An excellent three-part expose on working class Pittsburgh by Socialist Party activist Bertha W. Starkweather and the brutal, often fatal, conditions faced by largely Eastern European workers, derisively call ‘hunkies’ (later morphing into the epithet ‘honky’), in the steel mills and other industries of western Pennsylvania, a center of working class struggle in the U.S.

‘The Pittsburg District’ by Bertha Wilkins Starkweather from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 10 Nos. 10, 11, 12. April, May, June, 1910.

I.

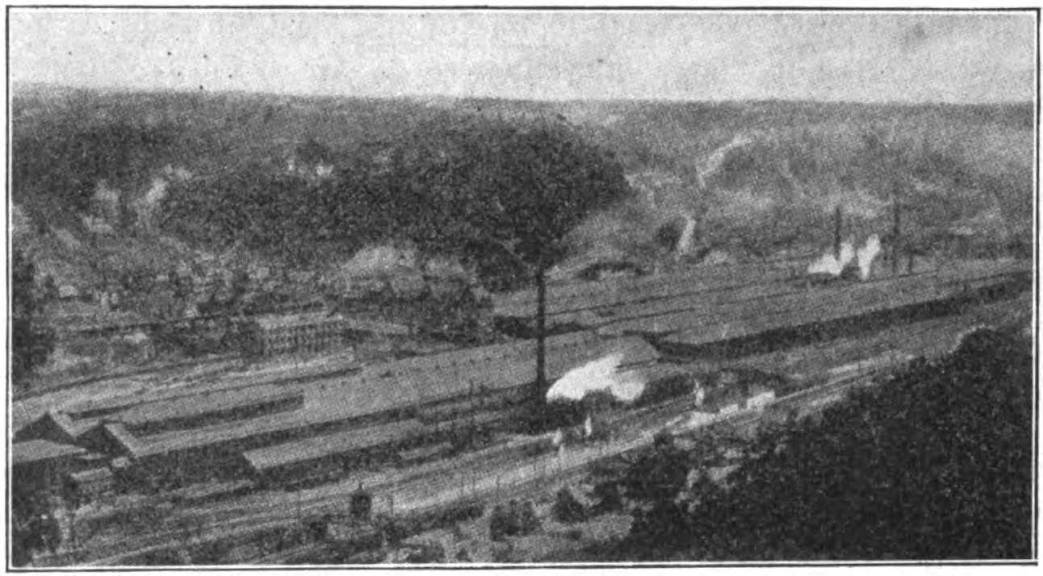

WITHIN a radius of forty miles from the city of Pittsburg a great number of various kinds of industrial plants are to be found. Here Nature furnished lavishly the elemental materials which man has learned to turn to his use in producing what he desires for his needs.

Two beautiful rivers winding westward through picturesquly wooded hills, joined forces and the larger stream which resulted, the Ohio River, became the great water highway between the middle states and the West. “The Point” at the head of the Ohio has become strategically and commercially of vast importance.

The Pittsburg District, eighty miles in diameter, boasts of leading the world in the manufacture of iron and steel, tin plate, air-brakes and electrical machinery (both Westinghouse interests), coal and coke, fire brick, plate-glass, window glass, tumblers, tableware, pickles (Heinz’s 57 Varieties and other pickle factories), sheet metal, white lead and cork. Each of these plants is conducted along sweatshop lines. All possible work is done by machinery anti unskilled workmen form the greater part of the working force.

The great factory producing Heinz’s 57 Varieties, is one of the boasts of the city. It is in every way a well-conducted, clean institution, where all things are well cared for except the poor foreign girls who do most of the work. The company gives these girls a lunch room, rest room, roof garden, a theatre and assembly room containing stained glass windows —in fact, it gives them everything except good wages.

In nearly all other institutions conditions are worse because the factories are dirty, unhealthy places. Sweatshops there are of every stage of sordidness in this great industrial maelstrom.

The Heinz pickle factory certainly surrounds the workmen and women with conveniences and comforts and insures to the consumers clean articles of food. Under a rational industrial system, the workers would work three hours where now they labor ten and they would work with even better machinery than the Heinz factory employs. With hours shortened and wages up to full producing power, surroundings pleasant and stimulating to faithfulness and cleanliness, the great work of the world might be done without suffering to any class.

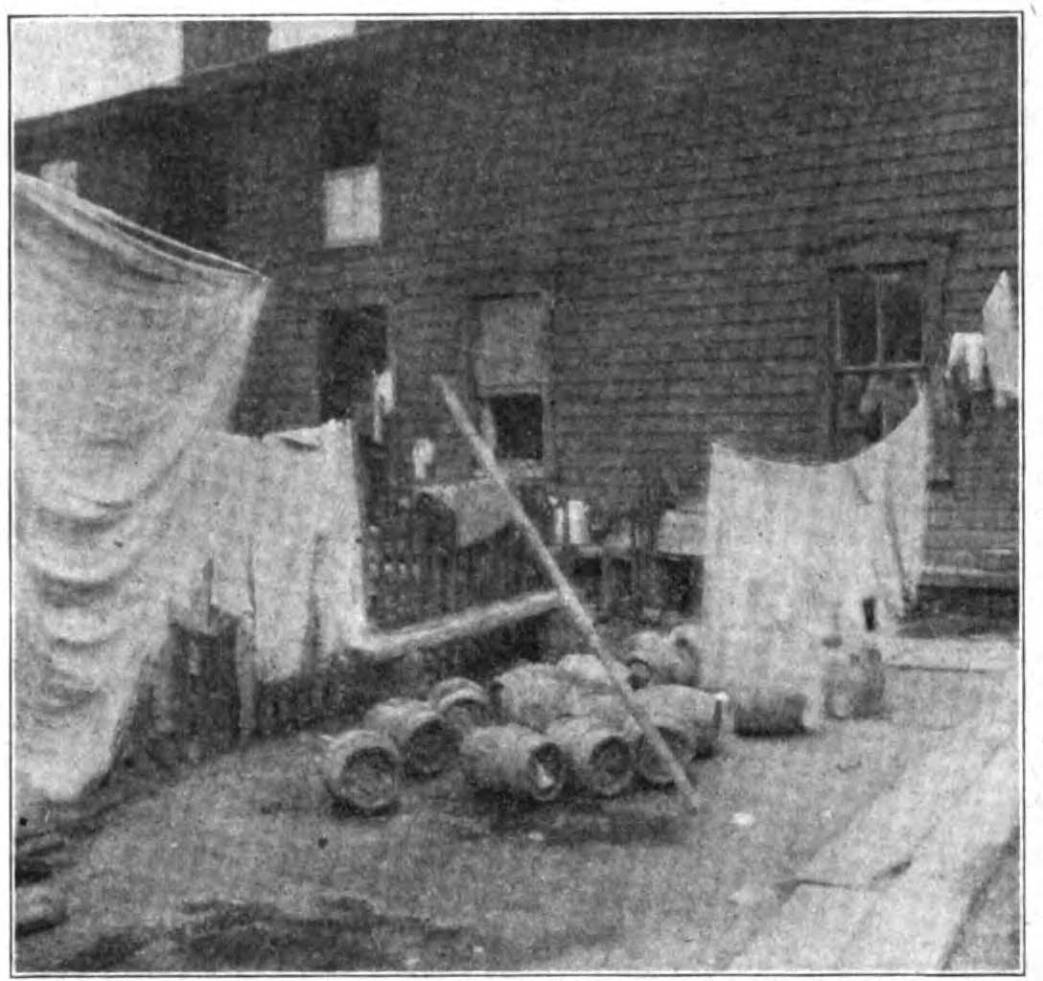

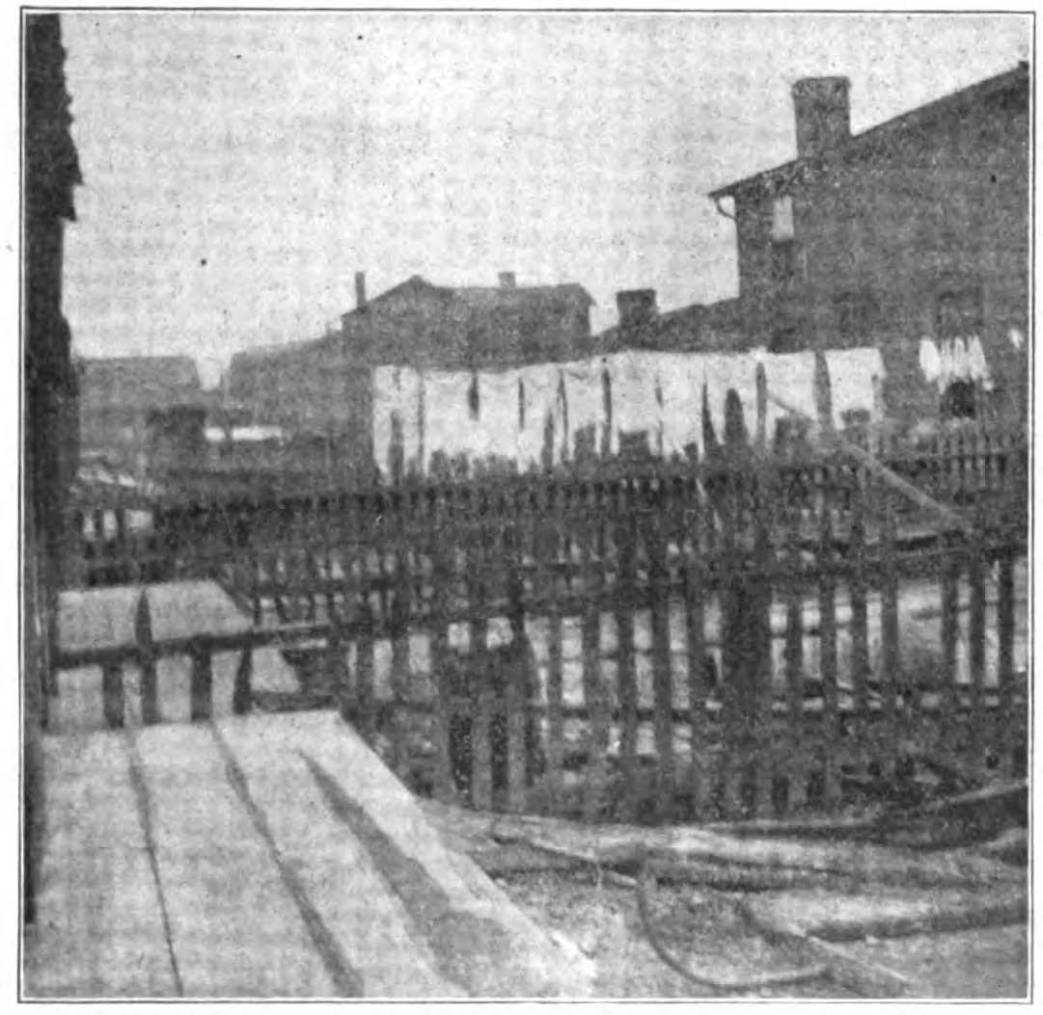

As it is, the plague of the slum is upon this industrial center so that the civic clubs of the city are trying in their gently reformatory and apolegetic way to remedy matters by establishing a bath here, and a settlement there, in a vain attempt to “save” the children of the slums.

Because of all the smoke stacks belching forth black soft coal smoke, Pittsburg is literally over-shadowed. The heavy pall of smoke from the mills alone would shut off the sun for many weeks in winter. The air is heavy with a marrow-freezing chill which is hardest to bear by the poor, half-fed working men and women as they go to work early and return late. This cold, darkness of the winter days and the sickening heat of the summer months seems to have a distinct psychological effect upon the inhabitants of the working districts of Pittsburg. The per cent. of suicides is unusually high.

“This dark, cold weather with the rents so high, and the living so high and the men folks always having trouble with the bosses, is enough to make a woman do the Dutch!” exclaimed a steel-worker’s wife as she set her washboard into her tub of hopelessly soiled clothes. “You don’t know what ‘Doin’ the Dutch’ means? You must be a stranger in Allegheny! Why, it’s committin’ suicide, that’s what it means and if you happen to have a helpless child or two to leave out in the cold world, you take ’em along so they won’t have to suffer without your care. That’s ‘doin’ the Dutch’. Everybody knows that—and lots do it, too. You can see by the Coroner’s books. I’ve been witness at two inquests right in this neighborhood. Goodness knows, I didn’t blame the poor things.”

There were 189 suicides in Allegheny county in 1907 (good times). In that county, too, the coroner reported 64 murders.

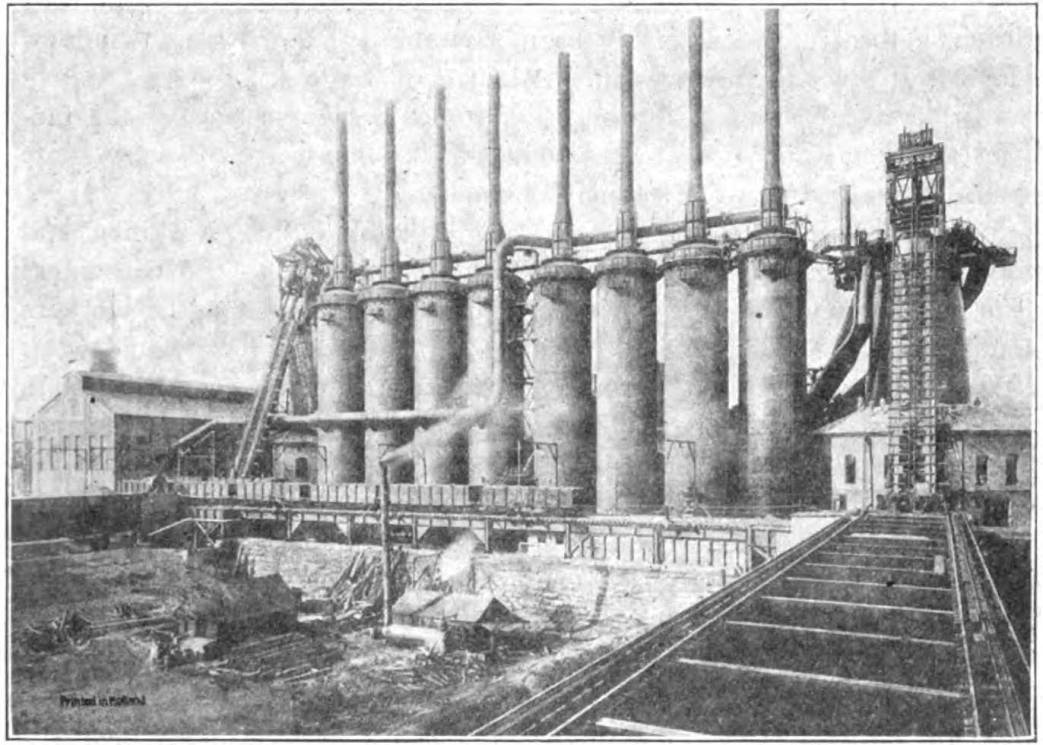

As the output of a steel plant depends upon the number of its blast furnaces, it is a significant fact that the Pittsburg District has 103 of these furnaces, whereas South Chicago contains eleven and the new plant at Gary, Indiana, is said to be planned for thirty.

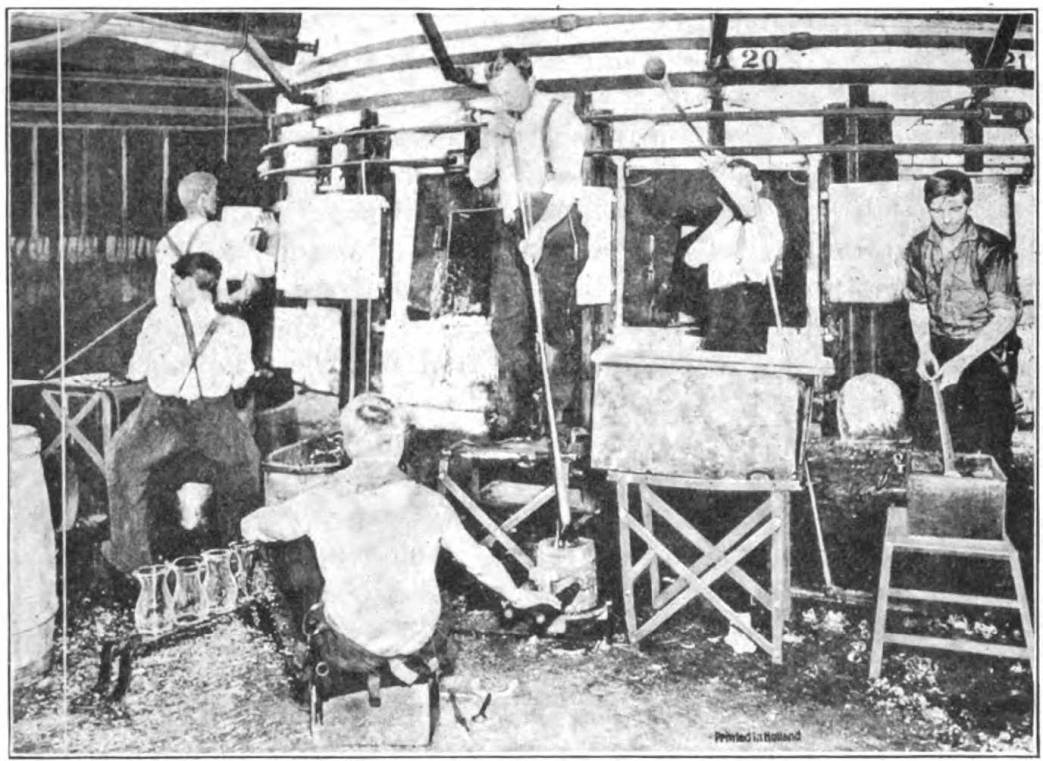

“The Pittsburg District” is a great department factory in the production of steel. At Homestead the specialties are rails, armor plate and structural steel for buildings and bridges; at Duquesne, rails and billets; at McKeesport, tin plate and pipes are specialties; at Wilmerding, air-brakes (Westinghouse); Turtle Creek, also a Westinghouse property, makes electrical machinery where one may see several thousand girls in a single room winding armatures. These plants are all sweat-shops in that they are merciless in squeezing as much from and giving as little as possible to the workmen. The Westinghouse air-brake works at Wilmerding illustrate modern methods of speeding as applied to the making of the many small parts of steel or brass that are needed in air-brakes. The great place was hot; metal was being poured into small moulds on all sides, one day when I visited the plant.

“What does that boy get in wages for making those small brass castings all day,” I asked of the guide as we passed along and stopped to see the young workman tip the ladle full of melted brass, which moved on a little track overhead.

“I think he gets about a dollar and a quarter per day,” said my guide.

“The men get more. They make larger castings and it is harder work. Some of the Hunkies get a dollar sixty or a dollar eighty per day.”

They were all working, hot and sweaty for many hours, casting the parts of the air-brake systems in this great sweat-shop which is hailed all over the world as a model workshop. There was one man who had the job of pulling down a lever to release a set of little castings from their moulds. A workmate said he had been pulling down that handle for twenty years—just one stroke of the two arms over and over and over for twenty years for a little less than two dollars per day. All around was just such slavish toil; no man could feel glad to be doing such mind-dwarfing labor all day only to drag his aching body home at night to prepare for another tragedy the next day. But it is vain to thing of the ideal of work which William Morris gave us—that it should be worth doing, that it should be pleasant to do, etc. Wherever one goes in this great center of industry, one finds the same slavish toil holding the men as in a straight- jacket.

Twelve miles down the Ohio River in a northwest direction from the Point, is the new town of Ambridge, the plant of the American Bridge Company. Three years ago. the soft hills of Pennsylvania rolled down to the Ohio invitingly, where now Ambridge stands. It is “made” by the American Bridge Company and every man who lives there is in some way connected economically with the Bridge Company. Ambridge is crossed by a hundred railroad tracks covered by a great bridge which connects the bridge works with the great office building and the town.

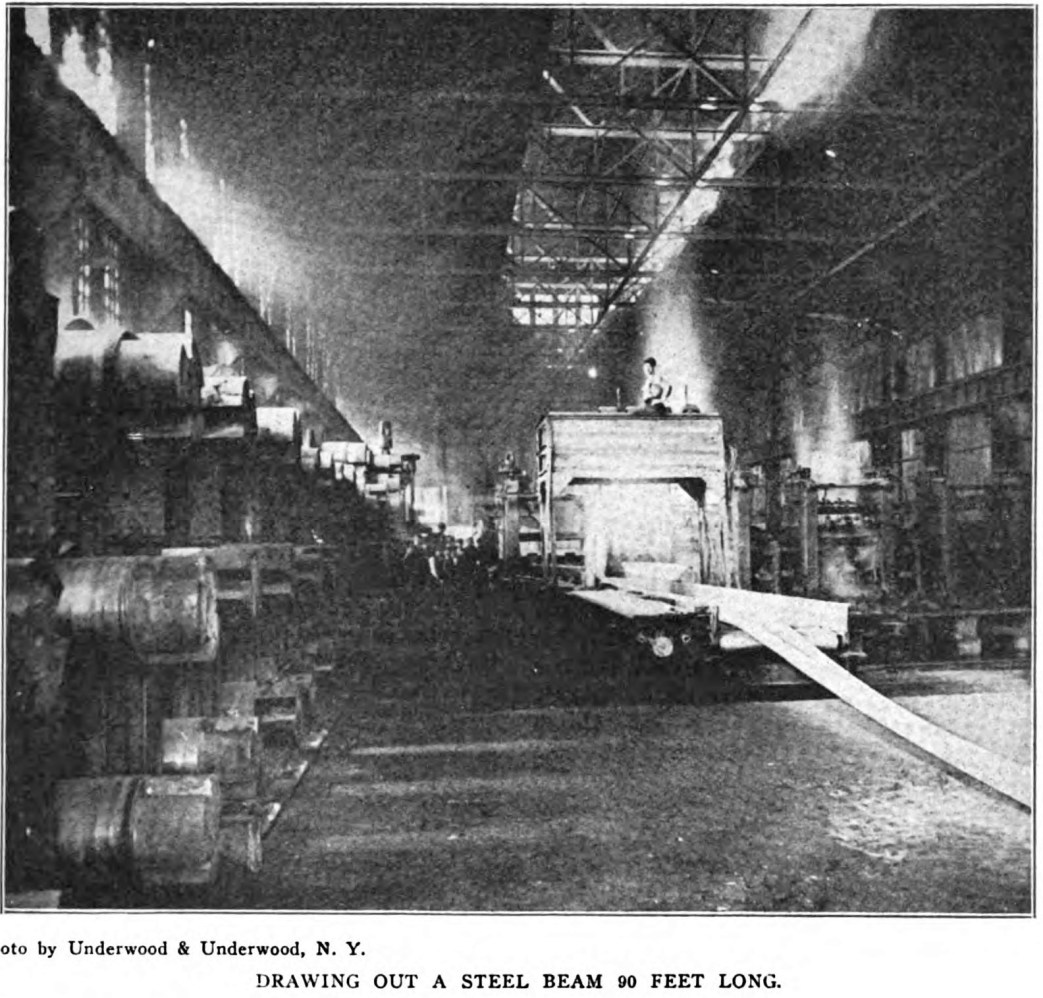

From Homestead they run the structural steel into the Ambridge plant, in the rough. Here it is prepared for riveting, dipped in paint, every part carefully marked and all parts tied together as they will be needed by the bridge builders. High towers in the works mark the places where the places where the great girders, over a hundred feet long, are handled.

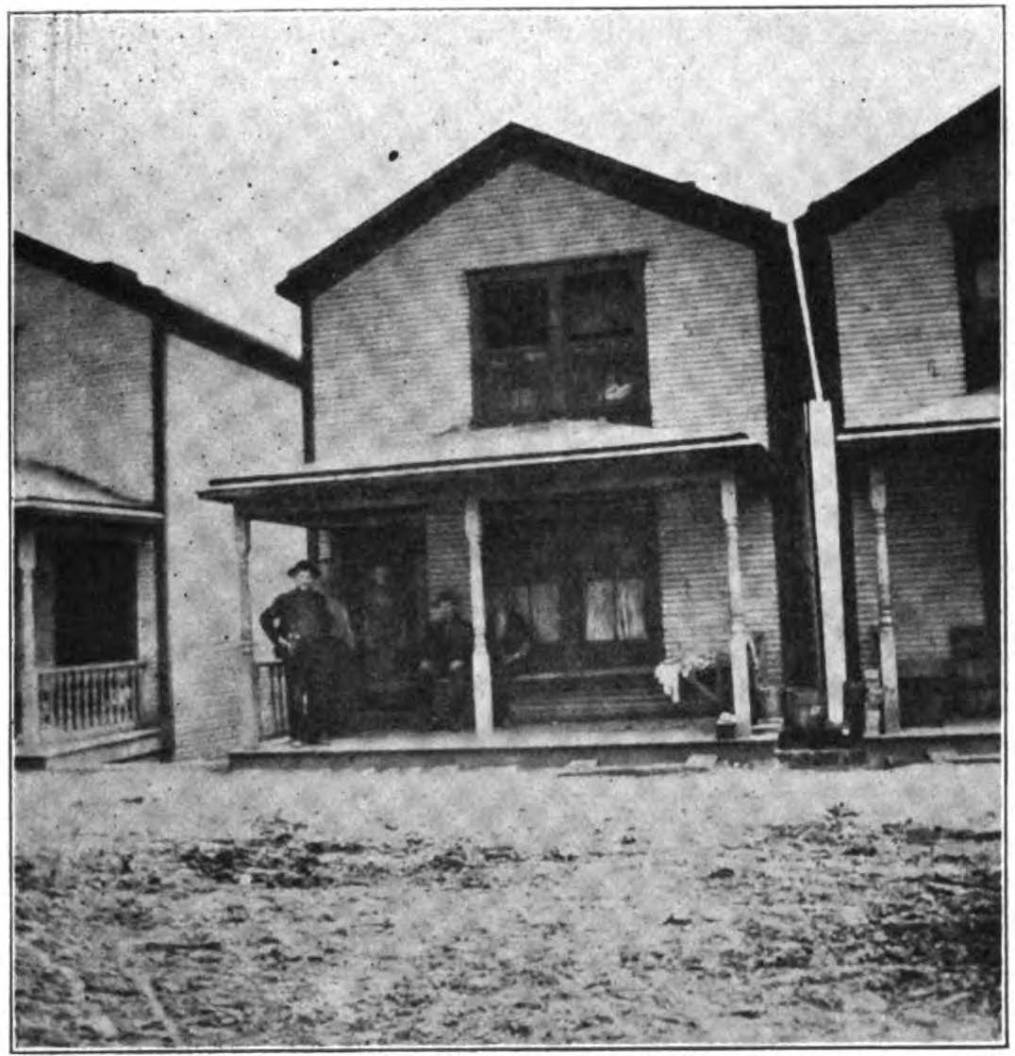

The evening before my visit an accident happened killing two men and injuring eight others. One of the long girders had slipped, that was all. It happened at six P.M. and even the coroner was not admitted when he called to inquire into the cause of the accident. At two o’clock on the next day, I went to see Hunkey town in Ambridge—as wretched and mean a place as a very new slum can manage to become in so short a time. There were rows of crowded tenements and other long rows of box-like houses, all containing four rooms. Every room swarmed with foreign workmen. In some cases the beds never grow cold, as they are used by day and night shifts in turn. The workman who could speak a little English told me that upstairs in one of those crowded rooms lay one of the seven men who had been injured by the accident of the evening before. His neck had been deeply lacerated, almost cutting the jugular vein. They told me that he was wild with delirium. They were waiting for the company doctor, who had promised to come at three o’clock. The little hospital of two rooms inside the works’ enclosure had been too full to give him a berth when he was hurt, so they sent him “home.” And eighteen hours later the company doctor was being expected to care for the wounded man in the foul room which he shared with four other men.

In 1905 the United States Steel Corporation paid the sum of $128,900,000 in salaries and wages, in spite of the fact that more than one-half of its men are paid laborers wages—fifteen to twenty-five cents per hour— for dangerous work. Yet the Captains of Industry look with jealous eyes upon this “wage budget” and the limit of displacing labor by machine work seems farther away than ever, as new labor-saving inventions are constantly being made. Usually these inventions are the products of workmen themselves.

A few years ago an attempt was made to employ colored workingmen instead of foreigners because of the many costly accidents occurring where the men did not understand the language shouted by the bosses. When the boss cried “Look out!” the luckess Hunkies stood still, blinking stupidly and shrugging their shoulders, only to be caught by flying metal or switching cars. So a gang of fifty colored men was detailed to the furnaces shoving ore buggies. They pushed the empty little cars down the incline willingly enough but when the boss told them to take the loaded cars back, they stopped and the spokesman, a great giant in bronze, asked smiling quizzically:

““Where’s the mule, boss?”

“Ain’t got no mule!” howled the boss, “Get a hold there you fellers and push ’em along!”

“Well, boss, I see You’s mistaken about mules. If I is hired to do mule work, I quits right heah. We alls goin’ to balk, that’s alf.”

So the fifty colored men filed out of the mill yards carrying their full dinner pails in their hand. Our colored brothers do not seem to make such willing wage slaves as might have been expected. The Steel Company seems to have taken a hint from the colored giant. In most steel mills ore-buggies have been replaced by automatic charging machines and the “mule” is a splendid electric motor. This innovation has thrown a thousand Hungarians out of work in a single plant, but anyone familiar with the inhuman conditions under which these poor fellows had to work, cannot but rejoice that the work is now done by machinery. On each alternate Sunday these Hungarians worked a twenty-four hour day.

When they complained they were given the alternative of submitting or taking their “time.”

The Coroner’s report of men killed in mill accidents is very noncommittal. The names of the witnesses are usually foreign and the jury “failed to get evidence sufficient to decide as to the cause.” When an employe who had worked for many years in a dangerous department of the mills was asked for information on the causes of accidents and the coroner’s proceedings later, he said.

“Yes, they hold those fake inquests over us AMERICANS where questions would be asked; but we think that some never do get inquested.”

“Do you mean to say that they break the laws and bury the dead without permits?”

“Why, after one of these big explosions, a man may be fairly engulfed in white-hot metal and then nothing is left to hold an inquest over. There is no question of a burial certificate, because there is nothing to bury. How can you hold an inquest over nothing? So the boss of the gang may say that he has immigrated and his fellows who escaped injury, keep still at peril of their lives or their jobs, which amounts to about the same thing. The men who really know about the accident are not called in as witnesses before the coroner’s jury.”

With a population of forty million people, England injures less than a hundred thousand and kills about a thousand a year. With a population of eighty million, the United States injures a million and we do not care to let the world know how many of these die.

There is a report among the men, that a few years ago three Austrian workmen disappeared in the mill yards in South Chicago, like the animals that went into the lions’ den and never came out. It was said that the Austrian consul blustered and threatened to get indemnity. But the men say that the mills have a prescription for even severe cases of righteous indignation.

The most frequent accidents occur at the base of the blast furnaces. A workman told of an accident in which several men were killed. The foreman called into service a dump-cart. In this the dead were taken to the hospital. A passer-by, it is said, heard the groans of one of the victims. He noticed that the driver and his assistant were about the dump the mangled human bodies out as if they were scrap-iron. But the common citizen was not yet hardened to the ways of steel. He came forward and cried:

“You take those bodies out like humans, one by one, or by heavens, I’ll shoot you down as dead as the deadest man in the load!”

They found the groaning man at the bottom of the pile.

Where a few years ago ore was shoveled by men, it is now taken from the hold of the ship by means of a great arm of steel. This arm takes fifteen tons of ore in an immense double handful, on the principle of ice tongs, and affords a saving of two thousand dollars on each shipload of ore. Of these grabs these are almost a score in the South Chicago plant. Sometimes a dozen grab hooks work at the unloading of a ship and this means a great saving of time for the services of the ship. The conveyors, great bridge-like carriers, then bear the ore to the blast furnaces.

II.

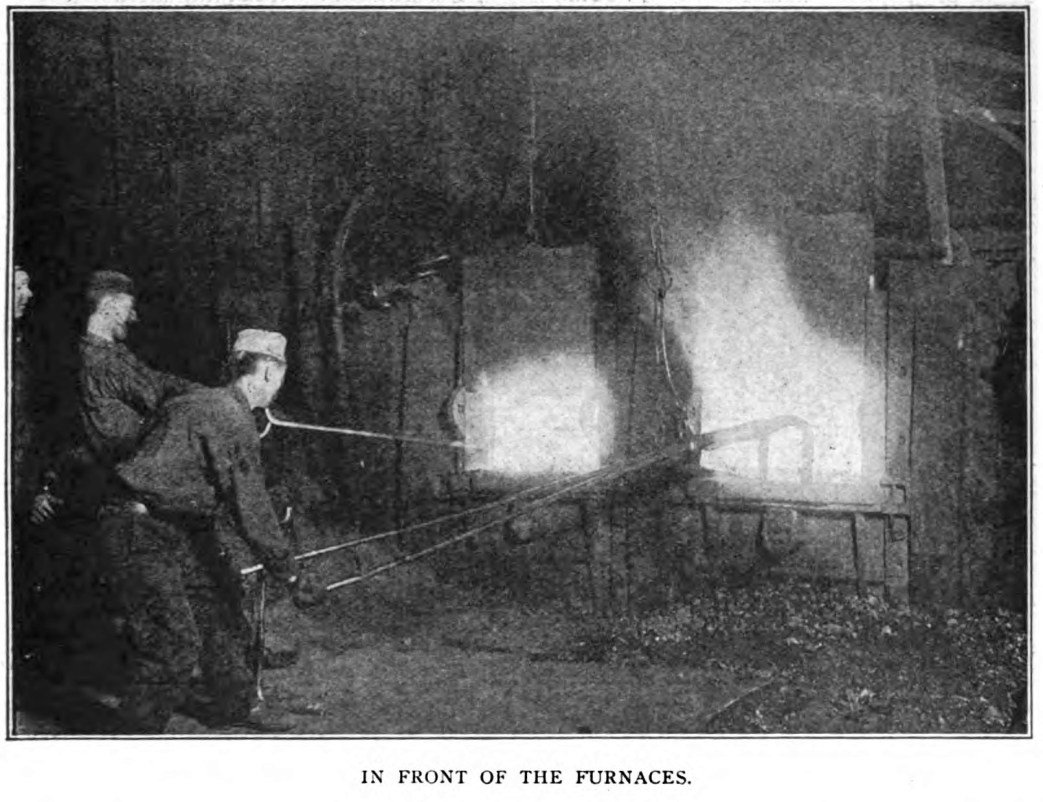

IN THE Pittsburg District the speeding of machines and of the men in charge, is merciless. The rule is to produce to the limit of human endurance. It is easy to overestimate what these great machines will stand. Accidents are usually caused by over charging. An overcharged blast furnace acts a good deal like an overloaded gun. Many tons of half-molten ore and coke sometimes become clogged above a little lake of hot metal and burning gas. This “hang” must be loosened by workmen from above.

When the “slip” occurs, the great mass of overcharge falls into the seething hell beneath. Then an explosion is likely to occur, too horrible to describe. Either the charge is hurled upward with terrific force carrying death and destruction as it flies, or it may, without a moments warning, tear away the heavy masonry of the furnace below and set free the mass of metal at the bottom of the towering fire brick structures. Overcharging is simply carrying the speeding process one notch too far.

An old, worn-out blast furnace is more likely to produce a “hang” than the new fire-brick-lined ones in good condition. But it takes six weeks for these furnaces to cool off to rebuild the fire-brick-lining.

So the work is often put off until an explosion makes rebuilding a necessity.

William Hard, says in “Making Steel and Killing Men,” an article appearing in Everybody’s Magazine, November, 1907:—“The only death dealing force that exceeded the railroad last year in the Illinois Steel Company’s plant, was the blast furnace…on the ninth of last October at about ten o’clock in the evening, Walter Steinmaszyk, a sample boy, went to one of the blast furnaces to get a sample of iron to take to the laboratory. He stood at one of the entrances to the platform. The bright liquid iron was running out of its tapping hole, and flowing in a sparkling snarling stream along its sandy bed to the big twenty ton ladle that stood beside the platform on a flat-car. Walter Steinmaszyk stood still for a moment and gazed at this scene. It was well for him that he hesitated. Suddenly, there came a flash, a roar, and a drizzle of molten metal. Milak Lazich, Andrew Vrkic, Anton Pietszak and Louis Fuerlant lay charred and dead on the casting floor.

“What was the cause of the accident?

“The expert witnesses employed around the blast-furnace, all agreed that the hot metal had come in contact with water.

“And how did it come in contact with water?

“Here, again, the expert witnesses were in agreement.

“About two months before the accident, the keeper of the furnace had called the attention of the foreman to a little trickling of water around the tapping hole. An examination was made and it was found that some of the fire-brick at one side of the tapping hole had fallen out. The foreman reported this fact to his immediate superior. But the fire-brick was not replaced. Patches of fire-clay were substituted for it. These patches were renewed from time to time. They wore out very rapidly.

“On the night of the 9th of October according to all the experts at the trial, the fierce molten iron ate its way through the fire-clay and came in contact with the water coil. The union of the hot iron with the water resulted in the explosion and in the Sacrifice of four human lives…If the company were offered a prize of a million dollars for getting through a year without one single fatal accident, would it then allow patches of fire-clay around the tapping hole of any furnace in its plant? Would it not find a way to prevent such make-shifts methods effectually and finally?”

The Iroquois Blast Furnace, owned and operated by a small company outside of the trust, producing pig-iron for the open market, is never speeded to the point of lowering the very high grade of iron that it turns out and because there is no speeding the “slips” which are so common at the steel mills because of over-charging, never occur. The blast-furnace therefore is not dangerous under normal conditions.

Every man killed at those furnaces, is simply murdered by the Steel Trust, for profit.

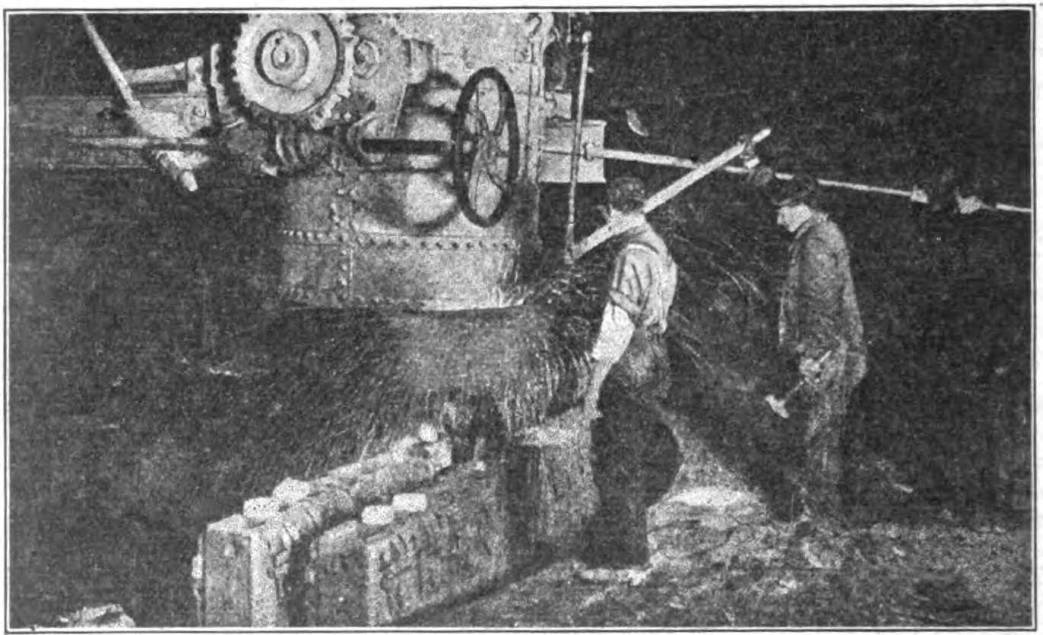

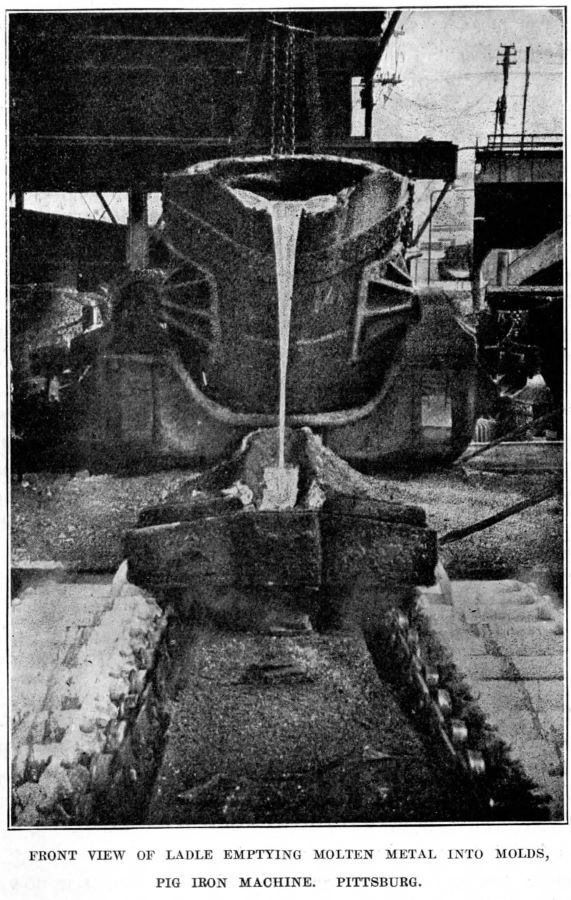

The metal from each “heat” or furnace full of coke, limestone and iron ore, is tested and then sent in open ladles to be converted into steel. These ladles are carried on trucks attached to little “dinky” engines. This pig-iron must be decarbonized, i.e. freed from carbon, sulphur phosphorus and other impurities, to become steel. There are two processes. At the Besemer converter plant compressed air is blown through the molten metal; the combustion, which follows, brings the heat up to 3200 degrees. In three minutes, thirty thousand pounds of iron becomes steel by this Bessemer process, reducing the cost of making steel, from seven cents to less than one cent per pound.

In the Chicago plant there are three of these great brick-lined, pivotted vessels about thirty feet high. Each converter has a capacity of from eight to ten heats an hour, fifteen tons to the heat. The men working at the base of the converter, are in constant danger of losing life and limb; if by some mistake the fire-clay perforated bottom through which the air is pumped is not quite dry; if by any chance there be water in the bottom of a box of scrap which is sometimes mixed in with the iron ore, then an explosion results engulfing the men at the base of the converter in metal. These slag men are usually Hungarians who do not know enough English to run for their lives if the foreman has time to shout danger.

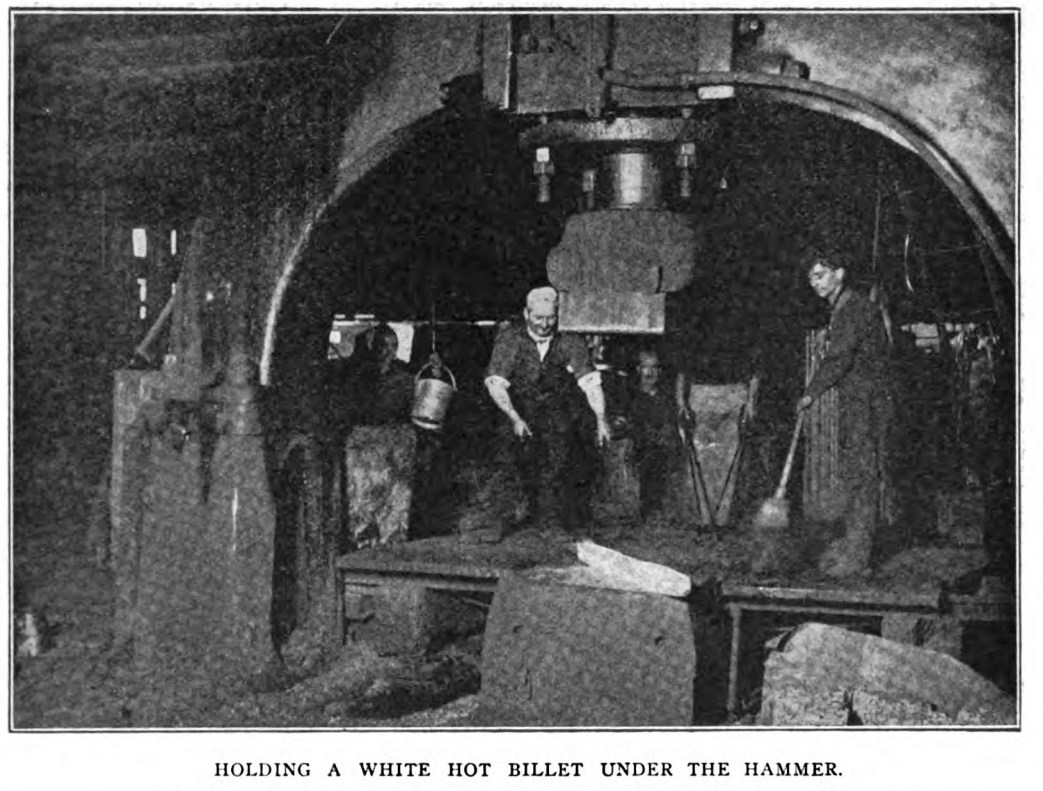

From the great converters, the metal is poured into a ladle and at the same time a little ladle runs out on a higher track in a saucy, mysterious way pouring a smaller stream of tempering mixture of manganese etc. into the great ladle below; this decides the hardness of the steel.

At the Homestead plant, the primitive method of tempering mixture is used “dry” and shoveled into the indescribably hot depths below by a workman who stands a few feet from the great converter as it is tipped to pour the stream of steel into the ladle below. From eight to ten times an hour this man works hard shoveling chemicals face to face with heat so intense as to beggar description.

For northern climates, the rails must be much softer than those used in the south, where there is no frost to crack them under the heavy weight of trains.

After the metal is tempered, it is ready to be poured into moulds. A great hydraulic lift, moves it around smoothly to the other side of the building, where the moulds are filled with the metal. There are seven of these moulds on each truck car; each mould will hold steel enough to make four steel rails. These moulds are inspected before they enter the building. and yet accidents occur. A few years ago one of these moulds was half full of water when the hot metal was poured, and sixteen men fell victim to the frightful explosion.

“It was like the very crack of doom,” a witness related. “We are used to danger and yet that sight haunts my dreams to this day. Men lay around here thick, all charred and scorched and most of us were too bewildered to get to work with the dead and the dying for a while.”

It is amid scenes of such hideous danger, that the steel corporation, in order to get labor cheaply, employs men who do not understand what is being said and done.

When the seven moulds have been filled they are taken out by the little engine and left to cool under the “stripper”. Here water runs over the outside of the moulds which cools and contracts the metal within. In a few moments iron hands from above lift the moulds from the bright red ingots of steel and they are ready to be run into the rail-mill, or girder mill or plate mill, etc., as the case may be.

Recently another process, less dangerous to the workmen in the production of steel has come into favor. Great as was Bessemer’s invention which revolutionized the iron industry in the early sixties, the quality of steel thus produced is unsuitable for many purposes.

For the production of a high grade of steel the open hearth furnace are coming into general use. By this process the metal is decarbonized by boiling it from twelve to eighteen hours. The result is steel for guns, tools, etc. In the Southern mills in Alabama, steel rails are made by this process. There is less danger for the men at the open hearth furnace although accidents are frequent and the heat is so intense that prostrations are of common occurrence.

The ladle trains with their white-hot metal, running at a fair rate of speed from blast furnaces to converter or to open hearth furnaces are another source of danger to the workmen. These great cups often “slop over” in spite of the thin layer of graphite which is sprinkled on top to prevent the spill. If this white-hot metal happens to strike a puddle of water along the track, it explode like a cannon shot. If it happens to hit a luckless switchmen, he has a deep flesh wound which often require skin grafting before it will heal.

“They used a good many inch of skin on my leg to make it heal,” an injured switchman remarked.

“Where did they get the skin?” was asked.

“Oh, a man had his arm amputated and they took the skin from that,” was his gruesome reply.

In the before-mentioned article which appeared in Everybody’s Magazine, William Hard give the history of a typical accident in the mills.

“Ora Allen is inquest 39,193 in the coroner’s office in the Criminal Court Building downtown. On the twelfth of last December he was a ladle man in the North Open Hearth Mill of the Illinois Steel Company in South Chicago. On the fifteenth he was a corpse in the company’s private hospital. On the seventeenth his remains were viewed by six good and lawful men at Griesel & Sons undertaking shop. The first witness, Newton Allen, told the gist of the story. On the twelfth of last December Newton Allen was operating overhead crane No. 3 in the North Open Hearth Mill of the Illinois Steel Company. Seated aloft in the cage of the crane, he dropped his chains and hooks to the man beneath and carried pots and ladles up and down the length of the pouring floor.

That floor was eleven hundred feet long and it looked longer because of the dim murkiness of the air. It was edged all along one side by a row of open hearth furnaces, fourteen of them, and in each one there were sixty-four tons of white hot iron, boiling into steel. From these furnaces the white hot metal, now steel, was withdrawn and poured into big ten-ton moulds, standing on flat cars. When the moulds were removed, the steel stood up by itself on the cars in the shape of ingots. These obelisks of steel, cool to solidity on their outsides, still soft and liquid within, were hauled away by locomotives to other parts of the plant.

“It was a scene in which a human being looks smaller than perhaps anywhere else in the world. You must understand that fact in order to comprehend the psychological aspect in steel mills.

“On the twelfth of last December, Newton Allen, up in the cage of his hundred-ton electric crane, was requested by a ladleman from below to pick up a pot and carry it to another part of the floor. This pot was filled with the hot slag that is the refuse left over when the pure steel has been run off. Newton Allen let down the hooks of his crane. The ladleman attached those hooks to the pot. Newton Allen started down the floor. Just as he started, one of the hooks slipped. There was no shock or jar. Newton Allen was warned of danger only by the fumes that rose toward him. He at once reversed his lever and when his crane had carried him to a place of safety, he descended and hurried back to the scene of the accident. He saw a man lying on his face. He heard him screaming. He saw that he was being roasted by the slag that had poured out of the pot. He ran up to him and turned him over.

“At that time,” said Newton Allen in his testimony, “I did not know it was my brother. It was not till I turned him over that I recognized him. Then I saw it was my brother Ora. I asked him if he was burned bad. He said no, not to be afraid, that he was not burned so bad as I thought.”

“Three days later Ora Allen died in the hospital.

“Why did the hook on that slag pot slip?

“Because it was attached merely to the rim of the pot and not to the lugs. Lugs are pieces of metal that project from the rim of the pot like ears. They are put there for the purpose of providing a proper and secure hold for the hooks but they had been broken off in some previous accident and had not been replaced.”

The company will tell you, very straightforwardly and very honestly that it is impossible to prevent the men from being reckless; that it is beyond human power to prevent the men from hooking up slag-pots by their flanges. The men get in a hurry and become careless…But suppose, just suppose, that instead of being relieved from all money liability by the carelessness of a ladleman toward a fellow ladleman, suppose, just suppose, that the company had to pay a flat fine of twenty thousand dollars every time a ladleman was killed. Do you think that any slag-pot would ever be raised by its flanges? That is the real question, and the answer is “No.”

III.

SUCH has been said of the high wages paid to steel workers. The fact remains that only about ten per cent. receive more than laborers’ pay which is from fifteen to twenty five cents per hour. In positions of great responsibility and danger, “expert wages” are paid to the men in charge. These are based on the tonnage so the wages depend upon the output of the department. They range from three to eight dollars per shift of eight hours.

The common workman at the base of converter or blast furnace working in a constant rain of sparks, with streams of white metal on all sides, is the veritable lamb for slaughter. Yet the competition among the unskilled workmen is often so great that they are willing not only to bribe officers and foremen in order to get a chance to work, but they are careful to keep those bosses “goodnatured”.

Since 1897 England has had in operation a law known as the fellowservant act. Under this law, the employer is responsible for accidents which occur because of the ignorance or carelessness of employes. The dependents of a workman thus killed are compensated for the amount of the man’s wages for the three years just preceding the accident. If he has not been in the employ of the firm for that length of time, the indemnity of his dependents is placed at one hundred and fifty six times the weekly wage. If the workman leaves no dependents, the employer is responsible only for his funeral expenses which are less than fifty dollars. This law has a tendency to place a premium upon men unencumbered by family ties, though it is a dangerous policy to hire young and inefficient men to positions requiring skill and general efficiency. The laws in this country are easy for the employer as he usually manages to blame all accidents to some workman and under cover of such irresponsibility for workman, he escapes.

The employment slip which the men must sign before they are allowed to go to work in the steel mills is a carefully worded little document and serves incidentally as a release to the company in case of accident resulting in injury or death to the signer. The steel mill workers say that because of this release, the steel company does not seem to care whether its men are married or without dependents. Others say that to the management the ideal worker is a strong, docile, willing, unencumbered man who will remain inside the mill fence, in case of a strike and be satisfied to work for months if need be as a scab, with the strikebreaker’s restaurant to furnish him with food and drink and the improvised dives to furnish him with entertainment. There are houses filled with cots and every preparation is made for keeping hundreds of men inside the mill yards in case of trouble with the men.

After each “heat” has been drawn from the blast furnace, the slag and refuse must be cleared out before a new charge can be made which is done about every seven hours. To clear the furnaces dynamite is sometimes used for blasting and it is dangerous business because the place is hot. In order to avoid any responsibility for accidents the steel company lets out this blasting to a contractor. He hires the men and if they are hurt, they are pretty sure to find themselves dealing with a poor man. However the steel company take them into the hospital at the mills. This is simply a “bit of generosity” on the part of the company.

Agents for accident insurance companies are given the freedom of the plants and allowed to ply their trade in all languages among the men. If a man says that he can not afford the extortionate premiums asked he is made to feel the displeasure of the company. If he is insured and is injured he can not collect his insurance money from the independent companies, until he has signed a release clearing the steel company from all responsibility for the accident.

The first man on the ground after an accident is the company photographer. He takes photographs from all sides and if any fatalities have occurred, the victims are taken as they died. The photographer makes the preliminary examination of witnesses and tells them to be in readiness to be called to the department of safety to make a statement. This department is nominally to protect the workingman but it is more truly used to insure the company against damages.

A workman was called to the department of safety to make a statement in regard to several men who had been killed. He was told to come next day to sign his statement which would then be in typewriting. On reading it over carefully next morning he found that two pages had been added and that it weakened, and in some points contradicted his story.

He refused to sign this doctored report and was leaving the room when the clerk told him to throw out the objectionable portions. Then he signed.

This man was an intelligent American and an eye-witness to the accident but he was not summoned to the coroner’s jury. The verdict from that body, was “From testimony presented, we the jury, are unable to determine the cause of said explosion.” They had called in a few frightened Hungarians who had to give their statements through an interpreter and who for the most part, stood blinking and shrugging their shoulders afraid of doing anything which would make them lose their precious jobs.

For ten years the good ladies of Homestead, Pa. have been trying to raise a fund for the purpose of building a hospital for injured steelworkers by giving straw-berry socials, fairs, etc. They insist in their kindness of heart that it is cruel to rattle the injured and dying men from fifteen to twenty miles to Pittsburg or McKeesport to the public hospitals.

But hospitals cost much money and Andrew Carnegie with his mind set on books and on the stars which young men should hitch to their wagons; Carnegie, who has reduced absentee management to a fine art; who is not within hearing of the shrieks of pain which sometimes come from the ambulances; this Mr. Carnegie has offered not a cent toward efficient hospital service in the mill-towns. The mills pay one dollar per day for each patient cared for at the public hospitals. This does not pay the cost of caring for injured and so the state of Pennsylvania makes up the difference from the taxes of the people.

In South Chicago, the Steel Mills have established a small, well equipped hospital within the Mill enclosure near the 89th Street gate. With the slum street on the outside of the wall and the constant roar of passing trains, stationary engines, whistles, the booming of blasts in the furnaces; all the roar of this intensive plant of production about them, the victims of industry lie in their beds, trying to get well.

Sanitary conditions seem to be better here, however. An electric magnet stands in readiness to attract metals from wounds. This is of great value to the unfortunate man with metal in his anatomy which went in hot and in a hurry and then had plenty of time to get cool, searing his flesh. The magnet pulls out bits of metal which no surgeon would be able to trace. Like a good shepherd the little magnet point, calls its own with its mysterious force, “and they know his voice and come.”

A pathetic incident is told by the women of the neighborhood. A young American of Polish parentage was killed one morning and taken to the hospital morgue. When his young wife came with his dinner to wait for him at the gate, the keeper asked her husbands work-number. it was the number of the man who had been killed. He was dismayed to face the situation before him. There stood the young woman bright and expectant, smiling in anticipation of the chat she would have with her husband as he ate the hot dinner she had brought in her basket. Soon the look in her eyes grew wistful-—his dinner was getting cold; so afraid were the men of the scene, it is said, that they let her wait for hours before the truth of her widowhood was finally told her.

The following accident is another typical one and illustrates what happens behind the steel mill enclosure. The converter bottom was blown away in one of the plants and the fifteen tons of metal, three thousand two hundred degrees hot, made a hell of the black depths of the building.

When the foreman had picked himself up and found that his injury was only two dislocated ribs, he turned to the dead and the dying. Two men were writhing in the most horrible torture and several with fearful burns were moving about. After the dying had been sent out on stretchers and the wounded sent away to walk to the hospital with a fellow workman, the foreman turned to the glowing heaving mass of metal on the ground. One of the Slag-men stepped up to him and whispered, pointing to the metal, “Mike’s in there!”

“Which Mike?” asked the foreman.

“Mike, the slag-man.”

The foreman convinced himself that there was certainly no Mike in the slag-man-crew who worked at the base of the converter.

The company’s record of the two men who died in the hospital that day, was as follows:

Name-John Knezovitch. Address–Strand Street. Occupation-Vessel Stagman. Injuries sustained. Severely burned on body, head, legs and arms. Caused by No. 3 bottom blowing off.

Name-Daniel Reploch. Address? Occupation-Vessel Stagman. Injuries sustained. Severely burned on body, head, legs and arms. Caused by No. 3 bottom blowing off.

The coroner’s record, dated nine days after the accident, was as follows:

“Milo Knezovich, now lying dead at 8749 Commercial Avenue, (undertaking establishment) said city of Chicago, came to his death on the 30th day of April, 1900, at the Illinois Steel Company’s hospital from shock of burns received from being caught in a mass of molten metal which fell from a vessel above him in the converting department in the Illinois Steel Company’s plant on April 30th, 1900, after an explosion is said vessel on above date. From the testimony presented, we, the jury, are unable to determine the cause of said explosion.”

The case of the other inquest was exactly like the above, only that the name given by the company, as Daniel Reploch was recorded by the coroner as Thomas Joran, with the same report as above and the same witnesses and jury.

The Hungarian who insisted that Mike “was in there,” was unfortunate. His fellows said that he talked too much. He lost his job.

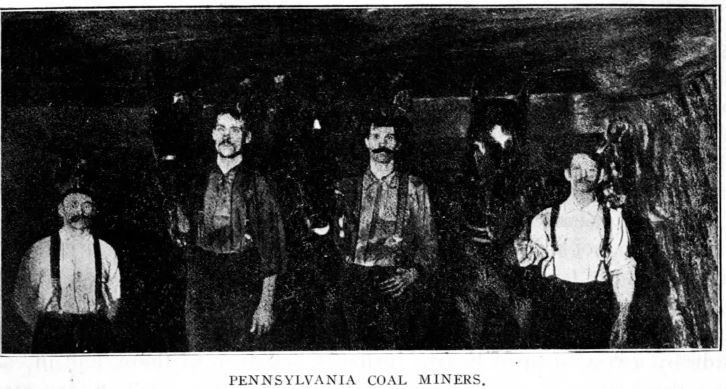

“Those fellows shifting along as if they could hardly walk another step, are blast furnace men,” remarked an old workman, as we watched the men leaving the mills after work. “I can spot a furnace man every time. They work a twelve hour day for less than two dollars an¢ on each alternate Sunday, they work a straight twenty-four hours without stopping. That gives them a whole Sunday off every two weeks. There are only three other kinds of work worse than this the lead workers, the sugar refineries, and the fertilizer works in Packingtown! It’s all hell to the unfortunate man who is so placed as to have only such work to keep him from starvation.”

In all the departments where the hot iron is handled many men succumb to the heat and are often carried out by their fellows gasping for breath. Perspiration must flow in streams from their faces and it must keep their heavy double woolen shirts soaked, to save the men from “keeling over.” They wear the thickest woolen shirts to be had in the market, even in summer as a protection from flying sparks. Wool smothers fire, where cotton or linen would burn.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v10n12-jun-1910-ISR-gog-EP-f-cov.pdf