A speech by Vincent St. John, General Secretary-Treasurer of the I.W.W. to a protest meeting in Chicago for the victims of the ‘Wheatland Riot’ describing the events in the strike of California hop pickers on the massive Durst Brothers farm.

‘The Wheatland Victims’ by Vincent St. John from Solidarity. Vol. 4 No. 40. October 11, 1913.

(Talk delivered at a protest meeting at 180 West Washington street, Chicago, Sept. 28, 1913, in behalf of the Wheatland hop pickers now confined in the Sacramento jail.)

Fellow Workers:

The occasion that brings us together here this evening is not by any means a rare one in the annals of the labor movement, especially in the last few years. Those of you who have followed the trend of events in the labor movement in this country the last ten or fifteen years no doubt have been struck with the ever recurring frequency you have been called upon to meet and to raise your voices in protest against some fresh act of oppression on the part of the employing class of this country. In a great many of these instances where you are called upon to show your solidarity the central figures in the case have been men and women of prominence, prominent by reason of their position in the labor movement, and because of that prominence they have enlisted more hearty support in their defense than those who have been less fortunate in their position in the labor movement.

The case of the fellow workers in whose interest we are here tonight is one where none of them has any prominence. They are simply members of the working class, unknown and unnamed, nine in number, who, in their struggle for existence, sold themselves for the time being as hop pickers to the owners of the Durst ranch at Wheatland, California. This ranch comprises some three or four hundred acres; the crop raised upon it consists wholly of hops and requires the labor power of some 1,500 to 2,500 workers to harvest, in the time allowed.

Durst Brothers don’t raise hops for the fun of seeing the vines twine around the poles and weave their way over the strings from one pole to another. They raise hops because they sell those hops at a profit. The amount of the profit which accrues to them in the cultivation and growing of their hops is measured by how cheaply they can secure the necessary labor power to cultivate the crop, pick it and get it on the market. As a consequence, when they have those 2,500 workers collected on that ranch they not only figure to work them for as small a wage as possible–paying them by the box, paying them by the number of boxes of hops they can pick from sunrise until it gets too dark to see to work–but they also figure various schemes by which they can tax these workers and take back from them the greater portion, if possible, of the amount that accrues to them for the expenditure of their labor power in those hop fields.

Now it happened that the men and women engaged in harvesting this last crop of hops on the Durst Brothers’ ranch had among their number members of the working class who had been delving into the subject of their own interest, who had been delving into the labor question, and through such investigation had arrived at the point of striving to bring together the individuals employed in the industry in which they were working, to bring them together for a common purpose.

When this season’s crop was being harvested the workers, as in past years, complained of the conditions under which they had to work. There were no housing facilities provided for them. They had to provide their own blankets. They had to sleep where they could find a place to spread those blankets. They had to build for themselves lean-to’s out of brush or camp on the opposite from the windy side of the haystack, or else they had to bring along with them their tents or make tents by going out and stealing, picking up gunny-sacks and burlaps, putting them together and making some kind of a shelter for themselves. The Durst Bros. who profited by using the labor power of these 2,500 men and women, were not concerned whether the latter had a roof over their heads where they labored, or not. They were not concerned whether they got good food to eat. Durst Brothers maintain a commissary and every worker in those hop fields was supposed to buy his supplies from this commissary at whatever price Durst Bros. chose to charge for the same. And you may be sure the provisions were sold at the highest possible prices, while being the very cheapest the bosses could find on the market.

In that portion of California water is not as plentiful as in some other parts of the country. They have to bore artesian wells; but the workers were not allowed to get water from these wells, for the simple reason that Durst Brothers had another scheme whereby they took from these workers some part of the paltry wage received as hop pickers. The owners had a cart conveying acid lemonade, a mixture of acetic acid and ditch water, with a little sugar or some sweetening compound. Working in the hop fields under the broiling sun induces a fierce thirst. These workers had to satisfy their thirst, and Durst Bros. compelled them to purchase this “mineral” lemonade from their cart at five cents per glass. The bosses would not allow them to pack a canteen of water into the fields with them to their work. They said: “You either go through the day here struggling to make a few pennies for yourselves picking hops, suffering from thirst, or else buy some of our especially prepared mineral water lemonade.” They did not provide any facilities to enable the men and women to attend to the calls of nature without stepping over the bounds of modesty and shame. These are but a few of the grievances that resulted in bringing together the men and women working in those fields. So they held a meeting and while this meeting was in progress, while speakers from their own ranks, members of the working class employed in those hop fields were voicing the grievances of themselves and their fellow workers, the Durst Brothers sent to the village of Wheatland and had an arm of the law to appear on the scene in the shape of a village constable. They had spotted some individual worker who, by reason of his activity had become marked, had made himself marked to them. They thought if they arrested this individual and took him off the hop field and had some one of their subservient justices of the village sentence him to the bastile for 30 or 60 days that would have a salutary effect upon the rest of those slaves in their employ. The constable came out there, without a warrant, without a writ of any kind and attempted to arrest one member of the working class, the one upon whom Durst Bros., in their ignorance, imagined all the agitation was depending. But the other workers refused to allow this constable to arrest their fellow worker. [Unreadable] away from the constable. They said: “You have no warrant, you have no right, and we will not permit you to interfere with this man’s liberty.” So they took him away from the constable. One of the women working in the field, in her excitement, slapped the constable in the face and he went down the road a sadder but somewhat wiser man. The workers continued their meeting.

They had erected a little stand in order that the speaker might be able to reach all of those 2,500 workers and, while the meeting was in progress, Durst Brothers were busy with their telephone. They called up the county officials, exaggerating the occurrence that had just taken place; and the officials of that county, the sheriff and district attorney, county clerk, and others who were situated in handy call from the court house, being used to riding rough shod over the workers of that locality in the past, summoned their automobile, piled into it to the number of eight or ten, and rode out to the Durst ranch. They drove up to within a few feet of the speakers’ stand and then, in the name of the law–that law which these workers have been told and which we have all been told is one and the same for rich and poor; that law which is supposed to spread its sheltering wings over the humblest inhabitant of the country–these emissaries of the law arose in their “majesty” and ignorance and commanded these workers to disperse. In order to emphasize their commands, they discharged a fire-arm in the air. The discharge of this gun, of course, created commotion, because these workers were like the average member of the working class, peaceably inclined, they were too peaceable. They were so peaceably inclined that they were not prepared to be anything else but peaceable, and were there like a band of sheep in a corral and without a gun.

The report of the gun emphasized the commands of the employers’ emissaries; the workers started to stampede in different directions, and the stand was torn down. But all the workers were not in that frame of mind. A few of them were differently disposed, and pushed their way to the front in order to argue with these emissaries of the law, in order to contest the point with them. In this counter-commotion these emissaries of the law, these brave gentlemen armed with shot guns, rifles and revolvers, lost their nerve and started shooting into this crowd of 2,500 defenseless workingmen and women. Whereupon a few active members of the working class, among whom was a native of the West Indies, worked their way through the crowd, threw themselves upon these fellows, wrenched their guns out of their hands and turned their own guns upon the sheriff and district attorney. And with such good effect that when the smoke of battle cleared, the district attorney had gone to his reward as well as the sheriff and one of the deputies (loud applause) and a few, some four members of the working class had also laid down their burdens of this life, had ceased to be wage slaves. As soon as these fighting members, one of whom was the West Indian worker (who was killed in his effort to protect himself and his fellow workers), succeeded in gaining possession of the fire-arms from the posse, that posse put on the full power of their automobile and speeded down the road back to whence they had come.

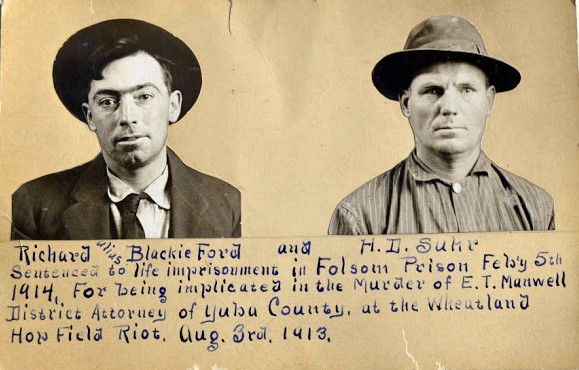

Of, course, they wired the governor, and he responded by sending in two companies of militia, who threw a cordon around the ranch and commenced to pick out members, the men who had made themselves conspicuous either in the battle which had taken place or in the agitation preceding the battles rounded up nine of them, and nine members of the working class today lie in the jail at Wheatland. California, awaiting their trial. Whether they are made victims to satisfy the demand for revenge, for vengeance and blood profit of Durst Brothers and the employing class of California, or whether they are permitted to go forth free men to again take up their labors in the struggle for working class freedom, depends entirely upon you and me and upon every member of the working class in this country. The purpose of this meeting is to try to impress that responsibility upon those present here today.

The purpose of this meeting is to give evidence of that feeling of solidarity that will make it impossible for the members of the employing class to victimize any worker, regardless of how little known he may be, regardless of whether he is prominent or not in the labor movement, regardless of who or what he may be. We want to bring about a solidarity that will respond to the needs of every occasion; that will prevent oppression and take from the clutches of the employing class every member of the working class whose life and liberty may be in danger. Regardless of what the charge may be against them, regardless of what excuse may be offered, regardless of what the expense is to you or to me, we want to have that solidarity at such a point that the members of the employing class will know that if they lay the finger of the law upon the humblest member of our class that solidarity will respond just as effectively and with just as much resources behind it as if they touched the highest among our number. (Applause.)

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1913/v04n40-w196-oct-11-1913-solidarity.pdf