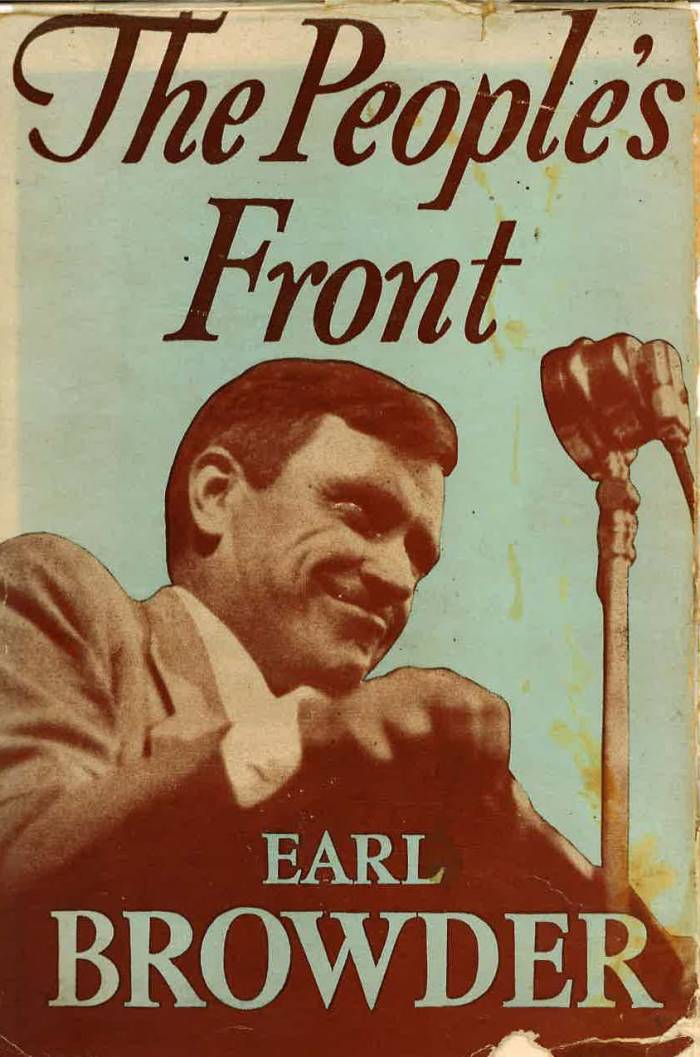

In fact, Comrade Earl Browder has formulated this as our basic tactical approach to the struggle for the People’s Front in numerous speeches and Plenum reports. Let me cite some examples. As far back as the December, 1936, Plenum, Comrade Browder stated:

“We must soberly estimate, however, the moods and trends among the broad progressive ranks. We must find the way to unite the movements already outside of and independent of the Democratic Party and progressive Republicans together with those that are still maturing within the old parties, and not yet ready for full independence. This means that we must conceive of the People’s Front on a broader scale than merely the existing Farmer-Labor Party organizations. We must conceive of it on a scale that will unite the forces in the Farmer-Labor Party and other progressives together with those forces crystallized in some form or other but not yet independent of the old parties.”

At the June, 1937, Plenum, Comrade Browder dealt exhaustively with the problems that had arisen in our efforts to build a People’s Front; bringing out “an apparent contradiction between the clearly established growth of People’s Front sentiment in the United States, and the slowing up of the organizational realization of a national Farmer-Labor Party.” In that speech he established the following main points which are the basis for the democratic front tactic:

1. That the foundations of the old two-party system, “based upon regional interests of the main sections of the bourgeoisie, accentuated by the federal structure based on forty-eight sovereign states and the incomplete national unification of the country” were shattered, and that, “In their place there emerge the clear outlines of two new parties…representing something new—a political alignment dominated, not by regional differences among the bourgeoisie, but by class stratification among the masses of the population.” He added that there was no longer a fixed party structure in the country, that everything is in flux, that everything is changing.

2. That in this shake-up the rise of sentiment for the People’s Front was tremendous: “It is precisely because of the exceptional breadth and speed of the rise of the Farmer-Labor movement,” he stressed, “that there has occurred what seems like a pause in organizing the national Farmer-Labor Party.”

3. That this disparity was due to the desire of the masses for immediate political victories, which experience has taught them in a number of instances could be achieved through the Democratic Party and in some cases through the Republican Party, when labor and progressives organized themselves independently for that job in bodies such as Labor’s Non-Partisan League, the Commonwealth Federation, etc. The fact that they could win, and that they now have victories to guard, stimulates their progressive and independent political activities, and at the same time causes them to hesitate in the building of a new party. Additional, purely American factors, such as the difficulty of getting a new party on the ballot in many states and the existence of the direct primary system in most states, are also obstacles to the speedy formation of a Farmer-Labor Party.

Comrade Browder summarized the Central Committee’s position:

“The Farmer-Labor Party, conceived as the American equivalent of the People’s Front of France, is taking shape and growing within the womb of the disintegrating two old parties. It will be born as a national party at the moment when it already replaces in the main one of the old traditional parties, contesting and possibly winning control of the federal government from the hour of its birth. What particular name the caprice of history may baptize it with is immaterial to us. This new party that is beginning to take shape before our eyes, involving a majority of the population, is what we Communists have in mind when we speak of a national Farmer-Labor Party, the American expression of the People’s Front.”

The tactic of the democratic front is designed to meet precisely this situation, where the Farmer-Labor movement is growing by leaps and bounds, but in widely varied forms, both within and without the old parties. It is designed to keep our Party in closest relationship with this whole broad people’s movement and with its spokesmen, in order that we may contribute most of its immediate unification in today’s fight against reaction, and aid it in breaking down the obstacles that stand in the way of the People’s Front, of a Farmer-Labor Party.

The fight for the democratic front, for the unity of workers, farmers and all progressives now in a loose form, I re-emphasize, is the correct tactical course to follow on our road to the People’s Front under American political and electoral conditions.

Here I do not wish to discuss programmatic issues which arise in connection with the democratic front tactic, but rather some of the practical organizational obstacles which will inevitably be encountered. Proposals for program and platform are adequately handled in two of the draft resolutions: “The Offensive of Reaction and the Building of the Democratic Front” and “The 1938 Elections.” For a further handling of these problems one can refer back to Comrade Browder’s speech at the November Enlarged Political Bureau meeting (The Communist for December), to the speeches at the Party Builders Congress (Bittelman, Stachel, Foster), etc.

The building of the democratic front is not going to be easy. The road will be strewn with every conceivable obstacle and pitfall. Our comrades will have to learn (and rapidly) to deal with new people, with new problems, and with most complex and most rapidly changing situations. Moreover, it is the particular task of our comrades to play the most active and constructive part in the solution of all problems, for the simple reason that as a rule the others will not or cannot. Their limited outlook or narrow party or group approach will usually cause them to play a largely negative role in tight situations. We have to be the unifying force and the cement that holds the democratic front together. We must make it a conscious, progressive, anti-fascist force able to rise above petty bickerings and self-seeking influences.

As an aid to our comrades, the following points should be stressed:

1. Broaden your contacts. Meet people. Establish connections, direct or indirect, with all progressive people influencing the political life of your neighborhood, community or state, with trade union leaders (A.F. of L., as well as C.I.O.), farm leaders, progressive civic leaders, progressives of both Democratic and Republican Parties, Negro leaders, etc.

2. Learn their political plans and try to influence them. Strive to bring all the progressive groups together, contributing all you can to ironing out conflicts and differences.

3. Don’t be passive, waiting for someone else to decide how the progressives are to enter the coming state and Congressional campaigns, with our Party and those whom we can influence merely following at the tail-end. Contribute your part, and through all channels, to the selection of the whole progressive slate, to the drafting of the platform, and to the conducting of the campaign.

4. Don’t be over-aggressive, acting as though we thought that we were the democratic front and able to dictate its policies. In a tactful, modest way we strive to participate in discussions and to put forth our proposals. We try to be correct and convincing on the basis of our general line, but we listen to other people. We try to incorporate their ideas, and to harmonize their views with ours and those of the others.

5. Base your proposals as to our role as a Party in the campaign on our actual strength and influence among the broad masses of the people. In New York the Communist Party can make proposals and play a role which would be quite impossible in a smaller place where our Party is weak or the progressive movement backward.

6. Don’t try to “capture” conferences, and don’t try to “capture” the offices. Play a role only in proportion to our mass influence and put forward such people as officers or candidates as are acceptable to the broader progressive forces. Remember, we bring forward our people “wherever such action will contribute to the unity and election success of the common front.” (Draft resolution on “The 1938 Elections.”)

7. Don’t imagine that you can escape a certain amount of “Red-baiting” in a democratic front, and don’t permit “Red-baiting” to become the central issue and, above all, a splitting issue. Our comrades must insist that the main issue is the unity of the progressive forces against the forces of reaction, fascism and war. We must meet the arguments of those “Redbaiters” who strive to split the democratic front in a quiet, restrained, convincing way, bearing in mind that it is the majority (which includes the vacillating liberal elements) that we have to convince of our right to participate and of the constructiveness of our participation. Again, in this connection, I refer the comrades to the excellent speeches of Comrade Browder on this question in his Boston declaration on force and violence (his reply to Roosevelt’s reference to advocates of dictatorships).

These points, and undoubtedly many more that could be added, are put forth in a positive way, but all of them are observations based on actual and sometimes costly errors made by our comrades in various districts (Minnesota, Boston, Seattle, Detroit, etc.). The democratic front requires the greatest flexibility, tact, and patience; and where these virtues are not acquired our comrades will have difficulties. “The organizational expressions and forms of the democratic front,” as the Election Resolution stresses (Point 4), “will have to be flexibly adjusted to the concrete situation in each state and Congressional district.” This means, above all, a careful weighing of all class forces, careful consideration of the traditions and experiences of the local movement, and a close relationship with all of the decisive progressives.

Finally, I want to stress the political unity of labor—A. F. of L., C.I.O., and Railroad Brotherhoods. Without such political unity the rallying of the other democratic forces will in the first place meet with serious difficulties. Moreover, it gives the reactionaries an opportunity throughout the campaign to exploit labor’s disunity for their own fascist purposes. The examples of Detroit, Seattle, and now Illinois, show the disastrous results of the A. F. of L. bureaucrats’ policies.

It is necessary, in a sense, to separate for the moment the question of trade union unity from that of trade union political unity. We must undertake to show the necessity now for such political unity of both A.F. of L. and C.I.O. workers and to local and state leaders in order to protect the interests of their own organizations.

In selecting slates of candidates we must urge consideration of both C.I.O. and A.F. of L. men or of men who are acceptable to both. Here the greatest concessions must be made in the interests of unity.

In considering organizational forms, where, because of the ruling of William Green, it is not possible to bring the overwhelming majority of the A.F. of L. people into Labor’s Non-Partisan League, other organizational forms should be sought out that conform to Green’s rulings, but that at the same time make cooperation possible between L.N.P.L. and that A.F. of L. political body in one democratic front. Every possible approach should be canvassed in our efforts to bring the trade unionists together. Most frequently the Railroad Brotherhood men can be the most effective negotiators for unity. In other cases one or another local progressive politician can fill the bill. But the job involves negotiations, “deals,” compromises, and outright bargains with the local and state A.F. of L. and C.I.O. leaders, and particularly with those of the A.F. of L. Broad agitation for unity within the trade union locals is, of course, essential, but to get unity the arousing of that mass sentiment must be followed by these behind-the-screen, back-door “negotiations.”

The situation in the country is favorable to the development of a democratic front. The people are undoubtedly alarmed by the sabotage of the big monopolies and their sharpening offensive against Roosevelt, the C.I.O., and all progressive measures. The people will see in our proposals a sound approach to their problems and needs, and to the struggle against the fascist, war-making forces.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v17n05-may-1938-The-Communist-OCR.pdf