The U.S. has an incredibly rich labor tradition for us to draw from. Marxist economist and labor activist Jacob M. Budish participates in an extended forum in the pages of A.J. Muste’s Labor Age on ‘organizing the unorganized.’ This contribution on the question of union recognition through the experience of the Hatters, Cap and Millinery Workers. Born near Kiev in 1886 where he began his economic studies, Budish emigrated to the U.S. in 1912. Continuing his education at the University of Chicago and later Columbia, Budish became involved in the Yiddish-speaking workers’ movement, particularly the Cloth Hat, Cap and Millinery Workers International Union, for which he was editor of The Hedgear Worker between 1916 and 1930. In the 1920s and 30s he was was also involved in Brookwood Labor College and the Committee for Progressive Labor Action, as well as a founder of Ambijan, and organization in support the Biro-Bidjan, the former autonomous Jewish Soviet region, and author of a number of books on labor and the Soviet economy.

‘Recognition—By Whom? Success of Headgear Workers Experiment’ by J. M. Budish from Labor Age. Vol. 18 No. 5. May, 1929.

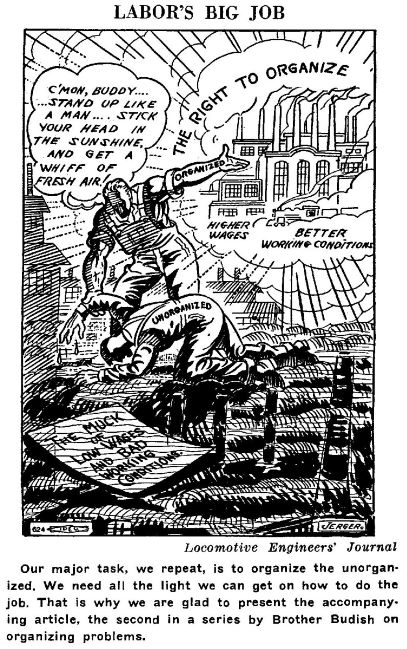

UNION recognition is acknowledged as the foundation stone of organized labor. But somehow this fundamental principle has been largely vitiated by putting the emphasis on Union recognition by the employer rather than by the workers. In its report to the last Convention of the American Federation of Labor the Executive Council declared; “Economic status comes through what we are accustomed to call ‘recognition of the Union.’ This means that the right of the workers to join the Union is recognized and the Union is accepted as the regular method through which matters of joint relations are determined.”

This attitude which considers that the workers cannot gain economic status or a firm position in industry unless their right to join the Union is recognized by the employer, puts its stamp on the policy of the Federation. In fact, it may be considered largely responsible for some of its most objectionable features. It explains why the Federation program for any organizing campaign provides for — “a message for the employer, particularly the employer of non-union labor and for the unorganized worker.” If recognition by the employer is so essential as to be indispensable, it is natural to direct your efforts first, to secure such recognition. For that purpose you carry your message first, and above all, to the employer and only then to the workers.

But if the message of the trade union movement is to be directed to the employer, particularly the nonunion employer, at the same time if not before it is directed to the workers, the message itself has to be formulated quite differently. It cannot very well be higher wages, shorter hours and workers’ control of industry. So the Union message is toned down. Says the Executive Council:

“The trade union rests its claim to recognition upon its capacity to do the things that are good for industry and for human beings.”

In its over-anxious chase after the employer’s recognition, the A.F. of L. is apparently unaware that it is losing in the process its identity and integrity. It does not base its claims any more on what the working people can accomplish through it for themselves, but on what it can do for industry and for human beings. Such an approach is not very much different from that of almost any industrial and social welfare agency. Trying to make its appeal to the employer, the Executive Council seemingly fails to notice that under this interpretation the trade union movement loses all character of its own and tends to degenerate into one whose purpose “is exactly the same as that of other intelligent progressive persons.” The labor movement thus becomes the expression and spokesman not of the working people but of that indefinite and undefinable group called intelligent and progressive people. (But to be sure, that does not include the “frothing” intellectuals and reformers.)

It is no exaggeration to say that this philosophy and policy practically precludes the initiation and the vigorous prosecution of any effective organizing campaign in the basic industries on the part of the A.F. of L. Whoever may be considered by the A.F. of L. as the “intelligent and progressive persons” they quite evidently have no share in the control of the basic industries. For they not only fail to recognize that their purpose is exactly the same as that of the “economic statesmen” of the A.F. of L., they do not even care to listen to the message and appeal of the trade unions. It is even impossible to secure an appointment with them in order to submit the plea for recognition. But as long as the entire campaign has as its starting point the securing of recognition by the employer, there is little else left to do except to wait for that blessed and happy moment when these employers will succumb to the education of the A.F. of L. and will become “progressive and intelligent.” On the other hand, it is hardly possible to expect that a message based on that abstract and general capacity of doing good for industry and human beings will have a greater appeal to the workers than “welfare capitalism” and “company unionism,” or other schemes of company made counterfeit.

A Mistaken Idea

Hence, the appalling impotence and helplessness of the A.F. of L. in the organizing of the basic industries. If Union recognition by the employers were really so essential as to make it indispensable as a preliminary condition for the success of any great organizing campaign, the situation would be almost hopeless. Fortunately, that is not the case. The entire conception is fundamentally erroneous. It is based on the mistaken substitution of the effect for the cause. Union recognition by the employers is not the cause of the economic status of the worker but its effect. It is only after the workers gain economic status in fact that recognition by the employer comes, and then it comes unavoidably and independently of the “intelligence and progressiveness” of the employer. A case from my own experience will illustrate this point.

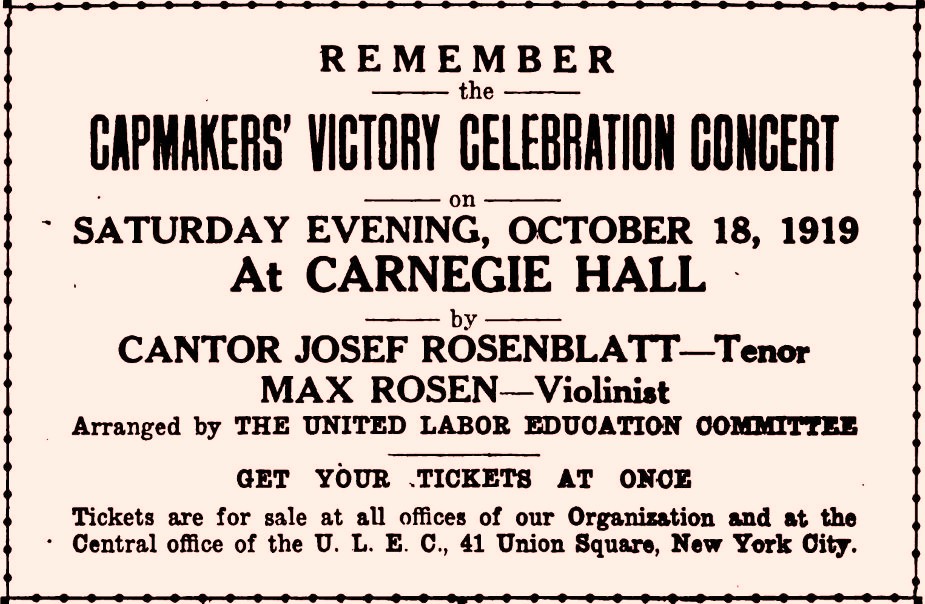

In 1919 the millinery workers union carried on a sixteen weeks’ strike in New York City. (The larger shops of ladies’ hats are concentrated in the so-called Uptown district, where about ten thousand workers, operators, cutters, jobbers and trimmers are employed.) The strike ended unsuccessfully in this Uptown districts. The workers were exhausted, discouraged and terrorized to the extent that they were afraid even to be seen on the street with a Union member, not to speak of a Union organizer. The situation seemed to be hopeless. The general attitude was that there would be no chance to again organize this major district of the millinery trade unless working conditions should deteriorate to such a low level that the Union would be able at some opportune moment to call another general strike.

Workers Recognition First

The 1919 strike involved an expense of over a quarter of a million dollars. Under the new conditions the Union would have to face much greater difficulties, and expenses. The Union treasury was totally exhausted. It seemed clear that another move of that kind would have to be delayed for an indefinite time. The prevailing attitude was that it would be useless to attempt to organize the workers shop by shop. There was not the slightest chance to gain Union recognition from the manufacturers in that way. There was no doubt the manufacturers were determined and prepared to fight any demand for Union recognition to the bitter end and to lend their entire support to any individual shop which might be tackled by the Union. It was further the general idea that it was impossible and, therefore, useless to try to organize the workers as long as there was no chance to secure for them Union recognition or improved conditions at an early date.

Needless to say, I could not share that pessimistic attitude. Union recognition by the employers is, to my point of view, of secondary importance. It is in any case merely an effect of the success achieved by the workers in solidifying their own ranks and in learning the principles and practice of collective and concerted action.

In 1 921, the writer submitted a plan for starting an organizing campaign, based on the slogan of Recognition by the Workers, caring naught for the moment whether we would be able to secure recognition by the employers or not. Under this plan it would be necessary to secure the adherence of the workers to the Union on the basis involving a deeper understanding of the principles of labor solidarity, implying a readiness to stick to the Union even when no immediate material gain was to be expected.

The plan provided for an organizing drive to be conducted with great discretion and circumspection. The early stages of the organizing campaign were to be based on a person to person canvass by visiting the workers at their homes’ and holding small meetings as far as possible outside of the district. For the first several months, it was not planned even to open an office in the district. There was no reason for the immediate opening of such a union office, for as already mentioned, the workers were so terrorized that they would not have dared to visit the union office in any case. Finally, every man joining the Union was to be warned that he could not expect to secure any substantial improvement of his conditions until the campaign had advanced sufficiently and had succeeded in unionizing the bulk of the workers.

The underlying thought of the plan was that as soon as substantial numbers of the millinery workers joined the Union, were ready to act concertedly and in accordance with the principles and decisions of the union, they would by this very fact have gained economic status in the trade, becoming such an important factor that the manufacturers would be compelled to concede union conditions to them independently, whether these manufacturers did or did not recognize the union officially.

When this plan was first proposed it was almost laughed out of court. It was considered next to impossible to get new members to stick to the organization long enough until sufficiently large numbers had organized, if the union would not be able meanwhile to do anything substantial for them. When the plan was finally adopted, it was merely as an experiment and primarily because nothing else could do done. Even then it was considered so impracticable that no one was ready to volunteer his service on the committee which was to undertake this task, and appointments on the committee were accepted only grudgingly. It should be stated, however, that the organizer immediately in charge of carrying out this plan, Nathaniel Spector, now manager of Millinery Workers Union No. 24, put his heart into it, bringing into the campaign unusual zest, enthusiasm and energy.

The success of the campaign exceeded all expectations. Notwithstanding the fact that it was made clear to every worker that by joining the union he could not expect any protection immediately; that even in case he should be victimized for his membership in the organization he could not depend upon the union for reinstatement, except that every effort would be made to help him financially until he found a new job; and that he would have to stand by the union for a year or more before something substantial could be done for him, the union message met with an immediate and ready response. In several months the great majority of the workers of many individual shops joined the union. In all such cases these men conducted shop meetings at which the particular problems of their shop were taken up as well as the general trade problems, shop committees were elected and instructed to take up the workers’ grievances with their employers in an unofficial capacity.

How the Plan Worked

During this initial period of the campaign, we never asked for union recognition or for the signing of an agreement. Instead, the workers of the shop were instructed as to the wages and working conditions upon which they were to insist under the unofficial supervision of the shop committee. Neither did we let ourselves be provoked into premature strikes. There were many cases of discharge and discrimination because of union activity; the members of the unofficial nonrecognized union shop committee were especially singled out by the employers for victimization. In all such cases we would help them financially, frequently raising the necessary funds for levying an assessment upon their co-workers in the shops. We did not interfere when employers took new workers in place of the discharged. But under the pressure of the rest of the men in that shop the new worker, if he was not a member of the union, would soon join the union and would then behave exactly the same as the other workers of the shop, in compliance with the instructions of the shop committee and the union officers. To be sure, as the campaign proceeded and the proportion of union workers grew we did in special cases call shop strikes, but only when their success could reasonably be considered as more or less certain.

For almost two years the organizing campaign was carried on in this way and the entire district was fully organized. During this time substantial improvements in workers’ conditions and wages were secured. What is more, without any signed agreements whatever, without any union “recognition” by the employers, without any direct dealings of the union officers with the employers, and even without the officers of the union having admission to any of the shops, practically uniform working conditions and wages were established and maintained. These conditions were continually raised and brought up to a level which would stand comparison with the well organized trades having official union recognition and collective agreements. Of course, the manufacturers couldn’t fail to discover sooner or later that their shops were in fact organized and that the workers followed and carried out the instructions of the union. They couldn’t help feeling that in certain cases they involved themselves in unnecessary difficulties and delays. For the men in their dealings on price settlements would drag the dealings in order to report to the union officer and get instructions. If matters were urgent the manufacturers found themselves compelled to suggest to the workers that they call in the union officer and settle at once. Gradually many manufacturers came to the conclusion that it would be better for them to recognize the facts and deal directly with the union rather than continue the make-believe that their shop was still non-union. So one by one the manufacturers started to sign agreements with the union, though even at this time there was no collective agreement in the trade. As already mentioned, however, the degree of organization reached in this uptown district would stand comparison with the best organized trade.

The process of organizing on the basis of recognition by the workers and not by the employers, developed among the workers in every shop a strict discipline and an ability and practice of acting concertedly at all times in accordance not merely with instructions but with the very spirit of the union. It developed such an esprit de corps that it made it possible for the union to withstand many critical situations, and come out of such difficulties with strengthened positions much more successfully than many another strong organization which did not pass through such a school where the workers had to depend entirely upon their own ability to control the conditions in the shops.

Praised by Union Head

At the 1925 convention of the Cloth Hat, Cap and Millinery Workers International Union the President of the organization had this to say to the effect of the organization campaign described above: “It was Budish and nobody else who initiated the campaign of the millinery workers uptown. He was the initiator, he laid out the plans, wrote out the manifesto, and decided the policy how to organize. He coined the slogan ‘Recognition by the workers and not by the bosses,’ and that slogan organized the trade.”

There may have been a little over-emphasis in this estimate by the President of the International Union. There is no doubt, however, that dependence upon employers’ recognition makes the trade union helpless and impotent in the organization of the bulk of workers, and that if our organizing campaigns are to be made effective they must be based on this principle of recognition by the workers and not by the employers. So we are in a position to formulate another general principle and method:

Organizing campaigns must be based on union recognition by the workers. This means that the workers develop clear and conscious understanding of the indispensability of concerted action on their part and develop an ability to practice such concerted action individually and collectively. In this way, the workers gain economic status and control in industry and they do so independently of any official union recognition by the employers.

Whether such methods and plans can be applied to the basic industries demands further consideration.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v28n05-May-1929-Labor%20Age.pdf