The ‘Red Summer’ of 1919 lasted well into the fall that year, and beyond. Some might argue it has never left us. The so-called Centralia Massacre saw I.W.W. members defend their hall against American Legion thugs in a 1919 Armistice Day attack, resulting in the deaths of five reactionaries and the lynching of I.W.W. activist, and fellow veteran, Wesley Everett as well as long jail terms for heroic comrades and innocent bystanders. Eight years into their sentences, the solidarity campaign for their release was stymied by the split in the I.W.W. James P. Cannon, then secretary of International Labor Defense, visits the class war heroes in prison and filed this report.

‘A Talk with the Centralia Prisoners’ by James P. Cannon from Labor Defender. Vol. 3 No. 6. June, 1928.

OVER three hundred workers’ halls were raided by inspired mobs of “patriots” during the war and the year that followed it. When an armed mob attacked the Lumber workers hall in Centralia, Washington on Armistice day 1919, it met a group of workers who resisted and fought back. In the fight which ensued three of the raiders were killed, one of the lumber workers, Leslie Everest, was lynched and seven others were sentenced to terms of twenty-five to forty years in the State Penitentiary at Walla Walla, after a trial which was a legal lynching conducted in an atmosphere of terror and intimidation. The eighth man, Loren Roberts was adjudged insane without definite sentence although his sanity now is obvious.

I went to see them on my Western trip. I had been in correspondence with several of the men and they had invited me to come.

A visit with them is not soon to be forgotten. They belong to that wholesome Western breed of rebel outdoor workers— freedom-lovers and whole-hearted fighters; idealistic men who stake their heads on the things they believe in. Confinement bears heavily upon such men as they who are used to the forests and the open field.

Three of them have families waiting for them and dependent on them, with children growing up without the father’s steadying hand over them.

The Centralia prisoners have borne their martyrdom with a soldier spirit, but after nearly eight years in prison they are now beginning to put the question of a real effort to get them out in the most direct and pertinent manner.

“We are a part of the price paid for better conditions for the lumber workers,” said Eugene Barnett, a fine type of American rebel worker, whose life of poverty, hardship and struggle has been interestingly told in “The Autobiography of a Class War Prisoner,” which was published serially in the Labor Defender.

“We are here as an example to other workers. There is not a criminal amongst us. We are here in the cause of labor and we want a united movement of all the workers for our release. We do not see why all elements who are honestly devoted to the working class cannot unite on such an issue, even though they have differences on other questions. Those who take a different attitude do not represent our views or wishes”.

The others whom I talked to echoed these sentiments. They spoke these men with nearly eight years of imprisonment behind them–with bitter indignation about the factional wrangling over their case, the paralysis it has brought about and the failure to organize a united movement in their behalf.

We talked of many things in a crowded, hurried way. Did you ever visit men in prison? It is like a meeting between people from different worlds. There is so much to say, so many questions to discuss, and it must all be done within a time limit. The guard is waiting and every minute you expect the notice “times’ up!” Then the hurried words of parting, the hand clasps and the horrible clangor of iron doors slamming shut and the harsh, grating noise of the bars sliding back into the slots.

“We belong to the working class” said James McInerney, “and we want all the workers to know about our case and take part in the fight for us”. I was especially anxious to see McInerney, as I had heard much in praise of his character by those who know him. “When you see McInerney, you’ll see a man” a former prisoner of Walla Walla told me at Portland.

I suggested an attempt to get support from the trade unions and farmers in the State and also from some liberal and humanitarian elements, and they agreed with that. There is no sectarianism in their attitude.

“The thing that burns a man up in a place like this,” said McInerney, “is to see your own kind who are sup- posed to be closest to you, doing absolutely nothing for you and acting as though you were a bone to fight over.

“Eight years of another man’s life. in prison is a mere trifle for some people but for the man who serves the time it is a very important matter. These eight years have been the best eight years of our lives. It was our service to the cause of the workers that brought us here, not any selfish purpose, and we don’t want anybody to stand in the way of a united movement of the workers to get us out”.

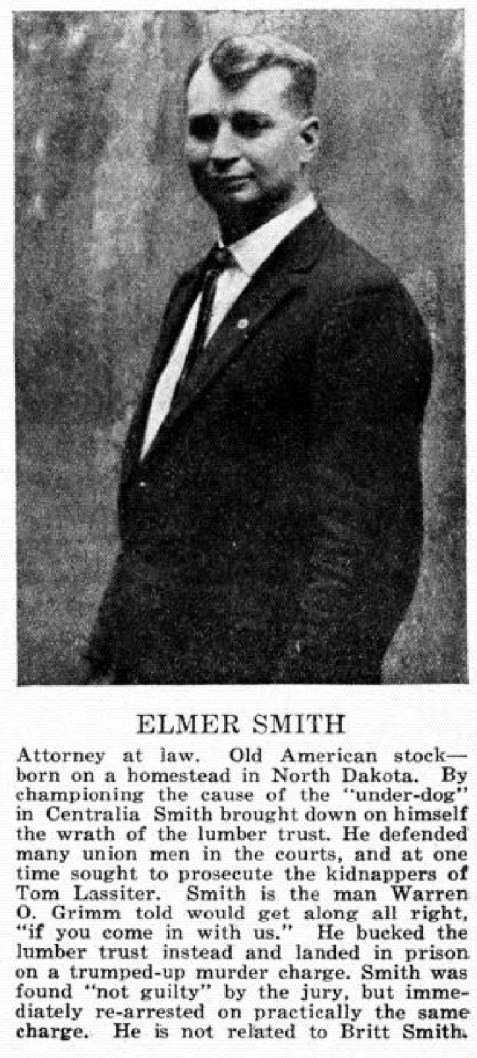

I told them I had talked with Elmer Smith and at the mention of his name, the conversation switched around to him. He has first place in their hearts, and for good reasons.

The tireless work and selfless devotion of this Centralia lawyer in behalf of the eight lumber workers at Walla Walla is a big story in itself. He was a young lawyer in Centralia with bright “prospects”, but he had antagonized the monied interests by his friendship for the workers and his attempt to defend their legal rights. When the Armistice day tragedy occurred the Lumber interests set out to “get” him and he was indicted and brought to trial along with others.

Since the day of his acquittal, nearly eight years ago, he has worked and fought unceasingly for the release of the men who were convicted. He has made a National speaking tour the case and he has carried the issue into the most remote rural corners of the State of Washington in long campaigns. Moreover he stuck it out in Centralia the scene of the fight, facing the ostracism, boycott and threats of the whole crowd of lynchers and framers, and finally winning over the great majority of the people of Centralia to the cause of the prisoners.

Serious illnesses and several operations have only been interludes between his strenuous campaigns and when I saw him at Centralia he was hard at it again, although still weak from a recent operation. He is working now on a petition of Centralia citizens for release of the men.

It is the work of Elmer Smith more than anything else which has kept the Centralia case alive. This has been especially true since the split in the I.W.W. when the Centralia case was dragged into the controversy and activities in their behalf were paralyzed to a large extent.

The prisoners were the football in that football game and their wishes for unity of action got scant consideration. The rank and file of the I.W.W. has always been loyal to the Centralia martyrs, but for many little office holders in both factions the case ceased to be an issue of the class struggle and became a private business.

The only activity of any consequence I could discover on my trip west was that conducted by the Centralia Publicity Committee with which Elmer Smith is connected. Its work is concentrated at present on securing a petition of Centralia people. This is good, but a broader and bigger fight must be organized.

“Nothing but a general strike will free the class war prisoners” is a remark one hears quite frequently. There is no doubt that a general strike is a powerful weapon, but in the period when the conditions for the strike are lacking this slogan can easily become a cloak for passivity and for neglect of those forms of protest action which are possible under the circumstances. It is the task of conscious workers to organize those small actions which are now possible- meetings, petitions, pamphlets, conferences, etc., and to strive to develop them into higher forms of class action. Passivity in these forms of class action under present circumstances amounts to betrayal of the class war prisoners.

The “Labor Jury” selected by the trade unions of the state which sat at the trial voted “not guilty” unanimously. Seven of the jurymen who convicted the men have since admitted they have appealed to the Governor to pardon them. Elmer Smith told me 85 per cent of the people of Centralia would sign the petition for pardon. A well-organized campaign, uniting all forces, would gain tremendous support which could not be disposed of easily.

The prisoners themselves who are the final determining factor have said their word very decisively. Their open letter to the International Labor Defense which is being published in the press appeals clearly for a united movement in their behalf.

It is the duty of all labor militants to see that this appeal has not been made in vain.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1928/v03n06-jun-1928-LD-ORIG.pdf