H.W.L. Dana, radical scholar of Russian literature, with an essay on the life and work of the great Russian writer Maxim Gorki, who had such a profound impact on generations of rebels, on his death in 1936.

‘Maxim Gorki—Dramatist of the Lower Depths’ by H.W.L. Dana from New Theatre. Vol. 3 No. 8. August, 1936.

Maxim Gorki’s death has deprived us not only of a great champion of the toiling masses and a great realistic writer of stories about their lives, but also a powerful dramatist of some four- teen plays, the full value of which we are only just beginning to appreciate. The story of how Gorki, rising from the lower depths, first came in contact with the Moscow Art Theatre and turned dramatist, of his constant conflict with the Tsar’s dramatic censors, and of his final trilogy of plays written since the Russian Revolution is well worth examining in detail.

It was the spring of the century and the spring of the year–May, 1900–at Chekhov’s beautiful villa overlooking the blue waters of the bay at Yalta in the Crimea. The Moscow Art Theatre had just finished its second season, had already produced two of Chekhov’s plays, The Sea-Gull, from which it took its emblem and Uncle Vanya, and had come to Yalta to rehearse Chekhov’s new play, The Three Sisters. Since Chekhov could not go to Moscow, the Moscow Art Theatre had come to Chekhov. There in the congenial atmosphere of Chekhov’s home, were gathered together the gods of the theatre, Stanislavski and Nemirovich- Danchenko and their actors as well as various Russian writers of the day, Bunin, Kuprin, Chirikov and Chekhov himself–the flower of the Russian intelligentsia at the turn of the century, surrounded by the springtime luxuriance of the Russian Riviera.

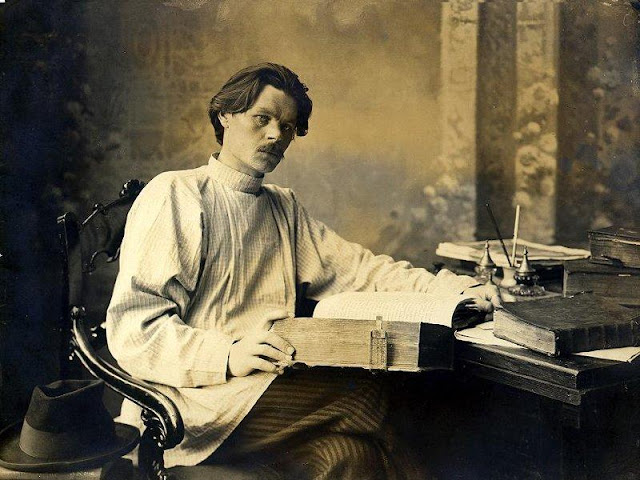

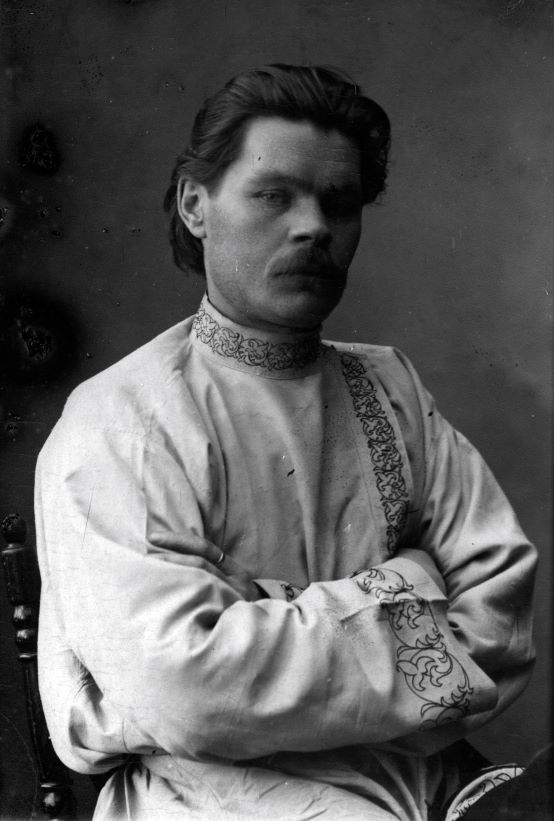

It was into this circle of well-dressed and polished intellectuals that there came a strange youth, dressed in a Russian peasant blouse. In his granite features they could see marks of the suffering and hardships he had already been through, but in his soft blue eyes they could also see the great compassion he felt for all who suffered. This was Alexei Maximo- vich Peshkov, former shoemaker’s apprentice, poor tailor, bake-shop worker and Volga stevedore, who had already been to prison several times for his revolutionary activities, and who had just made a name for himself as a powerful realistic writer of short stories under the name of Gorki, meaning “the bitter one.”

The leading actress of the Moscow Art Theatre, Olga Knipper, who was to become the wife of Chekhov the following year, said of Gorki’s coming: “He shot like a rocket into our quiet intelligentsia life and startled us with his accounts of a world unknown to us.” It was this unknown world that they wanted to know. As Gorki himself wrote: “I came from below, from the nethermost ground of life, where was naught but sludge and murk. I was the truthful voice of life, the harsh cry of those who still abode down there and who let me come up to bear witness to their hardship.”

Nemirovich-Danchenko with his aristocratic square beard, “the Grand Duke of the Moscow Art Theatre,” spoke of Gorki’s “searching impetuosity turned inward,” and felt “under Gorki’s calm exterior the store-house of power in reserve, ready to hurl itself forth.” It was this store-house that they wanted to tap. The Moscow Art Theatre had felt the need of new blood. In these years leading up to the Revolution of 1905, they wanted someone who could satisfy Stanislavski’s idea of a play expressing “discontent, protest, and the dream of a hero boldly speaking the truth.”

Chekhov had met Gorki the year before and, although troubled by his “lack of restraint and measure,” was deeply impressed by this stormy petrel of the Revolution. Chekhov said: “Gorki is a destroyer who must destroy all that deserves destruction. In this lies his whole strength and it is for this that life has called him.” Accordingly, Chekhov had invited Gorki to come to Yalta, meet the actors of the Moscow Art Theatre, writing: “Do come. Study the rehearsals and in five to eight days you will write a play!”

After the Moscow Art Theatre had gone, Gorki set feverishly to work writing plays. Chekhov bombarded him with letters: “Write! write! write!” Yet, instead of the “five to eight days” that the facile Chekhov had optimistically prophesied, Gorki worked for nearly two years on his first plays, The Lower Depths and Smug Citizens.

Meanwhile the file kept at Police headquarters under the heading of “A.M. Peshkov” was steadily increasing in size and the Moscow Art Theatre itself was at that time looked upon as too radical. It was thought that the censors might be less severe if they produced first a play dealing with the middle classes rather than with the proletariat. Accordingly they decided to open the season in their new Moscow theatre building with Smug Citizens. Yet even before that, while the Moscow Art Theatre was on tour, Smug Citizens was tried out at a private performance at the Mikhailovski Theatre in St. Petersburg. Gorki’s election to the Imperial Academy had just been annulled by the authorities and the police feared a demonstration of the indignant masses by way of protest. The neighborhood of the theatre was guarded by mounted Cossacks. As Stanislavski said, it looked more like the preparations for a general battle than for a general rehearsal.

The Tsarist censors who were present at this dress rehearsal insisted in cutting out from the play all passages in which there was any criticism of the social order of that time. The smug citizen himself, Bessemenov, was not allowed to say: “The times are troubled. Everything is cracking to pieces.” His rebellious son, Peter, was not allowed to say to his father: “Your truth is too narrow for us. It oppresses us. Your order of life is no use to us.” The poor drunkard, Teterev, was not allowed to say: “In Russia it is more comfortable to be a drunkard or a tramp than to be a sober and hard-working man. It is better to drink vodka than to drink the blood of people–especially since the blood of people today is thin and tasteless and all their healthy blood has been sucked out.”

It was above all, however, the grimy driver of a railroad engine, Nil, who terrified the censors as a prototype of the coming revolution. When Nil turns on the smug citizen, he was not allowed to say: “He who works is the master. Of course the Tsar’s censors cut out his culminating speech: “I and the other honest people are commanded by swine, by fools, by thieves. But they won’t be in power forever. They will disappear and vanish as abscesses disappear from a healthy body.”

Such were some of the passages which I found crossed out by the red pencil of the Tsar’s censor in the copy of Gorki’s Smug Citizens which I found still preserved in what was the Imperial Library of St. Petersburg.

Emasculated as the play was, the Moscow Art Theatre opened their new theatre with it on October 25th, 1902, and the play was acted in other cities throughout Russia as well as in Austria and Germany. But it is only since the Revolution that the play can be seen in its original form and with its true force. During the last year a splendid production has been put on at the Theatre of the Red Army, in which I found all these revolutionary passages that had previously been suppressed brought out with their full vigor.

While Smug Citizens was opening the season at the Moscow Art Theatre, they were already rehearsing a still greater play: The Lower Depths. Gorki came to Moscow to read to them the manuscript of his masterpiece. Chaliapin and Andreyev as well as the actors of the Art Theatre were there to listen spellbound to his reading. Kachalov, perhaps the greatest living actor of today, tells how Gorki read “beautifully” and how, when he came to the scene where the pilgrim, Luka, tries to console old Anna on her deathbed, the actors held their breath in stillness and Gorki’s own voice trembled and broke as he cried “The Devil take it!” and wiped away a tear with his finger, ashamed to let them see how much he was being affected by his own play.

Gorki’s reading produced a wonderful effect. The actors became enthusiastic at the idea of incarnating these “creatures that once were men. Olga Knipper Chekhova, who was to play the part of the prostitute, Nastya, got Gorki to show her just how a street-walker would make a “dog’s-paw” out of an old scrap of paper and roll tobacco into it to make a cigarette. Gorki “naively” offered to bring a street-walker to stay with the Chekhovs so that Madame Chekhov could “get a deeper insight into the psychology of an empty soul.”

Gorki did take Stanislavski and half a dozen of the other actors on an expedition at night to the Khitrov Market, where they wandered through the dark and gloomy cellars of Moscow into a labarynth of underground dens. Stanislavski gives a terrifying description of the rows of tired people, men and women, lying there on boards like corpses. When some of them were told the visitors intended to produce a play about people like them, they were so touched that they began to weep.

Before the play could be produced, the censors got busy. The head of the Chief Office of Printing Affairs, Professor Zverev (the name means “beastly”), cut out all the passages he thought dangerous. In the copy in the Imperial Library, I have found no less than fifty-four such passages cut out all together and many others modified:

Pepel was not allowed to say to the Baron: “You were a baron. There was a time when you didn’t look on us as human beings.” That would be disrespectful to the aristocracy. Kvashnya was not allowed to say: “I prayed to God for eight years and He did not help me.” Otherwise it might shake faith in the existence of God. The characters were not even allowed to say: “The peasants are tired of asking for bread,” or “It is impossible to live,” or “Prisons do not do anybody any good,” or “New times will produce new laws.” Stanislavski, acting the part of Satin, was not allowed to let his voice boom through the theatre, crying, “Truth is the god of the free man!” or “It is good to feel that you are a man! Man is something loftier than toil. Man is more than filling his belly.”

Yet even with all these challenging speeches cut out, there remained enough dynamite packed away in the play to produce a tremendous effect. When the first performance finally came on December 31st, the last day of that year, 1902, the realistic intensity with which the actors stressed their lines, spoken out of the darkness or The Lower Depths, was like hammering on dynamite. Never before or since has the Moscow Art Theatre had such a tremendous triumph. One enthusiast who was present wrote: “The old theatre had ceased to exist. The curtain rose and there appeared a new theatre. Life itself was poured onto the stage.”

When the final curtain descended, pandemonium broke loose. As Stanislavski says: “There were endless curtain calls for the actors, the stage directors, and for Gorki himself. It was very funny to see him appear for the first time on the stage and stand there with a cigarette in his mouth, smiling and lost, not knowing that he was supposed to take the cigarette out of his mouth and to bow to the audience.

The play became such a success at the Moscow Art, Theatre that the censors, who had allowed the play only because they were confident it would fail, now did not dare to stop it. They did, however, forbid its being acted by any other theatre in Russia. Yet the Moscow Art Theatre acted it wherever they went on tour. In Imperial St. Petersburg the Tsarist press attacked it fiercely. Some of the aristocratic critics there claimed that they were so disgusted by The Lower Depths that they had the sensation of being forcibly ducked into a sewer.

Yet this powerful play, like the great censored plays of Ibsen, Strindberg, Hauptmann and Shaw, made its triumph around the world. The very next year, Max Reinhardt produced his famous version in Berlin under the title of Nachtasyl which ran for 500 nights, though the Kaiser Wilhelm II consistently refused to see it. In New York it was produced under this same title in German at the Irving Place Theatre long before it was produced by Arthur Hopkins under the title of The Lower Depths, or by Leo Bulgakov in a colloquial new translation under the title At the Bottom. It has been translated into every language and only a few years after the Russian-Japanese War, was acted in Japan. Productions of The Lower Depths along with his more recent plays, would be a fitting tribute to Gorki in the year of his death.

Since the Russian Revolution, The Lower Depths had been acted more often in the Soviet Union than any other play by any living Russian author. Upon Gorki’s triumphant return to Moscow in 1928, I saw it acted for my seventh time; but this time in the presence of Gorki himself, with the majority of the original cast in their original roles-Stanislavski as Satin, Kachalov as the Baron, Moskvin as Luke, Vishnevski as the Tartar, Chekhov’s widow as Nastya, and so on-only now they were able to utter the full text freely and frankly and fully. There they were representing the derelicts of the old social order, gathered together in that underground den in the brown shadows under the dim irreligious light of the lamp. It was like some great painting of Rembrandt come to life. Out of the darkness I could hear the voices of the potential power of man even in the lower depths. Gorki’s powerful play, written at the beginning of this century, marked a pivotal point in the history of Russia. In The Lower Depths one can already hear the onward march of the Russian Revolution.

From the down-and-outs of The Lower Depths and the petty bourgeois of The Smug Citizens, Gorki now turned to a third stratum of Russian society–the intelligentsia. The more “Gorki, the new sensation” was lionized by the highbrows, the more biting he was in his satire of them.

In Summer Folk Gorki pictures a group of futile intellectuals gathered in a summer cottage and in contrast to their complacent self-conceit, a few of their number who, wishing to find a way out, decide to leave these summer folk and do something useful, to build schools and hospitals in the provinces. At the first performance in the Komisarzhevski Theatre in St. Petersburg on November 4th, 1904, most of the audience applauded when one of the rebellious characters, attacking the weakness of the intelligentsia, said: “You are not really intellectuals. You are just summer visitors in your own country, fussy people looking for your own personal comfort, doing nothing and talking disgustingly much. The working classes sent you ahead as intellectuals to find the best way out for them; but you have lost your own way and the workers now look on you as enemies who are living on their work.”

The truth of this attack on the intelligentsia met an immediate response from the sturdy common people; but the anemic intellectuals squirmed in their orchestra stalls, wincing under the attack, and at the end, tried to hiss the play. Gorki came before the footlights and vigorously hissed back at them. As he said afterwards: “I certainly out-hissed that bunch of highbrows!”

Within two months came the Revolution of 1905 and the Bloody Sunday of January 9th when the Tsar’s officers shot down hundreds of the workers in their peaceful procession before the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. Immediately Gorki was inflamed with fury at this outrage. On account of the violence of his protests, he was arrested and imprisoned in the Fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul. I have visited his cell there in that heroic prison, number 39 of the Trubetskoi Bastion. There it was that he wrote his next play, the tragicomedy The Children of the Sun.

In this play he represents a sensitive woman, Lisa, who has seen “the blood on the snow,” the shooting down of hundreds of men, women, and children in the streets. The result has been that she has suffered a nervous collapse in which she can no longer bear the sight of blood, and having seen so many deaths cannot bear the thought of death. Her brother, the chemist Propasov, enthusiastic about his scientific experiments, looks upon her and all who feel as she does as weaklings. In contrast to them, he sets up himself and the intellectuals who feel as he does as “children of the sun.” Yet in his idealism, he is powerless against grim reality and, in a riot, the indignant people rush on the stage and attack the intellectuals.

The play was produced both by Komisarzhevski in St. Petersburg and by the Moscow Art Theatre on the same day, October 21st, 1905. The Revolution of 1905 was still going on. It was during those tumultuous October days when the first general strike in history was taking place, when the Black Hundreds were carrying on the most terrible repressions and when there were horrible pogroms at Kiev and Tomsk. In Moscow the rumor spread that the Black Hundreds, looking on Gorki as a dangerous revolutionist, were going to attack the theatre during the first performance. Stanislavski gives a lively description of how, in the last act, when the mob climbed over the fence and attacked the intellectuals and a pistol shot was heard and Kachalov, who was acting the part of the scientist, was seen to fall, the audience thought the mob of supernummeraries was the Black Hundreds attacking the actors, and cried out: “They have killed Kachalov!” “Revolvers suddenly appeared in the hands of most of the spectators. Many women fainted, others had hysterical fits, the couches in the foyers were covered with their bodies.” So says Stanislavski with pardonable exaggeration.

During this same year, 1905, Gorki wrote another play called The Barbarians, representing a group of engineers coming into a district town on the shore of a river, finding the primitive life of the common people there, and bringing into those simple surroundings the degeneracy of the big city from which they have come. The play was planned for the Mos- cow Art Theatre, but was never produced.

A far more important play was written in the following year, 1906, called Enemies. Here Gorki clearly envisaged for the first time the class conflict and represents the two classes, the workers and the owners, as inevitably “enemies.” Gorki does not deny that the owner may be a good man. Indeed, he represents Bardin and his family in a very sympathetic way. But as they sit there in their charming garden, we hear the hum of the factory over the fence and we know that the conflict is latent in the system itself. As one of the workers says: “The owner may be a good man, but his goodness does not help us any.” In a conflict in the factory, Bardin’s partner, a harsh and unjust man, is killed and the class war is on. The capitalists call in the police to help them, to which the workers say: “You depend upon the police; but we depend upon ourselves.” When, finally, soldiers as well as police have been called in to protect the factory owners, Bardin’s niece turns on the owners and says: “Soldiers can’t protect you from your own stupidity.” When the stern prosecutor, the brother of the murdered factory owner, wishing to put the girl in her place, tells her; “Laws are defied only by children and revolutionists,” she replies boldly, “Then I’m a revolutionist!” At another point Gorki inserts the dangerously pregnant remark: “If you begin to ask yourself questions you will become a revolutionist.” When the workers are led off to prison and execution, Tatyana, seeing their fine spirit of solidarity, cries: “These people will conquer in the end.”

The censor, in this case, realized that it would not be enough to strike out certain passages as he had in Smug Citizens or The Lower Depths. He prohibited the entire play. Unlike Anglo-Saxon censors, he was perfectly frank in giving his reasons. They are worth quoting in full: “Because the play stresses sharply the terrific enmity between workers and employers, be- cause it represents the workers as stoical fighters going consciously toward their goal–the abolition of capital, because it represents the employers as narrow egotists and, regardless of their personal characters, enemies of the workers, because Tatyana predicts the ultimate victory of the working class, and because the whole play preaches against the possessing class, therefore Gorki’s Enemies cannot be permitted to be performed.”

Accordingly, Enemies, so far as I know, was never acted before the Revolution. Since the Revolution, however, I have seen it done at the great Alexanderinski Theatre in Leningrad, at the Maly Theatre in Moscow, and within the last year, the marvelous new production at the Moscow Art Theatre.

In his experiences during the Revolution of 1905, Gorki had plenty of opportunities to see the brutality of the Russian policemen. In most of his plays he had taken random shots at the police. Now he devoted a whole play to them in his next drama, The Last Ones, written in 1908. The censors came down on it like a ton of bricks. The prohibition of June 10th, 1908 is again quoting in full: “Why it is called The Last Ones, we have no idea. The author represents the police as rogues. He touches the burning question of the relations of the police to civilians. Because of this, the performance of this play in a theatre might provoke the sympathy of a part of the audience. Accordingly, we think it necessary to prohibit the above-mentioned play.”

In 1906 Gorki left Russia and came to the United States with the actress Andreyeva, hoping to get help for the Russian revolutionists. At first he was dined and wined, sitting at a banquet between Mark Twain and Arthur Brisbane. But when it was discovered that Gorki had sent sympathetic telegrams to miners on strike and to Bill Haywood in prison and when the Tsar’s Embassy sent statements to the American newspapers that Gorki was a dangerous radical, the Arthur Brisbanes dropped Gorki like a red hot poker and moral America found a moral pretext for inhospitality towards the Russian revolutionist, driving him out from hotel to hotel.

Disgusted with New York, “The City of the Yellow Demon” as he called it, Gorki returned to Russia and started writing several new plays attacking bourgeois society. It was the period of disillusion, hopelessness and terror following the failure of the Revolution of 1905, and the plays of Gorki published in 1910 are full of bitterness against the corruption of that period.

In Odd People Gorki unmasks a group of hypocrites. In Vassa Zheleznova Gorki gives a terrible picture of a ruthless mother, dominating her family by the power of money, making her dying husband sign a false will, causing her daughter unnecessary anguish, and forcing her crippled son to go against his will to a monastery. Children, a one-act play, The Zykovs, and The False Coin, written in this intermediary period, between the two revolutions have little value today except for Gorki’s scorching satire on the conditions in Tsarist Russia at that time.

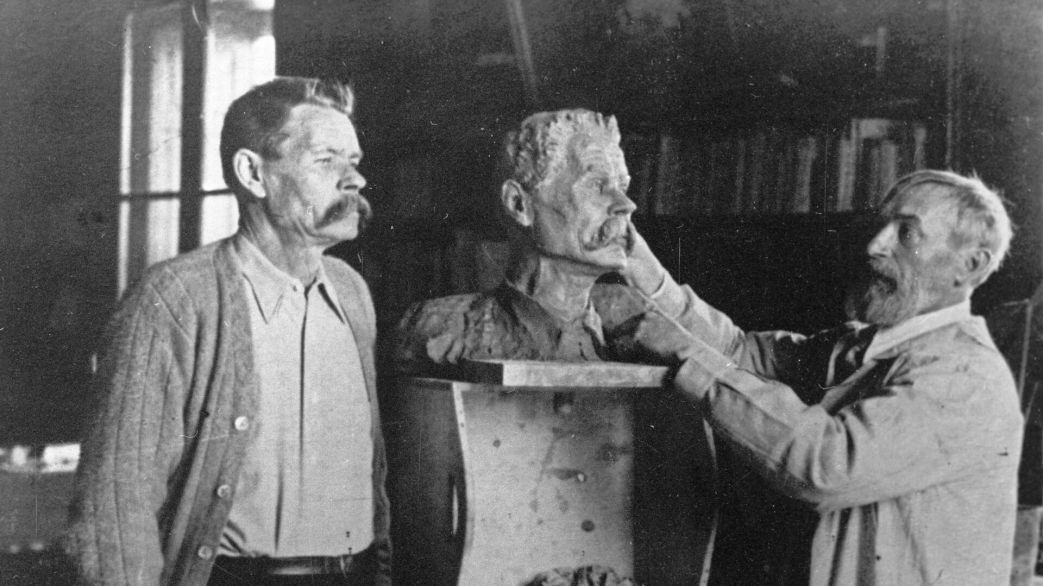

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was hailed by Gorki as “the sunniest and greatest of all revolutions.” His differences with Lenin were quickly reconciled and under Lenin’s strong influence, Gorki became enthusiastic about this new social order which was placing science ahead of superstition and liberating the working masses, whose cause Gorki had so long pleaded. Except for The Judge, a play written in 1918 about an old man who hunts down a former prison companion who has become successful and powerful, and whom he accordingly hates, it was a dozen years or more before Gorki turned dramatist. The great drama of the early years of the Revolution and of the war against invasion, Gorki’s breakdown in health from the tuberculosis which he had first contracted in Tsarist prisons, his years of recuperation in a sanatorium near Berlin and at Sorrento in Italy at Lenin’s advice, his triumphal return to Moscow in 1928, and his absorption in the wonderful new socialist upbuilding which he found there-all this had left Gorki little opportunity for producing plays. With the coming of 1932, however, and the celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the beginning of Gorki’s literary career, he announced a trilogy of plays-unfortunately left unfinished.

The first part, Egor Bulychev and Others was first performed on September 25th, 1932, on the occasion of this anniversary, at the Vakhtangov Theatre in Moscow, in the presence of Gorki himself, Henry Barbusse, and other writers who had come there to do him honor. I shall never forget the excitement of that opening night. Later it was produced at the big dramatic theatre in Leningrad and still later at the Moscow Art Theatre itself.

In this play Gorki represents a bourgeois capitalist, Egor Bulychev, on the eve of the Russian Revolution. Egor is slowly dying of cancer. During the four acts of the play he declines more and more till we come to his death at the end. At the same time during these four acts the revolution is rising more and more until it breaks out triumphantly at the end. Such is the general pattern of the play. Egor distrusts the coming revolution. He feels it will destroy the two most precious things in the world: religion and the family. Yet Gorki shows up mercilessly how little sacred either of these was in this case. The priest, who has been sponging off Egor all these years, is waiting for him to die, in hopes of a big bequest in his will; while the nun, the sister of Egor’s wife, quarrels with the priest, hoping to get the bequest for herself. Such is the sacredness of the religion which Egor felt was threatened by the Revolution. As for the family, the quarreling of the daughters, the intrigues of the son-in-law, Egor’s illegitimate daughter, and his affairs with the maid servant show up the sham of what he calls the sacredness of the family. All sorts of devices are used to try and save Egor. A woman mind-healer is brought in, a crazy peasant-healer like Rasputin, and finally a trombone player, who tries to persuade him that by playing on the trombone loud enough, he can get all the bad air out of his system. The name of the trombone player proves to be Gabriel and the neighbors rushing in think it must be the Angel of the Last Judgment blowing on his trumpet. The laughter that inevitably greets this scene shows that the mature Gorki, now that the Revolution was well established, could make hearty fun of the old order and was capable of great comedy as well as of great tragedy.

The second part of the trilogy, Dostigaev and Others represents Egor’s foxy business partner, who was able to survive the Revolution and flourish as a Nepman for a time. It was first produced at the Vakhtangov Theatre in Moscow, on November 25, 1933, and like the first part of the trilogy has been acted in New York in Yiddish at the Artef. But not yet in English.

In addition to the works which Gorki himself wrote in the form of plays, there is an almost endless number of his novels and stories which have been dramatized by others. I have myself seen dramatizations of Chelkash, The Orlof Couple, Malva, Kain and Artem, Foma Gordieyev, Three Men, Mother, and In the World. Mother, in addition to other dramatic versions, has been astoundingly presented by Okhlopkov at the Realistic Theatre, where he presents the play on a circular stage in the very midst of the audience. In the World, representing scenes from Gorki’s own life, has been most beautifully done by the Moscow Art Theatre itself.

These same stories and others have been turned into moving pictures for the screen. These film versions especially Pudovkin’s remarkable film of Mother as well as the stage versions show how dramatic Gorki’s work really was, even when he was not consciously writing drama.

In the last analysis, however, the greatest of all the dramas of this dramatist of the lower depths is neither his plays nor his dramatized and filmed stories, but the drama of his own life. This is the great drama of a writer emerging from the lowest depths and rising through the class struggle to heights where millions of men look up to him with a devotion that they feel to no other author.

As part of the great celebration in Gorki’s honor in 1932, it was announced that two of the greatest theatres in the Soviet Union-the Moscow Art Theatre and the Big Dramatic Theatre in Leningrad-were to be called “in the name of Gorki.” I shall never forget Gorki’s embarrassment and his gesture of spreading his hands apart as though depreciating an honor which he felt he had not deserved.

Gorki modestly muttered: “I wrote plays because I had to. That is why they are SO bad. But if I had studied the theory of drama they would have been much worse!” Yet Gorki’s characteristic bit of Russian self-criticism should not blind us to the fact that his Lower Depths has been more popular and stirred people more deeply than any play by a contemporary writer, that if Gorki’s other plays were not quite so successful it was largely because the Tsar’s censors had cut out the most vital passages, and that his series of fourteen plays, as they are now being revived in their full form, prove, by their rugged and realistic dramatization of life, that they rank among the most powerful plays of social protest in world drama.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v3n08-aug-1936-New-Theatre.pdf