This co-report of Gleb Krzhizhanovsky should be read with Rykov’s speech. The 15th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union held in late 1927 initiated the first Five Year Plan. While under the New Economic Policy, a multi-faceted debate on implementing industrialization had been going on in the Party. Very broadly speaking, two tendencies had developed on how to proceed. One, the so-called ‘genetic approach’ based the plan on existing trends within the largely peasant economy (Rykov, Bukharin, Bazarov, Kondratyev, and initially Stalin); another, the so-called ‘teleological approach’ sought to transform the existing economy through rapid industrialization (Kuibyshev, Strumilin Trotsky–expelled at this Congress) favored in this speech by Krzhizhanovsky, then head of the State Planning Committee and a key figure in the electrification program.

‘Directions for Drawing Up the Five Years’ Plan of National Economy’ by Gleb Krzhizhanovsky from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 8 No. 2. January 12, 1928.

The Results and Prospects of Economic Construction.

The question of a uniform plan of national economy was first brought forward in a comprehensive form at the IX. Party Congress in 1920.

That year brought a fundamental change in the life of our whole country. The war period of our revolution had just closed, and we were at the beginning of a peaceful “pause for breath”. At the same time we were in the midst of a tremendous economic decay. At that time our country was a country of poverty and misery in the strictest sense of the terms.

We began to build up a system of economy such as the world had never before witnessed, for the consolidation of the achievements of the October Revolution enabled our economy to be built up on an entirely new foundation, unknown to the capitalist world. There are some economists among us who maintain that a sharp distinction must be made between the period of the restoration of our economy and the period of rebuilding; they assert that during the first period of our development we followed a system inherited by us from the pre- war period, thereby facilitating our progress. They speak derisively of a systematic line of development during this period, for in their opinion the market itself has helped us since the introduction of the New Economic Policy; the market has corrected and instructed us, and the Plan has been of no importance.

In accordance with the resolutions passed at the IX. Party Congress in 1920, a general plan for the entire national economy was drawn up, and became generally known under the name of the “electrification plan”, the Plan of the State Electrification Commission. You know that Lenin hoped much from this programme; he was of the opinion that it was the basis of a second programme of the Party. This electrification plan provided for the erection of thirty electric works in the various provinces. It was assumed that in the course of ten to fifteen years we should have to expend about 1.2 milliard roubles for this purpose, and that it would be possible for us to raise our industry by 80 to 100 per cent. over the pre-war level during this same period. About 8 milliard roubles were to be expended for these purposes. It was assumed that 20 to 30 thousand kilometres of new railways would have to be laid down, and an expenditure of a further 8 milliard roubles was assumed for transport service. The plan assumed a total expenditure of about 17 milliard roubles for these three purposes.

It must be remembered that at that time we were already perfectly aware that the accumulation of resources in our industry itself would scarcely be able to meet the outlay required by the restoration of our decayed industries. and we intended to find the means for our vast work of restoration by exploiting the goods famine in Europe, that is, we intended to force export, and reckoned upon the aid of the post-revolutionary revival of peasant farming. We calculated at that time that with the help of a favourable trade balance we should be able to accumulate in the course of ten to fifteen years about 11 milliard roubles. This meant à deficit of six milliard roubles in the expenditure estimated for the above three purposes. Further, we calculated that the West would in all probability find it necessary to take up certain commercial relations with us. We reckoned upon an extensive concession programme; we hoped for credits, and expected that credit operations and concessions would enable us to cover this deficit.

The blow dealt us by the famine year of 1921 showed us the error of depending on these export surpluses, especially as we had thought to attain these with the aid of our agriculture. It was not until after 1921 that we became fully aware of the frightful extent of the decline of our economy, which permitted only a very slow increase in the production of agricultural commodities and showed the dependence of this production on a number of extremely complicated connections within the general economy of the Soviet Union, on the general public of the Soviet Union to the peasantry, etc.

Upon what is our Five Years’ Plan based, since it does not calculate on outside help to any considerable extent, and takes into account an export which is the weakest spot of our whole economy? Whatever errors we may have made in the Five Years’ Plans still the progress of our industry will be 80 to 100 per cent. by about 1931.

You will see that, even if we take the minimum assumed by our Five Years’ Plan, the general tasks laid down for our economic construction correspond exactly to the plan known during Lenin’s lifetime as the “Plan of Great Works”. We can only be ashamed that there are comrades among us who think these tasks too small.

But that is not all. You must remember that Comrade Lenin connected our whole economic development with the advance of an army of skilled workers, of specialists in every sphere of activity, without whose assistance all progress is impossible. How were matters in this respect at the beginning of the period of construction? Allow me to quote a document here. This dates from 1918, and was addressed to the Government by the All-Russian Union of Engineers, the Moscow science and technics organisations, the managing engineers, and the provincial department of the engineers union. It appeared after the six days of negotiations on the question of the nationalisation of industry. It is in itself a complete indictment.

This document placed on record that the power which took over the whole of our economic development in October failed in its task, that the Soviets did not follow the instructions of the higher Government authorities, that the People’s Supreme Economic Council had no definite programmes, that the whole project of the nationalisation of industry was built upon a treacherous foundation. undermining the spirit of enterprise and excluding the possibility of an inflow of foreign capital, etc.

This declaration closes with the following words: The nationalisation of industry, when not founded on any real basis, and when hampering the influx of necessary capital and raw materials and hindering technical restoration, is bound to worsen the disastrous position of industry still further, and to retard the rapid restoration imperative for the future of Russia. For this reason we declare ourselves, in the given circumstances, to be decidedly opposed to the nationalisation of industry, and we “lay the responsibility for this nationalisation on the representatives of the working class and the government which they have set up”.

And now another document: The appeal of the scientific and technical workers, issued on the initiative of the group of the “Society of scientific and technical workers for the pro- motion of socialist construction”. Here we read:

“The undersigned, taking part in the practical daily work of building up Socialism, in agreement, with the principles of the Soviet power, and in fullest sympathy with its aims, have arrived at the conviction that it is necessary at the present time to unite our scientific and technical forces on a definite ideological basis. In the present period of the development of the scientific and cultural life of the Soviet Union, such a unification is a necessary prerequisite for the successful advancement of socialist construction.”

You see that when we first took over economy, the most highly qualified groups of technical intelligentsia left us and were opposed to us. But this stage is now followed by another, in which this group returns to us.

We have proved sufficiently powerful not only to win over the technical intelligentsia to our side, but to bring about extremely important changes in the ideology of this group.

Nevertheless, the difficulties lying before us in our present first stage on the road to creating socialist economy, are still immense. It suffices to call attention to the three general tasks forming the decisive factors of our Five Years’ Plan.

What are these three tasks?

Firstly, it is our aim to carry out our industrialisation, to reorganise our whole, economy on the basis of electrification, and to conduct our whole economy according to plan, to the end that we attain a rate of economic development unknown to the capitalist world.

Secondly, we must pursue a determined course towards the socialisation of economy, proceed with this process of socialisation on lines ensuring the steady rise of the prosperity and cultural level of the working masses.

Thirdly, in view of the international situation, we must secure the military power and defence of our country and reinforce these by all the means at our disposal.

The difficulties which we have to overcome are enormous. The first necessity for overcoming them is a tremendous unity of will.

What is the Economic Plan, what is its actual essence? Its actual content is an endeavour to school us to a united economic will. Who can guarantee, in our country, the most rapid realisation of this united will? The Party alone, our decisive and organised centre, the firmest stronghold not only of our political but also of our economic fronts.

The Stages of Planned Work.

I should like to give you a more or less clear idea of the actual stages of our planned work. I should like you to understand clearly what demands you are really entitled to put on those who work out the plans, and what is the actual significance of the figures and comments with which we accompany our Five Years’ Plan at the present time.

Whenever we hear of attempts at planned economics in the capitalist countries, we must remember that although there have been critical moments, during wars for instance, in which the capitalist countries have been forced to resort to a systematical conduct of economic life in order to utilize all forces for war purposes, in reality it is still money which rules in these countries, and any Socialism based on the reign of this yellow metal will be yellow Socialism, a transitory period of. what might be named “yellow planned economics”. These plans, as they are set up in the capitalist world, collapse as soon as they encounter a stronger capitalist group. We, however, are dependent solely on ourselves, and if unity of will is our head trump, you may well imagine what a high degree of unanimity and agreement of will is required if we are to sign this bill of exchange for five years from motives of actual conviction, and not merely because we are obliged to.

What has been the actual course of our systematic construction? As early as 1920 a rough outline of the ground plan of our economy was drawn up. Then the struggle against economic decline began. Comrade Lenin advised us those comrades engaged on the elaboration of the plans. to set aside for the moment our general ground plan, and to tackle the most urgent questions of our economic life in this emergency. The State Planning Commission, organised in 1924, was at once engaged in a struggle against the crises in the food, fuel, and transport services. It took some time before we were gradually able to return from these questions to the actual lines being laid down for planned economy.

Let us take for instance State industry. At the first glance it would seem as if it must be possible to introduce a planned regime here with special rapidity. But in reality it was not until 1925 that we had a comprehensive plan for all industry, including the technics of production, the economic analysis, and the financial programme.

The year 1925 terminated a certain process of reorganisation in our economic structure. Building activity increased; and industry made more rapid progress. A period began in which it became necessary to embrace in one comprehensive plan not only the plans for the various branches of industry, but at the same time the whole of the plans for the most important departments of national economy. Since 1925/26 we have been working out control figures for national economy, furnishing the basis for the fulfilment of this task.

The first control figures of the State Planning Commission (1925/26) were compiled exclusively by the collaborators. of the State Planning Commission itself. The Government could not make use of these figures for working out a plan of economic operations.

In the following year (1926/27) a certain uniformity of system developed. For the first time the control figures contained general paragraphs referring to industrialisation, etc.

Finally, the control figures for the economic year 1927/28 are at last the result of extensive collective compilation. These figures have not been worked out solely by the staff in the State Planning Commission and the corresponding commissions in the separate Soviet republics. They are the final result of the research of many thousand economists all over our country. A number of Congresses were called. At these congresses the general methods of dealing with the material have been laid down, and it may be now stated that, as a result of the work already accomplished, we have now material at our disposal comprising the budget, the financial plan for our industry, and our import and export plans, as constituents of a uniform and consistent plan of economy. This combination has been given a form enabling the Government to make immediate use of the control figures for 1927/28, since these already offer firm bases on which to set up all operative economic plans.

It is obvious that the Five Years’ Perspective Plans must not constitute any limit beyond which we must not go. The extent of our development is so great that we cannot come to a standstill at this stage. When we remember that our reexamination of the prospects of the coming five years confronted us at once with a series of burning questions the question of unemployment, of the possibility of improving the prosperity of the working masses, and of the comparative strength of such huge branches of our economy as industry and agriculture we see clearly that we must pass as speedily as possible from the five years’ plan to the ten and fifteen years’ plan, that is, to the general plan. The imperative necessity of special activity in the interests of the transport service urges us especially in this direction.

I must accord a few words to the extension of railway transport. The freights carried already exceed the pre-war figures by about 13 per cent. You are probably not all aware of the extent to which the transport service is our heel of Achilles. Of special importance are: The extension of the Siberian lines and junctions, and the connections between the Donetz basin and our industrial centres.

If we do not greatly extend our railway network here, we hamper the development of our Siberian raw material basis, and deal a severe blow to the economic dynamics of the whole Soviet Union.

A second important factor is the transport of the Donetz coal, our most important fuel, exercising enormous influence on the whole economic life of our industrial centres, both in the central industrial districts and in Leningrad.

Lenin was of the opinion that one of the greatest dangers threatening us was the bureaucratisation of our planned economics. But this triply articulated system of our planned work prevents its bureaucratisation. We may put the matter as follows: Our most immutable instructions are given by the control figures, but with one reservation: Taking these control figures as a basis, we must none the less take into account economic fluctuations, constantly retest the correctness of the figures, and carefully observe the tendencies in our economy. More than this. Should the heads of the leading economic organisations be convinced that the control figures for the given year are wrong and misleading, then they may break through the confines of the planned instructions at their own risk, but must of course be prepared to substantiate the considerations which have led them to set aside the enactments. The control figures must be exactly coordinated with the Five Years’ Plan.

What figures are proposed by us for the Five Years’ Plan? The congress of economists collaborating in the plan came to the conclusion that it was impossible to advance only one set of figures for the Five Years’ Plan. A plan extending several years into the future is a distant aim. We must proceed like the artillery man. He examines his mark through his glass and then adjusts his aim to two possibilities. The first adjustment is a careful and cautions estimate, taking as the basis the minimum of economic possibilities, guaranteeing economy from unforeseen accidents. This is the preliminary adjustment. The second series of figures reckons with more favourable chances, which may in certain circumstances offer the possibility of reaching our goal more rapidly. If this optional estimate is not quite reached, it is no great misfortune. In spite of all difficulties, and in spite of our only breaking occasionally through the front of the elementary economic anarchy opposing us, we are advancing in the desired direction. The summing up of our economic possibilities under these two variations facilitates our economic manoeuvres.

The following must also be emphasised: If we find ourselves exposed to a serious danger of bureaucratisation in our planned work, it will be extremely useful to us to have the additional support, outside of the general outlines of the Plan, of independent economic organisations able to help us, the centre, in the solution of the most urgent economic problems. Special economic areas must be worked out, and the republics must become complexes of such economic areas.

The Experience and Lessons of the Restoration Period. Our Preliminary Line of Work.

The first and most important lesson to be drawn from the experience of the restoration period is the fact that the New Economic Policy has proved brilliantly successful. It suffices to follow the rate of our economic development, with the aid of the control figures, to see that the rate of development has not only exceeded our expectations, but at the same time the pre-war rate of development of our economy.

The second lesson to be drawn from our experience is the necessity of reinforcing our key positions. Comrade Stalin dealt with this when pointing out the facts and figures showing the extent of our achievements both in industry and in other spheres of national economy.

At the present time, as we approach the pre-war level of our economy, and in view of the social changes and transformations brought about by the October revolution, we come across many glaring discrepancies and inconsistencies in our economy.

The greatest capitalist trusts of today are able to produce as cheaply as they do by means of the methods of standardised mass production. These two methods, standardisation and mass production, form the foundation of the competitive struggle for the world’s markets. And since these vast trustified combines supply a gigantic output in absolute figures, we must exert our utmost efforts to ensure that the really systematic and technically economic unification of our nationalised industry increase in extent and power from year to year.

We read in the theses that we must seek the optional adjustment between heavy and light industry. You know that it is by no means easy to decide upon the most favourable ratio to be maintained. As an illustration I give one example: Let us take one industry, the beet-sugar industry, which is included under light industry. Think of the innumerable ramifications connecting this industry with agriculture and with the whole of agricultural technics, a mighty complex which must undergo a revolutionary reorganisation in the near future. There are beef sugar works everywhere, from the Polish frontier and Bessarabia to Tambov. In other districts of our country the prospects of the beet sugar industry are equally favourable. There are already about one million peasant farms in immediate contact with the beet sugar works, and this contact already contains within it the germs of far-reaching historical changes in the relations between industry and agriculture.

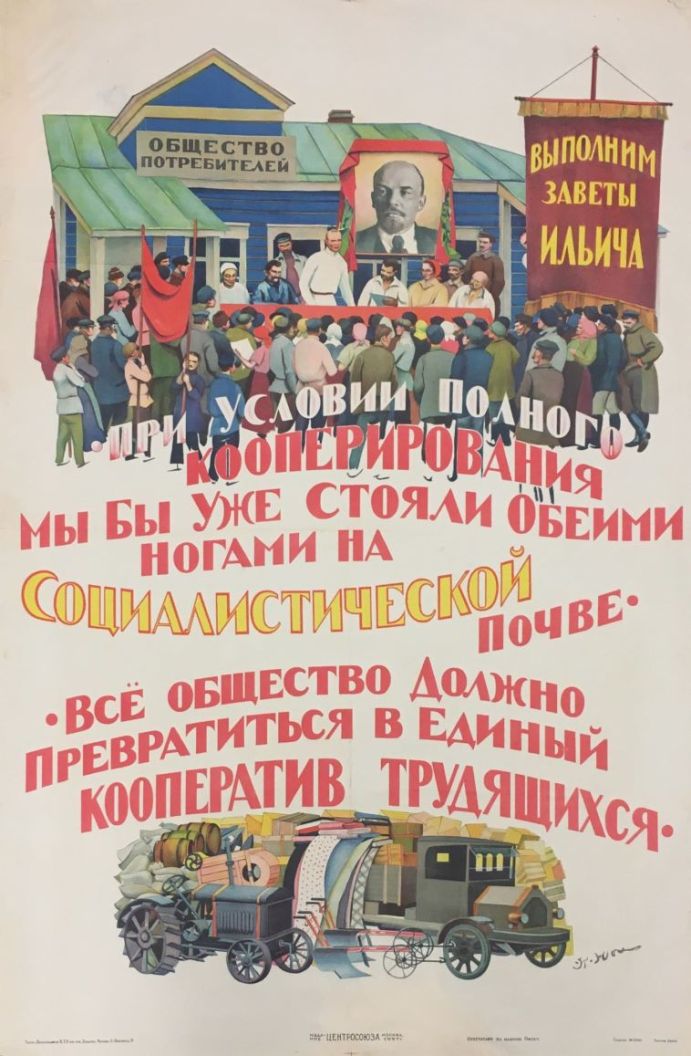

The mutual relations thus brought about have already enabled us to record many most desirable advances both with regard to the technical rationalisation of the beet sugar and its participation in the co-operative system.

In all these districts the beet sugar undertakings are the carriers of culture; they distribute pure seed, introduce fertilisers, build roads, maintain 450 agronomists, and carry on widespread agronomic propaganda.

If we examine the other branches of industry, we see that the task of the accurate annual determination of the proportions of our grants to heavy industry on the one hand and light industry on the other, is being carried out by means of extremely careful calculations, due consideration being given at the same time to the actual economic conditions obtaining at any time.

The New Economic Policy has justified itself, and the main lines of our great constructive work have proved right. The nationalisation of industry and of the land, the socialisation of home trade, the strong position of the foreign trade monopoly, are being fully justified by the general success of our pro duction, and by the systematic realisation of our plans for the future, which are advancing more and more decidedly in the same direction. There are still many relics of former anarchy in every branch of national economy. Our slogan is: Indefatigable effort for the suppression of this anarchy, unwearying organised and systematic pressure. This must not give rise to any buraucratisation, and the necessary elbow room must be left for economic manoeuvring, especially in such organs as the republics and the economic departments.

The centres will be able to feel complete operative confidence in the subordinate organs after the common goal has become clear to all, and a common will has crystallised, agreeing in substance with the whole of our economic work. Systematic planning is the decisive weapon for overcoming anarchy in every department of economy. The Plan cannot be worked out by any individual group of economists. The Plan of which we speak must be a real living Plan, and to be this it must be thought out collectively by the whole of the workers. The slogan which we issue for the coming five years, along the whole front of our economic work, our main and most important slogan, is: “Up with the Plan!” (Applause.)

It need not be said that we shall not escape partial defeats at times, both in our work and on the battlefield, even in the midst of our general success. But as Bolsheviki we shall not succumb to panic on account of such partial defeats.

The Main Features of the Five Years’ Plan.

I should like to draw your attention to the main features to be found in the Five Years’ Plan.

If we select two questions, accumulation and the investment of capital, and then compare the Plan with reality, we find that the difference between our projects in the Five Years’ Plan and the actual facts as stated in the reports is extremely small. Where a difference has been recorded, it has been attributable to natural caution.

We have found that we must not risk such expenditure at the cost of gigantic fresh investments from the means of the budget, but in connection with the successes gained in the rationalisation of industry.

One of the most important questions all these Plans is that of accumulation. Can we, on the lines of the Five Years’ Plan reckon on an accumulation of about 22.5 milliard roubles?

If we make a rough comparison of the resources of our present and our pre-war economy, we find the following quantities: in 1913 the profits and amortization (this is a far from comprehensive calculation referring to big industry, railways, trade, municipal property and banks based on share capital) in Tsarist Russia amounted to no less than 2385 million pre-war roubles or 4770 chervonetz roubles. This means a total of over 23.8 milliard roubles in five years, whilst according to the Five Years’ Plan of the State Planning Commission the total earnings and amortisation of the State section of our economics will amount in five years to only 15 milliard roubles, that is, a sum much below the pre-war level. This falling off is to be explained to a great extent by the contemplated reduction in prices and the increase in wages, measures not adopted in capitalist Russia.

It must, however, not be forgotten that even in the case of these modest standards of accumulation our possibilities of financing our national economy are much greater than in Tsarist Russia. In the first place, in pre-war Russia a not inconsiderable portion of the accumulation was devoted to the support of the bourgeoisie at home and to the payment of dividends and interest to foreign capital. In 1913, for instance, the actual increase of capital was only 1475 million pre-war roubles, although the sum total of profit was 2052 million. In the second place, we now possess the possibility of financing our economy not merely with the aid of the earnings of our State undertakings, but can draw upon the budget (6875 million roubles in the course of five years). Taken all together, our actual investments in national economy during this five years’ period considerably exceed the pre-war standard (21 milliards as compared with about 15.6 milliard chervonetz roubles in 1913 on the territory of the present Soviet Union).

We must count among the most important points of the draft which we here lay before you, besides the statements already known and published with respect to the work and growth of our socialised undertakings and to the price index figures, at the same time the question of our cultural development. If we want to increase the production of the industries coming within our systematic planning by 92 to 108 per cent. during the next five years, and if we take into consideration the great increase in building activity and in the investments in transport service, then the realisation of our plans is only possible on one condition. This condition is the really unanimous support of the great majority of the conscious masses of the workers. If we are to arouse the consciousness of the workers and train properly qualified helpers, we must exert our greatest efforts in cultural and social work.

The Five Years’ Plan provides for an expenditure of 13. milliard roubles for the work of cultural progress. This sum perhaps appears large to you. But if you examine the various items to be considered, you will be amazed at our backwardness. I need only refer to the most elementary questions of technical education. At the present time we have not quite one mechanic to each engineer in the technical middle schools, and at the close of the five years’ period, after having expended about 13 milliard roubles for social and cultural needs, we shall still have to each engineer not quite three specialised mechanics. You will see that there is a glaring discrepancy here.

This subject is extremely comprehensive. I cannot deal with it in detail, but lay down one main slogan: We cannot permit such a discrepancy to exist in our country between the expenditure for industrial advancement on the one hand and for social and cultural needs on the other; we cannot permit that only 0.025 per cent. of the means allotted to the one are left. for the other. (A voice: “Hear, hear!”). Our decisive slogan: must be: “We must place our social and cultural work on the same level as our industrialisation. (A voice: “Hear, hear!”).

Lenin’s Electrification Plan will be carried out.

We are very proud of the fact that whilst many of our economic plans are frequently interrupted, there is one plan which has been pursued steadily, and that is Lenin’s electrification plan. It need not be said that there too everything is not perfect. There are electric-works here and there which have not succeeded in becoming such centres of attraction for industry that they have rationalised this from top to bottom as anticipated by our electrification plan. But all these defects and shortcomings fade into insignificance when we remember that since 1921, the lowest level of our economic decline, we have been pushing forwards electrification with undiminished energy. We can now safely maintain that by 1921 this plan will not only be fulfilled, but exceeded.

A few fundamental data: In December 1921 the total capacity of the electric works on a provincial scale, including the combination stations, will amount to 2,141,000 kilowatts, without combination stations 1,800,000 kilowatts. The growth in comparison with 1921 thus amounts to over 1,500,000 kilowatts. The output of these electric stations will be 6320 to 6840 millions kilowatt hours by the year of the five years’ period; the total output 10 to 12 milliard kilowatt hours. Capital investments within the five years: Preliminary estimate 1400 million roubles, optional estimate 1600 million roubles.

In five years we shall supply our national economy approximately with as much electric energy as an industrially advanced country like Germany supplies.

When we observe the distribution of these electric works to be erected on the territory of the Soviet Union, we again receive the impression of well organised planning. You may see how a gigantic ring of strong current conduits gradually encloses the agricultural centres of our country. Within the next decade about 5 millions HP will be produced in this network. When we remember that about 70 million of the peasant population live within this centre, and that this gigantic electric ring will supply 5 million horse power, corresponding to an army of 100 million workers, we see that every peasant living in this agricultural centre will be able to afford 3 to 4 additional “mechanical slaves”. America is proud of the fact that it gives every independent farmer 30 such “mechanical slaves”. But an analysis of American economics shows that the want of systematic planning brings with it the loss of about one half of the energy of the country.

With the realisation of Lenin’s plans of electrification and cooperation we shall pass even America in the race.

The difficulties confronting us at the present time will be overcome if we really follow the path pointed out by Lenin. And we are following it. This is shown by the work of our Party Congress. Lenin’s prophecy will be fulfilled. The difficulties are great, but we shall overcome them. New forces are arising, mighty collective forces, and with their aid we shall sweep aside all these difficulties. (Prolonged applause.)

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n02-jan-12-1928-Inprecor-op.pdf