Milwaukee’s Socialist history is largely seen from its ‘sewer socialist’ municipal governments of the 1910-30s, however its story goes back much further. Here, a veteran of the movement gives an early history of the Socialist Movement in ‘Cream City,’ from the first German papers in the 1870s, through the establishment of the Socialist Labor Party, and the rise of Victor Berger.

‘Socialist Reminiscences of Milwaukee’ by H. Bottema from the Weekly People. Vol. 17. Nos. 8 & 9. May 18 & 25, 1907.

(We are greatly indebted to R. Wilke, senior, for part of the information contained in this article. H.B.)

The Socialist movement in Wisconsin began prior to 1870, when, in the city of Milwaukee, there existed at that time a branch of the “International.” However, the correct time of its incipiency, its influence among the workers of Milwaukee and throughout the State of Wisconsin, the years of its existence are, for lack of proofs, a closed book; at least I have tried hard to gather material of the “International” in Milwaukee at about the year 1870, but my attempts were in vain, as far as to gaining a minute description of the then working movement in the Cream City is concerned.

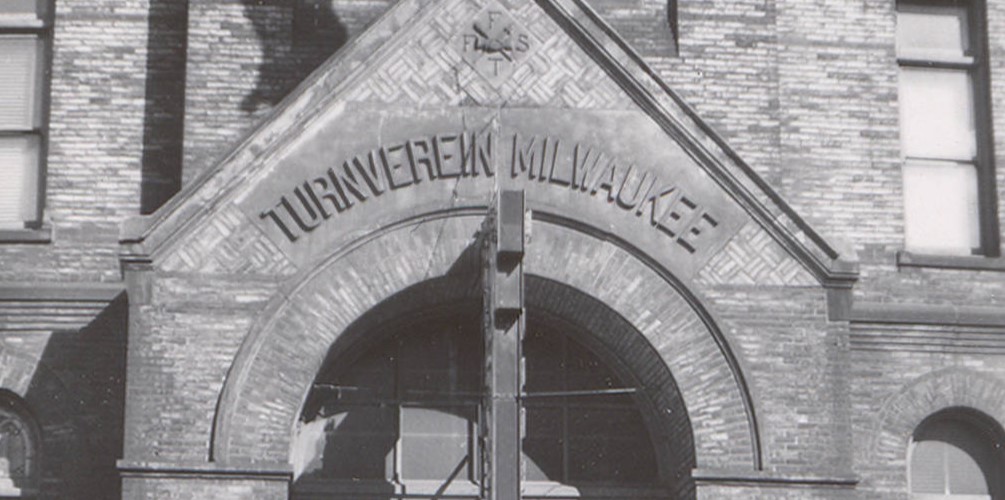

In the year 1875, the labor movement, the socialist stream, seems to have gained a strong foothold in the metropolis of the Badger State. An old minute book, still in the possession of Section Milwaukee, is an eloquent witness of the socialist movement in Milwaukee at A.D. 1875. The movement, as the minute book indicates, was dominated by Germans, for the minutes are written in the German language and also the name “Social Politischen Arbeiter Verein zu Milwaukee,” shows that the German “Genossen” were the predominating factor in Wisconsin’s early socialist labor movement. They were the pioneers–pioneers for a new system, for a higher civilization.

The German comrades issued a local paper called “Der Socialist.” The paper ceased publication in 1880.

John Nusser was at that time secretary of the “Social Politischen Arbeiter Verein” of Milwaukee; these also have served in the same capacity for the society: F. Oscar Linche, Herman Zweek, Jos. Brucker, David Kleinman, Wm. Schniett, H. Matthey, Oscar Huie, Henry Hoffman, Gustav Lyser, E.A. Raenber, Wilhelm Wetzel and W. Predans. Siegel, Brucker and Lyser seemed to have played an important part in the movement of those days. The first-named person, as will be remembered, went over to the camp of the enemy. He afterward deserted the socialist movement and became identified with “Abendpost,” a German Republican daily. He was its editor for many years, till his death. It is claimed by older comrades that this erstwhile socialist, in the paper he edited, hurled his shafts of destruction against socialism, but, of course, to no avail.

There was a retrocession in the socialist activity in the organization and propaganda carried on. But about 1880 the local movement gained many recruits from German immigrants. It was a mighty impulse given the then socialist movement by the sturdy sons of far-away Germany, who, trained in the school of experience, many of them no doubt actually having faced squalor and want, made good timber; at least for those days.

The movement then became known as the “Social Democratischen Verein von Milwaukee.” Later on, when Michael Biron became active in the Socialist labor movement of Wisconsin it was surnamed “Social Democratischer Partei.” There was great activity displayed about the year 1880; as said, the movement here got a new impetus, more strength and energy from German immigrants.

Michael Biron, who played a prominent part in Wisconsin’s labor uprising, was formerly a priest. He, however, became thoroughly convinced of the hypocrisy of the Roman Catholic faith, renounced his former belief, became a freethinker and socialist, at least, he has been active in the labor movement in Wisconsin. He founded the “Volksblatt,” a daily paper. He was its owner, its editor and put in his spare time in helping to set type. The place or office where the paper was printed was on Oneida street, between River and East Water streets. At the present time, this site, where once flourished the first Socialist daily of this State, is occupied by the Pabst Theatre, the well-known German playhouse.

Biron had not much room in his office, although he also lived there, besides issuing from the same rooms his daily “Volksblatt.” Not the whole paper was printed there. The paper printed on the inside was sent him from Chicago. He then wrote the editorials and other local matter. Once during a snowstorm which was raging for several days his paper did not arrive from Chicago; that was very inconvenient, at least the good people of Milwaukee did not know that the “Volksblatt” was dependent on Chicago for support. Such days were trying moments for the owner, editor and compositor of the “Volksblatt.” The newsboys could not cry out their wares and the subscribers were deprived of their daily literary friend and companion. As the “Volksblatt” was being morally and also financially supported by the socialist organization of Milwaukee, it ought to have sustained the principles and tactics of the section, which it did not do. Finally the breach between the “Volksblatt” and the Milwaukee Socialists became ever wider, so that no hand of comradeship could reach over the gulf, to kiss up and renew the bond of friendship. The Volksblatt, for lack of patronage, was at last compelled to discontinue publication.

During those days much agitation was carried on, but all in German, and the meetings were conducted mostly in small halls. Comrades Viereck and Fritsche, both members of the German Reichstag, were here in the city of Milwaukee on March 13, 1881, addressing a mass meeting at Freie Gemeinde Hall, on Fourth street. Fritsche, besides being a member of the German lower house, was also president of the tobacco workers’ union of Germany. Viereck seems to have been more a man like our present Social Democrats, i.e., trying to get something out of the labor movement. Both comrades had been sent to the States to secure financial aid, for these were still the days of the German anti-socialist laws. M. Schwab, the man whose name has become known throughout the whole civilized world in connection with the labor movement in Chicago and especially the meeting on Haymarket square in Chicago and the subsequent infamous trial, was at that time organizer for Section Milwaukee. The movement flourished in and around the years 1880 and 1881.

After M. Biron had suffered ship- wreck with his daily “Volksblatt” he founded “Lucifer,” a weekly paper devoted chiefly to the cause of free thought. With masterly hand did Biron deal the clergy blow after blow, his arrows of satire and ridicule at least must have annoyed the gentlemen of the cloth both in Austria and Germany, so much so that “Lucifer” was barred from the German and Austrian mail. But the ex-priest Biron did not give up hope of informing the people abroad to keep them posted on the views he held on “Christianity.” In order to do this he changed the title of his paper; thus “Lucifer” became “Arminia” and continued to enlighten, the people abroad. “Die Erlebnisse eines Katholischen pfarrer” (the events of a Catholic priest) were articles from his pen, keen, forceful and logical; which appeared in the “Lucifer” or “Arminia” and must have been an eyeopener to many pious people. The Socialist movement in Milwaukee regained control over “Arminia,” which later on became the “Milwaukee Arbeiter Zeitung.” The office of the paper was at that time on East Water street, between Wisconsin and Mason streets, on the west side of the street. Paul Grotkow, the well-known labor agitator, was the first editor from the time on Section Milwaukee acquire control over the paper (Arminia) and rebaptized it “Milwaukee Arbeiter Zeitung.”

Grotkow was a mason by trade, a man who was proficient at his profession. The beautiful mason work, those impressive windows, from an architectural point of view, which are to this very day to be seen in the front wall of Chapman’s dry goods store on Wisconsin street, are the work of Paul Grotkow.

The party was now better known as “Socialistische Partel von Nord Amerika” (Socialist Party of North America). Section Milwaukee was in a flourishing condition at that time. There were 86 good standing members, besides a great many friends and sympathizers who were lending their aid to make the movement strong. George Winters, of St. Louis, a cigarmaker by trade, was invited to Milwaukee to carry on the work of agitation and organization. Winters was able to speak both in English and German. He remained a few years with the Socialists of Milwaukee. A big strike of the cigarmakers broke out in 1882 which lasted for over half a year.

The party in 1882 took part in the election. V. Blatz was put up as alderman of the fifth ward. He was the only candidate on the ticket but was defeated by his opponents.

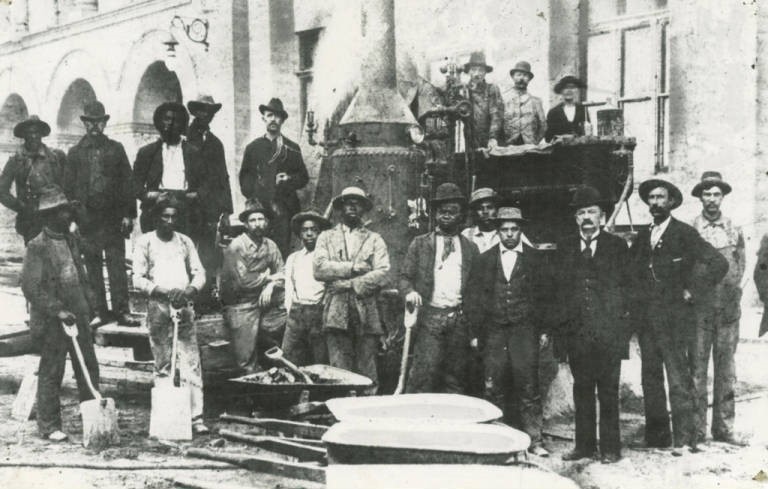

Between 1882 and 1886 there, was great activity displayed by the German Socialists of Milwaukee, especially in 1886, before the great strike broke out in Milwaukee as well as in Chicago. A gathering of workingmen, a peaceful meeting, held to discuss the strike situation was dispersed by the police and some workers were clubbed into insensibility. This happened in Milwaukee Garden, at the beginning of May, 1886. Milwaukee at that time was in a state of uproar. Soldiers could be seen everywhere. Those were trying days. strike was universal in Milwaukee; nobody worked or dared to work. The State militia had courage as all soldiers have, when facing disarmed citizens.

Down in Bay View, a procession of strikers was wending its way through the street of the southeast side of Milwaukee; a flag was carried by one of the strikers who marched in front. The commanding officer of the soldiers without convincing himself of the kind of flag the man carried, gave orders to shoot to kill. The command was obeyed and when the smoke had cleared itself from the scene of battle it was found that the standard bearer was mortally wounded; besides him, full of holes, was the flag he had carried–it was an American flag! If ever Old Glory was dragged through the mud, grossly insulted, then it was done by the soldiers–American soldiers at the Bay View rolling mills at that time.

Liebknecht visited Milwaukee in the winter between 1886-1887. A large meeting was addressed by him in Schlitz Park Hall. Liebknecht was touring the United States at that time and had a personal interview with the incarcerated labor leaders of Chicago in the Cook County jail.

That the old Socialist party was quite strong during and before ’86 can be seen from the fact that a complete city ticket was put up by the party under the name of “Union Labor Party.” The capitalist party sailed under the name. of “Citizens Party.” However, the “Union Labor Party” was beaten, but the fact that they were able to put up a whole ticket showed that there must have been something doing in those days.

After Paul Grotkow had left Milwaukee for Detroit and later had gone to California, M. Biron again gained control of the “Arbeiter Zeitung,” or rather served in the capacity of its editor. At that time the whole movement was in a chaos. The office of the “Arbeiter Zeitung” was later on removed to State street, between Sixth and Seventh streets, where it has remained for many years.

Thus Mr. Biron was once more actually engaged in the labor movement.

As said, the years following the big strike of 1886 brought about a stagnation in the labor world. It took a number of years to get over the setback. However, as a whole, the big strike of May, 1886, has been a good lesson for the working class; especially for those that understood so very little of the struggle between capital and labor, and notwithstanding their ignorance, wanted to pose as leaders. But gradually Father Time healed the wounds and the working class again gathered around the standard of organization with as much vigor, hope and aspiration as ever before. Hickler, at the present time connected with a capitalist German daily in Cleveland, Ohio, was for a short time the editor of the Arbeiter Zeitung. He was Mr. Biron’s predecessor. Mr. Hickler accepted a position as reporter on “Der Herald,” a Milwaukee German daily. He left the editorial chair of the Arbeiter Zeitung. Later on he became city editor on the same paper and at the present time is editor of a capitalist daily in Cleveland.

Again Mr. Biron became the editor of the Arbeiter Zeitung. The “Arbeiter Zeitung” at that time was still issued daily. The Socialists of Milwaukee were in those days a unit–a unit of solidarity of purpose. To illustrate what this oneness of purpose means, what it signifies in the labor movement, let us take the “Arbeiter Zeitung” as an example. When Mr. Berger sought to bring about the subjugation of the local Socialist organization and met his Waterloo, the Arbeiter Zeitung (Vorwarts) for lack of support, could not be issued daily any more. It became a weekly publication, as it is still up to this very day.

While we are at it, let us also state that the weekly issue of the “New Yorker Volkszeitung” gained hundreds of readers in Milwaukee and throughout the State, but when later on the “New Yorker Volkszeitung” showed its disloyalty to the Socialist Labor Party, it lost almost all its subscribers.

But to take up the thread of our reminiscences.

Victor L. Berger on January 1, 1893, took charge of the “Arbeiter Zeitung,” the name was changed to “Vorwarts.” This was the first entrance of Berger in the labor movement. He had been a school teacher, but did not seem to like to continue his profession and thus be- came editor of the “Arbeiter Zeitung.” There were two national Socialist movements at that time: the Cleveland and Brooklyn. Milwaukee was affiliated with the Brooklyn movement. Berger, as it seemed, wanted to do things on his own hook. At a meeting of Section. Milwaukee, held at its meeting place on Fourth street in the year 1893, it was in the early spring, if I remember well, that about 10 members declared that they would apply to the N.E.C. of the party (Brooklyn movement), for a new charter. It was then said that as a new man had gotten hold of the “Arbeiter Zeitung” it was time to form a new party. Of course the deserters did not get a charter, such a thing would have been unconstitutional. From that time on the split in the Milwaukee Socialist movement dates its origin. Mr. Berger and a small clique of men should be thanked for it. An “independent” group of Socialists headed by Berger, J. Doerfler and a few minor lights had been founded. But let us go back a few years in the history of the political and economic labor movement of Milwaukee and Wisconsin.

Robert Schilling had in the year 1886 founded in the State the then Knights of Labor–the economic movement. He also was a prominent figure in the Greenback party. His paper, “Reformer,” was printed on Market street, opposite the City Hall, and was half German and half English. Both the Knights of Labor and the Greenback party found in Robert Schilling a staunch supporter. When, however, later on, both the Knights of Labor and the Greenback party showed signs of decay the People’s Party was founded out of the remnants of those two movements. The people’s party elected Henry Smith, at present time Democratic alderman, to the United States Congress. Later on, when the People’s Party dwindled down to almost nothing, Mr. Berger, by organizing an independent group of Socialists, had plans all arranged to gather the scattered forces of the erstwhile flourishing People’s Party within its rank and to build up a large “Socialist” movement. In fact, he has succeeded fairly well in this; that is, in organizing the scattered forces of the old People’s Party. But the thing still lacks that revolutionary spirit without which any movement will sooner or later go to the dogs.

The first political activity of the group of Socialists of which Berger was the leader, took place at the election of 1894, when a so-called “Co-operative ticket” was put in the field. However, the enterprise was a miserable failure. It would take too long to go into detail about the political and economic movement of those days. At that time, our comrade, Minckley, who had lived a short time in Chicago, and had also been active there in the movement, found in the city of Milwaukee an interesting lot of reformers, of all colors of the rainbow. Minckley, being an able speaker and debater, besides having a clean understanding of the basic principles of socialism, has done much to clarify the atmosphere. Many will remember the debate which he held with Mr. Ulrich at Frei Gemeinde Hall. The co-operative stores and kindred institutions which were advocated by Ulrich, Smith and others were hurled in the air, were shown to be an absurdity, a thing long ago discarded; since Saint Simon, Fourier and Owen, the one more or less advocated reforms. It is as but yesterday–it seems to me so clearly I still see before me the faces of astonishment, after Minckley got through with his explanation of the only true revolutionary movement–the movement as laid down by Karl Marx.

The old movement (Socialist Labor Party) kept on to the straight road. Comrade R. Wilke, senior, was organizer of Section Milwaukee in the year 1896, when the Section entered the municipal campaign. The convention was held at Casino Hall, corner Seventh and State streets. Charles Pflueger was put up for Mayor, Fred Schuster for Treasurer and Jacob Rummel was our candidate for Comptroller. We got 450 votes at the first election. Berger and his in- dependent group did not that year, but two years later, again entered the political campaign. Robert Schilling and his People’s Party took part in the election of 1896, but polled only 6,689 votes. The Socialist Labor Party has since, at every election, put up a ticket. The English society, known as the Academy of Social Science, was founded in 1895, and has under the same name for a number of years carried on the good work of agitation and organization among the English speaking people. It used to meet regularly every Sunday evening at Hoppe’s Hall, Seventh and Walnut streets. It has accomplished much good. Later on the name was changed to “Young Men’s Socialist Club,’ at present better known as the English branch of Section Milwaukee of the Socialist Labor Party.

The “Kangaroo” disturbance did not do Section Milwaukee much harm. Jacob Rummel and a few others left the party, but otherwise the party suffered no set- back. Rummel joined the Berger party and has once been elected a member of the State Senate. Later on when the Social Democratic party was formed, it found a warm supporter in Mr. Berger and his “independent” group of Socialists. Mr. Berger has always fought the Socialist Labor Party; he even went so far in his eagerness to denounce the Socialist Labor Party that John Most in his “Freiheit” used to reproduce some of the slanderous attacks which appeared in the “Vorwarts.” The newly-founded Social Democratic party was a great aid to Berger. He now got aid from outside to further his cause. The readers of The People are well acquainted with what has become of the Social Democratic Party of this State. We have for the last five or six years through the medium of our papers kept them posted on what was transpiring in their camp.

The Socialist Labor Party has never been as strong in the Cream City, in fact, all throughout the Badger State as it is and has been during the last few years. The section has since several years established headquarters at Lipp’s Hall, Third and Prairie streets. A long list of names could be cited of comrades who have been active in behalf of the revolutionary movement. Our own Richard Koeppel, at present editor of our national German organ, has, like so many others, made the movement what it is today–a healthy, pure but forceful stream, feared by its enemies, but loved and respected by those standing for a better system for a higher standard of civilization. This is the Socialist Labor Party.

New York Labor News Company was the publishing house of the Socialist Labor Party and their paper The People. The People was the official paper of the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP), established in New York City in 1891 as a weekly. The New York SLP, and The People, were dominated Daniel De Leon and his supporters, the dominant ideological leader of the SLP from the 1890s until the time of his death. The People became a daily in 1900. It’s first editor was the French socialist Lucien Sanial who was quickly replaced by De Leon who held the position until his death in 1914. Morris Hillquit and Henry Slobodin, future leaders of the Socialist Party of America were writers before their split from the SLP in 1899. For a while there were two SLPs and two Peoples, requiring a legal case to determine ownership. Eventual the anti-De Leonist produced what would become the New York Call and became the Social Democratic, later Socialist, Party. The De Leonist The People continued publishing until 2008.

PDF of issue 1: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/070518-weeklypeople-v17n08.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/070525-weeklypeople-v17n09.pdf